“Censure me in your wisdom”: Bowdlerized Shakespeare in the nineteenth century

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

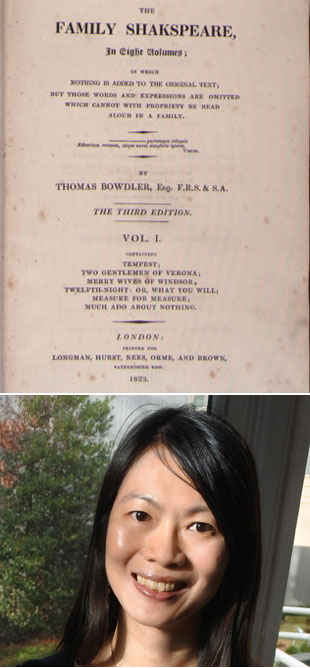

American academic Alexa Huang explores how Shakespeare’s plays were edited to make them more acceptable to Victorians.

Shakespeare has been used to divert around censorship, “sanitised” and redacted for children, young adults and school use, and even used as a form of protest all over the world. While censors have reacted differently to Shakespeare (sometimes with a blind eye), self-censorship (by directors and audiences) is part of the picture as well.

Not all censors work in the capacity of a public official. Many censors are in fact editors, writers and educators who are gatekeepers of specific forms of knowledge. Julius Caesar, for example, is often deemed one of the more appropriate plays to teach and perform in American school systems, because the themes of honor, free will and principles of the republic (as opposed to more sexually charged themes in other plays) are considered inspiring and suitable in the educational context.

The themes in such plays as Romeo and Juliet (teen exuberance and sex), The Merchant of Venice (anti-Semitism), Othello (racism and domestic violence), and Taming of the Shrew (sexism) make modern audiences uncomfortable, but they compel us to ask harder questions of our world.

While Shakespeare has been a large part of American cultural life, the “Shakespeare” that is taught and enacted in schools has often been redacted and even censored. But this is not a new phenomenon. The history of bowdlerized Shakespeare goes back to the nineteenth century. To bowdlerize a classic means to expurgate or abridge the narrative by omitting or modifying sections that are considered vulgar.

In fact, the term “bowdlerized” comes from Henrietta “Harriet” Bowdler who edited the popular, “family-friendly” anthology The Family Shakespeare (1807) which contains 24 edited plays. The anthology sanitised Shakespeare’s texts and rid them of undesirable elements such as references to Roman Catholicism, sex and more. The anthology was intended for young women readers.

Multiple ambiguities in Shakespeare are replaced by a more definitive interpretation. Ophelia no longer commits suicide in Hamlet. It is an accidental drowning. Lady Macbeth no longer curses “out, damned spot” but instead she says “Out, crimson spot!” Prostitutes are omitted, such as Doll Tearsheet in Henry IV Part 2. The “bawdy hand of the dial” (Mercutio) in Romeo and Juliet is revised as “the hand of the dial.”

Contrary to popular imagination, censorship is not a top-down operation. Instead, it is often a communal phenomenon involving both the censors and the receivers who willingly accept the Shakespeare that has been improved upon. Family Shakespeare was itself a family project. Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825) worked with his sister Henrietta Bowdler to bowdlerize or clean up the classics. The subtitle of the volume states that “nothing is added to the original text; but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.” Shakespeare is credited as the author, though Bowdler made clear the Bard needed quite some heavy-handed editing.

Ironically, Henrietta Bowdler was herself censored. Thomas Bowdler’s name appears on the cover. It took two centuries for Henrietta to be credited for the anthology, for obviously there is no way she could have admitted that she recognised the bawdy puns in Shakespeare, much less editing them out of Shakespeare. The Bowdlers are among the better-known “censors” in the nineteenth century who editorialised the classics including Shakespeare.

When laying out her editorial principles in the preface, Bowdler does not hesitate to criticise the “bad taste of the age in which [Shakespeare] lived” and Shakespeare’s “unbridled fancy”:

The language is not always faultless. Many words and expressions occur which are of so indecent Nature as to render it highly desirable that they should be erased. But neither the vicious taste of the age nor the most brilliant effusions of wit can afford an excuse for profaneness or obscenity; and if these can be obliterated the transcendent genius of the poet would undoubtedly shine with more unclouded lustre.

She further explains her motive in The Times in 1819, emphasising that the “defects” in Shakespeare have to be corrected:

My great objects in the undertaking are to remove from the writings of Shakespeare some defects which diminish their value, and at the same time to present to the public an edition of his plays which the parent, the guardian and the instructor of youth may place without fear in the hands of his pupils, and from which the pupil may derive instruction as well as pleasure: and without incurring the danger of being hurt with any indelicacy of expression, may learn in the fate of Macbeth, that even a kingdom is dearly purchased, if virtue be the price of acquisition

While censorship carries a negative connotation in our times, The Family Shakespeare did broaden Shakespeare’s audience and readership. While American schools continue to redact Shakespeare, they also infuse Shakespeare into the American cultural life in various forms.

Alexa Huang will be participating in the Index on Censorship magazine panel at the Hay Festival.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91322″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229008534812″][vc_custom_heading text=”Bowdler revisited: Shakespeare

” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229008534812|||”][vc_column_text]March 1990

Artist Jane Zweig discovers books burned in Boston and looks at how Romeo and Juliet has been censored in America.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94784″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532458″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censoring Shakespeare” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532458|||”][vc_column_text]September 1975

A Lithuanian stage producer was dismissed from his post after sending an ‘open letter’ to Soviet authorities protesting censorship in theatre.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93836″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228508533832″][vc_custom_heading text=”Clampdown on drama” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228508533832|||”][vc_column_text]November 2007

Livingstone Njomo Waidhura reports on drama taught in schools and whether Shakespeare is a suitable hero for Kenya. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2016 Index on Censorship magazine celebrates the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death, looking at how his plays have been used around the world to sneak past censors or take on the authorities – often without them realising. Our special report explores how different countries use different plays to tackle difficult themes.

With: Jan Fox, György Spiró, Martin Rowson[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”86201″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/02/staging-shakespearean-dissent/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]