29 Feb 2012 | Awards

Recognising innovation and original use of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate, argument or dissent

Freedom Fone by Kubatana, mobile phone technology NGO, Zimbabwe

Kubatana is an NGO based in Harare that uses a variety of new and traditional media to encourage ordinary Zimbabweans to be informed, inspired and active about civic and human rights issues. As an organisation, it continuously seeks innovative fixes to the challenges of sharing independent information in Zimbabwe’s restrictive media environment. Freedom Fone is one of Kubatana’s solutions. An open-source software, Freedom Fone helps organisations create interactive voice response (IVR) menus to enable them to share pre-recorded audio information in any language via mobile phones and landlines with their members or the general public. The software is aimed at organisations or individuals wishing to set up interactive information services for users where the free flow of information may be denied for economic, political, technological or other reasons. Freedom Fone is one of the many ways Kubatana reaches across the digital divide to inform and inspire the vast majority of Zimbabweans who do not have regular or affordable internet access.

ObscuraCam, smartphone app, USA

ObscuraCam is a free smartphone application that uses facial recognition to blur individual faces automatically. Developed by WITNESS and the Guardian Project, it enables users to protect their personal security, privacy and anonymity. In 2011 and 2012, uprisings throughout the Middle East have shown the power and danger of mobile video footage. ObscuraCam helps protect activists who fear reprisals but want to safely capture evidence of state brutality. Launched in June 2011 and based in the USA, ObscuraCam is the only facial blurring or masking application that has responded to the concerns of human rights groups, citizen activists and journalists. In addition to obscuring faces, the application removes identifying data such as GPS location data and the phone make and model.

ObscuraCam is a free smartphone application that uses facial recognition to blur individual faces automatically. Developed by WITNESS and the Guardian Project, it enables users to protect their personal security, privacy and anonymity. In 2011 and 2012, uprisings throughout the Middle East have shown the power and danger of mobile video footage. ObscuraCam helps protect activists who fear reprisals but want to safely capture evidence of state brutality. Launched in June 2011 and based in the USA, ObscuraCam is the only facial blurring or masking application that has responded to the concerns of human rights groups, citizen activists and journalists. In addition to obscuring faces, the application removes identifying data such as GPS location data and the phone make and model.

Visualizing.org, data visualisation resource, international

Visualizing.org was created to help make data visualisation more accessible to the general public. It calls itself “a community of creative people making sense of complex issues through data and design… and a shared space and free resource to help you achieve this goal”.Data analysts and graphic designers have set themselves the challenge of sharing a constantly proliferating body of public data in an accessible form. Raw data on its own might as well be censored; visualisation opens the door to open information that otherwise would be left languishing on hard disks or, if downloaded, unintelligible to the average citizen. The project offers a place to showcase work, discover remarkable visualisations and visually explore some of today’s most pressing global issues. Created by GE and Seed Media Group, Visualizing.org promotes information literacy. The portal has had a remarkable year.

Telecomix, internet activists, across Europe

Telecomix is the collective name for a decentralised group of internet activists operating in Europe. Their focus is to expose threats to freedom of speech online. During one operation, Telecomix activists published a huge package of data which proved that the Syrian government was carrying out mass surveillance of thousands of its citizens’ internet usage. Telecomix’s revelation that the technology used was supplied by US firm Blue Coat Systems has prompted serious investigations into the involvement of western technology firms in helping repressive regimes spy on their people. In mid-August 2011, Telecomix’s dispersed group of hackers came together to target Syria’s internet. Those attempting to access the internet though their normal browsers were confronted with a blank page bearing a warning: “This is a deliberate, temporary internet breakdown. Please read carefully and spread the following message. Your internet activity is monitored.” Following this, a page flashed up describing how to take precautions to encrypt usage.

Telecomix is the collective name for a decentralised group of internet activists operating in Europe. Their focus is to expose threats to freedom of speech online. During one operation, Telecomix activists published a huge package of data which proved that the Syrian government was carrying out mass surveillance of thousands of its citizens’ internet usage. Telecomix’s revelation that the technology used was supplied by US firm Blue Coat Systems has prompted serious investigations into the involvement of western technology firms in helping repressive regimes spy on their people. In mid-August 2011, Telecomix’s dispersed group of hackers came together to target Syria’s internet. Those attempting to access the internet though their normal browsers were confronted with a blank page bearing a warning: “This is a deliberate, temporary internet breakdown. Please read carefully and spread the following message. Your internet activity is monitored.” Following this, a page flashed up describing how to take precautions to encrypt usage.

supported by

29 Feb 2012 | Awards

Recognising artists, filmmakers and writers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles against repression and injustice

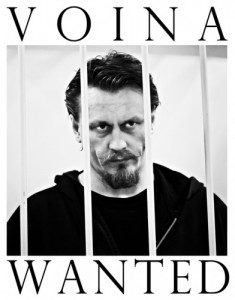

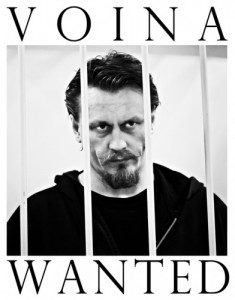

Voina, performance artists, Russia

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art.

Voina, meaning “War”, is a collective of radical Russian anarchist artists who combine political protest and performance art.

Voina’s carries out actions directed against the authorities. In June 2010, members painted a 65-metre phallus on a drawbridge in St Petersburg which, when raised, faced the city headquarters of the federal security service.

Voina members Vorotnikov and Leonid Nikolayev were imprisoned from November 2010 to February 2011 in connection with an anti-corruption protest and, in July 2011, Russian police issued an international arrest warrant for Vorotnikov. A warrant for the arrest of fellow artist Natalia Sokol was issued in December 2011.

Ai Weiwei, artist, China

AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights.

AiWeiwei is a Chinese artist and activist whose work incorporates social and political activism. He has investigated corruption and cover-ups and openly criticised the Chinese government’s record on human rights.

Ai’s 81-day detention in 2011 caused international uproar. He was arrested in April, alongside several of his friends and colleagues. Since the Chinese authorities released him on bail in June 2011, he has been fined $2.4 million in back taxes and penalties. Though officials arrested Ai for alleged economic crimes, supporters say he was punished for his activism and vocal critiques of the government. He paid a $1.3 million bond with loans from supporters, who contributed online and in person and even throwing cash over the walls of his studio in Beijing.

In November 2011, after Ai announced that authorities were investigating his cameraman for pornography in connection with photos that featured the artist and four women naked, internet users responded tweeting nude photos of themselves in support.

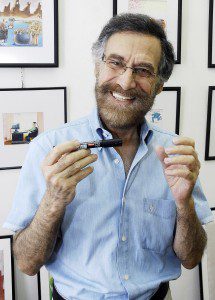

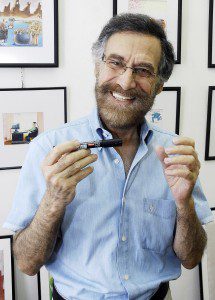

Ali Ferzat, cartoonist, Syria

Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria.

Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat has been called “an icon of freedom in the Arab world”. He has spent decades ridiculing dictators in more than 15,000 caricatures. His depictions of President Assad and the police state have helped galvanise revolt in Syria.

In August 2011, Ferzat was wrenched from his vehicle in central Damascus by pro-Assad masked gunmen who beat him badly and broke his hands. Passers-by found Ferzat dumped at the side of a road; his briefcase and the drawings inside it had been confiscated by his attackers.

Ferzat earned regional and international recognition in the 1980s with stinging cartoons of officials, autocrats and dictators including Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. Saddam Hussein called for Ferzat’s death in 1989 after an unfavourable portrait of him was exhibited in Paris and Ferzat’s cartoons have been banned in numerous Arabic countries.

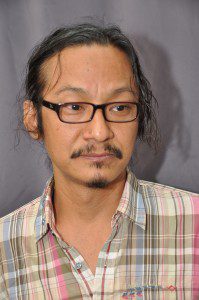

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, poet, Burma

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.

Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, a poet, filmmaker and screenwriter, co-founded Burma’s inaugural Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which took place in early January 2012.

Burmese citizens were invited to create a short film on the theme of freedom. Despite the state media’s refusal to cover the announcement, Ko Ko Gyi and his organisers received 188 submissions. Thousands gathered in Rangoon under the banner “Free Art, free thought, freedom”, to watch the selected films. More than 7,000 attendees voted for Cut This Scene to win one of five awards. The film is a satire of a government censorship committee struggling to set the criteria by which to censor films.

28 Feb 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

Former police officer and TV presenter Jacqui Hames, who was put under surveillance in 2002 by the News of the World, gave an emotional account to the Leveson Inquiry today, describing the “great anxiety” caused by the intrusion.

The former police officer, who joined Crimewatch in 1990, explained she could not think of any reason why the News of the World would put her and her then husband under investigation, but suspected that real reason for the surveillance was her police officer husband’s involvement in the investigation of the murder of private investigator Daniel Morgan. Hames suggested that the News of the World wanted to derail the case.

Hames tearfully explained how information obtained by Glenn Mulcaire could only have been gathered from her personnel file, suggesting she had been “sold down the line” by someone in the police force. Upon seeing the information in Mulcaire’s notebooks including her payroll and warrant numbers, along with previous police accommodation, Hames recalled being “shocked” and “angry”.

She began saying: “As a police officer you learn to compartmentalise, you put your private and public life into two different places.” Lord Justice Leveson encouraged her to stop as she became visibly upset, commenting “the cause of this inquiry is not to aggravate the distress caused.”

She added: “I think sometimes it’s easier to dismiss certain people because they should be able to put up with it, but I don’t believe anyone should have to put up with it and that’s why I came here today and stuck my head above the parapet.”

As a former police officer and with her presenting role on BBC TV programme Crimewatch, Hames felt she had been able to “see the media from the inside”, allowing her to undertake her current role as a media trainer for detectives. In her statement to the inquiry, she suggested enhanced media training for police officers at all levels of the force.

Hames advised the court that it was possible for police officers to have a relationship with journalists, while retaining professional integrity. She added “there’s no reason not to if you are open and honest.”

Liberal Democrat MP and phone-hacking victim Simon Hughes described an “unforgivable” failure by police to investigate the extent of phone hacking during his evidence.

Appearing before the hearing, Hughes told the court it was clear from 2006 that staff at the highest level knew the full extent of News of the World payments to Glennn Mulcaire, and described the lack of investigation from police regarding this as a “completely unacceptable failure”.

Hughes described being “frustrated even now” that action wasn’t taken in 2006. He said: “If there had been robust action in 2006 a lot of the illegal action might have been shut down and a lot of the people who are now known to be victims might not be victims or might not have suffered as much.”

During the prosecution of Glenn Mulcaire, Hughes was not told by the police the private investigator had obtained his phone number and secret office “hotline”, information the MP had tried to keep under wraps, following his involvement as a witness in a murder case.

In 2011, during a meeting with officers from Operation Weeting, Hughes said he was shown pages from Glenn Mulcaire’s notebooks, along with other evidence, including transcripts of telephone calls, his home address and phone numbers. In the notebooks, there were three names of News of the World employees.

“The police showed me the pages [from Mulcaire’s notebooks], they asked me to identify what I could. They indicated there may be in this book some names of other people with whom Mr Mulcaire was working … They opened the issue without leading me to the answer.”

Hughes also explained that during the 2006 Liberal Democrat leadership campaign, his office was contacted by a journalist from The Sun regarding a “private matter”. In a meeting with the journalist, Hughes was advised that the newspaper had acquired records of telephone calls made by the MP, relating to his sexuality. Following an interview with the tabloid, The Sun ran the article “outing” Hughes.

Previous to the media speculation around his sexuality, Hughes described being “odds on favourite” to win the leadership vote, and described a “direct impact between that revelation, press coverage and my political reputation.”

Hughes described complaining to his mobile phone provider of “a systemic failure” with regards to his voicemail, after messages he knew had been left were unavailable, and after occasions when his voicemails were completely inaccessible.

The MP also discussed the “unhealthy relationship” between the press and politicians: “I understood how influential tabloids became, saw the desperate effort of party leaders to gain favour with media. I regarded it increasingly unhealthy.”

Hughes added that he believed scrutiny of politicians in the media is important: “Of course we have to engage with the media, and we should be subject to their scrutiny. I’m not asking for a less robust press and less active engagement, but there shouldn’t be people going in through the back door of Downing Street. We need to have a system which is transparent, and open and we know the score.”

Guardian journalist Nick Davies returned to the hearing to give a lively testimony for the second module of the inquiry.

Davies explained that often official police sources prefer quotes to remain unattributed, his definition of “off the record”. He said: “90 per cent of the work I do is off the record. Certainly that includes officially authorised interviews with police officers. It really isn’t sinister. I think the immediate fear that a police officer has when they sit down with a journalist is that they will be misquoted. Off the record eliminates that.”

The journalist described the risks of closing down all communication between journalists and police, comparing it to saying “I got food poisoning last night, I am never going to eat again,” but stressed the importance of “getting to the bottom of what went wrong with official flow of information” relating to phone hacking, describing it as “catastrophic.”

He added: “it isn’t that official sources are inherently good or that unofficial sources are inherently bad. Don’t identify unidentified sources as the cause of the problem. It would be a mistake to say off the record is the source of the problem, it’s not sinister, it helps people to tell the truth.”

Branding the self regulation and media law in this country as “useless”, Davies suggested taking the Freedom of Information act as a theoretical model: “all info should be disclosed unless it is covered by the following exemptions. I’d like to see the same model for the police. Why not be open? It helps avoid abuse.”

Davies added that it was not an ethical worry for a police commissioner to meet with newspaper editors to talk about policy, or specific cases, but that it became an issue if “we now discover it was an active ingredient in the subsequent failure to investigate News of the World.”

Chris Jefferies also appeared before the hearing for a second time. Jefferies, who was wrongly arrested on suspicion of murdering his tenant Joanna Yeates in 2010, described a pique in media interest following his second statement to the police in December of that year.

He said: “until then I had not been the subject of any particular media attention but that suddenly changed. A Sky news team were extremely anxious to talk to me, a large number of reporters and photographer’s appeared at the address where I lived. They had somehow got to hear about that second statement, and they were extremely anxious to hear if I believed I had seen Jo Yeates leaving the property on the 17th December with one or other people.”

He added: “There was feverish interest in talking to me and fact it happened day before arrest was remarkable to me.”

In a very measured response, Jefferies added that reports that police had said he was “their man”, was “not be beyond the bounds of possibility that the police might want to give the impression of considerable confidence, that a considerable step forward had been taken in the investigation.”

Jefferies suggested that it should be a “far more serious offence” for police who disclose inappropriate information to the press.

In his witness statement, Jefferies said: “It is my very firm view that it must be considered a far more serious offence than it currently is for police to disclose inappropriate information to members of the press and that to do so should be an imprisonable offence, subject to a public interest defence.”

28 Feb 2012 | Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa

Over 70 per cent of East Africa’s population lives in rural communities: despite the proliferation of radio stations, weekly and daily newspapers, and television stations, in Tanzania alone there are 17 radio stations, 61 national papers and 11 state and private TV stations. In Kenya and Uganda there are even more media outlets but despite this, and even though ‘freedom of information’ is being enshrined in constitutions (in Kenya and Tanzania), there are major challenges to free speech and accessing information.

Mwalimu Asya Mgongo is one of three teachers on the island of Chole Mjini, total population 950 people. Like many East Africans lucky enough to have a job, her monthly 120,000 TZ shillings (£45) teacher’s salary supports eight family members. She is listening to her phone as she sits on ‘the harbour’: a small slab of concrete overlooking the Indian Ocean, her headscarf covering her head — this is a 100 per cent Muslim island. “For me getting the information to teach my children really is a problem — Dar Es Salaam is over 12 hours away by boat, local bus and another bus. Books! You’re joking! They’re gold here. The government gives us text books, but there’s no postal system, and the even the newspapers arrive a day late, if they arrive, so there’s little point. I do have a radio, I listen to the BBC World Service and the German one, and I try and tell as many people as possible”. She looks out to sea a bit dreamily: “Internet, being able to get BBC news daily on the internet, I would love that.”

Her sentiments are echoed by Mama Dayema and Mama Mahogo, both cooks at the local Chole Mjini eco-lodge on the island, which, over the 20 years of its existence, has single-handedly raised the levels of education on the island by building a primary school and funding up to eleven people to go to university — a first for the island. Mama Dayema is clear about what information is missing from their lives: “We tend to rely on taxi drivers (on the sister Mafia island, a ten minute boat ride away) for information on staples like maize, rice, cooking oil. We’d really like to be able to chat to the guests in English. I am the only villager on the island with solar power, which I found out about through information from foreigners. The key is education, completely: my children need to get ahead and know how the world is, even if I don’t. We are cut off, ignored actually, by mainland government, and policies, but in some ways I don’t mind. We have abundant fruits — oranges, mangoes, and real trust here, we look after each other. On the mainland (Tanzania) there’s thieves, diseases, adulterers, bad people.”

Salma Meremeta left Mafia, for work in the capital; “Honestly we are isolated and abandoned here, the government doesn’t care about us one bit — when I come home I am shocked by the lack of information here, it’s bad.”

Certainly for tourists the island is as close to paradise as it gets, and the isolation a “feature” of the attraction. However, it’s a recognised problem that rural people, particularly women, are marginalised from the creation, circulation and consumption of information. Ironically rural people are often far more critical, and vociferous about political policy issues (water and the price of basics) because they are living so close to the breadline. Yet media houses and reporters are based in capitals like Kampala and Nairobi, and infrastructure — lack of good roads and the expense of flying — makes distribution of newspapers extremely expensive (thus impossible). It is rare for reporters to get the resources, support and incentives to report on “rural” issues.

On Chole Mjini island (which is 250km south of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, 1.5 square km wide, in the middle of the Indian ocean) the main public space in the village is dominated by a television hooked up to one of the two electricity points on the island. Football results and news are the popular crowd-pleasers. Up to two hundred men at a time pay 200 TZ shillings (ten pence) to watch for the evening; for 100 TZ shillings they can also charge their phones. As Saidi, says “It’s not really ok for women to be in public watching television. But we are an oral culture, so for example things like health messages (recently the US government donated mosquito nets to the island) don’t get spread on tv on radio, but by word of mouth. Or by the Imam at the call to prayer. We’re extremely forgiving and compassionate here, as a Muslim culture, so our sick people, we have two HIV victims, they are looked after by us, they are not ostracised. If we feel our sheha’s (Chiefs) are being unreasonable or unfair, we ignore them, or get rid of them. The island is so small there’s a sort of democracy. Go to the mainland? Me! No, never, I love it here”.

Figures for east African internet useage are not entirely accurate, but according to survey group Afrobarometer Tanzania scores the lowest, with just one per cent of the population having access to internet, . On Chole Mjini no-one has a computer, thus there is no internet access. Mama Dayema’s daughter, Mwana, is a striking, educated 24 year old with her mobile phone neatly wrapped in a flannel and tucked into her bra. She is ambivalent “Yes, I suppose part of me is interested in the fact that slavery was only abolished here in 1922, or the Shirazi Persians built palaces here in the past, but honestly I am more interested in modern things, like music and fashion from Dar Es Salaam, or football results, not history.”

One of the downsides of lack of information is the prevalence of gossip. People pick up snippets of news, but it gets mangled through the rumour mill. It’s telling that despite the lack of media in Swahili there is no concrete way to say “I am bored”.

ObscuraCam is a free smartphone application that uses facial recognition to blur individual faces automatically. Developed by WITNESS and the Guardian Project, it enables users to protect their personal security, privacy and anonymity. In 2011 and 2012, uprisings throughout the Middle East have shown the power and danger of mobile video footage. ObscuraCam helps protect activists who fear reprisals but want to safely capture evidence of state brutality. Launched in June 2011 and based in the USA, ObscuraCam is the only facial blurring or masking application that has responded to the concerns of human rights groups, citizen activists and journalists. In addition to obscuring faces, the application removes identifying data such as GPS location data and the phone make and model.

ObscuraCam is a free smartphone application that uses facial recognition to blur individual faces automatically. Developed by WITNESS and the Guardian Project, it enables users to protect their personal security, privacy and anonymity. In 2011 and 2012, uprisings throughout the Middle East have shown the power and danger of mobile video footage. ObscuraCam helps protect activists who fear reprisals but want to safely capture evidence of state brutality. Launched in June 2011 and based in the USA, ObscuraCam is the only facial blurring or masking application that has responded to the concerns of human rights groups, citizen activists and journalists. In addition to obscuring faces, the application removes identifying data such as GPS location data and the phone make and model. Telecomix is the collective name for a decentralised group of internet activists operating in Europe. Their focus is to expose threats to freedom of speech online. During one operation, Telecomix activists published a huge package of data which proved that the Syrian government was carrying out mass surveillance of thousands of its citizens’ internet usage. Telecomix’s revelation that the technology used was supplied by US firm Blue Coat Systems has prompted serious investigations into the involvement of western technology firms in helping repressive regimes spy on their people. In mid-August 2011, Telecomix’s dispersed group of hackers came together to target Syria’s internet. Those attempting to access the internet though their normal browsers were confronted with a blank page bearing a warning: “This is a deliberate, temporary internet breakdown. Please read carefully and spread the following message. Your internet activity is monitored.” Following this, a page flashed up describing how to take precautions to encrypt usage.

Telecomix is the collective name for a decentralised group of internet activists operating in Europe. Their focus is to expose threats to freedom of speech online. During one operation, Telecomix activists published a huge package of data which proved that the Syrian government was carrying out mass surveillance of thousands of its citizens’ internet usage. Telecomix’s revelation that the technology used was supplied by US firm Blue Coat Systems has prompted serious investigations into the involvement of western technology firms in helping repressive regimes spy on their people. In mid-August 2011, Telecomix’s dispersed group of hackers came together to target Syria’s internet. Those attempting to access the internet though their normal browsers were confronted with a blank page bearing a warning: “This is a deliberate, temporary internet breakdown. Please read carefully and spread the following message. Your internet activity is monitored.” Following this, a page flashed up describing how to take precautions to encrypt usage.