14 May 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

Tony Blair’s former spin doctor has defended the Labour party’s dealings with Rupert Murdoch.

Recalled to the Leveson Inquiry to discuss relations between the press and politicians during his time at Number 10, Alastair Campbell said that the News Corp boss was “certainly the most important media player, without a doubt”.

The Murdoch-owned Sun famously switched its political allegiance and backed Labour in the 1997 general election, which the party won in a landslide victory.

Approaching Murdoch titles as well as the press more generally was part of a New Labour “neutralisation” strategy, Campbell said, to ensure the party had a level playing field”. He said the Sun was a “significant player” among British newspapers.

Campbell, arguably Britain’s most iconic spin doctor, was Tony Blair’s spokesman when he became Labour party leader in 1994 and went on to be Downing Street press secretary and director of communications after the party came to power.

He asserted that Labour did not win because of Murdoch’s support, but rather the media mogul supported the party “because we were going to win”. Campbell refuted the idea of the perceived power of newspapers being key to winning an election, noting that current prime minister had press backing and failed to win a majority in 2010.

Campbell said he had no evidence to suggest there had been a deal between Blair and Murdoch to support New Labour, and also downplayed the three phone calls between them in the eight days prior to the Iraq war in 2003.

He also sought to downplay the influence of spin — “journalists aren’t stupid and the public aren’t stupid,” he said — and claimed that politicians, rather than newspapers, held real power.

He conceded that the New Labour approach to the media (former prime minister Blair famously dubbed the press “feral beasts”) may have given newspapers “too much of a sense of their own power”.

During his previous appearance at the Inquiry in November, Campbell slammed the British press as “putrid”, and singled out the Daily Mail as perpetuating a “culture of hate” for its crime and health scares.

Campbell was not optimistic about the appetite for change in Westminster. “I don’t think Cameron particularly wants to have to deal with this [the Inquiry],” he said. “It would be very difficult not to go along with the recommendations [that the Inquiry produces], but I don’t think there is much appetite.” He also suggested a speech made by education secretary Michael Gove which alluded to the possible “chilling effect” of the Inquiry on the press “may be part of a political strategy” to ensure the Conservative party would not lose media support.

Campbell speculated that some of the more negative media coverage Cameron received might be “revenge” for his setting up the Inquiry in the wake of the phone hacking scandal last summer.

Meanwhile he stressed what he saw as the importance of the Inquiry, praising groups such as Hacked Off, Full Fact and the Media Standards Trust as representing “genuine public concern about what the media has become”.

Also giving evidence earlier today was former cabinet secretary Lord O’Donnell, who oversaw the vetting process for David Cameron’s former communications chief, ex-News of the World editor Andy Coulson. O’Donnell said that Coulson had not been subject to rigorous developed vetting (DV) checks upon entering Downing Street in 2010, and instead went through a more rudimentary “security check” process.

O’Donnell confirmed that DV checks would have involved Coulson signing a form that would disclose any shareholdings that might amount to a conflict of interest. During his evidence last week, Coulson told the Inquiry he held shares in News Corp worth £40,000 while working at Number 10, which he had failed to disclose properly.

O’Donnell told the Inquiry that a “form was signed, but it didn’t disclose shareholdings, and it should have done.”

Leveson said it would be worthwhile to compare the vetting process undergone by other media advisers, “only to demonstrate that there isn’t a smoking gun”.

The Inquiry, which is currently examining the relationship between the press and politicians, will continue tomorrow with evidence from Sky News political editor Adam Boulton and Conservative party politician Lord Wakeham.

Follow Index on Censorship’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry on Twitter – @IndexLeveson

14 May 2012 | Uncategorized

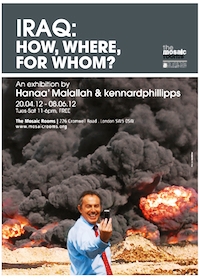

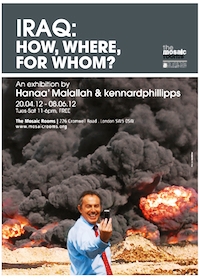

Transport For London has reinstated a banned ad campaign for London’s Mosaic Rooms gallery featuring an image of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair photographing himself on a mobile phone in front of an explosion.

The photomontage “Photo Op”, made in 2005 by kennardphillipps, was promoting a joint show at the gallery for them and Iraqi artist Hanaa’ Malallah called “Iraq: How, Where, For Whom?”

A passenger at Green Park station complained directly to TFL’s commissioner and CBS Outdoor — the company in charge of advertising on the London Underground — was instructed to remove all 100 A3 posters just as they were being put up.

CBS Outdoor claimed the image was in breach of bylaws that prohibit imagery that “contain images or messages that relate to matters of public controversy and sensitivity are of a political nature calling for the support of a particular viewpoint, policy or action or attacking a member of policies of any legislative, central or local government authority [advertisements are acceptable which simply announce the time, date and place of social activities or of a meeting with the names of the speakers and the subjects to be discussed].”

This weekend, when asked about the ban, TFL’s press office claimed no knowledge of it and subsequently issued the following statement:

“Our advertising contractors, CBS Outdoor, were instructed to remove the posters as they depicted a prominent politician during the pre-election period. Should the organisation concerned wish to display the posters again now the election has been held, we would be happy to do so.”

However, nearly two weeks of negotiations between the Mosaic Rooms and CBS Outdoor / TFL had already transpired. This resulted in the creation of an alternate ad campaign design featuring former US President George Bush. When asked if the Mosaic Rooms can now run the entire campaign with the original Blair image, TFL replied “yes.”

Artist Peter Kennard, of kennardphillipps, said at the time of the ban “It seems that for TFL, the Iraq War is not for us to think about and [Tony] Blair is not only beyond criticism, but his actions while he was in office cannot even be acknowledged. What affords him such protection when he is now merely another multi-millionaire businessman amongst many?”

As a charity under the Qattan Foundation, the Mosaic Rooms are entitled to a heavily discounted advertising rate in the London Underground. They contended that their posters asked a question and that TFL’s actions were a “clear act of censorship which removes a poster on purely political grounds while undermining the principles of free artistic expression.”

By saying that the Mosaic Rooms can reinstate the original poster campaign featuring “Photo Op” after banning it on clear political grounds, TFL have shown that they are easily influenced by structures of power. A well-placed passenger with access to the right people in their company can get a campaign taken down — and were the ban not challenged it would have continued. As such, TFL may have set a precedent for other charities and designers seeking to use more political imagery in their work and may think twice before censoring creative expression.

At the time of this writing, CBS Outdoor have still not received instruction from TFL to reinstate the original poster campaign and have proceeded with mounting an alternate image.

25 Apr 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch has told the Leveson Inquiry that Labour leader Gordon Brown “declared war” on News Corp after the Sun moved to back the Conservatives in 2009.

Appearing before the inquiry today, Murdoch described a phone conversation between the pair, during which the veteran newspaper proprietor told the then Prime Minister that the newspaper would be backing a change of government in the next election.

Telling the court that he did not think Brown was in a “very balanced state of mind” during the call, Murdoch explained that the politician had called on the day of his party conference speech in 2009 after hearing about the paper’s altered political allegiance.

Murdoch said: “Mr Brown did call me and said ‘Rupert, do you know what’s going on here?’ I said ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘Well the Sun and what it’s doing.’ I said ‘I’m sorry to tell you Gordon, but we will support a change of government when there’s an election.’”

Despite suggestions from former Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie that Brown “roared” at Murdoch for 20 minutes, Murdoch insisted that there were no raised voices during the conversation.

Describing his relationship with Brown to the court, Murdoch said: “My personal relationship with Brown was always warm — before he became Prime Minister and after. I regret that after the Sun came at him, that’s not so true but I only hope that can be repaired.”

But Murdoch added that Brown made a “totally outrageous statement” when he described News Corp as a “criminal organisation,” after alleging that his health records had been hacked.

“He said that we had hacked into his personal medical records when knew very well how the Sun had found out about his son which was very sad”, Murdoch told the court, who went on to explain that the story relating to Brown’s son’s Cystic Fibrosis had been obtained from a father in a similar situation.

To allegations that he traded favours with Tony Blair, Murdoch repeatedly denied the suggestion: “You are making inferences. I never asked Mr Blair for anything, and neither did I receive anything.”

The court heard that Murdoch was slow to endorse the Labour party in 1994, but he denied that that was part of a strategy to gauge commercial interests. Later in his testimony, somewhat losing his patience, Murdoch added to Robert Jay, QC: “I don’t know how many times I have to state to you Mr Jay, that I never let commercial considerations get in the way.”

After a 1994 dinner with Blair, Murdoch acknowledged that he may have said “He says all the right things but we’re not letting our pants down just yet”, but could not remember exactly.

Similarly, Murdoch did not recall speculating on the future of his relationship with Blair, when he reportedly said: “If our flirtation is ever consummated Tony we will make love like porcupines — very, very carefully.”

Turning to his relationship with David Cameron, Murdoch denied saying he “didn’t think much” of the Conservative party leader. He recalled meeting him at a family picnic at his daughter’s house, and was “extremely impressed by the kindness and feeling he showed to his children”.

When asked if he discussed issues such as broadcast regulation, BBC license fees or Ofcom, Murdoch denied the allegations. He said: “You keep inferring that endorsements were motivated by business motives. If that were the case we would always have supported the Tories, because they’re always more pro-business.”

Jay asked if he and Cameron discussed the appointment of ex-News of the World editor Andy Coulson as spin doctor for the Conservative party. Murdoch explained to the court that he “was as surprised as everybody else” by the appointment.

Murdoch denied rumours that he hadn’t forgiven David Cameron for calling the inquiry, explaining that the state of media in the UK is of “absolutely vital interest to all it’s citizens”, and adding that he welcomed the opportunity to appear before the court because he “wanted to put certain myths to bed.”

The billionaire newspaper owner was also asked about his relationships with numerous other politicians, including Scottish politician Alex Salmond and former Prime Minister John Major. Murdoch also told the court that he “remained a great admirer” of Margaret Thatcher, but denied that he was “one of the main powers behind the Thatcher throne.”

Murdoch echoes his son James’ testimony, saying that relationships between the media and politicans were “part of the democratic process”. He added: “Politicians go out of their way to impress people in the press. All politicians of all sides like to have their views known by the editors and publishers of newspapers, hoping they will be put across, hoping they will succeed in impressing people. That’s the game.”

At the start of today’s hearing, Lord Justice Leveson responded to the furore relating to emails from Jeremy Hunt revealed during James Murdoch’s testimony to the court yesterday.

“I am acutely aware from considerable experience that documents such as these cannot always be taken at face value and can frequently bare more than one evaluation. I am not taking sides or expressing opinion but it is very important to hear every side of the story. In due course we will hear all relevant evidence from all relevant people.”

Rupert Murdoch’s evidence to the inquiry will continue at 10am tomorrow.

Follow Index’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry @IndexLeveson

20 Jan 2011 | News and features

Tony Blair’s appearance at the Iraq inquiry is a test of the competing principles of free expression and confidentiality. John Kampfner asks who should decide what the public hears?

Tony Blair’s appearance at the Iraq inquiry is a test of the competing principles of free expression and confidentiality. John Kampfner asks who should decide what the public hears?

Tony Blair would not appreciate being likened to Julian Assange. The feeling would, I am sure, be entirely mutual. Yet there is a link of sorts between these two figures, so controversial in their very different ways. It revolves around the notion of confidentiality.

The lead-up to the former prime minister’s second appearance before the Iraq enquiry has been dominated by the issue of private correspondence. The refusal by the cabinet secretary, Sir Gus O’Donnell, to accede to the request of the committee chairman, Sir John Chilcot, to release the full musings of Blair and ex-president George Bush is based around a question similar to the one relating to the industrial dumping of US State Department documents. When are the musings of individual officials or politicians public documents and when are they private?

In both cases the competing principles of free expression and confidence stumble on each other, head to head. Assange and his allies argue their case mainly around public interest. The world, he insists, should know all the dirty deeds of dastardly diplomats. A more convincing argument in his favour might be that no serious organisation could remotely hope to keep a single email secret if circulated to 2.5m people, as was apparently the case with the US diplomatic service.

As for the Blair/Bush love-in, the case for secrecy is undermined by Blair’s own decision to publish some of the discussions in his memoirs. Furthermore, written memos between world leaders could surely not qualify as “private”. Telephone calls, presumably yes, but not the written word.

As the Daily Telegraph commented in a leader article this week:

The public deserves to get the fullest possible account of why this country went to war on the basis of what turned out to be misleading intelligence. For many, this remains the rawest of issues; if we are ever to put it behind us, the inquiry must be seen to be as thorough and open as possible. Reaching sensible conclusions almost eight years after the invasion began will be difficult enough without the inquiry being fettered in this way.

In the spirit, we are sure, of free expression, a furious Chilcot decided to publish his exchange of letters with O’Donnell. The committee chairman suggests, in quintessential mandarin style, that he would be “disappointed” if Blair proved less forthcoming in his evidence than in his book.

Otherwise, the Telegraph concludes, “it will appear that Mr Blair is happy to breach the confidentiality of office for a lucrative book deal, but not to inform the British public of the process that led him to send our troops to war”.

John Kampfner is the chief executive of Index on Censorship

Tony Blair’s appearance at the Iraq inquiry is a test of the competing principles of free expression and confidentiality. John Kampfner asks who should decide what the public hears?

Tony Blair’s appearance at the Iraq inquiry is a test of the competing principles of free expression and confidentiality. John Kampfner asks who should decide what the public hears?