Interview: Judy Blume and her battle against the bans

Judy Blume (Photo: Elena Seibert)

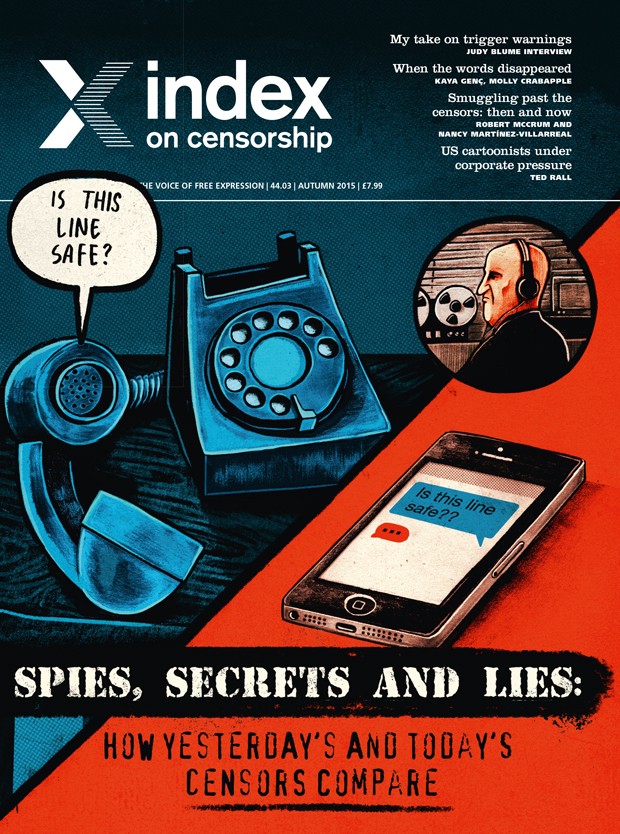

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

“Why did you kill the pet turtle?” The question took author Judy Blume by surprise on a recent US book tour. The child asking it was referring to a novel first published in 1972, Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, where Dribble, the pet turtle, is accidentally swallowed by the protagonist’s younger brother. “I’d never heard that complaint before,” Blume told Index on a recent trip to the UK. “People found it funny before, but now I can expect animals-have-feelings-too complaints. Those sorts of questions strike you as funny, but it’s awful too. It’s the adults behind them that are the problem.”

Blume, who has sold 80 million books and been translated into 32 languages, has nothing against turtles, or indeed children’s attachment to pets. But she talks of the “new, very protective” approach to reading that she is seeing more and more. “It’s the job of a parent to help children deal with unexpected things that happen,” said the Florida-based writer, best known for her teen titles. “I often get letters saying, ‘We didn’t like it when this thing happened in your book, so we’re not going to read any of them again.’”

By tackling coming-of-age issues, including sex and puberty, she has experienced various cries of outrage along the way, as well as outright bans by some schools and libraries. In 2009, her publisher even had to send her a bodyguard, after she was deluged with hate-mail and threats for speaking out in support of Planned Parenthood, a US pro-choice group. Five Judy Blume books feature in the 100 most frequently challenged list (1990 to 1999), compiled by the American Library Association, which tracks attempts to ban or censor literature, often by US school boards.

Like many people, I grew up with Judy. I was 11 by the time I had devoured most of her back catalogue. I remember a battered paperback of Forever – the infamous teen sex novel – being passed around my class like contraband, although all our parents and teachers must have known we had it. Her writing about periods was far more enlightening than anything we were taught at school. I still remember the nurse who came into our class and frightened the hell out of us by waving a super-size tampon in the air. “My mum has those!” one school friend said proudly. Her mum was French. I was sure mine didn’t mess with such things.

A US website, Flavorwire, recently compiled a list of “awkward Judy Blume moments” from people’s youth. There was one where a local librarian lent her eight-year-old grandson the novel about a girl’s first period and he wept at the sheer horror of it. There was another about a nine-year-old who had a public tantrum and screamed “Censorship!” at the top of her voice when told she was “not ready” for Judy. Perhaps the most enlightening, however, was the person who admitted trying to get Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret removed from the library because she thought it questioned the existence of God. “I didn’t read it until years later, far past the time when my fundamentalism had lapsed,” she confessed, inadvertently playing a part in the long tradition that sees the most vocal criticism of books coming from those who haven’t read them.

“I’ve always said censorship is caused by fear,” Blume told Index, while on tour to launch her latest book In the Unlikely Event. As a board member of the National Coalition Against Censorship in the US, she has long spoken with passion about her views on the freedom to read, and against books being censored.

Among the most recent children’s books to be targeted in the US are Jeanette Winter’s The Librarian of Basra and Nasreen’s Secret School, which are based on true stories from Iraq and Afghanistan, respectively. Parents from Florida’s Duval County created a petition in July to object to the books references to Islam and war.

“I don’t use age ratings. There’s no reason why someone who wants to, can’t read it. I don’t believe in saying books are for certain age groups,” said Blume, when asked, at a recent UK event at King’s Place, London, if she thought her newest book, written for adults, should be restricted to readers of a certain age.

If censorship had an agony aunt, it would be Blume. Throughout her long career, she’s tackled the big issue openly and without judgement. “Am I being a censor?” a mother asked her recently, after confessing she omitted a section of Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing when she read it to her children. It was a segment where a father is left in charge of his two sons and makes a real hash of it by not knowing how to handle them. “The mother decided not to read that part to her own boys, because she didn’t want them to know how other dads are,” said Blume. “That’s your choice. But my advice is read it all. Talk about it, laugh about it. Say: ‘Aren’t we glad our dad is different?’ No, it’s not censorship. It’s your decision. But are you going to do them any favours by trying to protect them?”

And then comes the thing that makes Blume “very, very upset”: trigger warnings. These are cautions put on books or reading lists to warn of potentially upsetting content, and they are becoming a growing practice at US colleges. Blume only came across the term recently, but instantly took it very seriously. “Why do college students need to be warned that what they are about to read might make them feel bad? These are 20-year-olds, but they need a professor to warn them? What kind of education is that? It makes me crazy.”

The author, who was listed by the US Library of Congress in the living legend category of writers and artists in 2000, also expressed concern about hearing of writers being “dis-invited” from US schools and universities for things they have written or said. “This can be over one incident in a 400-page book,” she said. “I thought the idea of education was to exchange ideas and discuss. How we learn from one another?” Nonetheless, she’s optimistic that this fearful attitude can be fought against. She has already seen professors and teachers standing up to it.

One thing Blume adamantly doesn’t want to see is a return to 1980s America, which was the worse period she has witnessed for freedom to read, and when controversial books were stripped out of classrooms. She believes there has been a return from the precipice of the Reagan era, yet there are still attempts to exert too much control. She referred, very enthusiastically, to The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, which has also caused a stir and was pulled from the curriculum in Idaho schools. What’s the problem with it I ask? “The language, the sexuality, all things related to life as a teenage boy. It’s like saying it’s a bad thing to be a teenage boy!”

“It’s the kids’ right to read,” she said resolutely as our conversation came to a close and she prepared to continue her whirlwind tour. It’s a mantra she’s been repeating for decades. At 77 and still as dynamic as ever, she shows no sign of stopping anytime soon.

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.