25 Oct 2024 | Ireland, News and features

Following a two-day mission to Dublin on 22-23 October 2024, the partners of the Council of Europe’s Platform on Safety of Journalists today called on Irish authorities to continue to engage with civil society in order to prioritise the reform of defamation legislation, the adoption of comprehensive anti-SLAPP provisions, the safety of journalists throughout the island of Ireland, and a sustainable model for trusted public service media.

The Partner organisations met with journalists, representatives of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) and government officials from the Department of Justice and the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media. The delegation noted with concern the ongoing delays in reforming Ireland’s defamation laws and highlighted the urgency of reform that incorporates strong anti-SLAPP provisions. The organisations also note the transposition timeline for the EU Anti-SLAPP Directive requires a timely engagement by the authorities on this vital issue.

While it is unlikely the Defamation (Reform) Bill will be passed prior to the expected General Election, it is vital the new administration gives priority to this Bill.

Without the necessary reforms, Ireland will be without adequate protections against abusive legal threats at a time when powerful actors, including politicians, are using defamation and the threat of defamation law to silence or intimidate journalists.

We further express our grave concern regarding the treatment of journalists and their sources in Northern Ireland, exemplified by but not limited to the cases of Barry McCaffrey and Trevor Birney who have been surveilled by police forces based in England and Northern Ireland to identify their sources. Evidence produced during hearings of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal has established that McCaffrey’s communications have been monitored on five separate occasions between 2008 and 2018. There have been further reports of applications to access the information of more than 320 journalists and 500 lawyers. Due to the cross-border nature of this alleged surveillance and journalism, we call on the Irish authorities to engage with its UK counterparts to ensure that such flagrant abuses of press freedom are prevented in the future.

The delegation recognises and welcomes the efforts of the Irish authorities to maintain a structural dialogue with journalists themselves, through the presence of NUJ and journalist representatives on the Media Engagement Group. Such engagement is vital at times of heightened tensions, such as demonstrations, elections and protests and is at the heart of the Council of Europe Journalism Matters campaign. We urge the next administration to maintain this work and to ensure it is resourced sufficiently in order to remain a vital and valued resource and point of support for all journalists. This could ensure Ireland can become an exemplar for other Council of Europe member states in respect of promoting the safety of journalists.

The Platform is concerned by reports of the Garda Síochána demanding access to journalists’ material particularly related to covering demonstrations. We call on the Gardaí to cease making these demands which also increase the security risks faced by journalists who may be targeted by demonstrators who believe their recordings will be used by the Gardaí. Moreover we call on the Gardaí to do more to engage with journalists on protecting them from growing threats online or offline.

The Platform partners are also concerned by the recently announced 3-year funding model for the Irish public broadcaster RTÉ, which risks resulting in staff cuts and the outsourcing of productions. We call on the authorities to ambitiously implement the European Media Freedom Act’s Article 5, which obliges EU Member States to ensure adequate, sustainable and predictable funding for public service media.

Finally, the delegation calls on the Irish government to take fresh action in respect of the 2001 murder of journalist Martin O’Hagan. A new government in the UK and an imminent election in Ireland provides the opportunity for a fresh start in this case to ensure impunity does not endure. We call on the Irish government to engage with the UK authorities to take effective actions in order to investigate this egregious case anew.

The delegation was composed of representatives from the Association of European Journalists (AEJ), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF), the European and International Federations of Journalists (EFJ-IFJ), Index on Censorship, the International Press Institute (IPI), Justice For Journalists Foundation (JFJ), PEN International, International News Safety Institute (INSI) and Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

10 Nov 2022 | FEATURED: Martin Bright, News and features

Imagine a country where the authorities target investigative journalists as spies, and outlaw news and campaigning organisations that receive foreign funding. At Index on Censorship, we have been writing about such countries since the darkest days of the Cold War.

Now, a coalition of organisations promoting free expression and the rights of journalists is raising serious concerns about sweeping measures contained in new legislation here in the UK.

openDemocracy – alongside the National Union of Journalists, Reporters Without Borders and Index on Censorship itself – has asked for an urgent meeting with security minister Tom Tugendhat to discuss our joint submission to the parliamentary committee scrutinising the new National Security Bill. (The bill is currently at report stage in the House of Commons, due to go to the House of Lords next.)

An unusual bout of consensus appears to have broken out in Westminster over this particular piece of new legislation. In part, this is due to the British government’s tactical retreat from a full-scale overhaul of the 1989 Official Secrets Act – which would have caused concern for libertarians on the government benches.

The importance of national security in a time of global instability is something we can all understand. And a toughening of measures to crack down on bad foreign actors is relatively easy to sell.

But it is wise to be vigilant when parliamentary consensus occurs – especially when citizens are being asked to trade personal freedoms in exchange for promises of greater security. Civil liberties risk being squeezed between a government desperate to show its toughness in the face of presidents Putin and Xi and an opposition keen to burnish its security credentials.

The new legislation is designed to address serious new threats that have only emerged since the start of the 21st century. There is no question that the growth of the internet has posed challenges to UK security. This, combined with the direct hostility of Russia and the growing geopolitical significance of China, has led to concern in Whitehall about the suitability of existing legislation.

The Home Office claims that the new bill “completely overhauls and updates our outdated espionage laws” – a bold assertion. It also promises a “range of new and modernised offences, with updated investigative powers and capabilities”. These, it says, will “ensure those on the front line of our defence will be able to do even more to counter state threats”.

Such language is designed to instil maximum reassurance in the face of a terrifying and unspecified threat from a hostile foreign government.

But where are the limits to such legislation?

Public interest defence

Our coalition has identified several areas of concern, but chief among them is the chilling effect the new legislation will have on the practice of investigative journalism. The absence of meaningful free-expression protections means that whistleblowers in government will be further deterred from disclosing official wrongdoing.

The new legislation makes it clear that those in receipt of information or documents deemed to benefit foreign powers will face the most severe penalties – up to a maximum of life imprisonment. Although ministers gave assurances under questioning that these measures are not designed to target journalists, such protections are not written into the legislation. The decision to prosecute would ultimately lie with the attorney general of the day.

In the face of such sweeping measures, we are demanding the introduction of a public interest defence to increase protections for those exposing genuine wrongdoing in the sphere of national security.

Fundamental to the concerns of our coalition are the so-called “foreign power conditions” woven throughout the new legislation. Our fear is that the measures are so broadly drawn that journalists and free-speech organisations could be swept up in a future crackdown.

The scope of the National Security Bill as presently drafted is so vast that any organisation receiving foreign funding – including foreign news services – could be caught up by it.

Democracy depends on vibrant and critical journalism. The UK government should resist the desire to sacrifice media freedom on the altar of national security.

This piece first appeared on OpenDemocracy.

4 May 2017 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

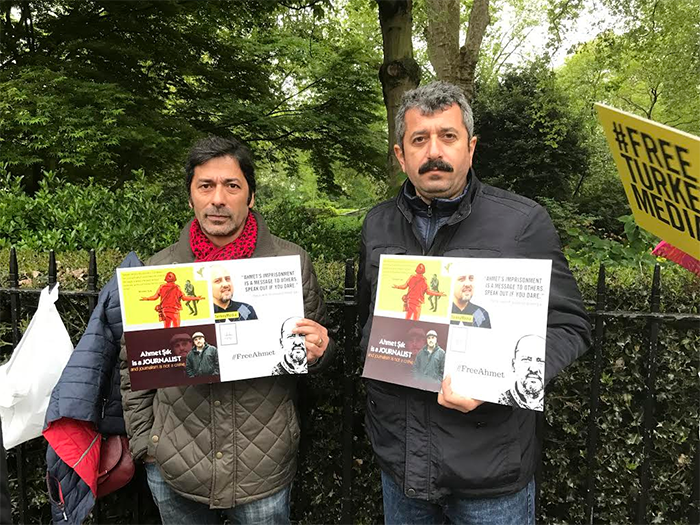

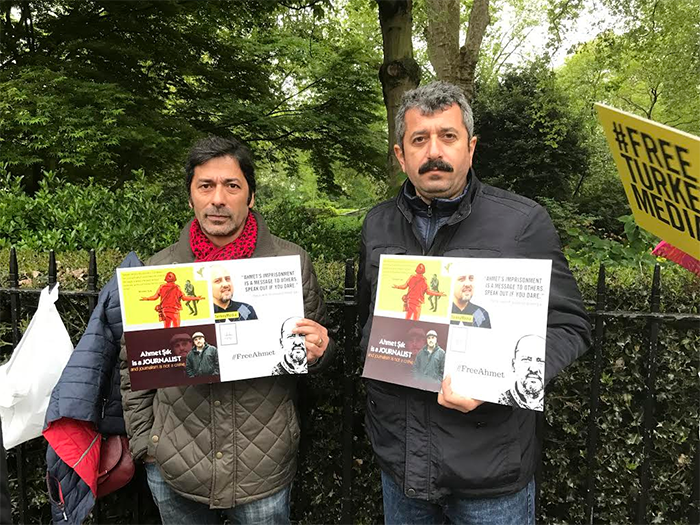

On 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, dozens of activists and journalists gathered outside the Turkish Embassy in London to protest the arrest and imprisonment of journalists in Turkey. Index on Censorship joined Amnesty International, English Pen, Article 19 and others bearing signs and messages of hope.

Following the failed military coup in July of 2016, the Turkish government has unleashed a massive crackdown on its opposition, specifically targeting journalists, media outlets and educators.

Since then, over 150 journalists have been detained and over 170 media outlets have been shut down, resulting in an additional 2,500 journalists being out of work. Turkey is now the number one jailer of journalists in the world.

Seamus Dooley, the acting general secretary of the Nation Union of Journalists, addressed the protest, which took place across the street from the embassy: “We may be on the wrong side of the road but we are on the right side of history.”

Dooley highlighted the importance of coming out to protest in support of Turkey’s journalists, regardless of the weather: “Solidarity is the most important thing we can give them. Although this may seem like a dark time, the fact we are still with them shines a light on it.”

Many protesters stressed the importance of continuing to campaign until those being silenced in Turkey are free.

Ulrike Schmidt, Amnesty International

Ulrike Schmidt of Amnesty International said: “As a human rights organisation it’s our job to speak out. It’s World Press Freedom Day so we’re standing here to support the journalists in Turkey. We will keep campaigning until they can do their work again.”

Others spoke out specifically about friends who had been detained as a result of the crackdown. Two of the protesters (pictured below) came specifically to highlight the case of Ahmet Sik, a journalist with the Turkish opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet, who is currently being tried on accusations of spreading terrorist propaganda as well as insulting the state.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493899892143-33f1af52-13d4-5″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Nov 2012 | Uncategorized

Lord Justice Leveson has been dealt a bad hand. On Thursday he’ll fulfil his task of recommending a new regulatory system for the British press — that vague bunch whose boundaries and levels of entry shift with each technological innovation.

It’s possible Sir Brian’s report will have a brief life in the age of the internet: A world where we are all publishers, where citizen journalists and reporters on national papers curate and cover the same stories, where traditional models of journalism are chipped away. But Leveson is determined to recommend something that works for the public, the public who were disgusted (rightly so) at the phone hacking scandal.

So what’s on the table? The industry and the newly-formed Free Speech Network is flying the flag for improved self-regulation. Index has called for a model of tough, independent regulation free from government interference. Campaign group Hacked Off is pushing for statutory underpinning of a new independent regulator, a model the National Union of Journalists and several Tory MPs and peers defended earlier this month.

Hacked Off and its camp argue that only a dab of statute is needed for the press to get its house in order and serve the public. A new regulator would be created by parliamentary statute, but would not play a role in day-to-day operations, sitting instead at arm’s length from Westminster.

But would statute even keep up with the pace of change in the digital age? Would we see statutory definitions of privacy and the public interest as well?

Either this country has a press entirely free from government interference, or it doesn’t, quoting the Spectator’s Fraser Nelson. A new regulator might not play a part in daily operations, but, as Nelson writes, “as soon as the device of political control is created, it can be ratcheted up later.”

It is now our country’s journalists who risk paying the price for the actions not only of a few reporters but also of power-seeking politicians and police. Ordinary journalists who are, let’s not forget, already hemmed in by England’s chilling libel laws and the plethora of other criminal legislation, several areas of which do not carry a public interest defence for reporters.

And, to muddy the waters a little more, we are all journalists now, to use author Nick Cohen’s words. That’s why the hand Leveson’s been dealt is a tough one: his recommendations may not just affect the press, they could affect all of us who blog, tweet our views or share our sentiments on Facebook.

Those of us who obsess about press freedom might well have concerns about bringing statute into the game. And why shouldn’t we? Hard-won freedoms that are chipped away at, however well-intentioned, can be hard to replace.

Marta Cooper is an editorial researcher at Index on Censorship. She tweets at @martaruco

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]