2 Feb 2018 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Protesters against the KCK press trial marched in Istanbul in January 2012. (Photo: DIHA News Agency)

Turkey can hardly claim a glorious history in terms of press freedom. But even by the standards of the country’s turbulent political past, the soaring number of trials, detentions and convictions of journalists are setting a terrifying precedent.

In 2012 a monumental case dubbed the “KCK press trial” made the headlines as the country’s biggest media trial: 46 journalists, 36 of whom remained in custody for between a few months and two-and-a-half years, were accused of being link to the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK), a semi-clandestine organisation that was alleged to be the “urban wing” of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). Six years after it began, and with all the suspects released during successive hearings, the trial continues to drag on at a lethargic pace. The latest hearing held on 19 January 2018 hardly made the news.

However, the seeming inertia shouldn’t be interpreted as a good omen. A lawyer representing the accused journalists stressed that the KCK press trial was the model for the many trials opened against journalists and news outlets in the wake of the failed July 2016 coup. “We weren’t surprised when we read the indictment against the Cumhuriyet newspaper,” lawyer Özcan Kılıç told Mapping Media Freedom, referring to the ongoing media trial that has drawn the most public attention. “Those are the exact same allegations that were levelled against those in the KCK press trial. In fact, the KCK press trial is used as a template against all unwanted organisations. Yesterday it was the Kurds, now it’s social democrats. Tomorrow? Who knows?”

Reports on abuse of child convicts used as evidence

The journalists on trial in the KCK case all worked for pro-Kurdish news outlets, including Dicle News Agency (DİHA), as well as the dailies Özgür Gündem and Azadiya Welat, all of which were shuttered by decree following the declaration of a state of emergency in July 2016. Because the prosecution failed to pin any concrete evidence on the accused journalists, their routine professional work was exploited to substantiate the charges.

“The trial didn’t contain any legal allegations, but from the government’s perspective, it was an operation that brought up political allegations,” said Çağdaş Kaplan, a former reporter for DİHA who was among the journalists remanded in detention pending trial. “If you looked at the evidence in the indictment, a great majority of the allegations against journalists were based on news reports, articles or interviews that had their bylines in their outlets, or were based on the communications they had with their sources,” Kaplan, who now works for the online news website Gazete Karınca, told Mapping Media Freedom.

Evrim Kepenek, another former DİHA reporter, joined Kaplan in stressing that the KCK press trial represents a grim milestone in the use of journalistic work as criminal evidence. “None of us denied that we worked at that agency or covered those news stories. Our news agency paid taxes, distributed press cards, registered with social security and had reporters who would be free to join the Turkish Journalists’ Union,” she said.

The evidence against the journalists included news reports unrelated to the KCK trials or even inoffensive articles. In a notorious twist, the coverage of a child abuse case at the Pozantı Juvenile Detention Centre was included in the indictment, which accused the journalists of reporting stories that could “damage the image of the state” and “humiliate the Turkish state in the eyes of the public”. The lead reporter on the story, Özlem Ağuş, remained in custody for two years because of her work.

Water sleeps, but the state never rests

The investigations launched into journalists were part of a wider crackdown on Kurdish politicians and political activists that began in 2009. There were two other mass trials ongoing: 205 Kurdish politicians are on trial in Istanbul, while another 175 defendants are being tried by a Diyarbakır court.

On 20 December 2011 police launched operations on the Istanbul offices of many pro-Kurdish outlets, detaining 49 people and seizing news material. Some 36 journalists were arrested after four days of interrogation on 24 December. Some 44 journalists were initially charged before two colleagues were added to the list.

Kılıç, the lawyer, said they referred to the concept of “Enemy Criminal Law” to refer to the legal cases. “It’s a reflection of the mind of the state. This is how it works: You identify your enemy and you make a terrorist out of them,” he said.

Kılıç, who also represents the Diyarbakır-based Özgür Gündem, the most influential Kurdish newspaper published in Turkey until it was shuttered by an emergency decree in August 2016, said the ongoing cases against the daily demonstrated the same mentality. Referring to a case in which the newspaper’s former editor-in-chief, İnan Kızılkaya, and intellectuals who showed solidarity with the outlet, such as acclaimed author Aslı Erdoğan and writer Necmiye Alpay, face aggravated life sentences, Kılıç said: “The exact same template as the KCK press trial was used. Water sleeps, but the state never rests.”

Lawyers are now awaiting a decision from the European Court of Human Rights, which is expected to weigh in on whether the journalists’ freedom of expression was violated. A decision in favour of the journalists could ensure they are not convicted in a Turkish court, according to the lawyers.

Police chief and judge imprisoned

However, the legal system itself has experienced seismic changes in recent years. First, the Turkish government abolished the specially authorised heavy penal courts in March 2014 as part of a “peace process” with the Kurdish political movement. The court overseeing the KCK press trial was one of them. However, the constitutional court rejected demands for a retrial by defence lawyers, even though the court agreed to rehear other important cases, such as the Ergenekon military coup case.

To rub salt into the wound, the police chief who ordered the arrests of the Kurdish journalists and the lead judge overseeing their case were subsequently accused of being members of the Gülen movement. Once a close ally of the ruling Justice and Development Party, the movement led by US-based Islamist cleric Fethullah Gülen was accused of staging several plots to overthrow the government, including the July 15, 2016, coup attempt. The movement has since been declared a terrorist organisation called “FETÖ”.

The police chief, Yurt Atayün, has been in custody since the government began purging suspected Gülenists from within the state in 2014, while the head judge, Ali Alçık, was arrested a few days after the coup attempt.

But while the government quickly moved to overturn other trials that were allegedly fabricated by the Gülen movement, it has not done so in the KCK press trial.

“The trial should have already been dismissed because ordinary news reports and phone conversations – the kind that every reporter makes – were presented as evidence. On top of it, those who smeared us were found to be FETÖ members. It should have been dismissed without further ado, but it hasn’t been yet,” Kepenek said.

‘Current situation much more severe’

Even if the trial continues despite the seeming collapse of the prosecution’s case, that doesn’t mean the journalists will ultimately be acquitted, Kaplan said, noting that the Turkish government defended itself to the European Court of Human Rights by continuing to insist that the journalists were “terrorists”. “Even though the defendants are journalists, this doesn’t mean that they are not terrorists,” Turkey stated.

“The trial is not continuing as a formality but as a way to threaten. We are continuing to do our job but face several years in prison,” Kaplan said.

For her part, Kepenek expresses concern that the situation today is becoming inexorably worse. Kepenek, a reporter for the pro-Kurdish and feminist Jinnews online news outlet, notes that access to their website was blocked five times in just one week in late January. Journalist Zehra Doğan, the founder of Jinnews and the winner of the 2017 Freedom of Thought Award from the Swiss-based Freethinkers organisation, is also in jail for paintings that portrayed the Turkish army’s crackdown on Kurdish provinces in late 2014 and early 2015.

“We are experiencing a much more severe process,” Kepenek said. “The allegations in the KCK press trial may have collapsed, but now they don’t even need to present allegations. It was possible to sentence my friend Nedim Türfent to over eight years in prison for reporting on the conflict in Hakkâri. What they call proof is news stories. In other words, our reporting is way beyond the process of being declared a crime: It has legally become a ‘crime.’”

In March 2012, less than two months after an operation against Kurdish media outlets, the then-prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, said those arrested were “terrorists, not journalists” for not carrying the prime minister’s “yellow press card”. Now, six years later, he repeated the exact same words during a joint press conference last month with French president Emmanuel Macron in Paris. Yet in the meantime, journalists whom he described as “terrorists” have been freed while those who prosecuted them are now imprisoned on terror charges.

The KCK press trial may be a showcase example that allegations won’t stand the test of time even if politicians’ tactics remain the same – even as the journalists stressed the importance of solidarity.

“Those who remained silent back then are getting their share of the pressure today. This is why we should understand that both the pressure against the Kurdish media in 2011 and the pressure under the state of emergency are attacks against journalism,” Kaplan said.

If anything, the pressure has even emboldened many journalists, Kepenek added. “Journalists’ pens don’t break when they arrest them; they sharpen even more. Governments fail to understand that.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

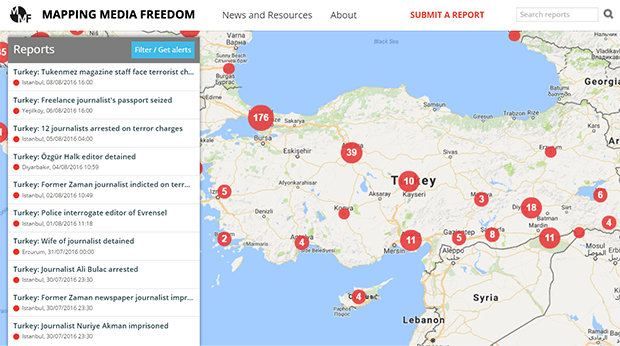

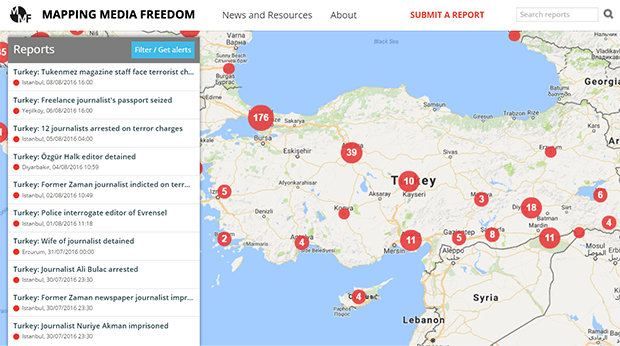

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,850 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1517575508678-6c92400a-510e-8″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Award-winning writer, human rights activist and columnist Aslı Erdoğan

“When I understood that I was to be detained by a directive given from the top, my fear vanished,” novelist and journalist Aslı Erdoğan, who has been detained since 16 August, told the daily Cumhuriyet through her lawyer. “At that very moment, I realised that I had committed no crime.”

While her state of mind may have improved, her physical well-being is in jeopardy. A diabetic, she also suffers from asthama and chronic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“I have not been given my medication in the past five days,” Erdoğan, who is being held in solitary confinement, added on 24 August. “I have a special diet but I can only eat yogurt here. I have not been outside of my cell. They are trying to leave permanent damage on my body. If I did not resist, I could not put up with these conditions.”

An internationally known novelist, columnist and member of the advisory board of the now shuttered pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem daily Erdoğan was accused membership of a terrorist organisation, as well as spreading terrorist propaganda and incitement to violence.

According to the Platform for Independent Journalism, Erdoğan is one of at least 100 journalists held in Turkish prisons. This number – which will rise further – makes Turkey the top jailer of journalists in the world.

Each day brings new drama. Erdoğan’s case is just one of the many recent examples of the suffering inflicted on Turkey. It is clear that the botched coup on 15 July did not lead to a new dawn, despite the rhetoric on “democracy’s victory”.

Turkey faces the same question it did before the 15 July: What will become of our beloved country? Like the phrase “feast of democracy” – which has been adopted by the pro-AKP media mouthpieces – it has been repeated so often that it habecome empty rhetoric.

Such false cries only serve the ruling AKP’s interests. Even abroad there are increased calls that we should support the government despite the directionless politics in Turkey and the state of emergency.

In a recent article for Project Syndicate entitled Taking Turkey Seriously, former Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt wrote: “The West’s attitude toward Turkey matters. Western diplomats should escalate engagement with Turkey to ensure an outcome that reflects democratic values and is favorable to Western and Turkish interests alike.”

Lale Kemal took Turkey seriously. As one of the country’s top expert journalists on military-civilian relations, Kemal stood up for the truth, barely making a living as no mogul-owned media outlet would publish her honest journalism. She headed the Ankara bureau of independent daily Taraf, now shut down because of the emergency decree. She now sits in jail for the absurd accusation that she “aided and abetted” the Gülen movement, an Islamic religious and social movement led by US-based Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan refers to the movement as the Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation (FETO) and blames it for orchestrating the failed coup.

But actually, Kemal’s only “crime” was to write for the “wrong” newspapers, Taraf and Today’s Zaman.

Şahin Alpay also took Turkey seriously. As a scholar and political analyst he was a shining light in many democratic projects and one of the leading liberal voices in Turkey.

Three weeks ago, he was detained indefinitely following a police raid at his home. His crime? Aiding and abetting terror, instigating the coup and writing for the Zaman and Today’s Zaman. This last point is now reason enough to deny such a prominent intellectual his freedom.

Access to the digital archives of “dangerous” newspapers – Zaman, Taraf, Nokta etc – is now blocked. This is a systematic deleting of their entire institutional memory. All those news stories, op-ed articles and news analysis pieces are now completely gone.

Basın-İş, a Turkish journalists’ union, stated that 2,308 journalists have lost their jobs since 15 July, and most will probably never to be employed again. Unemployment was their reward for taking Turkey seriously.

Erdoğan, Kemal and Alpay, like many journalists, academics and artists who care for their country, are scapegoats for the erratic policies of those in power.

Even businessmen have fallen victim to the massive witch hunt against “FETO”. Vast amounts of assets belonging to those accused of being Gülen sympathisers have been seized and expropriated by the state. Not long ago these businessmen were hailed as “Anatolian Tigers”, who opened the Turkish market to globalisation.

The seizures will probably draw complaints at the European Court level. They are sadly reminiscent of the expropriations at the end of the Ottoman Empire, which had targeted mainly Christian-owned assets.

What all of these cases have in common isn’t the acrimony that pollute daily politics in Turkey. It is the total sense of loss for the rule of law, made worse by post-coup developments.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

19 Aug 2016 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia, Serbia, Turkey

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

16 August, 2016 – IMC TV reporter Gulfem Karatas and cameraman Gokhan Cetin were assaulted and detained while covering the police raid on the daily Ozgur Gundem. Footage of the attack was shared via IMC TV Twitter account, showing police grabbing the camera and physically assaulting the reporter, who is heard screaming in the footage.

Karatas and Cetin were detained along with journalists Günay Aslan, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Ender Öndeş, Doğan Güzel, Ersin Çaksu, Kemal Bozkurt, Sinan Balık, Önder Elaldı, Davut Uçar, Zana Kaya, Fırat Yeşilçınar and Mesut Karnak.

In an official statement IMC TV said: “During the live broadcast, the police prevented Gulfem Karatas and Gokhan Cetin from reporting and detained them violently along with at least 21 Ozgur Gundem employees. We condemn this unacceptable treatment to our colleagues who were on duty and ask for their immediate release.”

16 August, 2016 – Journalist Vladimir Zivanovic and photographer Boris Mirko, who work for the daily Serbian Telegraph were threatened and insulted while reporting on the illegal construction of an aqua park in the capital Belgrade.

The journalists were in an area of the city where former professional football player Nikola Mijailovic is building the controversial aqua park. Mijailovic approached the journalists and shouted a series of insults about them and their families. He reportedly told them that they should be put in a gas chamber together.

Mijailovic also reportedly tried to bribe them. The journalists have reported the threats to the police and Serbia’s Independent Association of Journalists has condemned the incident.

15 August, 2016 – A court in Baku ruled to uphold a travel ban against investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova. “Binagadi Court told me because I have no husband, kids or property, I might not be able to return if I leave the country,” Ismayilova said following the hearing in Baku.

Ismayilova was released from prison on 25 May on a suspended three-and-a-half-year sentence.

Also read: Azerbaijan’s long assault on media freedom

16 August, 2016 – The eighth administrative court in Istanbul ordered the closure of the newspaper Ozgur Gundem on the grounds of “producing terrorist propaganda”.

The court order described the closure as “temporary” although no duration appears to be specified in the text of the decision.

Later that day, Ozgur Gundem’s offices were raided by the police.

According to P24, the 23 members of staff were taken into custody. They are: Editor-in-Chief Zana Kaya, journalists Zana Kaya, Günay Aksoy, Kemal Bozkurt, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Önder Elaldı, Ender Önder, Sinan Balık, Fırat Yeşilçınar, İnan Kızılkaya, Özgür Paksoy (DİHA news agency) , Zeki Erden, Elif Aydoğmuş, Bilir Kaya, Ersin Çaksu, Mesut Kaynar (DİHA), Sevdiye Gürbüz, Amine Demirkıran, Baryram Balcı, Burcu Özkaya, Yılmaz Bozkurt (member of the press office of the Istanbu Medical Chamber), Gülfem Karataş (İMC), Gökhan Çetin (İMC) and Hüseyin Gündüz (Doğu Publishing House).

Also read: Turkey’s continuing crackdown on the press must end

11 August, 2016 – Dmitri Remisov, the Rostov-on-Don regional correspondent for Rosbalt news agency, told the agency that he was repeatedly assaulted by police officers while being questioned at the regional Center for Counteracting Extremism.

According to Remisov, he was asked to come to the CCE to answer questions related to a criminal case “on the preparation of a terrorist act” in Rostov, a city in south-west Russia.

He reported that two police officers asked him whether he knew certain individuals, where most of the people he was asked about were opposition activists.

“Then they asked me if I knew a certain Smyshlayev. I said that I didn’t remember such a person,” Remizov said.“One officer started saying I did know this person in 2009, after which he struck my head three times. Afterwards, he began threatening me, saying he could prosecute me under the criminal law or could have some Nazis punish me.”

After he was questioned another policeman threatened him with physical punishment, saying “we will meet [with you] once again”.

The Rosbalt correspondent received medical care after the questioning. He also filed a complaint against police officers, Rosbalt reported.

11 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The number of threats to media freedom in Turkey have surged since the failed coup on 15 July.

One of the most vital duties of a journalist — in any democracy — is to report on the day-to-day operations of a country’s parliament. Journalism schools devote much time to teaching the deciphering budgets and legal language, and how to report fairly on political divides and debates.

I recalled these studies when I read an email Wednesday morning from an Ankara-based colleague. I smiled bitterly. The message included a link to an article published in the Gazete Duvar, which informed that 200 journalists had been barred from entering the home of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Security controls at the two entrances of the failed-coup-damaged building had been intensified and journalists were checked against a list as they tried to enter.

The reason for the bans? Most of those who were blocked worked for shuttered or seized outlets alleged to be affiliated with the Gülenist movement.

Parliament, though severely damaged by bombing during the night of the coup attempt, is still open. For any professional colleague, these sanctions mean only one thing: journalism is now at the absolute mercy of the authorities who will define its limits and content.

Many pro-government journalists do not think the increasingly severe controls are alarming. “It is democracy that matters,” they argue on the social media. “Only the accomplices of the putschists in the media will be affected, not the rest.”

If only that were true. Reality proves the opposite. Along with the closures of more than 100 media outlets, a wide-scale clampdown on Kurdish and leftist media is underway. Outlets deemed too critical of government policies have come under post-coup pressure.

Late Tuesday, pro-Kurdish IMC TV reported that the official twitter accounts of three major pro-Kurdish news sources — the daily newspaper Özgür Gündem and news agencies DIHA and ANF — were banned. Some Kurdish colleagues interpret the sanctions as part of an upcoming security operation in the southeastern provinces of Diyarbakır and Şırnak.

What I see is a new pattern: in the past three-to-four days, many Twitter accounts of critical outlets and individual journalists have been silenced. An “agreement” appears to have been reached between Ankara and Twitter, but no explanation has yet been given.

For days now, many people have been kept wondering about the case of Hacer Korucu. Her husband, Bülent Korucu, former chief editor of weekly Aksiyon and daily Yarına Bakış, is sought by police after an arrest order issued on him about “aiding and abetting terror organisation”, among other accusations. She was arrested nine days ago as police had told the family that “she would be kept until the husband shows up”.

The Platform for Independent Journalism provided more insight on Hacer Korucu’s detention and subsequent arrest. The motive? She had taken part in the activities of the schools affiliated with Gülen Movement and attended the Turkish Language Olympiade.

Hacer Korucu’s case, without a doubt, shows how arbitrary law enforcement has become in Turkey. As a result no citizen can feel safe any longer.

“She is a mother of five,” was the outcry of Rebecca Harms, German MEP. “A crime to be married to a journalist?”

How do we now expect an honest Turkish or Kurdish journalist to answer this question? By any measure of decency, the snapshot of Turkey in the post-putsch days leaves little suspicion: emergency rule gives a free reign to authorities who feel empowered to block journalists from covering the epicenter of any democratic activity — parliament — and let relatives of journalists suffer.

Meanwhile, we are told on a daily basis that democracy was saved from catastrophe on that dreadful July evening and it needs to be cherished.

But, like this? How?

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s

Each week, Index on Censorship’s