2 May 2019 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Serbia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106589″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Every Saturday, for the past five months, thousands of people have gathered on the streets of Serbian capital Belgrade to voice their dissent against President Aleksandar Vučić’s authoritarian tendencies and increasing control over the country’s media.

“Initially the protests were named ‘Stop the Bloody Shirts’,” Serbian journalist Lazara Marinkovic said. “And this was a reaction to an incident that happened in one city in Serbia, where Borko Stefanaović, an opposition leader, was physically beaten.”

Stefanaović, who was attacked last November in Kruševac, is the president of the political party Serbian Left and a founder of opposition coalition Alliance for Serbia. His assault, in which a masked group of assailants armed with bats and steel bars beat him, led to a rally in Belgrade.

“These people were saying that the beating happened as a result of political violence that the opposition is exposed to,” continued Marinkovic. “After one or two weeks, our president vucic had a reaction to those protests. He said ‘even if five million people were on the streets, (he) wouldn’t concede to their demands.’”

This sparked the formation of protests dubbed “one in five million” – a name lifted directly from Vučić’s comment. Though it remains uncertain whether the ongoing rallies will bring about change, Mitra Nazar, a Balkans correspondent for Dutch public broadcaster NOS, says it is “important” for protesters to demonstrate their unhappiness with Vučić.

“At this moment it’s about showing presence in the street more than actually having the feeling that they could change something,” said Nazar, who currently lives in Belgrade.

“I don’t think anybody in these protests believes that this could turn around now, but they do see this as part of a bigger movement that could eventually grow into something substantial, that could challenge the ruling party at elections.”

The demonstrations are the biggest since the fall of former President Slobodan Milosevic in 2000 – though lack of coverage in mainstream Serbian media would suggest otherwise. With Vučić pushing for Serbia to join the European Union, his grip on the media has tightened in efforts to appear stable to Brussels.

“Vučić wants to be the person that brings Serbia into the EU,” continued Nazar, “and in Brussels Vučić is still seen as a leader who can guarantee stability in the Balkans, and someone who’s willing to negotiate about a solution for the frozen conflict in Kosovo.

“His critics say the EU does not pressure Vučić enough on topics like media freedom, whilst they see his control over the media getting stronger.”

The country’s public broadcaster RTS has been targeted by demonstrators who are critical of the outlet’s coverage of the protests. The opposition says that, although reporting is completely neutral, it fails to ask why such a huge amount of people gather outside its headquarters in Belgrade every week.

“They are being biased,” added Marinkovic. “There was an incident when people who were demonstrating went inside the (RTS) building.

“They say that they didn’t go inside violently but some violence did happen because there was a lot of police who started kicking them out. Many people will agree that if these people do something violent, or vandalise something, it would be immediately used against them.

“They are trapped in a way they cannot really radicalise their protest. Nobody listens, nobody cares. It’s just like an echo chamber basically.”[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556799282299-4d20cd01-70c2-7″ taxonomies=”7370, 113″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Oct 2015 | Angola, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Portugal

It all became perfectly clear in Miguel’s head when a high-ranking editor from his newspaper eagerly approached him one day with a story idea. It was August 2012, and the Angolan presidential elections were scheduled for the 31st.

“You’re going to write an article that will prove once and for all to the Portuguese audience that Angola is a true democracy and not dictatorship. We’ll show that it is the Portuguese who are the fascists here, not the Angolan,” the editor told him.

The assignment came as no surprise to Miguel, who was aware of the rumours that the cash-strapped newspaper he works for is one of the many Portuguese media outlets that have received cash infusions funded by Angolan investors. These investments come from individuals connected to Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos, the man who enriched himself and his country’s tight-knit elite throughout his 36 years of power. While rich in resources — Angola figures among the world’s top producers of oil and diamonds — the country’s profits benefit very few. The most shocking example of that is the fact that this former Portuguese colony has the world’s highest mortality rate for infants and for children under the age of five.

Eventually, after informing his editor that he didn’t share the opinion that “Angola is a true democracy”, Miguel acquiesced and wrote the article on the condition that his byline would not appear.

Later that month, on 31 August 2012, dos Santos won the election with a controversial 71.84% of the votes.

“After that, I imposed on myself a kind of conscious negligence on everything relating to Angola. I stopped thinking about it, not just in order to keep my job, but also for mentality’s sake,” Miguel admits.

Ownership of Portuguese media outlets by Angolan oligarchs is a way for the dos Santos regime to hide the country’s negative side while promoting it before a foreign audience, experts say.

“They know better than anyone that the media can help them create the illusion that Angola is a good example when it comes to politics, the economy or even human rights,” says Portuguese MEP Ana Gomes, a member of the European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Human Rights and a close follower of the Angolan situation. “It grants good publicity and an idea of respectability to Angolan personalities who got all their money by stealing assets of the Angola state.”

Francisco Louçã, a former leader of the Portuguese Left Block political party and co-author of the book The Angolans Who Own Portugal, told Index on Censorship that “by owning strategic positions of the Portuguese media, these businessmen and businesswomen who are very close to the Angolan regime can manage and condition the information that reaches Portugal, which, from their perspective, is the perfect gateway for other European markets”.

It’s hard to find a media title in Portugal that isn’t owned in some way or another by Angolan oligarchs — and although Portugal has yet to see the effects of media transparency legislation that will make it mandatory for newspapers to reveal their shareholders beginning on 27 October, many news reports dating back to 2008 show that Angolan money is being invested in the Portuguese media.

In March 2014, António Mosquito, an Angolan businessman with close ties to the president, purchased a 27.5% stake in Controlinvest media group — including Diário de Notícias, the country’s oldest newspaper, and Jornal de Notícias, the second-most read. A few months after this deal, 160 workers were laid-off, including 64 journalists.

Then there’s Newshold, a media group owned by Angolan banker and businessman Álvaro Sobrinho. After buying the weekly Sol in 2008, Newshold announced the acquisition of the daily i in 2014. Newshold is also a shareholder in the two largest national media empires: 1.9% in Cofina, which includes Portugal’s highest circulation newspaper, Correio da Manhã; and 3.2% of Impresa, owner of television powerhouse SIC and the prestigious weekly Expresso.

In 2012, Newshold was also a frontrunner for the concession of RTP, the Portuguese public television network, after the government announced that it was willing to put it into the hands of private owners — a sale that was later dropped.

Then there is the case of Isabel do Santos, daughter of the Angolan president and Africa’s richest woman. Much of her $3.1 billion (£2.07 billion) net worth has been facilitated by her father’s decisions, which led to Forbes to dubbing her “daddy’s girl”. Not long after that piece was published, Isabel dos Santos bought the rights to produce a Portuguese-language version of Forbes which will be sold in Portugal and in Portuguese-speaking African countries.

Although Isabel dos Santos has no reported ownership of a Portuguese media outlet, she does co-own NOS, Portugal’s leading cable television company, in a joint-venture with the Portuguese telecom mogul Sonaecom — which is also the owner of the daily Público.

“Portugal is a vanity fair for the so-called Angolan elite,” says Angolan investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais, winner of the 2015 Index Journalism award for his work uncovering corruption in his country.

Whether they are the recipients of direct investments or not, all newspapers in Portugal are dependent on money from Angola’s elite in the form of advertising. With holdings in Portugal’s real estate, telecoms, construction and banking industries, Angolan investors can potentially influence coverage through contracts for ad space.

It isn’t always clear how the Angolan money is invested in Portugal’s media. For example, in the case of i, a newspaper that has struggled with financial issues, a February 2012 purchase of a 70% stake by printing-house owner Manuel Cruz was completed behind a reluctance to reveal the identity of the investors. “It’s a deal that is done through a foreign group, of which I’m a shareholder representative in Portugal,” Cruz was quoted as saying at the time.

However, inside the newsroom, journalists became alert to the possibility that that investment had roots in the Angolan oligarchy. “It became known through rumours, which were later proved to be true,” says António Rodrigues, a former editor of i’s foreign news desk. “It got pretty obvious even without an official confirmation. It’s impossible for the owner of a printing house to be able to afford to suddenly buy an unprofitable newspaper during an economic crisis. There had to be someone from Angola behind him.”

Rodrigues was right. But this was only to be fully brought to light in September 2014 when i and Sol moved into the same building.

In the meantime, while journalists were left to speculate on who their mysterious bosses were, news regarding Angola became a sensitive topic. “One had to be more careful and it was policy to ask the editors-in-chief for permission to publish anything related to Angola,” Rodrigues said.

After seven months working under the new owners, Rodrigues was laid off and the foreign news section was left without a permanent editor — such responsibilities were transferred to the masthead. This led to a gradual, yet steady loss of importance of the foreign news section in the paper. It didn’t take long until negative news concerning Angola nearly disappeared from i, Rodrigues said.

Other Portuguese news outlets appear to have limited their coverage of Angola. The ongoing hunger strike by Luaty Beirão — an Angolan-Portuguese rapper who began protesting on 21 September after being accused, along with 14 other activists, of preparing “crimes against [Angola’s] state security” — has been met with reluctance by some newspapers. i and Jornal de Notícias are yet to give more space to the subject than a brief item. And while it did write about new business opportunities for Isabel dos Santos, Diário de Notícias devoted only a little more than one column to the hunger strike when a demonstration for Beirão’s freedom took place in Lisbon to mark the 25th day of his protest.

On 27 October, Portugal will implement a media transparency law that will make it mandatory for newspapers to divulge their list of shareholders — TV and radio stations already follow this procedure. Until recently, similar drafts have been voted down by the centre-right governing coalition.

“Resistance by the media owners to laws of this kind is very high and some parties respect this clearly. The Angola regime is a sacred cow to some of them,” says Louçã.

“Finally we have such a law that will bring some light to this very dark issue. And I’m sure that if we follow the money trail, we’ll always find our way to very important personalities of the Angolan regime with high stakes in the Portuguese economy,” says Gomes.

However, Marques de Morais, a connoisseur of the ways of the Angolan oligarchy, is more skeptical of the results of this new law.

“If the regime of José Eduardo dos Santos has shown an ability to do something, it’s to hide their footsteps. There is always a way for them.”

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 21 October 2015

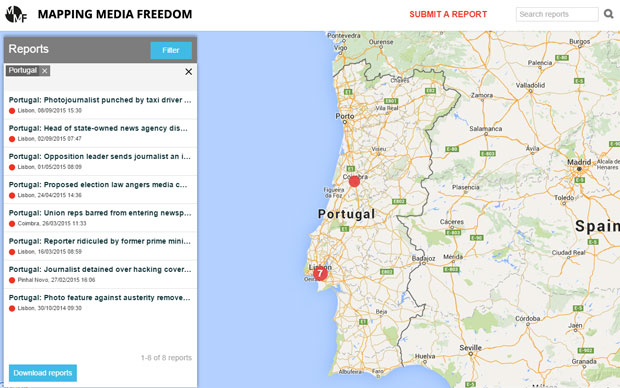

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|