South Koreans clash over history books

South Korea is embroiled in a “textbook war” over what high school students learn in history class. With schools selecting their textbooks for the coming academic year, objections have been raised to one textbook that critics felt distorted the country’s history of Japanese occupation and military dictatorship. A storm of conflict has followed, raising questions over longstanding disagreements regarding how to interpret history, what young people should learn and who gets to decide on the material they study from.

The controversy started in September after the Ministry of Education gave tentative approval to a book written and published by a company called Kyohak, which is known for its right-wing leanings. After receiving tentative approval, the Kyohak book was selected for the 2014 academic year (which starts in March) by around 20 schools, a small portion of the 800 high schools nationwide.

Liberal critics argued that the textbooks misrepresented some aspects of contemporary South Korean history. In particular, they said the books painted an inaccurately rosy picture of Korea’s colonial occupation by Japan and provided an airbrushed account of the military dictatorships that held power from the 1960s through to the democratization movement of the late 1980s, when the government in Seoul softened up and agreed to elections before hosting the 1988 Summer Olympics.

The choice of the Kyohak books led to an outcry from left wing civic groups across the country, who protested at schools and government offices in an attempt to pressure the schools to cancel their selections. All but one of the 20 schools that selected the Kyohak books have since cancelled their orders for them and said they’ll use different books. The one school that hasn’t cancelled its selection is reportedly “reconsidering” its decision to use the Kyohak book in class.

But parents and activists on the other side of the political spectrum, who are more in line with the account of history presented in the Kyohak books, have argued that the liberal groups’ pressure to change the textbooks amounts to intimidation and an infringement on the schools’ rights to use the book of their choosing.

Kyohak called the campaign to keep its textbooks out of classrooms a “witch hunt” and argued that as the book had gained government approval, schools were free to select and use it if they chose.

The Ministry of Education then conducted an investigation into the schools that selected the Kyohak books and then changed their minds. It concluded that the cancellations were made due to “relentless criticism from civic groups”, as Deputy Minister of Education Na Seung-il said in a Jan. 8 press briefing.

If high school history textbooks seem like a silly thing to fight over, consider the lasting controversy over history in South Korea. The antagonism illustrated in this discussion of high school history textbooks is born of a deep, long-standing split in South Korean society: The country is still roughly divided over those who benefited from the Japanese colonial occupation (1910-1945) and those who were harmed by it. South Korean politics and media are still characterised by a left-right divide where the two sides agree on almost nothing and undermine anything associated with the other side.

In the controversy over the Kyohak books, and in discussions of South Korean history generally, the interpretation of the rule of former President Park Chung-hee (1961-1979) is a particular point of contention. After Korea became independent from Japan, Park used reparation money to establish the infrastructure and industrial base that made South Korea’s economic miracle possible. During his rule, he suspended nearly all civil liberties and ruled as a military dictator. Whether he should be remembered as a father of a successful nation or a brutal dictator who trampled on the nation’s rights is still a matter of heated debate. The Kyohak books were accused of highlighting only the benefits of his policies and ignoring the human cost.

This recent furor over Kyohak has also reignited a conversation that Park initiated when he was president. In 1974, he initiated a system whereby all schools nationwide used one official textbook, which allowed the government to control what students learned in school about their country’s history . The books told students that the coup d’etat that brought Park to power and the lack of rights enjoyed by South Korean citizens were necessary for the country’s security and advancement.

The system whereby all schools used one state-designated history textbook was ended in the mid-1990s and autonomy was granted to schools to select their own textbooks. Last week, members of the ruling Saenuri Party floated the idea of returning to the system of state-designated textbooks, ostensibly to avoid ugly episodes like the recent friction over the Kyohak books.

Current President Park Geun-hye is the daughter of Park Chung-hee. One year into her rule, many have accused her of reverting to dissent-quashing tactics that are reminiscent of her father’s time in power. The same critics who objected to the Kyohak books see the suggestion of state textbooks as opportunist move by the government, and an attempt to take control over what all young people learn.

This article was posted on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

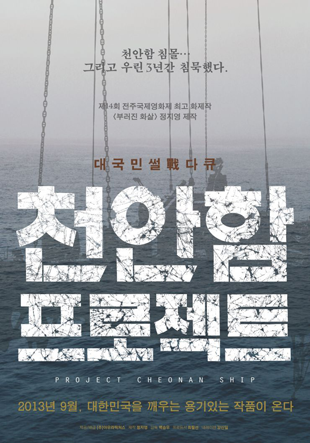

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.