7 Feb 2017 | Awards, News, Press Releases

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

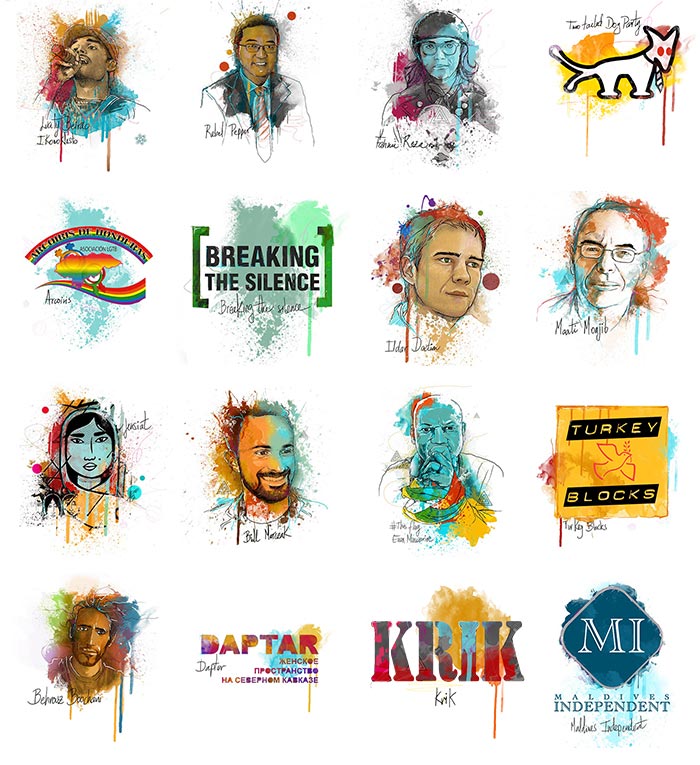

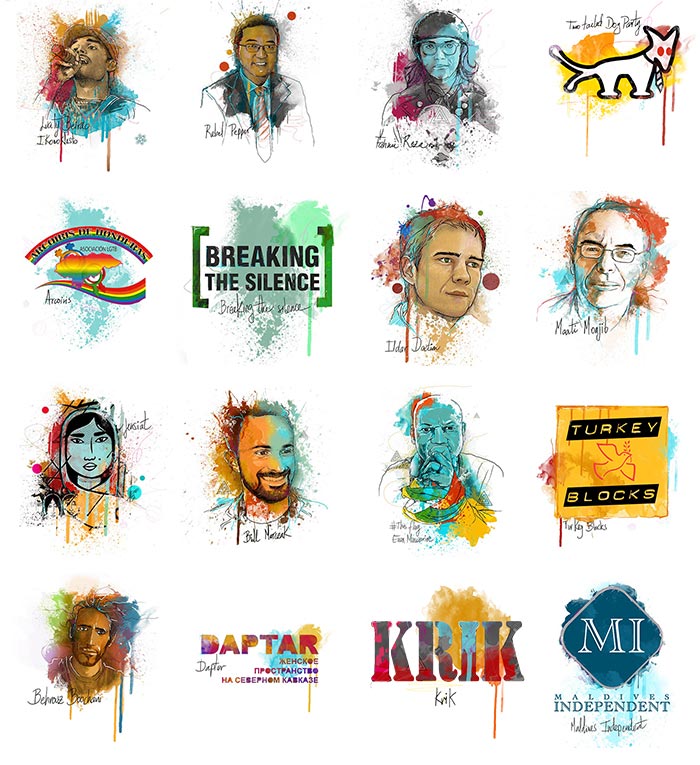

- Sixteen courageous individuals and organisations who fight for freedom of expression in every part of the world

A Zimbabwean pastor who was arrested by authorities last week for his #ThisFlag campaign, an Iranian Kurdish journalist covering his life as an interned Australian asylum seeker, one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists, and an imprisoned Russian human rights activist are among those shortlisted for the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“The creativity and bravery of the shortlist nominees in challenging restrictions on freedom of expression reminds us that a small act — from a picture to a poem — can have a big impact. Our nominees have faced severe penalties for standing up for their beliefs. These awards recognise their courage and commitment to free speech,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include Pastor Evan Mawarire whose frustration with Zimbabwe’s government led him to the #ThisFlag campaign; Behrouz Boochani, an Iranian Kurdish journalist who documents the life of indefinitely-interned Australian asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea; China’s Wang Liming, better known as Rebel Pepper, a political cartoonist who lampoons the country’s leaders; Ildar Dadin, an imprisoned Russian opposition activist, who became the first person convicted under the country’s public assembly law; Daptar, a Dagestani initiative tackling women’s issues like female genital mutilation that are rarely discussed publicly in the country; and Serbia’s Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), which was founded by a group of journalists to combat pervasive corruption and organised crime.

Other nominees include Hungary’s Two-tail Dog Party, a group of satirists who parody the country’s political discourse; Honduran LGBT rights organisation Arcoiris, which has had six activists murdered in the past year for providing support to the LGBT community and lobbying the country’s government; Luaty Beirão, a rapper from Angola, who uses his music to unmask the country’s political corruption; and Maldives Independent, a website involved in revealing endemic corruption at the highest levels in the country despite repeated intimidation.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 17th year, are Harry Potter actor Noma Dumezweni, Hillsborough lawyer Caiolfhionn Gallagher, former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown, designer Anab Jain and music producer Stephen Budd.

Dumezweni, who plays Hermione in the stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, was shortlisted earlier this year for an Evening Standard Theatre Award for Best Actress. Speaking about the importance of the Index Awards she said: “Freedom of expression is essential to help challenge our perception of the world”.

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“The GreatFire team works anonymously and independently but after we were awarded a fellowship from Index it felt like we had real world colleagues. Index helped us make improvements to our overall operations, consulted with us on strategy and were always there for us, through the good times and the pain,” Charlie Smith of GreatFire, 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards Digital Activism Fellow.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Vodafone, media partner CNN, VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers, Psiphon and Gorkana. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

- Index on Censorship is a UK-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide.

- More detail about each of the nominees is included below.

- The winners will be announced at a ceremony at The Unicorn Theatre, London, on 19 April.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact: Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected]. More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2017.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards nominees 2017

Arts

Luaty Beirão, Angola

Rapper Luaty Beirão, also known as Ikonoklasta, has been instrumental in showing the world the hidden face of Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos’s rule. For his activism Beirão has been beaten up, had drugs planted on him and, in June 2015, was arrested alongside 14 other people planning to attend a meeting to discuss a book on non-violent resistance. Since being released in 2016, Beirão has been undeterred attempting to stage concerts that the authorities have refused to license and publishing a book about his captivity entitled “I Was Freer Then”, claiming “I would rather be in jail than in a state of fake freedom where I have to self-censor”.

Rebel Pepper, China

Wang Liming, better known under the pseudonym Rebel Pepper, is one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists. For satirising Chinese Premier Xi Jinping and lampooning the ruling Communist Party, Rebel Pepper has been repeatedly persecuted. In 2014, he was forced to remain in Japan, where he was on holiday, after serious threats against him were posted on government-sanctioned forums. The Chinese state has since disconnected him from his fan base by repeatedly deleting his social media accounts, he alleges his conversations with friends and family are under state surveillance, and self-imposed exile has made him isolated, bringing significant financial struggles. Nonetheless, Rebel Pepper keeps drawing, ferociously criticising the Chinese regime.

Fahmi Reza, Malaysia

On 30 January 2016, Malaysian graphic designer Fahmi Reza posted an image online of Prime Minister Najib Razak in evil clown make-up. From T-shirts to protest placards, and graffiti on streets to a sizeable public sticker campaign, the image and its accompanying anti-sedition law slogan #KitaSemuaPenghasut (“we are all seditious”) rapidly evolved into a powerful symbol of resistance against a government seen as increasingly corrupt and authoritarian. Despite the authorities’ attempts to silence Reza, who was banned from travel and has since been detained and charged on two separate counts under Malaysia’s Communications and Multimedia Act, he has refused to back down.

Two-tailed Dog Party, Hungary

A group of satirists and pranksters who parody political discourse in Hungary with artistic stunts and creative campaigns, the Two-tailed Dog Party have become a vital alternative voice following the rise of the national conservative government led by Viktor Orban. When Orban introduced a national consultation on immigration and terrorism in 2015, and plastered cities with anti-immigrant billboards, the party launched their own mock questionnaires and a popular satirical billboard campaign denouncing the government’s fear-mongering tactics. Relentlessly attempting to reinvigorate public debate and draw attention to under-covered or taboo topics, the party’s efforts include recently painting broken pavement to draw attention to a lack of public funding.

Campaigning

Arcoiris, Honduras

Arcoiris, Honduras

Established in 2003, LGBT organisation Arcoiris, meaning ‘rainbow’, works on all levels of Honduran society to advance LGBT rights. Honduras has seen an explosion in levels of homophobic violence since a military coup in 2009. Working against this tide, Arcoiris provide support to LGBT victims of violence, run awareness initiatives, promote HIV prevention programmes and directly lobby the Honduran government and police force. From public marches to alternative awards ceremonies, their tactics are diverse and often inventive. Between June 2015 and March 2016, six members of Arcoiris were killed for this work. Many others have faced intimidation, harassment and physical attacks. Some have had to leave the country because of threats they were receiving.

Breaking the Silence, Israel

Breaking the Silence, an Israeli organisation consisting of ex-Israeli military conscripts, aims to collect and share testimonies about the realities of military operations in the Occupied Territories. Since 2004, the group has collected over 1,000 (mainly anonymous) statements from Israelis who have served their military duty in the West Bank and Gaza. For publishing these frank accounts the organisation has repeatedly come under fire from the Israeli government. In 2016 the pressure on the organisation became particularly pointed and personal, with state-sponsored legal challenges, denunciations from the Israeli cabinet, physical attacks on staff members and damages to property. Led by Israeli politicians including the prime minister, and defence minister, there have been persistent attempts to force the organisation to identify a soldier whose anonymous testimony was part of a publication raising suspicions of war crimes in Gaza. Losing the case would set a precedent that would make it almost impossible for Breaking the Silence to operate in the future. The government has also recently enacted a law that would bar the organisation’s widely acclaimed high school education programme.

Ildar Dadin, Russia

A long-term opposition and LGBT rights activist, Ildar Dadin was the first, and remains the only, person to be convicted under Russia’s 2014 public assembly law that prohibits the “repeated violation of the order of organising or holding meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches or picketing”. Attempting to circumvent this restrictive law, Dadin held a series of one-man pickets against human rights abuses – an enterprise for which he was arrested and sentenced to three years imprisonment in 2015. In November 2016, website Meduza published a letter smuggled to his wife in which Dadin wrote that he was being tortured and abuse was endemic in Russian jails. The letter, a brave move for a serving prisoner, had wide resonance, prompting a reaction from the government and an investigation. Against his will, Dadin was transferred and disappeared within the Russian prison system until a wave of public protest led to his location being revealed in January 2017. Dadin was released on February 26 after a supreme court order.

Maati Monjib, Morocco

A well-known academic who teaches African studies and political history at the University of Rabat since returning from exile, Maati Monjib co-founded Freedom Now, a coalition of Moroccan human rights defenders who seek to promote the rights of Moroccan activists and journalists in a country ranked 131 out of 180 on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. His work campaigning for press freedom – including teaching investigative journalism workshops and using of a smartphone app called Story Maker designed to support citizen journalism – has made him a target for the authorities who insist that this work is the exclusive domain of state police. For his persistent efforts, Monjib is currently on trial for “undermining state security” and “receiving foreign funds.”

Digital Activism

Jensiat, Iran

Jensiat, Iran

Despite growing public knowledge of global digital surveillance capabilities and practices, it has often proved hard to attract mainstream public interest in the issue. This continues to be the case in Iran where even with widespread VPN usage, there is little real awareness of digital security threats. With public sexual health awareness equally low, the three people behind Jensiat, an online graphic novel, saw an an opportunity to marry these challenges. Dealing with issues linked to sexuality and cyber security in a way that any Iranian can easily relate to, the webcomic also offers direct access to verified digital security resources. Launched in March 2016, Jensiat has had around 1.2 million unique readers and was rapidly censored by the Iranian government.

Bill Marczak, United States

A schoolboy resident of Bahrain and PhD candidate in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, Bill Marczak co-founded Bahrain Watch in 2013. Seeking to promote effective, accountable and transparent governance, Bahrain Watch works by launching investigations and running campaigns in direct response to social media posts coming from activists on the front line. In this context, Marczak’s personal research has proved highly effective, often identifying new surveillance technologies and targeting new types of information controls that governments are employing to exert control online, both in Bahrain and across the region. In 2016 Marczak investigated several government attempts to track dissidents and journalists, notably identifying a previously unknown weakness in iPhones that had global ramifications.

#ThisFlag and Evan Mawarire, Zimbabwe

In May 2016, Baptist pastor Evan Mawarire unwittingly began the most important protest movement in Zimbabwe’s recent history when he posted a video of himself draped in the Zimbabwean flag, expressing his frustration at the state of the nation. A subsequent series of YouTube videos and the hashtag Mawarire used, #ThisFlag, went viral, sparking protests and a boycott called by Mawarire, which he estimates was attended by over eight million people. A scale of public protest previously inconceivable, the impact was so strong that private possession of Zimbabwe’s national flag has since been banned. The pastor temporarily left the country following death threats and was arrested in early February as he returned to his homeland.

Turkey Blocks, Turkey

In a country marked by increasing authoritarianism, a strident crackdown on press and social media as well as numerous human rights violations, Turkish-British technologist Alp Toker brought together a small team to investigate internet restrictions. Using Raspberry Pi technology they built an open source tool able to reliably monitor and report both internet shut downs and power blackouts in real time. Using their tool, Turkey Blocks have since broken news of 14 mass-censorship incidents during several politically significant events in 2016. The tool has proved so successful that it has begun to be implemented elsewhere globally.

Journalism

Behrouz Boochani, Manus Island, Papua New Guinea/Australia (he is an Iranian refugee)

Iranian Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani fled the city of Ilam in Iran in May 2013 after the police raided the Kurdish cultural heritage magazine he had co-founded, arresting 11 of his colleagues. He travelled to Australia by boat, intending to claim asylum, but less than a month after arriving he was forcibly relocated to a “refugee processing centre” in Papua New Guinea that had been newly opened. Imprisoned alongside nearly 1000 men who have been ordered to claim asylum in Papua New Guinea or return home, Boochani has been passionately documenting their life in detention ever since. Publicly advertised by the Australian Government as a refugee deterrent, life in the detention centre is harsh. For the first 2 years, Boochani wrote under a pseudonym. Until 2016 he circumvented a ban on mobile phones by trading personal items including his shoes with local residents. And while outside journalists are barred, Boochani has refused to be silent, writing numerous stories via Whatsapp and even shooting a feature film with his phone.

Daptar, Dagestan, Russia

In a Russian republic marked by a clash between the rule of law, the weight of traditions, and the growing influence of Islamic fundamentalism, Daptar, a website run by journalists Zakir Magomedov and Svetlana Anokhina, writes about issues affecting women, which are little reported on by other local media. Meaning “diary”, Daptar seeks to promote debate and in 2016 they ran a landmark story about female genital mutilation in Dagestan, which broke the silence surrounding that practice and began a regional and national conversation about FGM. The small team of journalists, working alongside a volunteer lawyer and psychologist, also tries to provide help to the women they are in touch with.

KRIK, Serbia

Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) is a new independent investigative website which was founded by a team of young Serbian journalists intent on exposing organised crime and extortion in their country which is ranked as having widespread corruption by Transparency International. In their first year they have published several high-impact investigations, including forcing Serbia’s prime minister to admit that senior officials had been behind nocturnal demolitions in a Belgrade neighbourhood and revealing meetings between drug barons, the ministry of police and the minister of foreign affairs. KRIK have repeatedly come under attack online and offline for their work –threatened and allegedly under surveillance by state officials, defamed in the pages of local tabloids, and suffering abuse including numerous death threats on social media.

Maldives Independent, Maldives

Website Maldives Independent, which provides news in English, is one of the few remaining independent media outlets in a country that ranks 112 out of 180 countries on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. In August 2016 the Maldives passed a law criminalising defamation and empowering the state to impose heavy fines and shut down media outlets for “defamatory” content. In September, Maldives Independent’s office was violently attacked and later raided by the police, after the release of an Al Jazeera documentary exposing government corruption that contained interviews with editor Zaheena Rasheed, who had to flee for her safety. Despite the pressure, the outlet continues to hold the government to account.

6 Feb 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Three journalists working for Quotidien, a daily current affairs show, were violently ejected from of a conference at Palais des Congrès on 1 February after attempting to ask a question to leader of the National Front party Marine Le Pen, newspaper Libération reported.

Journalist Paul Larrouturou, who had an accreditation allowing him to be present during the Salon des Entrepreneurs, attempted to ask Le Pen about claims she had misused European parliament funds to pay her body guards.

Larrouturou asked Le Pen: “Was your bodyguard really your parliamentary assistant or…”.

The journalist was grabbed from behind before finishing the question. He and two of his colleagues were then prevented from coming back inside by security.

The National Front told French newspaper Le Parisien that it did not take responsibility for the actions of the security guards, saying: “It’s not us. There were no instructions [from us]. We don’t run the Palais.”

However, the journalists said it was a member of Le Pen security who gave the order to expel them.

This is not the first incident where the three journalists encountered problems with the Front National. They were assaulted by Front National supporters during the 1 May 2015 party march.

Turkish journalist Arzu Demir was sentenced to six years in prison on charges of spreading propaganda for a terrorist organisation through two books she has authored, independent news website T24 reported.

The İstanbul 13th High Criminal Court handed down a three year sentence for each book in a trial session held on 26 January.

Demir was being tried on charges of “spreading propaganda for a terrorist organisation,” “praising a crime and a criminal” and “inciting the public to commit a crime” in her books Dağın Kadın Hali, meaning The Female State of the Mountain and Devrimin Rojava Hali, meaning The Rojava State of Revolution.

Dağın Kadın Hali features interviews with 11 women who are Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) fighters, which is considered a terrorist organisation by the Turkish government. A Turkish court had banned the book and ordered it to be pulled from bookstore shelves on 15 March 2016.

The Rojava State of Revolution, banned in April 2016, investigates the current attempts to rebuild in the Syrian Kurdish city of Rojava.

In an interview with independent news website Bianet, Arzu Demir said: “I have always said, since the start of these trials, that the case is a political trial based on the current conditions. This ruling is proof of that. All I did, as I said in my statement, was journalism.”

“I am glad that I’ve written [these books] and I am continuing to write,” she added.

The court did not introduce any possible reductions to the journalist’s sentence on the grounds that she had shown “no regret” for the alleged crime.

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) raided the flat of former editor-in-chief of Vesti.Reporter magazine, Inna Zolotukhina, in Kharkiv around 7.30 AM on 27 January, Detector Media reported.

“I opened the door and a crowd of men entered the apartment. There were seven people, three of them from Kyiv’s Security Service of Ukraine, two from Kharkiv’s Security Service of Ukraine and two witnesses”, Zolotukhina told Detector Media.

At the same time, another search was conducted at the journalist’s mother’s house in Brovary near Kyiv.

Later Zolotukhina wrote on her Facebook page that she had been interrogated by the SBU as a witness on 30 January. According to the journalist, the questioning lasted from 10.00 to 18.30.

“I have signed a non-disclosure agreement, so now I can’t say anything”, the journalist wrote.

The search and interrogation were linked to a criminal case on separatism brought against unidentified persons at Media Invest Group holding which publishes Vesti Newspaper and Vesti.Reporter Magazine. Many journalists and employees of the holding have been interrogated in connection to the case.

On 25 January a court in Baku sentenced journalist Fuad Gahramanli to 10 years in prison, Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety reported.

The case is related to the armed incident between religious group, Muslim Union Movement, and police officers in the village of Nardaran where six people died, including two police officers.

Fuad Gahramanli is not a member of the religious group but was accused of promoting them on Facebook, where he urged people not to abandon the MUM’s leader and to continue protesting, IRFS reported.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jan 2017 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text] Turkey’s state of emergency, announced after July’s coup attempt, was extended for three months in January. While new executive orders continue to increase the repression of opposition journalists, academics, trade unionists, performers and institutions, parliament is discussing changes to the constitution that have been described as a “regime change”. As in the past, the state of emergency has hit Kurdish-populated regions hardest.

Turkey’s state of emergency, announced after July’s coup attempt, was extended for three months in January. While new executive orders continue to increase the repression of opposition journalists, academics, trade unionists, performers and institutions, parliament is discussing changes to the constitution that have been described as a “regime change”. As in the past, the state of emergency has hit Kurdish-populated regions hardest.

The Amed Film Festival was held jointly by the Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality Culture and Art Directorate and the Middle East Cinema Academy Association (OSAD) in 2012. The objective of the festival was to introduce viewers to films created in the Middle East in all languages of the peoples of the region, with a special emphasis on Kurdish filmmakers, and to contribute to film production. The festival also aimed to “provide the groundwork for filmmakers to be able to express themselves on a free platform”. The second festival, planned for November 2016 under the slogan “Unlimited Cinema”, could not be mounted due to the appointment of a trustee to run the Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality and the arrest of its co-mayors, who were members of the pro-Kurdish HDP. Or rather, the festival committee asserted that trustee mayoralties were illegitimate due to “intervention in the people’s will” and decided not to work with the trustee.

In any case, it was unlikely that the trustee mayoralty would have allowed the festival to use any of the venues under its administration. Festival organisers made a call for solidarity to local and international festivals, asking them to show their films between 22-25 December, as “the duty of art and artists under these conditions is not to shrink away, but to raise their voices to explain the reality of the times”.

The festival’s films were shown in Diyarbakır, Istanbul, Van, Batman, Cyprus and Italy. They were put on in trade associations, trade unions and other associations in Diyarbakır (Pir Sultan Abdul Cultural Association and Cemevi, TMMOB, and Eğitim Sen), at the Batman Culture and Art Association in Batman, at the Cyprus Üretim Sokağı Cultural Centre in Cyprus, and at the Mezopotamya Cinema and contemporary arts centre Depo in Istanbul. The Italian leg was organised by Gianluca Peciola from the Left Ecology Freedom Party.

Peciola had been behind the successful initiative to twin Rome’s mayoralty with Kobane in 2015, and he expressed his solidarity with the festival: “There is heavy repression in Turkey, especially in the cultural and artistic fields. We are in solidarity with Kurdish artists and the Kurdish people, whose cultural values and cultural works are being repressed in Kurdistan. We want to demonstrate this solidarity through this work.”

The festival had planned to screen 90 films but it was only able to show 45. However, the call for solidarity and the responses to that call created a positive atmosphere. In Diyarbakır alone, 2,000 people watched the films.

Director Zeynel Doğan, who sits on the festival committee, said that the festival had been stronger before, having been weakened when it lost its support. Despite this Doğan said its “energy had increased”.

Amed Theatre Festival, which had been organised by Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre shortly before the film festival, experienced similar issues.

After the trustee was appointed to the mayoralty, the Amed Theatre Festival was cancelled. Subsequently, 10 theatre groups from Turkey and Europe that were going to be part of the festival performed on their own stages between 21 November and 5 December in support of the festival, under the slogan “We are the reality, you are playing with reality”.

MKM Teatra Jiyana Nû, a troupe who perform in Kurdish, explained its solidarity with the festival: “The issue here isn’t merely that a festival is not taking place, the issue is that the breath that society is able to take thanks to art is being allowed to be stifled. We do not want that breath to be stifled, and even if the Amed Festival cannot physically take place in Amed [Diyarbakır], we say ‘Amed Theatre Festival is everywhere’ in the belief that one day it will definitely once again be held there.”

It is worth also noting that no large festival in Istanbul has responded to the Amed Festival’s call for solidarity: from the perspective of the Istanbul festivals, it is becoming much more difficult for regional festivals to stand in solidarity with one another.

“Cutting off the breath of society” is a good description of the repression being carried out in the Kurdish region. Fifty-two of the 106 pro-Kurdish mayoralties have had trustees appointed to them, and 76 co-mayors are under arrest on the grounds of “supporting terror organisations”. The state of emergency Executive Order Regarding the Taking of Certain Precautions shut down dozens of associations in the region. The cultural and artistic divisions of municipalities in the region are being rendered non-functional.

All the actors in the Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which creates and puts on plays in Kurdish, have been fired. From the time pro-Kurdish parties began to take over municipalities in 1999, there was a big revival in cultural and artistic life in Turkey’s Kurdish provinces. New venues opened, regular audiences began to attend events and workshops held by these venues integrated the young people of the region into the artistic environment. Even during the peace process, these institutions were under surveillance, but despite these conditions, they made an important contribution to the protection and development of Kurdish language and culture, its use as a language of artistic production and its institutionalisation.

The dismantlement of artistic groups working at venues such as theatres under municipality control, the Cegerxwin Cultural Centre and the Amed Art Gallery is a sign that from now on these spaces are only to be used in ways that suit the political and cultural agenda of the new municipal administration.

In a funny sense, the way in which the Amed film and theatre festivals were left without support or venues after refusing to work with the trustee has led actors in Diyarbakır’s cultural and artistic world to critically evaluate their own practices. Artistic institutions that had been able to create and prosper for years thanks to the opportunities provided by municipal administrations saw this as an opportunity for cooperation with local organisations and to form an independent model of production and circulation. This also opened the way for certain ideas which had been considered before, such as travelling festivals, to be put into practice. According to filmmaker and OSAD board member İlham Bakır, another example of a future intention now being put into practice thanks to the de facto predicament of the festival was an independent structure to show films over a wider geographical area in cooperation with other institutions.

Filmmakers from the region, as part of the work aiming to restructure the Kurdish movement along egalitarian and democratic lines in political and social life, have long considered the questions of how a democratic cinematic production and distribution model can be put into place and whether a cinematic fund could be established independently of the government. Indeed, they have even invited a group of filmmakers from Istanbul to discuss the idea of a cinematic commune.

Both festivals are preparing to open their own venues in order to continue working independently.

Meanwhile, as artistic groups are no longer be able to benefit from the political advantages the Kurdish movement provided in the region, the idea of a commune has gaining traction.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485772040601-4013dd52-0984-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Jan 2017 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/LzWBgzJrQdo”][vc_column_text]As tens of thousands of women took to the streets around the world on 21 January, another woman, the Turkish MP Şafak Pavey was being treated in hospital for injuries sustained during a physical assault on the floor of the Grand National Assembly during debates on constitutional amendments.

Pavey had just delivered a moving speech in which she warned that the presidential system being considered would bring about unchallenged one-man rule. The “bandits”, as she called them, a group of women MPs belonging to the ruling AKP, attacked her and two other MPs, Aylin Nazlıaka, an independent, and Pervin Buldan from the Kurdish HDP. The AKP MPs were said to be acting under a male colleague’s orders.

The attack contrasted sharply with the pictures of enthusiastic women from around the United States and the world committed to sisterhood and equality. The distance between the two extremes might seem to be yawning but isn’t. In Turkey, the gap opened up in just four short years.

The empowered mood created by women marching for equal rights and uniting their voices in opposition reminded me of the heady days of 2013 when the anti-government Gezi Park protests rocked Turkey. Like the demonstrators in DC and London, people all over Turkey took to the streets to raise a chant against our own Trump: President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In Gezi, the seeds of dissent spread through social media and bloomed across the country just as the women’s march did across the globe. It was just the beginning, or so we thought.

After a brutal suppression that left at least 10 dead and over 8,000 injured, the Gezi spirit, that united voice, faded away. The most significant political heritage was the “Vote and Beyond” organisation, which launched an incredibly effective election monitoring network during the June 2015 elections. Thanks to that group and the popular young Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtaş’s energy, the outcome of the polls reflected the full and complete picture of Turkey’s population in parliament. The combined opposition parties were the majority in the assembly and to continue governing, the AKP would be forced to form a coalition. Then things happened.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”85130″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]As the ceasefire with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) collapsed and armed conflict resumed, coalition negotiations ground into political deadlock as the summer wore on. Erdogan called a snap election for that November that lined up with his political ambitions. Less than a month before the election, a staggering terror attack rocked Ankara and ongoing deaths of security personnel in the country’s south-east added to a grim mood. At the polls, the AKP regained its majority in parliament. Though the governing party was nominally back in full control, it lacked political legitimacy and popular support, both of which would be delivered by the rogue military units that staged the failed July 15 coup and paved the way for Erdogan’s emergency rule.

Witch hunts are a strange thing. Even if you spot one when it’s getting underway, it’s always too late to stop it.

After the election, the political opposition was locked out of enacting change through parliament. It was further paralysed by Erdogan’s “shock and awe” tactics, which saw the leaders of the parties assaulted on the floor of the assembly or imprisoned on fabricated terror charges. Opposition voters are too depressed now to remember the confident and exhilarating days of the Gezi protests.

It would be a mistake to dismiss Turkey’s experience as a unique case. There are parallels with the unfolding situations in Russia, Poland, Hungary and now the USA. The bullies of our interesting times are singing from the same hymn sheet, using identical language and narratives — power to the right people, experts and intellectuals are overrated, overturn the establishment. The forces of resistance must now share strategies as well. Opposition to the growing threat of illiberal democracy needs to network and be vocal or else our initial responses to the horrors and human rights violations — including the purge of Turkey’s press under emergency rule — would be a waste of time.

Here’s a small taste of where we failed in Turkey — a warning to Europeans and Americans of what not to do.

“No” is an intoxicating word that gives emotional fuel to the masses. After swimming in the slack waters of identity politics or concerning yourself with whether or not your avocados are fair trade, taking to the streets en masse for a proper cause is like a fresh breeze. But as we learned in Turkey, “No” can also be a dead end. It exists in a dangerous dependency on the what those in power are up to. It shouldn’t be mistaken for action as it is only a reaction.

“No” is unable to create a new political choice. It is an anger game that sooner or later will exhaust all opposition by splitting itself into innumerable causes intent on becoming an individual obstacle to the ruling power.

Make no mistake: the bullies of the world are united in a truly global movement. It is sweeping all before it. And it’s not just Putin, Trump, Erdogan or even Orban, it’s their minions, millions of fabricated apparatchiks that invade the political, social and digital spheres like multiplying gremlins.

What the opposition must do — what Turkey’s protesters failed to do — is strengthen the infrastructure, harden networks and open strong lines of communication between disparate groups whether at home or abroad. All those lefty student movements, marginalised progressive newspapers or resisting communities that are labelled as naïve or passé until now must coalesce around core campaigns and goals.

Failure to move beyond “No”, in Turkey’s case, has made alternative and potential political movements all but invisible. There are just three leftist newspapers in Turkey, three ghosts to break news about women MPs being beaten up. And that’s because we can’t move past “No” when others were shut down or silenced.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485771885900-d32a2643-5934-8″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Arcoiris, Honduras

Arcoiris, Honduras Jensiat, Iran

Jensiat, Iran

Turkey’s state of emergency, announced after July’s coup attempt, was extended for three months in January. While new executive orders continue to increase the repression of opposition journalists, academics, trade unionists, performers and institutions, parliament is discussing changes to the constitution that have been described as a “regime change”. As in the past, the state of emergency has hit Kurdish-populated regions hardest.

Turkey’s state of emergency, announced after July’s coup attempt, was extended for three months in January. While new executive orders continue to increase the repression of opposition journalists, academics, trade unionists, performers and institutions, parliament is discussing changes to the constitution that have been described as a “regime change”. As in the past, the state of emergency has hit Kurdish-populated regions hardest.