Spies, Secrets and Lies: Index magazine launch at the Frontline Club

Xiaolu Guo is a fiction writer, filmmaker and political activist. Robert McCrum is an associate editor of The Observer. Stephen Grey is an investigative journalist and author. Ismail Einashe is a journalist and researcher. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

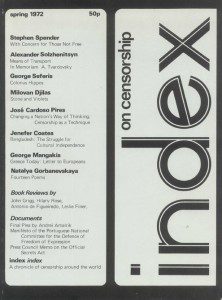

Are the challenges of censorship, subterfuge and propaganda greater or lesser than they were in previous decades? Who are modern technological advances really empowering? It was a full house last night at the Frontline Club for the launch of Spies, Secrets and Lies — Index on Censorship’s Autumn 2015 issue — and a lively debate on censorship then and now.

The panel — chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley — included award-winning investigative journalist and author Stephen Grey; fiction writer, filmmaker and political activist Xiaolu Guo; associate editor of The Observer Robert McCrum; and freelance journalist, researcher and an associate editor at foreign affairs magazine Warscapes, Ismail Einashe.

In 2010, when Grey was trying to work out how he and Julian Assange could get the Iraq war logs into Britain without being blocked along the way, he invited Assange to a panel at City University London moderated by former Index on Censorship chair Jonathan Dimbleby. “We thought the British government would never stop anyone coming to a censorship debate in London,” says Grey. And it worked.

.@StephenGrey introducing our event. Talking about trying to get Julian Assange into country for an index event years ago #indexfrontline

— IndexCensorshipMag (@Index_Magazine) October 13, 2015

“The river of information that came out of Wikileaks -- and subsequently Snowden, in a more restricted way -- is just one facet of this explosion of free knowledge and rapid messaging that defines our world today, to which our politics and security services have yet to adapt,” says Grey.

But how does this situation differ from the flow of information during the Cold War?

Most obviously, technological advances have changed the way we operate. Harking back to his early days at Index on Censorship in the 1970s, McCrum told of how his first trip to Czechoslovakia was with a carrier bag of bananas in which he smuggled editions of the magazine (Full story in the latest magazine, paywall). Today, the ease of moving documents has made tackling censorship less labourious.

Robert McCrum on how when the magazine was founded, there was a clear enemy in Cold War. there were clearer lines #indexfrontline

— IndexCensorshipMag (@Index_Magazine) October 13, 2015

Index was founded to defend literary freedom during the Cold War. “Now we’re trying to defend freedom of speech and freedom of thought across the globe,” says McCrum.

Take China, where state surveillance is a daily occurrence. “Since the internet started in China 20 years ago, it created great freedom,” says Guo. “But it also promoted overwhelming state control and at the moment, there's at least 2 million internet police.” While no government has a monopoly on cyber surveillance, China’s efforts are certainly more advanced, she explains.

Discussing whether there is more or less censorship today, Einashe says that in Africa we can clearly see there is more. “Freedom House says that the democratic gains you had in the continent in the early 2000s have now reversed, so you have a situation where things are becoming less democratic and states are becoming less free.”

Yes, @IsmailEinashe reminds us that censorship not just something happening far away, under regimes #indexfrontline https://t.co/b72bf4A3yp — IndexCensorshipMag (@Index_Magazine) October 13, 2015

But our focus shouldn’t just be on far away places, he explains. Even in the West we see censorship on a daily basis, including here in the UK. In recent weeks, we've seen the banning of Homegrown, a play about the radicalisation of young people and the seductive power of Isis. We also saw the secular activist Maryam Namazie banned from speaking at Warwick University's student union, since resolved, for fear she would incite hatred against Muslims.

So has censorship really changed? Flicking through a copy of the latest Index magazine, it's very difficult to tell, says Grey.

On one hand, we have more openness and transparency than during the Cold War. “We also have an age of mass surveillance, where communication is there to be mined and monitored,” he says.

Professor Chris Frost, Tim Hetherington Fellowship winner Josie Timms and Judith Hetherington. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Index rounded off the night with the presentation of the first Liverpool John Moores/Tim Hetherington/Index on Censorship Fellowship to new journalism graduate Josie Timms.

Tim Hetherington was a British photojournalist, most famous for his award-winning documentary Restrepo about the war in Afghanistan. He was killed in 2011 by shrapnel from artillery fired by Libyan forces while covering the Libyan civil war.