4 Dec 2017 | About Index, History, Magazine, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The first editor of Index on Censorship magazine reflects on the driving forces behind its founding in 1972″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]A version of this article first appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in December 1981. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The first issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, 1972

Starting a magazine is as haphazard and uncertain a business as starting a book-who knows what combination of external events and subjective ideas has triggered the mind to move in a particular direction? And who knows, when starting, whether the thing will work or not and what relation the finished object will bear to one’s initial concept? That, at least, was my experience with Index, which seemed almost to invent itself at the time and was certainly not ‘planned’ in any rational way. Yet looking back, it is easy enough to trace the various influences that brought it into existence.

It all began in January 1968 when Pavel Litvinov, grandson of the former Soviet Foreign Minister, Maxim Litvinov, and his Englis wife, Ivy, and Larisa Bogoraz, the former wife of the writer, Yuli Daniel, addressed an appeal to world public opinion to condemn the rigged trial of two young writers and their typists on charges of ‘anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda’ (one of the writers, Alexander Ginzburg, was released from the camps in 1979 and now lives in Paris: the other, Yuri Galanskov, died in a camp in 1972). The appeal was published in The Times on 13 January 1968 and evoked an answering telegram of support and sympathy from sixteen English and American luminaries, including W H Auden, A J Ayer, Maurice Bowra, Julian Huxley, Mary McCarthy, Bertrand Russell and Igor Stravinsky.

The telegram had been organised and dispatched by Stephen Spender and was answered, after taking eight months to reach its addressees, by a further letter from Litvinov, who said in part: ‘You write that you are ready to help us “by any method open to you”. We immediately accepted this not as a purely rhetorical phrase, but as a genuine wish to help….’ And went on to indicate the kind oh help he had in mind:

My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR. This committee could be composed of universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities from England, the United States, France, Germany and other western countries, and also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, in the future, even from Eastern Europe…. Of course, this committee should not have an anti-communist or anti-Soviet character. It would even be good if it contained people persecuted in their own countries for pro-communist or independent views…. The point is not that this or that ideology is not correct, but that it must not use force to demonstrate its correctness.

Stephen Spender took up this idea first with Stuart Hampshire (the Oxford philosopher), a co-signatory of the telegram, and with David Astor (then editor of the Observer), who joined them in setting up a committee along the lines suggested by Litvinov (among its other members were Louis Blom-Cooper, Edward Crankshaw, Lord Gardiner, Elizabeth Longford and Sir Roland Penrose, and its patrons included Dame Peggy Ashcroft, Sir Peter Medawar, Henry Moore, Iris Murdoch, Sir Michael Tippett and Angus Wilson). It was not, admittedly, as international as Litvinov had suggested, but it was thought more practical to begin locally, so to speak, and to see whether or not there was something in it before expanding further. Nevertheless, the chosen name for the new organisation, Writers and Scholars International, was an earnest of its intentions, while its deliberate echo of Amnesty International (then relatively modest in size) indicated a feeling that not only literature but also human rights would be at issue.

By now it was 1971 and in the spring of that year the committee advertised for a director, held a series of interviews and offered me the job. There was no programme, other than Litvinov’s letter, there were no premises or staff, and there was very little money, but there were high hopes and enthusiasm.

It was at this point that some of the subjective factors I mentioned earlier began to come into play. Litvinov’s letter had indicated two possible forms of action. One was the launching of protests to ‘support and defend’ people who were being persecuted for their civic and literary activities in the USSR. The other was to ‘provide information to world public opinion’ about this state of affairs and to operate with ‘some sort of publishing house’. The temptation was to go for the first, particularly since Amnesty was setting such a powerful example, but precisely because Amnesty (and the International PEN Club) were doing such a good job already, I felt that the second option would be the more original and interesting to try. Furthermore, I knew that two of our most active members, Stephen Spender and Stuart Hampshire, on the rebound from Encounter after disclosures of CIA funding, had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine, and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line. And finally, my own interests lay mainly in that direction. My experience had been in teaching, writing, translating and broadcasting. Psychologically I was too much of a shrinking violet to enjoy kicking up a fuss in public. I preferred argument and debate to categorical statements and protest, the printed page to the soapbox; I needed to know much more about censorship and human rights before having strong views of my own.

At that stage I was thinking in terms of trying to start some sort of alternative or ‘underground’ (as the term was misleadingly used) newspaper – Oz and the International Times were setting the pace were setting the pace in those days, with Time Out just in its infancy. But a series of happy accidents began to put other sorts of material into my hands. I had been working recently on Solzhenitzin and suddenly acquired a tape-recording with some unpublished poems in prose on it. On a visit to Yugoslavia, I called on Milovan Djilas and was unexpectedly offered some of his short stories. A Portuguese writer living in London, Jose Cardoso Pires, had just written a first-rate essay on censorship that fell into my hands. My friend, Daniel Weissbort, editor of Modern Poetry in Translation, was working on some fine lyrical poems by the Soviet poet, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, then in a mental hospital. And above all I stumbled across the magnificent ‘Letter to Europeans’ by the Greek law professor, George Mangakis, written in one of the colonels’ jails (which I still consider to be one of the best things I have ever published). It was clear that these things wouldn’t fit very easily into an Oz or International Times, yet it was even clearer that they reflected my true tastes and were the kind of writing, for better or worse, that aroused my enthusiasm. At the same time I discovered that from the point of view of production and editorial expenses, it would be far easier to produce a magazine appearing at infrequent intervals, albeit a fat one, than to produce even the same amount of material in weekly or fortnightly instalments in the form of a newspaper. And I also discovered, as Anthony Howard put it in an article about the New Statesman, that whereas opinions come cheap, facts come dear, and facts were essential in an explosive field like human rights. Somewhat thankfully, therefore, my one assistant and I settled for a quarterly magazine.

There is no point, I think, in detailing our sometimes farcical discussions of a possible title. We settled on Index (my suggestion) for what seemed like several good reasons: it was short; it recalled the Catholic Index Librorum Prohibitorum; it was to be an index of violations of intellectual freedom; and lastly, so help me an index finger pointing accusingly at the guilty oppressors – we even introduced a graphic of a pointing finger into our early issues. Alas, when we printed our first covers bearing the bold name of Index (vertically to attract attention nobody got the point (pun unintended). Panicking, we hastily added the ‘on censorship’ as a subtitle – Censorship had been the title of an earlier magazine, by then defunct – and this it has remained ever since, nagging me with its ungrammatically (index of censorship, surely) and a standing apology for the opacity of its title. I have since come to the conclusion that it is a thoroughly bad title – Americans, in particular, invariably associate it with the cost of living and librarians with, well indexes. But it is too late to change now.

Our first issue duly appeared in May 1972, with a programmatic article by Stephen Spender (printed also in the TLS) and some cautious ‘Notes’ by myself. Stephen summarised some of the events leading up to the foundation of the magazine (not naming Litvinov, who was then in exile in Siberia) and took freedom and tyranny as his theme:

Obviously there is a risk of a magazine of this kind becoming a bulletin of frustration. However, the material by writers which is censored in Eastern Europe, Greece, South Africa and other countries is among the most exciting that is being written today. Moreover, the question of censorship has become a matter of impassioned debate; and it is one which does not only concern totalitarian societies.

I contented myself with explaining why there would be no formal programme and emphasised that we would be feeling our way step by step. ‘We are naturally of the opinion that a definite need {for us} exists….But only time can tell whether the need is temporary or permanent—and whether or not we shall be capable of satisfying it. Meanwhile our aims and intentions are best judged…by our contents, rather than by editorials.’

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the course of the next few years it became clear that the need for such a magazine was, if anything, greater than I had foreseen. The censorship, banning and exile of writers and journalists (not to speak of imprisonment, torture and murder) had become commonplace, and it seemed at times that if we hadn’t started Index, someone else would have, or at least something like it. And once the demand for censored literature and information about censorship was made explicit, the supply turned out to be copious and inexhaustible.

One result of being inundated with so much material was that I quickly learned the geography of censorship. Of course, in the years since Index began, there have been many changes. Greece, Spain, and Portugal are no longer the dictatorships they were then. There have been major upheavals in Poland, Turkey, Iran, the Lebanon, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe. Vietnam, Cambodia and Afghanistan have been silenced, whereas Chinese writers have begun to find their voices again. In Latin America, Brazil has attained a measure of freedom, but the southern cone countries of Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Bolivia have improved only marginally and Central America has been plunged into bloodshed and violence.

Despite the changes, however, it became possible to discern enduring patterns. The Soviet empire, for instance, continued to maltreat its writers throughout the period of my editorship. Not only was the censorship there highly organised and rigidly enforced, but writers were arrested, tried and sent to jail or labour camps with monotonous regularity. At the same time, many of the better ones, starting with Solzhenitsyn, were forced or pushed into exile, so that the roll-call of Russian writers outside the Soviet Union (Solzhenitsyn, Sinyavksy, Brodsky, Zinoviev, Maximov, Voinovich, Aksyonov, to name but a few) now more than rivals, in talent and achievement, those left at home. Moreover, a whole array of literary magazines, newspapers and publishing houses has come into existence abroad to serve them and their readers.

In another main black spot, Latin America, the censorship tended to be somewhat looser and ill-defined, though backed by a campaign of physical violence and terror that had no parallel anywhere else. Perhaps the worst were Argentina and Uruguay, where dozens of writers were arrested and ill-treated or simply disappeared without trace. Chile, despite its notoriety, had a marginally better record with writers, as did Brazil, though the latter had been very bad during the early years of Index.

In other parts of the world, the picture naturally varies. In Africa, dissident writers are often helped by being part of an Anglophone or Francophone culture. Thus Wole Soyinka was able to leave Nigeria for England, Kofi Awoonor to go from Ghana to the United States (though both were temporarily jailed on their return), and French-speaking Camara Laye to move from Guinea to neighbouring Senegal. But the situation can be more complicated when African writers turn to the vernacular. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, who has written some impressive novels in English, was jailed in Kenya only after he had written and produced a play in his native Gikuyu.

In Asia the options also tend to be restricted. A mainland Chinese writer might take refuge in Hong Kong or Taiwan, but where is a Taiwanese to go? In Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, the possibilities for exile are strictly limited, though many have gone to the former colonising country, France, which they still regard as a spiritual home, and others to the USA. Similarly, Indonesian writers still tend to turn to Holland, Malaysians to Britain, and Filipinos to the USA.

In documenting these changes and movements, Index was able to play its small part. It was one of the very first magazines to denounce the Shah’s Iran, publishing as early as 1974 an article by Sadeq Qotbzadeh, later to become Foreign Minister in Ayatollah Khomeini’s first administration. In 1976 we publicised the case of the tortured Iranian poet, Reza Baraheni, whose testimony subsequently appeared on the op-ed page of the New York Times. (Reza Baraheni was arrested, together with many other writers, by the Khomeini regime on 19 October 1981.) One year later, Index became the publisher of the unofficial and banned Polish journal, Zapis, mouthpiece of the writers and intellectuals who paved the way for the present liberalisation in Poland. And not long after that it started putting out the Czech unofficial journal, Spektrum, with a similar intellectual programme. We also published the distinguished Nicaraguan poet, Ernesto Cardenal, before he became Minister of Education in the revolutionary government, and the South Korean poet, Kim Chi-ha, before he became an international cause célèbre.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Looking back, not only over the thirty years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

One of the bonuses of doing this type of work has been the contact, and in some cases friendship, established with outstanding writers who have been in trouble: Solzhenitsyn, Djilas, Havel, Baranczak, Soyinka, Galeano, Onetti, and with the many distinguished writers from other parts of the world who have gone out of their way to help: Heinrich Böll, Mario Vargas Llosa, Stephen Spender, Tom Stoppard, Philip Roth—and many other too numerous to mention. There is a kind of global consciousness coming into existence, which Index has helped to foster and which is especially noticeable among writers. Fewer and fewer are prepared to stand aside and remain silent while their fellows are persecuted. If they have taught us nothing else, the Holocaust and the Gulag have rubbed in the fact that silence can also be a crime.

The chief beneficiaries of this new awareness have not been just the celebrated victims mentioned above. There is, after all, an aristocracy of talent that somehow succeeds in jumping all the barriers. More difficult to help, because unassisted by fame, are writers perhaps of the second or third rank, or young writers still on their way up. It is precisely here that Index has been at its best.

Such writers are customarily picked on, since governments dislike the opprobrium that attends the persecution of famous names, yet even this is growing more difficult for them. As the Lithuanian theatre director, Jonas Jurasas, once wrote to me after the publication of his open letter in Index, such publicity ‘deprives the oppressors of free thought of the opportunity of settling accounts with dissenters in secret’ and ‘bears witness to the solidarity of artists throughout the world’.

Looking back, not only over the years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon. On the contrary, literature and censorship have been inseparable pretty well since earliest times. Plato was the first prominent thinker to make out a respectable case for it, recommending that undesirable poets be turned away from the city gates, and we may suppose that the minstrels and minnesingers of yore stood to be driven from the castle if their songs displeased their masters. The examples of Ovid and Dante remind us that another old way of dealing with bad news was exile: if you didn’t wish to stop the poet’s mouth or cover your ears, the simplest solution was to place the source out of hearing. Later came the Inquisition, after which imprisonment, torture and execution became almost an occupational hazard for writers, and it is only in comparatively recent times—since the eighteenth century—that scribblers have fought back and demanded an unconditional right to say what they please. Needless to say, their demands have rarely and in few places been met, but their rebellion has resulted in a new psychological relationship between rulers and ruled.

Index, of course, ranged itself from the very first on the side of the scribblers, seeking at all times to defend their rights and their interests. And I would like to think that its struggles and campaigns have borne some fruit. But this is something that can never be proved or disproved, and perhaps it is as well, for complacency and self-congratulation are the last things required of a journal on human rights. The time when the gates of Plato’s city will be open to all is still a long way off. There are certainly many struggles and defeats still to come—as well, I hope, as occasional victories. When I look at the fragility of Index‘s a financial situation and the tiny resources at its disposal I feel surprised that it has managed to hold out for so long. No one quite expected it when it started. But when I look at the strength and ambitiousness of the forces ranged against it, I am more than ever convinced that we were right to begin Index in the first place, and that the need for it is as strong as ever. The next ten years, I feel, will prove even more eventful than the ten that have gone before.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Michael Scammell was the editor of Index on Censorship from 1972 to August 1980.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Oct 2015 | mobile, News and features, United States

(Photo: Erica Jong)

There have always been sexual rebels.

In the 18th century, Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Mary Shelley, were fiercely rebellious about sexuality. They also were great feminists. In the 20th century, Emma Goldman spoke for women who believed love should be free.

Our age tends to divide things by decades and generalise about them. So, it’s assumed that the 70s and the second wave of feminism introduced sexual freedom to women. This is absolutely not true. If you read The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963), Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller (1934), or Ulysses by James Joyce (1922), you see that sexual rebels have always been with us.

What was different about [my 1973 novel] Fear of Flying was that it was a book that tried to reveal how women thought about sex in an age when most books about women didn’t show this. So, when the book came out both women and men were shocked. Some said: “Women don’t think like this!” and some said: “Thank God, somebody is talking about how women really think!” What was fascinating to me as an author was how contradictory the responses were.

I always wanted to write the books for women that did not exist. There is a huge gap between what we write about and what we think about. I wanted to rip the top of the head off a lusty woman and expose her fantasies to the light. Fantasies are important but they don’t necessarily have to become realities. The zipless fuck was a fantasy of perfect idealized sex with a stranger, but it is often impossible to fulfill. Many readers missed that.

Now I see woman writers writing about bondage and discipline, cruelty and submission, and I wonder whether that is fantasy too. I’ve never been much interested in submission, so I read these books as fairytale fantasies for women.

I think it’s important not to take literature literally. We turn to writers to document our dream lives. We turn to writers to show us what we are afraid to show ourselves. Many writers who become known for sexuality are not that different from you and me. They have a need to reveal the unconscious mind. If we take them literally, we miss the point.

The big change in sexual writing happened in the 1960’s when books like Lolita and Tropic of Cancer were liberated by the courts. The change in literature emerged from the change in the law. Male writers got very excited and produced books like John Updike’s Couples (1968) and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). Suddenly it was possible to publish these very honest works. I wanted to show honesty from a woman’s point of view. I was not advocating a kind of behavior, but many people did not understand that.

In Fear of Dying, I have also been attempting to reveal something unrevealed before. An editor once told me there had never been a bestseller about a woman over 40. But as I watched women growing older, still feeling sexy, looking for a way to overcome mortality, I realised that we needed new books that showed how women had changed.

Like Fear of Flying, Fear of Dying is such a book.

Erica Jong is a novelist whose works include Fear of Flying and the newly-published Fear of Dying. (Her books are available on Amazon, iTunes, Waterstones or your local independent bookshop.)

This article was originally published on FeedYourNeedtoRead.com and is reposted here with permission.

|

From the summer 1995 Index on Censorship magazine

Deliberately lewd

Erica Jong explains why pornography is to art as prudery is to the censors

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally. After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished.

Read the full article |

28 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile

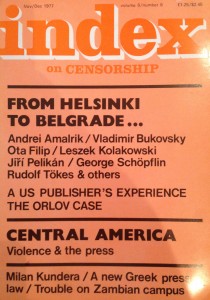

Index on Censorship magazine cover, November/December 1977

Novelist, playwright and short story writer Milan Kundera is one of the many Czech authors who, though they represent the best in their country’s contemporary literature, cannot publish their work in Prague. Acclaimed in France, where in 1973 he won a major literary prize for his last but one novel, and published in English, German, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Hebrew, Japanese and many other languages, he remains one of the 400 or more writers who are “on the index” in post-invasion, “normalised” Czechoslovakia.

Born in Brno forty-eight years ago, Kundera was until 1969 a professor at the Prague Film Faculty, his students including all the young film makers who were to bring fame to the Czechoslovak cinema in the sixties with such movies as The Firemen’s Ball, A Blonde in Love and Closely Observed Trains. In 1960 he published a highly influential essay, The Art of the Novel. Two years later the National Theatre put on his first play, The Owners of the Keys. Produced by Otomar Krejca, the play was an immediate success and was awarded the State Prize in 1963.

His first novel, The Joke, came out in 1967, being reprinted twice in a matter of months and reaching a total of 116,000 copies. This book, whose appearance was delayed by a long, determined struggle with the censor, opened the way to publication abroad, where Aragon called it one of the greatest novels of the century.

After the Soviet invasion Kundera was forced to leave the faculty, his work was no longer published in Czechoslovakia, all his books being removed from the public libraries. Since then, his works have only come out in translation. Life Is Elsewhere (see Index 4/1974, ppJ3-62) first appeared in Paris in 1973, where it won the Prix Medicis for the best foreign novel of the year. The French version of his latest novel, The Farewell Party, way published last year.

In 1975 Kundera was offered a professorship by the University of Rennes and obtained permission from the Czechoslovak authorities to go to France, which is now his second home. All his prose works now exist in English translation. (For an appraisal of his work, see Robert C. Porter’s article in Index 4/1975, pp.41-6). Unfortunately, The Joke – published by Macdonald in London and Coward McCann in New York in 1969 – was drastically cut without the author’s consent, forcing Kundera to write an indignant letter to the Times Literary Supplement, disclaiming all responsibility – an interesting case of a non-political, commercial censorship. The irony of the situation was certainly not lost on the author, who is a master of the genre. His collection of short stories, Laughable Loves (with a foreword by Philip Roth) and his other two novels have since been published by Knopf, and The Farewell Party has just been brought out by John Murray in London.

This selection of Kundera’s stimulating and often provocative views on such topics as the writer in exile, committed literature, the death of the novel, the nature of comedy, and so on, has been compiled by George Theiner.

Writing for translator

I am certainly in a rather odd situation. I write my novels in Czech. But since 1970 I have not been allowed to publish in my own country, and so no one reads me in that language. My books are first translated into French and published in France, then in other countries, but the original text remains in the drawer of my desk as a kind of matrix.

In the autumn of 1968 in Vienna I met a fellow-countryman, a writer, who had decided to leave Czechoslovakia for good. He knew that this meant his books would no longer be published there. I thought he was committing a form of suicide, and I asked him if he was reconciled to writing only for translators in future, if the beauty of his mother tongue had ceased to have any meaning for him. When I returned to Prague, I had two surprises in store for me: even though I didn’t emigrate, I too was forced from then on to write for translators only. And, paradoxical as it may seem, I feel it has done my mother tongue a lot of good.

Conciseness and clarity are, for me, what makes a language beautiful. Czech is a vivid, suggestive, sensuous language, sometimes at the expense of a firm order, logical sequence and exactitude. It contains a strong poetic element, but it is difficult to convey all its meanings to a foreign reader. I am very concerned that I should be translated faithfully. Writing my last two novels, I particularly had my French translator in mind. I made myself-at first unknowingly-write sentences that were more sober, more comprehensible. A cleansing of the language. I have a great affection for the eighteenth century. So much the better then if my Czech sentences have to peer carefully into the clear mirror of Diderot’s tongue.

Goethe once said to Eckermann that they were witnessing the end of national literature and the birth of a world literature. I am convinced that a literature aimed solely at a national readership has, since Goethe’s time, been an anachronism and fails to fulfil its basic function. To depict human situations in a way which makes it impossible for them to be understood beyond the frontiers of any single country is a disservice to the readers of that country too. By so doing we prevent them from looking further than their own backyard, we force them into a straitjacket of parochialism. Not to have one’s work published in one’s own country is a cruel lesson, but I think a useful one. In our times we must consider a book that is unable to become part of the world’s literature to be non-existent.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

Central Europe

As a Czech writer I don’t like being pigeon-holed in the literature of Eastern Europe. Eastern Europe is a purely political term barely thirty years old. As far as cultural tradition is concerned, Eastern Europe is Russia, whereas Prague belongs to Central Europe. Unfortunately, West Europeans don’t know their geography. This ignorance could be fatal, as indeed it has proved to be in the past. Remember Chamberlain in 1938 and his words about “a small country we know little about”.

The nations of Central Europe are small and far too well concealed behind a barrier of languages which no one knows and few study. And yet it is this very part of Europe which, over the past fifty years, has become a kind of crucible in which history has carried out incredible experiments, both with individuals and with nations. And the fact that those living in Western Europe have only very simplified notions, have never taken the trouble properly to study what is going on a few hundred kilometres from their own tranquil homes can, I repeat, be fatal to them.

From this Central Europe have come several major cultural impulses, without which our century would be unthinkable: Freud’s psychoanalysis; Schonberg’s dodecaphony; the novels of Kafka and Hasek, which have discovered a grotesque new literary world and the new poetry of the non-psychological novel; and finally structuralism, born and developed in Prague in the twenties, to become a fashion in West Europe thirty years later. I grew up with these traditions and have little in common with Eastern Europe. Forgive me if I seem to dwell on these ridiculous geographical details.

Small nations

Large nations are obsessed with the idea of unification. They see progress in unity. Even President Carter’s message to the inhabitants of outer space contains a passage expressing regret that the world is as yet divided into nations and the hope that it will soon come together in a single civilisation. As if unity were a cure for all ills. A small nation, in its efforts to maintain its very existence, fights for its right to be different. If unification is progress, then small nations are anti-progressive to the core, in the finest sense of the word. Big nations make history, small ones receive its blessings. Big nations consider themselves the masters of history and thus cannot but take history, and themselves, seriously. A small nation does not see history as its property and has a right not to take it seriously.

Franz Kafka was a Jew, Jaroslav Hasek a Czech – both members of a minority. When the First World War broke out, Europe was seized by a paroxysm of warlike nationalism, which did not spare even Thomas Mann or Apollinaire. In Franz Kafka’s diary we can read: “Germany has declared war on Russia. Went swimming in the afternoon“. And when, in 1914, Hasek’s Schweik learns that Ferdinand has been killed, he asks which one – the barber’s apprentice who once drank some hair oil, or was it the Ferdinand who collects dogshit on the pavement?

They say the greatness of life is to be found only where life transcends itself. But what if all transcendent life is history – which does not belong to us anyway? Is there only Kafka’s absurd

office? Only the daftness of Hasek’s army? Where then is the greatness, the gravity, the meaning of

it all? The genius of the minorities has discovered a world without gravity and greatness. Discovered its grotesqueness. Hegel’s concept of history -wise and ascending, like assiduous schoolgirls, ever higher on the staircase of progress – has been inconspicuously buried by Hasek and Kafka. In this sense we are their heirs.

Our Prague humour is often difficult to understand. The critics took Miloš Forman to task because in one of his films he made the audience laugh where they shouldn’t. Where it was out of place. But isn’t that just what it is all about? Comedy isn’t here simply to stay docilely in the drawer allotted to comedies, farces and entertainments, where “serious spirits” would confine it. Comedy is everywhere, in each one of us, it goes with us like our shadow, it is even in our misfortune, lying in wait for us like a precipice. Joseph K. is comic because of his disciplined obedience, and his story is all the more tragic for it. Hasek laughs in the midst of terrible massacres, and these become all the more un- bearable as a result. You see, there is consolation in tragedy. Tragedy gives us an illusion of greatness and meaning. People who have led tragic lives can speak of this with pride. Those who lack the tragic dimension, who have known only the comedies of life, can have no illusions about themselves.

When I came to France, the thing that astonished me most was the difference in national humour. The French are immensely humorous, witty, gay. But they take themselves and the world seriously. We are far more sad, but we take nothing seriously.

Committed literature

All my life in Czechoslovakia I fought against literature being reduced to a mere instrument

of propaganda. Then I found myself in the West only to discover that here people write about the literature of the so-called East European countries as if it were indeed nothing more than a propaganda instrument, be it pro- or-anti- Communist. I must confess I don’t like the word “dissident”, particularly when applied to art. It is part and parcel of that same politicising, ideological distortion which cripples a work of art. The novels of Tibor Dery, Miloš Forman’s films – are they dissident or aren’t they? They cannot be fitted into such a category. If you cannot view the art that comes to you from Prague or Budapest in any other way than by means of this idiotic political code, you murder it no less brutally than the worst of the Stalinist dogmatists. And you are quite unable to hear its true voice. The importance of this art does not lie in the fact that it accuses this or that political regime, but in the fact that, on the strength of social and human experience of a kind people over here cannot even imagine, it offers new testimony about the human conditions.

If by “committed” you mean literature in the service of a certain political creed, then let me tell you straight that such a literature is mere, conformity of the worst kind.

A writer always envies a boxer or a revolutionary. He longs for action and, wishing to take a direct part in real life, makes his work serve immediate political aims. The nonconformity of the novel, however, does not lie in its identification with a radical, opposition political line, but in presenting a different, independent, unique view of the world. Thus, and only thus, can the novel attack conventional opinions and attitudes.

There are commentators who are obsessed with the demon of simplification. They murder books by reducing them to a mere political interpretation. Such people are only interested in so-called “Eastern” writers as long as their books are banned. As far as they’re concerned, there are official writers and opposition writers – and that is all. They forget that any genuine literature eludes this sort of evaluation, that it eludes the Manichaeism of propaganda.

There are historical situations which open people’s souls the way you open a tin of sardines. Without the key offered to me by my country’s recent history, I would not, for instance, have been able to discover in Jaromil’s soul the incredible coexistence of the Poet and the Informer.

We have got into the habit of putting the blame for everything on “regimes”. This enables us not to see that a regime only sets in motion mechanisms which already exist in ourselves. A novel’s mission is not to pillory evident political realities but to expose anthropological scandals.

The death of the novel

Since the twenties, everyone seems to have been writing the obituary of the novel – the Surrealists, the Russian avant-garde, Malraux, who claims the novel has been dead since the time Malraux stopped writing novels, and so on and so forth. Isn’t it strange? No one talks about the death of poetry. And yet, since the great generation of Surrealists, I know of no truly great and innovatory work of poetry. No one talks about the death of the theatre. No one talks about the death of painting. No one talks about the death of music. Yet, since Schonberg, music has abandoned a thousand-year-old tradition based on tonality and on musical instruments. Varese, Xenakis . . . I am very fond of them, but is this still music? In any case, Varese himself preferred to speak about the organisation of sound rather than music. So, music may have been dead for several decades, yet no one talks about its demise. They talk about the death of the novel, though this is possibly the least dead of all art forms.

To speak of the end of the novel is a local preoccupation of West European writers, notably the French. It’s absurd to talk about it to a writer from my part of Europe, or from Latin America. How can one possibly mumble something about the death of the novel and have on one’s bookshelf A Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez? As long as there is human experience which cannot be depicted except in a novel, all conjectures about its having expired are mere expressions of snobbery. It is, of course, possibly true to say that the novel in Western Europe no longer provides many new insights and that for those we have to look to the other part of Europe and to Latin America.

I expect that all this talk of the death of the novel is due to the eschatological thinking of the avant-garde. Spurred on by revolutionary illusions, the avant-garde dreamed of installing a completely new art, a new era. If you like, in the spirit of Marx’s well-known saying about the prehistory and the history of mankind. From this point of view, the novel would belong to prehistory, while history would be ruled by poetry, in which all earlier genres would dissolve and vanish. It’s quite remarkable how this eschatological concept, utterly irrational though it is, has gained general acceptance, becoming one of the commonest clichis of the contemporary snob. He despises the novel, preferring to speak of’ a text’. According to him, the novel is a thing of the past (the prehistory of letters), and this in spite of the fact that the greatest strength of literature over the past 50 years has been in that very sphere-just take Robert Musii, Thomas Mann, Faulkner, Celine, Pasternak, Gombrowicz, Giinter Grass, Boll, or my dear friends, Philip Roth and Garcia Marquez.

The novel is a game with invented characters. You see the world through their eyes, and thus you

see it from various angles. The more differentiated the characters, the more the author and the reader have to step outside themselves and try to understand. Ideology wants to convince you that its truth is absolute. A novel shows you that everything is relative. Ideology is a school of intolerance. A novel teaches you tolerance and understanding. The more ideological our century becomes, the more anachronistic is the novel. But the more anachronistic it gets, the more we need it. Today, when politics have become a religion, I see the novel as one of the last forms of atheism.

When I was a boy I used to idealise the people who returned from political imprisonment. Then I discovered that most of the oppressors were former victims. The dialectics of the executioner and his victim is very complicated. To be a victim is often the best training for an executioner. The desire to punish injustice is not only a desire for justice, pure and simple, but also a subconscious desire for new evil…

Jacob knows all this when he thinks about others. He does not know it in relation to himself. So that all it needs is a single unguarded moment, when his reason takes a nap, and his subconscious dislike of people, his suppressed hatred, take over and an innocent girl dies. The more noble a person is, the darker the shadow of suppressed evil within.

A true novel always stands beyond hope and despair. Hope is not a value, merely an unproven supposition that things will get better. A novel gives you something far better than hope. A novel gives you joy. The joy of imagination, of narration, the joy provided by a game. That is how I see a novel – as a game. One of the characters in The Farewell Party occasionally has a halo round his head. The spa gynaecologist cures his patients by injecting his own semen and becomes the father of many children. Am I being serious, or is it just a joke? It is a game . . .

Of course, if the game is to be worthwhile, it must be played and must be about something serious. It must be a game with fire and demons. The game of the novel combines the lightest and the hardest, the most serious with the most light-hearted.

Milan Kundera is a Czech-born writer who has been living in exile in France since 1975.

This article is from the November/December 1977 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

This article is from the November/December 1977 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]