3 Mar 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Russia, Ukraine

(Image: @ilya_shepelin/Twitter)

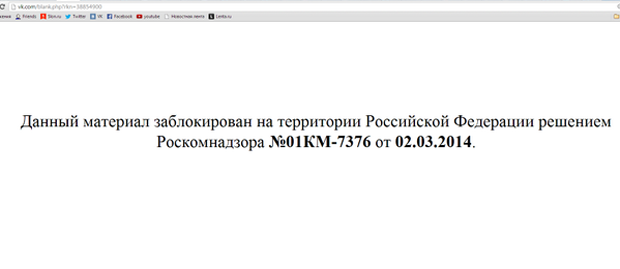

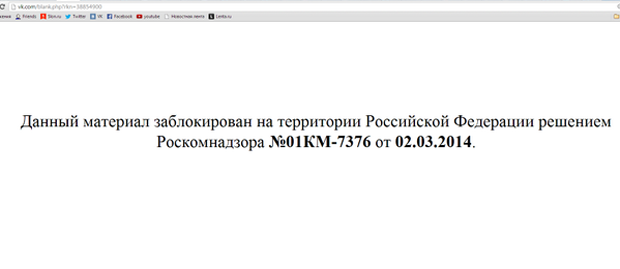

Russian authorities have blocked access to 13 sites connected to “Ukrainian nationalist organisations” on the social media site Vkontakte, Russia’s answer to Facebook.

The Russian General Prosecutor’s Office requested that Roskomnadzor — the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media — block the pages, the body said in a statement Monday. The pages promoted Ukrainian nationalist groups and “contained direct appeals to Russian people to conduct terrorist activities,” the statement read.

There had been reports over the weekend of pages on Vkontakte being blocked, but the message from Roskomnadzor confirms this.

While it is unclear which sites the ban covers, it appears a group connected to the Euromaidan protests is one of them. A screen grab, allegedly from a Euromaidan group, first shared by a journalist from Russian news site slon.ru, read: “This material was blocked on the territory of Russian Federation by a decision by the State Communication Committee” and that the decision had been made on 2 March.

This article was posted on March 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Feb 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Russia

(Image: Gonçalo Silva/Demotix)

The Sochi Winter Olympics opening ceremony is taking place today, and organisers have declared that a record 65 world leaders are attending. But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. As it turns out, some of the biggest names in global politics will not be in the stands cheer on their athletes as the games are officially kick off. Indeed, quite a few won’t be taking the trip to Sochi at all. Barack Obama is sending a delegation including openly gay figure skater Brian Boitano in his place, and Angela Merkel, David Cameron and Francois Hollande are also staying away.

But while the International Olympic Committee’s Thomas Bach was less than impressed by the apparent boycott, labelling it an “ostentatious gesture” that “costs nothing but makes international headlines”, the absence of the big guns does give the lesser-known world leaders a chance to shine. Not all guests have been confirmed, but we’ve got the low-down on some of the the leaders the cameras might pan to during today’s festivities, or who could be spotted in the slopes over the coming weeks.

Alexander Lukashenko

(Image: Ivan Uralsky/Demotix)

Putin’s long time colleague and fellow ice hockey enthusiast surely wouldn’t miss the Winter Olympics for the world. The Belarusian president is known as “the last dictator in Europe”, his near 20 years in power having passed without a single free and fair election. Under his leadership, peaceful protests have been violently dispersed, and civil society activists and political opposition — including rival candidates from the 2010 presidential elections — have been jailed. A brand new report from Index also concludes that: “Belarus continues to have one of the most restrictive and hostile media environments in Europe.”

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

(Image: Philip Janek / Demotix)

The Turkish president made global headlines last summer, over his regime’s violent crackdown on the peaceful Gezi park demonstrations. Rather than accepting the protests were a manifestation of genuine grievances by his people, he blamed “foreign hands” and their “domestic collaborators” like many a less-than-democratic leader before him. His government was recently implicated in a big corruption scandal, and only yesterday, parliament approved controversial amendments to the country’s internet law. The new law, opposed by civil society, the opposition and international organisations alike, gives the government wide-reaching powers over the internet, effectively allowing them to block websites without court rulings, and gives them access to user data.

Viktor Yanukovych

(Image: Oleksandr Nazarov/Demotix)

The Ukrainian president’s failure to sign a treaty securing closer ties with the EU in November, sparked the country’s ongoing Euromaidan protests. The authorities response was heavy handed — police clashed with demonstrators and journalist were targeted, leading to international condemnation. They authorities even briefly implemented a highly repressive new law, among other things allowing security services to monitor the internet, and defining NGOs receiving funding from abroad as “foreign agents”. The law was, however, scrapped only days later following outrage from civil society. Meanwhile,Ukraine’s Prime Minister and government also stepped down, while Yanukovych took four days off ill. He’s back in the office now — just in time head to Sochi for a much-hyped meeting with Putin.

Nursultan Nazarbayev

(Image: Vladimir Tretyakov/Demotix)

Kazakhstan’s president has been in power since 1991, and during that time, allegations of human rights abuses, including attacks on demonstrators and independent media, as well as widespread corruption have been regularly levelled at him. In 2012, following clashed between the police and striking workers, the president, who already effectively controls the legislature and the judiciary, further extended his emergency powers. But Putin wouldn’t even be his only high-flying friend. In September, Kanye West performed at his grandson’s wedding. The reported price tag? $3 million. Did I mention the accusations of corruption? Meanwhile, former British prime minister Tony Blair spent two years advising Nazarbayev and his government on democracy and good governance — a deal which “produced no change for the better or advance of democratic rights in the authoritarian nation”.

Emomali Rahmon

(Image: Riccardo Valsecchi/Demotix)

He has been the head of the government of Tajikistan since 1992, and was in power during the country’s civil war, where 100,000 people lost their lives. Allegations of human rights abuses, including torture by security forces and arbitrary arrests, are widespread. Much of the media is state-controlled, and independent journalists face violence and intimidation. “Publicly insulting the president” can see you jailed for as long as five years. Recently, a prominent member of the opposition, Zaid Saidov, was sentenced to 26 years in prison following what has been described as a “politically motivated trial”. In Sochi, he is set to meet with not only Putin, but also Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

This article was posted on February 7 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Ukraine

This video from YouTube shows a protester abused by police in Kiev.

As the conflict in Kiev continues to unfold, Ukrainian civil society activists tell Index negotiations and urgent reaction of the international community are vital to resolve the crisis.

Severe clashes between the riot police and protesters have led to at least three deaths; two of the protesters were shot with firearms on Wednesday. One more activist was found dead after unidentified people kidnapped and tortured him. Hundreds of protesters were injured as the police used flash grenades and other weapon (along with firearms, as it appeared) against the Euromaidan demonstrators.

The Institute of Mass Information reports at least 42 journalists were injured by the actions of the police.

Index joined 25 other organisations, united in the Civic Solidarity Platform, a coalition of human rights groups from Europe, Asia and North America, in a call for an immediate end to violence and dialogue between the opposing sides, to reach a peaceful resolution to an “acute human dimension crisis in Ukraine.”

“Developments in the situation in Ukraine are critical for the whole post-Soviet history and for the issue of human rights in the OSCE countries. This is why stabilisation of the situation in Ukraine – not in an authoritarian, but in a democratic sense – is crucial for the whole OSCE region,” the joint statement reads.

The protest in Ukraine started last November as it became clear the authorities refused to sign an Association Agreement with the EU.

“Now the protests are not about the European integration. It is all about the right to live in a free country, the right to speak out, to unite and defend our freedoms,” says Maryna Tsapok, an expert from the UMDPL Association, an NGO that monitors the activities of law enforcement.

She refers to a new law adopted in Ukraine on 16 January 2014 that seriously restricts freedoms of expression, assembly and association in the country.

“The authorities say this law and the actions of the police are aimed at restoring of the rule of law. But you cannot restore the rule of law by breaking the Constitution and international treaties. The escalation of the conflict should be stopped immediately by negotiations. But while the government is talking with the opposition, the police continue to use severe force against people in the streets, and the death toll is counting.”

“The authorities of the country have crossed the line,” says Olexandra Matviychuk, the Chair of the Centre for Civic Liberties. “It is almost impossible to predict the development of the situation. But what’s clear is that real and immediate measures from the international community are needed.”

“Serious escalation of the situation in Ukraine is the direct effect of the fact that from the very beginning of the protest movement the government has not taken any single step to build a comprise, but instead made a whole range of steps to suppress the protestors. They include attempts to forcefully disperse peaceful protestors and then to persecute them, violence against journalists, threatening of activists in the regions and, finally, adoption of the draconian legislation curtailing human rights and freedoms in the country,” says Antonina Cherevko, a media lawyer.

She adds: “The Ukrainian issue today can potentially create security problems not only for the country itself, but for the whole region. In this situation, a strong reaction and action from the established democracies is highly needed.”

This article was published on 23 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Ukraine

Clashes in Kiev between police and protesters on 19 January (Image: Julia Kochetova/Demotix)

At least 26 journalists were injured during the clashes between police and protesters in Kiev on 19 and 20 January.

According to the Institute for Mass Information (IMI), most of the reporters were wounded by stun grenades or rubber bullets used by the police while dispersing a rally in central Kiev, in protest at the new repressive legislation adopted in Ukraine last week.

IMI’s reports says the riot police on several occasions particularly targeted journalists, despite them having “Press” signs on their equipment and clothes. For instance, police officers shook a bus, while several journalists were filming the events from its roof, leading to several reporters falling off. The police attacked one of them, Denis Savchenko, a cameraman of 5 Channel. They tore his “press” badge of him and detained him briefly. The reporter now at home, with his leg broken.

Anatoly Lazarenko, a reporter of Spilno.tv online television, was shot in the hand while broadcasting live from the scene of the clashes. The reporter says the police aimed specifically at him to prevent him from reporting.

The legislation, adopted in Ukraine on 16 January 2014, has already been dubbed “the Dictatorship Law” by the country’s civil society. According to legal analysis done by experts of the Centre for Civil Liberties and Euromaidan SOS initiative, the law violates legislative procedures, runs counter to international treaties and domestic legislation and seriously restrict rights and freedoms of Ukrainian citizens.

The new law particularly targets free speech. It criminalises defamation, provides for liability for “distribution of extremist materials” and introduces a requirement for the registration of online media. It is now also forbidden to collect and disseminate information concerning law enforcement officers and judges.

The repressive law was officially signed by the President Yanukovich on 17 January, and has already come into force.

The full text of the independent legal analysis of the human rights related bills, adopted in Ukraine, is available here.

This article was posted on 20 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org