20 Nov 2012 | News

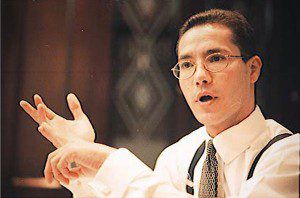

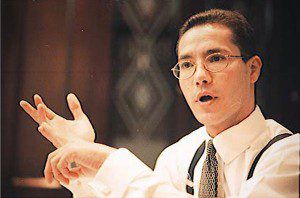

LONDON (INDEX). Exposing financial crime is a dangerous career path. David Marchant — an investigative journalist and publisher of OffshoreAlert — knows that. He has been sued numerous times and has never lost, his first accuser is currently serving 17 years in prison for tax evasion and money laundering.

Offshore alerts specialises in reporting about offshore financial centres (known as OFCs), with an emphasis on fraud investigations, and also holds an annual conference on OFCs focusing on financial products and services, tax, money laundering, fraud, asset recovery and investigations. It caters to financial services providers and other financial institutions.

Marchant talks to INDEX — ahead of the OffshoreAlert Conference Europe: Investigations & Intelligence, 26 – 27 November — about the importance of free expression and the peculiarities of his trade.

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?

DAVID MARCHANT: It is unfair to blame the global economic crisis on offshore financial centres. It is, essentially, a people-problem, the majority of whom live in the world’s major countries.

For me, the most interesting aspect of the crisis is that it confirmed what I already knew, i.e. many of the world’s major banks and financial services firms are not well managed. A significant part of the problem is that offering huge short-term financial incentives invites your personnel to act in a manner that is not in the long-term interests of a company. It encourages risk-taking and the concealment of losses to create the appearance of success, as opposed to actual success. It seems that few, if any, material changes have been made to the system, that you can’t change human nature overnight and that history is destined to repeat itself in the future. Other than the crisis causing more schemes to collapse early and there being more to write about, it has had no effect on OffshoreAlert’s investigative reporting.

INDEX: Greek investigative journalist Kostas Vaxevanis was arrested a few days ago in Athens for publishing the “Lagarde List” —containing the names of more than 2,000 people who hold accounts with HSBC in Switzerland (one imagines, hoping to escape the taxman). The list remained unused for two years after Christine Lagarde passed it onto then Finance Minister Giorgos Papakonstantinou. What do you think about it?

DM: It would not surprise me if the Greek authorities had indeed sat on this information. Governments and corruption or incompetence go hand in hand.

INDEX: Tax evasion is not considered money laundering in some jurisdictions, and it looks less frightening than laundering drug or criminal proceeds. Do you hold any views on this subject?

DM: Money laundering is a criminal offence in its own right. The predicate crimes vary country by country and, in some countries, tax evasion is not among them or was not among them now at one time. In the Cayman Islands, for example, fiscal offences were initially omitted from the jurisdiction’s money laundering laws but the jurisdiction was forced — screaming and kicking — into adding them at a later date. Tax evasion clearly should be a predicate crime. Paying taxes is a price we must pay to live in a civilised society. Who wants to live in an uncivilised society? Certainly not me.

INDEX: How do you balance the need for privacy with the need for transparency in the offshore world?

DM: As a journalist, the more transparency the better but information must be handled responsibly. The word “privacy” is a soft word for secrecy and people have secrets for a reason, i.e. they are typically trying to conceal something that is illegal, immoral or otherwise shameful.

INDEX: You receive sponsorship from security companies like Kroll Advisory Solutions. The global intelligence industry caters for crooks and corrupt, repressive governments alongside corporate clients. Twenty years ago, the value of this sector was negligible — today it is estimated to be worth around $3bn. Any thoughts on this?

DM: To be clear, OffshoreAlert is an independent organisation, not beholden to anyone or anything other than accuracy and fairness. We have limited advertising on our web-site but we do have sponsors for our financial due diligence conferences, which is a commercial necessity. The global intelligence industry is like any other. Companies aren’t particularly choosy about who they will accept as clients. It’s all about making money. I have no idea whether the global intelligence industry has become more prevalent or not over the last 20 years. If it has grown significantly, however, I would guess that much of such growth would be fuelled by banks and other financial firms having to comply with tougher anti-money laundering laws.

INDEX: How do you compare your work with that of, for example, Wikileaks?

DM: I have little or no respect for WikiLeaks. In my limited dealings with the organisation, I have found Wikileaks to be amateurish and fundamentally dishonest. In its very early days, it was clear to me that, in one action at federal court in the United States, Wikileaks clearly misled the court. It is not trustworthy. I consider Julian Assange to be an irresponsible, hypocritical, over-hyped poseur. His major talent seems to be self-publicity. I cringe when I see him described as a journalist. It denigrates the entire profession. Fortunately, there are few, if any, similarities between Wikileaks and OffshoreAlert. We’re not in the same business or market and there is a gulf of difference in the level of professionalism between the two.

INDEX: You actually own 100 per cent of OffshoreAlert and I understand that you are not insured against libel and other legal risks in order to avoid “lawyering” your exposes. Is this correct? Is it necessary in order to safeguard your journalistic independence?

Former accountant and self-styled “offshore asset protection guru”,Marc Harris was convicted of money laundering and tax evasion by the US in 2004

DM: I do indeed beneficially own OffshoreAlert in its entirety. Prior to launch in 1997, I looked into purchasing libel insurance. The premiums were reasonable but the problem was that every article would need to be pre-approved by a recognised libel attorney. That would have been costly and would have inevitably led to the attorney recommending that stories be watered down, which would have defeated the primary purpose of OffshoreAlert, which is to expose serious financial crime while it is in progress. I have an even better de facto insurance policy: If someone sues me for libel, I will take all of my incriminating evidence to law enforcement, and do everything in my power to ensure that the plaintiff is held criminally accountable for their actions. This is no idle promise. The first person to sue me for libel (self-proclaimed “King of the Offshore World” Marc Harris) thought he could put me out of business. Instead, he is currently serving 17 years in prison for fraud and money laundering.

INDEX: However, you have been taken to court for libel on many occasions and always won. So the objective behind these law suits seems to be to intimidate or drain you dry. How do you about surviving suing threats?

DM: OffshoreAlert has been sued for libel multiple times in different countries and jurisdictions. [He was sued in the USA (state and federal court), Cayman Islands, Canada (Toronto), Grenada (by then Prime Minister Keith Mitchell), and Panama]. We’ve never lost a libel action, never published a correction or apology to any plaintiffs and never paid — or been required to pay — them one cent in costs or damages. It is a record of which I am very proud. I know how the game is played, I am extremely resourceful, and I am not intimidated easily. This might come across as conceited, but my attitude towards plaintiffs is that I am brighter, tougher and more talented than you and your attorneys and that, if you want to sue me, I will do everything in my power to ensure that you pay the ultimate price of being criminally prosecuted for your actions.

INDEX: According to organisations such as ours, English libel law has been shown to have a chilling effect on free speech around the world. Especially worrying is “libel tourism”, where foreign claimants have brought libel actions to the English courts against defendants who are neither British nor resident in this country. What do you think about it?

DM: British libel law, generally, is among the most repulsive pieces of legislation that exists in the civilised world. It is a reprobate’s best friend and protects the reputations of people who don’t deserve to have their reputations protected. I couldn’t operate OffshoreAlert in the UK or in any country or jurisdiction that has adopted similar laws because OffshoreAlert would be sued out of existence. British libel law is considered to be so repugnant that, in 2010, the United States passed The SPEECH Act that renders British libel judgments unenforceable in the US there is no de facto free speech in Britain because of its libel laws. I find the entire British legal system to be terrible in dispensing justice. In that regard, it is light years behind the legal system that exists in the US, where OffshoreAlert is based.

Miren Gutierrez is Editorial Director of Index

19 Nov 2012 | Asia and Pacific

President Barack Obama’s speech at Yangoon University appears to be another step in what he described as a “remarkable journey” for the country. The progress does look real.

Back in 2007, BBC special correspondent Fergal Keane wrote a report for Index after he returned from reporting the brutal crackdown on the Saffron revolution.

He alluded to the necessarily secretive nature of entering the country and meeting interviewees:

I won’t go into how I managed to get into the country: suffice to say that I was able to operate for several days without being picked up. It was nerve wracking and posed immense human and journalistic challenges.

While describing the immense difficulties local activists faced, he was optimistic about the role of the web in opening up the country and helping local democrats get their story out. “[T]he “bamboo curtain” has been lowered once again,” wrote Keane. “But not for long I believe.”

Yangon, Burma: A child holds a picture of Aung San Suu Kyi along with President Obama (Demotix)

Five years on, and Burma seemed to have changed almost beyond recognition for Keane:

“Since the beginning of 2012 I’ve visited Burma three times. Each trip has been on an official journalist visa. Not once have I been harassed, intimidated or interfered with. I have reported from city slums and rural villages, from huge opposition rallies and from within sedate government compounds. On my first ‘official’ trip I walked the streets of downtown Rangoon interviewing people at random. Again my expectation was that a secret policeman would appear from the shadows and bundle myself and the camera team away. But nothing happened.”

Shortly before Keane wrote that dispatch, the Burmese government had announced that it was scaling down censorship. On 1 June Tint Swe, head of the Press Scrutinisation and Registration Department was quoted by AFP saying:”There will be no press scrutiny job from the end of June. There will be no monitoring of local journals and magazines.”

Remarkable in a country where newspapers and magazines had faced pre-publication censorship for decades.

After the release of political prisoners in 2011, including opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi and and satirist Zarganar, the first real test of whether the broader population would enjoy extended free speech under the newly liberalised regime came in January of this year, with the Arts of Freedom Film Festival, which more or less passed the test (barring the rejection of some submissions from outside Burma.

Since then, progress has been pretty much consistent. But there is a long way to go yet. Burma is nowhere near a democracy, and the disturbing reports of violence against the Rohinga Muslim population (and the opposition NLD’s apparent indifference to it) are certainly cause for alarm.

Obama spoke today Burma’s need to embrace Roosevelt’s four fundamental freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Burma has huge challenges in all these areas.

Padraig Reidy is news editor at Index

19 Nov 2012 | India

A war over free expression between Indian citizens and their government is raging, with social media serving as the battlefield.

Two girls were arrested in Mumbai today, one for having updated her Facebook status asking why the city was observing a bandh — a city-wide shut down — to commemorate the death of an influential regional leader, Bal Thackeray. The other simply ‘liked’ the comment. The update was brought to the notice of Shiv Sena local leader, outraged at the insult to his party’s founder he went to the police and had them arrested. The pair were released on bail today, but not before one of the girl’s uncle’s orthopaedic clinic was ransacked by an angry Shiv Sena mob.

Shaheen Dhadha, 21, had written:

People like Thackeray are born and die daily and one should not observe a bandh for that

The incident comes only a month after India’s first Twitter arrest. In October 2012, Ravi Srinivasan, a small-town businessman was arrested for tweeting to his 16 followers that that Karti Chidambaram, a politician belonging to India’s ruling Congress party and son of Finance Minister P Chidambaram, had “amassed more wealth than Vadra” [Sonia Gandhi’s wealthy son-in-law].

Ravi Srinivasan was arrested for this tweet

Srinivasan was arrested for suggesting one cabinet minister’s son is more corrupt than the son-in-law of another senior politician.

The seemingly politically motivated arrest has just added fuel to the fire to a heated debate about how defamation and hate speech on social media should be dealt with. It also raises the question — is the government more interested in protecting itself than its citizens?

At a forum, The Power of Social Media for Governance organised in March 2011, while praising social media and e-government/commerce initiatives, Information minister Kapil Sibal suggested that social media users also discuss the dangers of this new platform:

All kinds of opinions are put forward and that is dangerous. Freedom of speech has some caveats. How do you ensure that (social media) sites incorporate constrains [SIC] of freedom of speech?

The comment seemed to be aimed at social media users using these new mediums to criticise the many corruption scandals in Indian public life. The Indian public were furious at their political leaders. Sibal’s predecessor, A Raja, was a perfect example. He was forced to resign after becoming embroiled in a huge telecom scam.

Although there had been a story the previous month about a riot that apparently broke out due to a Facebook page that denigrated the architect of the Indian constitution, Dr BR Ambedkar, social media had not really been used for positive political action in India.

In October 2010, however, an anti-corruption movement led by activist Anna Hazare slowly began to caputure the imagination of the nation. As Hazare, compared by the Indian press to Mahatma Gandhi, protested corruption, the media and the public rallied behind him. The movement, now known as India Against Corruption [IAC] used Facebook and Twitter to connect with urban Indians — the middle class — who had borne the brunt of corruption for years. IAC racked up followers and fans by the thousands, and in April 2012, Hazare went on an indefinite hunger strike to force the government to draft a stronger anti-corruption bill. It was all India social media users could talk about. The web was key to Anna’s success. Today, the IAC Facebook page has over 754,000 supporters.

2011 was marked by a face-off between the government and “civil society” that may mark a turning point in India politics. The sleeping giant, the middle class, woke up and logged on.

Toward the end of 2011 it was revealed that Sibal suggested pre-screening of social media content to ensure that “objectionable content” was removed before it could offend.

According to leaked reports, Sibal pointed to a Facebook page that maligned Congress party president Sonia Gandhi and said “this is unacceptable”. At the time, experts like Pranesh Prakash from the Center for Internet and Society pointed out that the existing IT Act (amended in 2008) allows people who send information “that is grossly offensive and of a menacing character” to be sentenced to three years in prison. Prakash argued that the amount of content was too vast for social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter and Youtube to pre-moderate and would delay their immediacy. More importantly, why should a third party be forced to judge what is objectionable or not, if there were already laws in place?

This idea of pre-screening content has been revised. But the theme has been coming up again and again as the government seems to be unsure of what strategy it should employ to stop both really offensive material, but also, it seems, any criticism of itself from social media networks.

In February, Facebook agreed to comply with local laws and “remove content, block pages or even disable accounts of those users who upload contents that incite violence or perpetuate hate speech.” This, Sibal insisted, was not censorship but he still raised the spectre of new laws designed to curtail social media in India. It wasn’t long before #KapilSibalisanidiot started trending on Twitter. Later that month it was revealed in a Google’s Transparency Report that the government of India had asked the search giant to remove 358 items in the first half of 2011. Only eight of these items were classified as hate speech; the vast majority were criticisms of the government (including videos on Youtube and posts on the social network Orkut.)

In August 2012, India found itself in an unprecedented situation caused by text messaging and social media. Rumours of an attack against Assamese migrants by Muslims were being sent across the country via SMS. Many Assamese, over 400,000 by some estimates, in different parts of the country started heading home, fearing their lives. The government put in place a restriction to only five-SMSes per day to control the rumour mill. Soon after, the minister gave more interviews about social media, suggesting that incidents like the Assamese exodus were the reason he wanted the help of intermediaries in helping curtail the influence of anti-national elements and protecting the sensitivities of individuals and communities. However, as Twitter agreed to comply with the government in blocking any communally charged tweets, the Twitter accounts of some journalists also got blocked, forcing the minister to clarify that the government was not seeking to block individual accounts. The damage was done, as most observers felt that the government had tried to silence its critics on social media instead pursuing any larger objective.

Which brings us back to the first Tweet (as well as Facebook update) induced arrest. Srinivasan was booked under Section 66A of the IT Act (amended 2008). This can jail, for up to three years, anyone convicted of disseminating material that is “grossly offensive”, has “menacing character” or is false with the aim of causing “annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult,” among other related cyber crimes. The women arrested for the Thackeray Facebook post were arrested under the same Act (and also Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code that relates to religious sentiments, event though they were discussing a political, not religious, figure).

Section 66A — the very piece of law that internet experts flagged as an alternative when Sibal suggested pre-screening social media content, is now being abused. The current controversy is layered. The first point of contention is that the arrest would never have been made so swiftly if the “victim” had not been the son of a powerful minister. The second is that Section 66A (IT Act, 2000) is unclear, which means, say experts, its open to abuse, as can be seen by current events.

In India, the distrust of the political class has never been sharper, with extreme reactions from the establishment. In 2012 itself, a cartoonist was arrested under Section 66A (IT Act, 2000) for mocking the chief minister of Bengal, while elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh, another cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested under Section 124 of the Indian Penal Code for mocking India’s corrupt politicians. How the government balances Indian citizens’ right to free expression against the need curtail genuine incitement will be a test of its democratic credentials.

Mahima Kaul is a journalist based in New Delhi. She focuses on questions of digital freedom

19 Nov 2012 | South Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa

The South African Communist Party (SACP) this week made a public call for a law to be instituted to protect the country’s president against “insults”. The call, by one of its provincial branches, was in response to growing public outrage about R240 million (about £17m) worth of taxpayer’s money spent on upgrading the private homestead of the incumbent, Jacob Zuma.

Minister for higher education and SACP general secretary Dr Blade Nzimande reportedly supported the call by the KwaZulu Natal SACP but later said he is calling for a public debate on the issue.

Two investigations are underway into the price tag attached to “security upgrades” at Zuma’s private residence in Nkandla in rural KwaZulu Natal, which far exceeds that of residences of former presidents.

South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma speaking to a union congress (Demotix)

In parliament last week (15 Nov) Zuma insisted that “all the buildings and every room we use in that residence was [sic] built by ourselves.” In response, Lindiwe Mazibuko, the leader of the official opposition Democratic Alliance (DA), pointed out that the upgrades are not limited to “security” but include 31 new buildings, lifts to an underground bunker, air conditioning systems, a visitors’ centre, gymnasium and guest rooms. It reportedly even includes “his and hers bathrooms”.

Since the excessive amount became known at a parliamentary meeting in May this year, investigative journalists have requested further information using the Protection of Access to Information Act. The public works department, however, refused to comply, citing the National Key Points Act, which makes it illegal to distribute information about sites related to national security. The public works ministry also launched an investigation to find the whistleblower who leaked the information to the media, with a view to prosecution.

The SACP believes that questions about the Nkandla extensions, including by DA leader Helen Zille who led a thwarted visit to the homestead, harm Zuma’s dignity. In a thinly veiled threat, the SACP claimed such questions would undermine South Africa’s “carefully constructed and negotiated reconciliation process and could unfortunately plunge our country into an abyss of racial divisions and tensions.”

Insult laws “protecting” presidents from criticism exist in France, Spain and across South America and Africa.

Christi van der Westhuizen is Index on Censorship’s new South African correspondent

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?

INDEX: As investors continue to pour millions of pounds each month into offshore bank accounts, the Western world is in economic disarray, demanding much more from law-abiding taxpayers to bailout banks. What is your view on the economic crisis, and has it had any effect on the type of investigative journalism you practice?