Mapping Media Freedom: Journalists barred from covering Theresa May event

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

United Kingdom: Journalists prevented from covering Theresa May visit

2 May 2017 – Three journalists for Cornwall Live were shut in a room, prevented from filming and severely limited on what questions they could ask during British Prime Minister Theresa May’s visit to a factory in Cornwall called AP Diving.

A reporter from Cornwell Live who was live blogging the event wrote: “We’ve been told by the PM’s press team that we were not allowed to stand outside to see Theresa May arrive.”

He later added: “PM is here – but we’ve been shown the door. The prime minister is behind this door – but we can’t show you. Her press team has said print journalists are not allowed to see her visiting the company.”

The journalist then described conditions surrounding the interview with May: “We’ve been allowed to ask our questions to the prime minister (although we are forbidden to film or photograph her answering them).”

The Netherlands: Journalist faces rape threats following post on popular blog

7 May 2017 – Loes Reijmer, a journalist and columnist for De Volkskrant, has faced a storm of abuse after the popular right-wing blog Geenstijl published her photo with the text: “Would you do her?”

Thousands of readers responded in the comments section, many containing sexual comments and rape threats.

Reijmer had published several critical columns about the controversial weblog Geenstijl, a provocative online portal, owned by Telegraaf Media Group and is one of the most popular news sites in the Netherlands. Geenstijl has faced years of criticism for similar posts.

The attack on Reijmer led to a public call on advertisers to boycott Geenstijl and it’s affiliate video blog Dumpert. The dailies De Volkskrant and NRC published an open letter on 6 May 2017 signed by over a hundred women from media and entertainment calling big companies to pull out their advertisement because they “support humiliation of women”. Over the following days, many advertisers withdrew their adverts.

The Dutch Union for Journalists has condemned Geenstijl in a statement on their website: “The tarnish way in which journalists like Reijmer are being attacked by readers, this provocation by Geenstijl, is one of many cases of intimidation of journalists. In this case, it was sexual harassment, something that female journalists who have the guts to be critical are increasingly facing, which is unacceptable.”

Azerbaijan: Manager of independent online TV channel detained

2 May 2017 – Aziz Garashoglu, one of the managers of an online TV platform Kanal 13, was detained and then sentenced to 30 days in administrative detention.

Garashoglu was detained together with his wife Lamiya Charpanova who is an editor at the channel. Both were questioned for more than an hour.

Charpanova was released, while her husband was taken to Nasimi district court where he was sentenced to 30 days in administrative detention on charges of allegedly resisting the police.

Speaking to journalists after the hearing, lawyer Elchin Sadigov said Aziz was rounded up for his alleged resemblance to a man named Faig Cabbarov, who has been on the list of fugitives since 2015. But the lawyer also confirmed that after seeing the picture it was clear there was no resemblance.

Sadigov said he will be appealing the decision. Kanal 13 was founded in 2010 as an independent online television. One of the founders of the website lives in exile in Germany.

France: Vice journalist injured by police while covering May Day march

1 May 2017 – Videojournalist Henry Langston, who works for Vice UK, was hit by police officers and then injured by a piece of tear gas canister while reporting on a May Day march in Paris, Langston reported on Twitter and confirmed to Mapping Media Freedom.

The journalist said he was first hit across the knee with a baton by an officer.

Langston reported that the protest was “very violent on both sides” and that he and his crew were “following a group of anarchists” during the incident.

“Police officers were aiming flash-balls (a non-lethal hand-held weapon) at people’s heads, firing tear gas canisters directly at people. It seems to me they weren’t differentiating between protesters and journalists”.

“Later, the crowd was trapped against a wall. Police hit you [with batons] no matter who you were. Then they let people out and continued hitting them. I was wearing a helmet that said TV and they hit me anyway”, Langston continued.

An hour later Langston said he was hit in the leg by what he alleges “was a mechanism from a tear gas canister”. Langston was treated in hospital for injuries where he received stitches.

His cameraperson, freelancer Devin Yuceil, was also hit in the stomach with a piece of a flash grenade.

Greece: Masked assailants attack Kathimerini offices

24 April 2017 – A group of about 10 masked individuals barged into the offices of Greek daily Kathimerini in Thessaloniki, throwing paint and flyers.

According to a report published on the news website protagon.gr, the flyers had threats written on them, including: “good news is a stone on a journalist’s head”.

The Athens Union of Journalists (ESIEA) published a press release on Monday, following the attack: “The board of ESIEA expresses its support to the colleagues and all the employees of the newspaper and notes that such actions, wherever they come from, will not weaken the morale of journalists for [providing] objective information but the state must do its duty.”

The press released emphasised that journalists and their unions do not give in to blackmails and intimidation attempts pursued by “dark circles”.

All the Greek political parties condemned the attack. The government-leading Syriza said in a statement that acts against the freedom of the press “have no place in the political confrontation,” while the main opposition party, New Democracy expressed its “unequivocal condemnation of the attack by anarchists”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

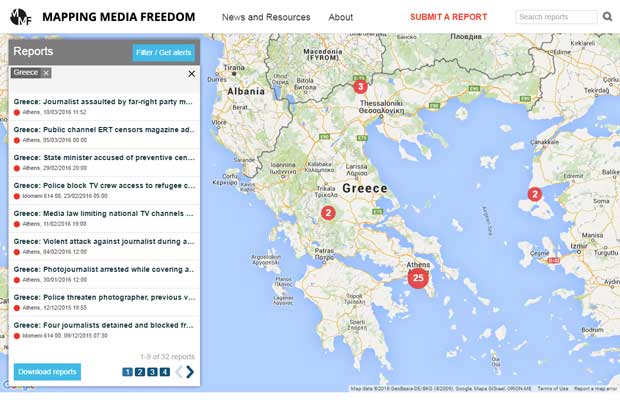

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1494498939864-9d0448a9-e2e1-3″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]