12 Jan 2015 | Events

On the day when the four surviving copies of the original 1215 Magna Carta are being briefly brought together for the first time, join us to debate whether we need a US-style written First Amendment?

With a panel hailing from both sides of the Atlantic, speakers include former Attorney General Dominic Grieve, academic Sarah Churchwell, Artistic Director of the Bush Theatre Madani Younis and political analyst Peter Kellner.

Please note that the debate is invitation only, please email [email protected] if you are interested in attending.

WHERE: British Library, London

WHEN: Monday 2 February 2015, 5:30pm

This event is presented in association with the British Library

13 Nov 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Politics and Society, Russia, United Kingdom

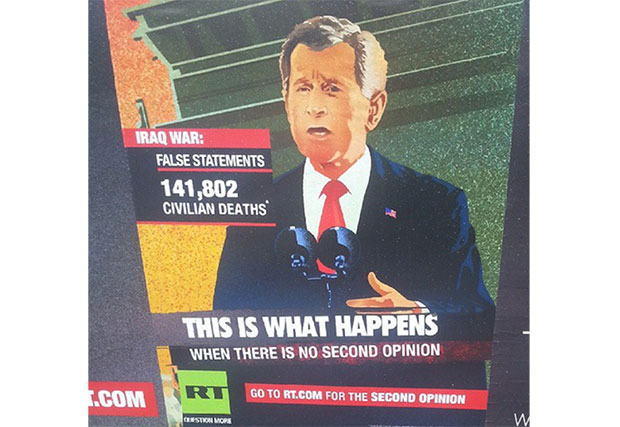

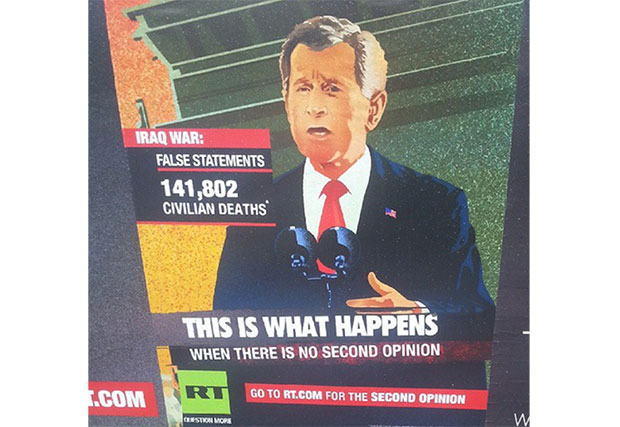

(Photo: Padraig Reidy)

There’s a poster near my house in London. It shows a poorly illustrated George W. Bush, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln early in the Iraq war, with the now infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner behind him. To his side, the tally of dead in the Iraq War (at least according to Iraq Body Count). Underneath is emblazoned the slogan: “This is what happens when there is no second opinion.” It is an advert for Russian propaganda channel RT (formerly Russia Today).

It’s a slightly muddled poster, but the signal is clear: did you feel lied to about the Iraq war? Watch RT.

Curiously, RT, which launched a UK channel on 30 October, seems to believe the poster doesn’t exist. A “report” on the RT website, dated 9 October, claims that the campaign of which this poster is part was “rejected for outdoor displays in London because of their ‘political overtones’”. The story goes on to claim that the “rejected” posters were replaced by ones that simply say “redacted”, before urging readers to download an RT app to view the ads on their phones.

But I have seen the poster. I even took a picture. Yet RT insists it has been banned, saying that outdoor advertising companies cited the Communications Act 2003, which “prohibits political advertising”. This prohibition is indeed to be found in the act, but only applies to broadcast advertisements, not billboard advertisements for broadcasters.

This is a fairly crude illustration of RT’s attitude to the truth. It is simply not an issue. What’s important is something that might sound true, something just about plausible, to suit the agenda (in this case, the agenda is threefold: one, to get people to download the app; two, to sow the belief that “they” are scared of RT; and three, to introduce the notion that political advertising is subject to a blanket ban in the UK).

Fair enough, you might say. But have you seen Fox News? Don’t all sorts of news organisations bend the truth to fit their agenda? There’s a case to be made, but there’s also a crucial difference. RT is funded and controlled by the Kremlin and is on a mission; a mission outlined in a new report by The Interpreter, part of the Institute of Modern Russia (disclosure: Index on Censorship has on occassion crossposted content from The Interpreter).

“The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money” elucidates what we had already long suspected: the Soviet Union may be dead, but Soviet tactics remain. And while the west may not want to believe it is in conflict with Russia, the Russians are already acting like it is (witness reports of heightened Russian air force activity in and near Nato airspace).

The report’s authors, Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev, describe disinformation techniques dating back to the Soviet era: straight propaganda, certainly, but also Dezinformatsiya — the planting of false stories to undermine confidence in western governments. These include alleged coup plots, the bizarre theory that AIDS was created by the CIA, even the suggestion that the assassination of Kennedy was an inside job.

The suggestion is that democracy is a sham, and that democratic governments are at best hypocrites and at worst constantly, deliberately acting against the interests of their own populations.

The best false stories always have a ring of truth and a ring of empathy. Many politicians are hypocrites, some politicians act against the interests of those they should represent. If this much is true, is it that much of a leap to imagine that the entire system is a crock? That democracy and human rights are empty terms? We’re just asking legitimate questions, as every conspiracy theorist ever has said at some point.

Conspiracy theorists find a home at RT. Presenter Abby Martin, for example, who briefly won praise for apparently criticising Russia’s actions in Ukraine, says she still has “many questions” (just asking questions!) about the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, and has used her show to expound on “false flag” attacks, alleged Israeli eugenics, and every US conspiracy theorists’ favourite, the massacre in Waco, Texas of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian cult in 1993.

All this would mean nothing if RT didn’t have a willing audience in the UK, the US and beyond. But a combination of a large budget, photogenic presenters and a certain way with a YouTube clip makes RT a serious player. It never quite veers into the straight out lunacy of Iran’s Press TV, which is quite open about its conspiracist contributors, and it looks like a serious operation. Furthermore, its positioning as an “alternative news source”, albeit one controlled by an increasingly authoritarian, paranoid and erratic Russian state, finds it fans among people who would rail against their own liberal states and societies (on the two occasions I visited the Occupy St Paul’s encampment in London, Russia Today was playing on a large screen there). All the while, the autocratic Putin is strengthened as democracy in undermined worldwide (witness how easily Putin was able to put the kibosh on effective intervention against Syria’s Assad through the relentless repetition of the line that helping the opposition would mean helping jihadist terrorists).

So what, as Lenin himself once asked, is to be done? After reports of UK broadcast regulator Ofcom’s recent investigations into RT for bias earlier this week, some people saw a chance to get RT taken off the air just weeks after it had begun. But this impulse is too close to political censorship in principle, and in practice, an ineffective sanction against a force that has huge power online, with millions upon millions of YouTube hits.

Decent democrats that they are, Weiss and Pomerantsev suggest eternal vigilance is required: we must be able to combat RT’s half truths and insinuations effectively, with hard facts and hard arguments, in order to stop them spreading. As ever, when arguments for counterspeech as the best defence against poison is suggested, one remembers Yeats’s lines: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

But this time 25 years ago, as East and West Germans embraced on top of the Berlin Wall, the world showed that the right argument can win even against the very worst. The Kremlin is playing the same games now as it did in its darkest days. Democrats should be ready to fight back.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Nov 2014 | Latvia, News, Religion and Culture, Russia, United Kingdom

Protest outside the Royal Albert Hall in London over the recent concert staged by Russian singer Valeriya (Photo: Lensi Photography/Demotix)

At first glance, there seems to be little that Latvia’s New Wave music festival and London’s iconic Royal Albert Hall would have in common.

The former is hugely popular contemporary music festival and talent spotting contest on the shores of the Baltic Sea, attracting thousands of revellers from Eastern Europe and beyond. The latter is one of the world’s most famous venues, where some of the global music industry’s biggest and best artists regularly perform. It is also home to the Proms, the premier musical event of the British establishment.

But both have recently been embroiled in the fallout from the crisis in Ukraine, as a culture war between Russia and the west threatens to widen.

Last week it was claimed by Russia’s culture minister that the New Wave festival was on the verge of being cancelled and moved to Russia after three of the headline acts were barred by the Latvian government earlier this year.

The New Wave festival in the town of Jurmala was due to see Oleg Gazmanov, Joseph Kobzon and Alla Perfilova, known as Valeriya, perform in July.

According to the Baltic Times, the trio were banned from attending by the Latvian foreign ministry over their pro Russian views on the Ukraine crises. At the time several members of the Russian State Duma called on the festival to be moved to another Russian seaside resort, and suggested Crimea as an alternative.

“Concerning the organisation of ‘New Wave’ in Crimea, we are ready to cooperate and will gladly host any creative project in Crimea,” Crimea’s Culture Minister Arina Novoselskaya was quoted as saying.

But Russia’s Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky has reopened the debate by suggesting that the festival is now on the verge of being moved permanently.

“This decision by the Latvian powers that be can be regarded with nothing except astonishment, and as a result, Jurmala stands to suffer serious economic losses,” he told the Baltic Times while at a private meeting in the capital Riga. “We are very close to making the decision to exit, because Russian artists will not tolerate such a slap in the face.”

The six day concert, which gives emerging artists around the world a chance to perform in front of large crowds, was started in 2002 and is considered one of the best in the region. Thousands attend the event and prizes for the winners can be in their tens of thousands of euros.

But big stars attend too.

Kobzon – once dubbed “Russia’s Frank Sinatra” and who is now a Russian MP – said that he was going to file a lawsuit at the European Court of Human Rights over his ban. “I’m suing the Latvian government for moral and material damages,” he told Pravda. “I had paid the hotel 11,500 euros for the time of my stay in Jurmala, but the hotel did not return the money to me.”

The Latvian foreign ministry released a statement at the time that said the three singers “through their words and actions have contributed to the undermining of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Latvian Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkevics sent a tweet that “apologists of imperialism and aggression” would be denied entry into Latvia for the festival. The tweet appears to have been deleted.

The issue has once again raised its head after a campaign was launched by anti-Putin activists to have several Russian artists banned from performing in the UK too. Both Kobzon and Valeriya, who were billed to play at a special one-off concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 21 October, were again targets of the proposed bans.

According to The Guardian, both artists signed an open letter supporting Putin’s controversial policies in Ukraine. In the week running up to the concert, Valeriya was pictured sitting next to Putin at the Russian F1 Grand Prix.

The London concert went ahead, though it would seem, not exactly as planned. Kobzon reportedly decided to not attend at the last minute, allegedly fearing he would be turned away at the UK border. Over 100 Ukrainian activists picketed the concert, holding placards that read: “Ukrainian Blood on Putin’s Hands” and “Valeria [sic] and Kobzon: Putin’s Voices of War and Death”.

“After the concert we asked some of the people who attended what was said, as they were leaving. They told us Kobzon didn’t perform, “Nadia Pylypchuk, from the London Euromaidan campaign group who organised the protest, told Index on Censorship. “Valeriya told them on stage that Kobzon couldn’t be there because of ill health. But a few days later he performed in Eastern Ukraine. He was just scared that he would not be allowed into the country,” she added.

Despite several attempts by Index to contact the Royal Albert Hall, the venue declined to answer questions about the concert, including whether Kobzon had performed.

A week later, Kobzon, who was born in the Donbass region, would be banned from entering Ukraine by the Kiev government. He nevertheless returned through the porous Russian border, which the Kiev government has little control over, to perform a concert at the Donetsk Opera House.

According to Buzzfeed he was joined on stage by rebel leader Alexander Zakharchenko for the Soviet classic I Love You, Life. Although Zakharchenko was clearly a little rusty. “It’s fine,” Kobzon reassured him after the performance. “I’m an even worse soldier than you are a singer.”

For activists back in the UK, the London concert was proof that Russia’s elite preaches one message to his home audience, whilst acting very differently abroad.

“Such hypocrisy is unacceptable,” Andrei Sidelnikov, an anti-Putin activist who has been given political asylum in the UK and who started the campaign to have the concert scrapped, told The Guardian. “In Russia, they declare that western values are bad, wrong, and not suitable for Russia. Then they travel to western countries to earn money, spend holidays, and buy real estate.”

This article was originally posted on 3 November at indexoncensorship.org

16 Oct 2014 | Draw the Line, Youth Board

This month the Index Youth Advisory Board is discussing legal regimes and how they nurture or stifle the free expression of ideas. Examples of draconian laws abound: from Russia’s law banning “homosexual propaganda” to the UK’s use of RIPA legislation to violate the confidentiality of journalists’ sources.

When it comes to free speech: laws, what are they good for?

Legal frameworks protect speech and broader free expression. Take for instance Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which tells us that we all have the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Most of us, I’m sure, would cherish this right – who wouldn’t want to be able to express themselves freely and say what they like without the interference of the state?

In the United Kingdom, Article 10 of the Human Rights Act grants citizens freedom of expression. Most countries have different forms of Article 10. It is these laws – the ones that promote and protect our right to free speech – that form the crucial pillars of any democracy.

But do all laws protect our right to free speech?

Article 10 does a good job of granting us the confidence to speak out and ensure our voices are heard, but do other laws do the same? Or are there laws that, in some way, serve to restrict free speech? The example from Russia underline the use of legislation to restrict the right to expression. The law also curtails the right to assembly, another important part of a democratic society.

When you look into Article 10 itself, you begin to learn about the restrictions of the law and begin to understand how, in many ways, the state still does have authority over our freedom of expression. For example, Article 10 can be restricted “in the interests of national security” and in order to “maintain the authority of the judiciary”.

And what about the countries that don’t have specific laws that promote freedom of expression as strongly as the UK’s Article 10? Many may find it easy to conclude that countries like Iran have more laws that serve to restrict free speech, rather than protect it. It’s interesting to look at blasphemy laws in this instance to examine whether it protects the rights of those who are religious or restricts the rights of those who wish to criticise religion.

This month on Draw the Line, we discuss the impact a country’s laws have on our freedom of expression. Join the discussion and let us know whether laws serve to protect or restrict your right to free speech.

This article was posted on 16 Oct, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org