20 Sep 2013 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

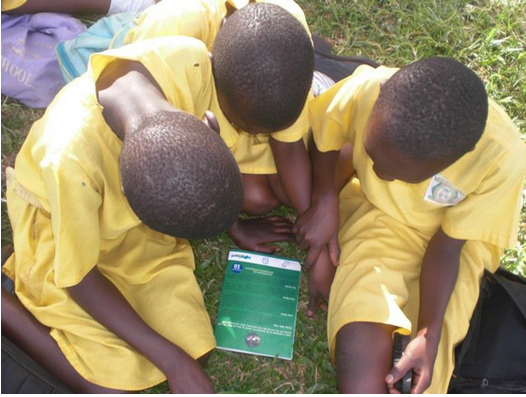

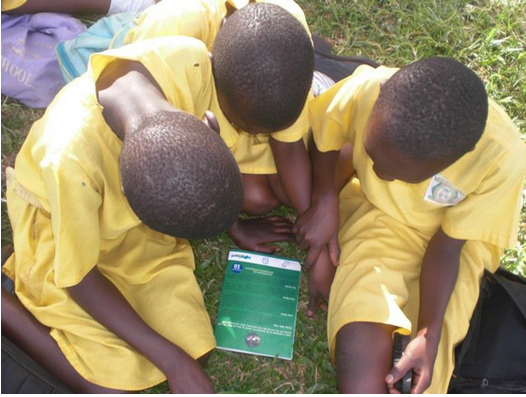

It could be a true story. In Uganda there are an estimated 2.75 million children engaged in work, although not many of those will have the happy ending. But The Little Maid is a work of fiction, written by Oscar Ranzo, a Ugandan social worker turned author who has penned five children’s books. Now, The Little Maid is being distributed to schools across the country low-cost (5,000 Ugandan shillings or $1.90 each) through his Oasis Book Project. The project aims to improve the reading and writing culture in Uganda and provide school-children with entertaining but educational stories to which they can relate. Ranzo sells most of his books to schools, with the proceeds used to publish more titles. However, he also donates copies to more impoverished areas.

In 1969, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa’s best-known poets and fiction writers, declared Uganda a ‘literary desert’. “What we want to do with this project is create an oasis in the desert,” explains Ranzo. “That’s why I called it the Oasis Book Project.”

The small print

Excluding textbooks, there are only about 20 books published in Uganda annually. According to a study last year by Uwezo, an initiative aimed at improving competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged six to sixteen years in East Africa, more than two out of every three pupils who had finished two years of primary school failed to pass basic tests in English, Swahili or numeracy. For children in the lower school years, Uganda recorded the worst results.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, Ranzo was privileged to have a grandfather who had a library and attended a private school that held an after class reading session. He was a particularly avid fan of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

“But Mum was a nurse and she wanted me to be a doctor. I wanted to pursue literature and she told me ‘no you can’t do that’, so I did sciences,” says Ranzo, stressing that literature, which remains optional in secondary school, is not taken seriously in Uganda.

Furthermore, many local publishers do not see writing fiction as profitable. “They’d rather publish textbooks and get the government to buy them,” Ranzo explains.

His books are available in two central Kampala bookshops for 8,000 shillings ($3). But in the past 15 months fewer than 20 have moved from the shelves, while he has sold over 3,000 to 20 schools in three districts.

Fiction imitating life

Saving Little Viola, his first book in which the female protagonist, Viola, was introduced, was published in 2011 by NGO Lively Minds. The story ends with Viola being saved by her best friend from two men who want to use her for a ritual sacrifice. UNICEF funded its distribution to 36 primary schools across Uganda as part of a child sacrifice awareness programme.

The primary aim of the Oasis Book Project is to encourage reading, although Ranzo admits he would like people to discuss his stories, which have themes close to his heart. Children being forced into work, the theme of The Little Maid, is something he has witnessed himself.

“Many kids are brought from villages to work as maids in homes in towns or cities, and the treatment they are subjected to is terrible in many cases,” says Ranzo.

His next book, The White Herdsman, which will be released in 2014, deals with the impact of oil production on communities, a timely subject for Ugandans with oil production expected to start in 2016. The book tells the story of a village where water in the well has turned black after an oil spill. A witchdoctor blames the disaster on an albino child.

Ranzo’s stories have been welcomed at Hormisdallen Primary, a private school in Kamwokya, Kampala. English teacher Agnes Kasibante, speaking to Think Africa Press, praises the book’s impact. “It’s actually a big problem in Uganda, most children don’t know how to read. At least those books give them morale to continue loving reading,” she says.

Ranzo has also penned Cross Pollination, a collection of fictional stories for adults about the spread of HIV in a community. According to a recent report, Uganda may not meet its target to increase adult literacy by 50% by 2015.

“I’ve worked in a big multinational company where people have jobs but they can’t write. Reading can help develop this,” says Ranzo, who is currently attending the University of Iowa’s 47th annual International Writing Program (IWP) Fall Residency.

Uganda’s literary comeback

Jennifer Makumbi, 46, a Ugandan doctoral student at Lancaster University, is one of a new generation of Ugandan authors. She won the Kwani Manuscript Project, a new literary prize for unpublished fiction by Africans, for her novel The Kintu Saga. She said Taban Lo Liyong’s description of Uganda as a literary desert was “heartbreaking, especially as in the 1960s Uganda seemed to be poised to be a leading literary producer”.

“But perhaps it is exactly this description that is pushing Ugandans to write in the last ten years,” she continues. “Yes, we have not caught up with West Africa yet but… there are quite a few wins.” In recent years, two female Ugandan authors, Monica Arac de Nyeko and Doreen Baingana, won the Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize respectively. Makumbi’s Kwani prize adds her to a list of eminent Ugandan authors.

Makumbi is optimistic about the future of Ugandan literature: “These I believe are indications that Uganda is on its way.”

This article was originally published on 17 Sept 2013 at Think Africa Press and is reposted here by permission.

20 Sep 2013 | News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Freedom of expression is protected by the German Constitution and basic laws. There is room for improvement, with Germany’s hate speech and libel laws being particularly severe.

Germany’s biggest limits on freedom of expression are due to its strict hate speech legislation which criminalises incitement to violence or hatred. Germany has particularly strict laws on the promotion or glorification of Nazism, or Holocaust denial with paragraph 130(3) of the German Criminal Code stipulating that those who ‘publicly or in an assembly approve, deny, or trivialise’ the Holocaust are liable to up to five years in prison or a fine. Hate speech also extends to insulting segments of the population or a national, racial or religious group, or one characterised by its ethnic customs.

Germany still has strict provisions in the criminal code providing penalties for defamation of the President, insulting the Federal Republic, its states, the flag, and the national anthem. However, in 2000, the Federal Constitutional Court stated that even harsh political criticism, however unjust, does not constitute insulting the Republic.

Freedom of religious expression is compromised through anti-blasphemy laws criminalising ‘offences related to religion and ideology’. Paragraph 166 of the Criminal Code prohibits defamation against ‘a church or other religious or ideological association within Germany, or their institutions or customs’. While very few people (just 10) have been convicted under the blasphemy legislation since 1969, the impact of hate speech legislation is seen more frequently, in particular in the prosecution of religious offences. In 2006, a pensioner in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia was given a 1-year suspended sentence for printing ‘The Koran, the Holy Koran’ on toilet paper, and sending it to 22 Mosques and Muslim community centres. In 2011, nine of the 18 operators of the far right online radio programme ‘Resistance Radio’ were given between 21 months and three years in prison for inciting hatred.

Germany has also seen heated debate over a widespread ban on religious symbols in public workplaces, especially affecting Muslim women who wear headscarves.

Half of Germany’s 16 states have, to various extents, banned teachers and civil servants from wearing religious symbols at work. Yet this is not applied equally to all religions; five states have made exceptions for Christian religious symbols.

Media freedom

Government and political interference in the media sector continues to raise concerns for media independence, with several incidents of interventions by politicians attempting to influence editorial policy. In 2009, chief editor of public service broadcaster ZDF, Nikolaus Brender saw his contract terminated by a board featuring several politicians from the ruling Christian Democratic Union. Reporters Without Borders labelled it a ‘blatant violation of the principle of independence of public broadcasters.’ In 2011, the editor of Bild, the country’s biggest newspaper, received a voicemail message from President Christian Wulff, who threatened ‘war’ on the tabloid which reported on unusual personal loan he received.

Media plurality is strong among regional newspapers though due to financial pressure, media plurality declined in 2009 and 2010. Germany has one of the most concentrated TV markets in Europe, with 82% of total TV advertising spend shared among just two main TV stations in Germany. This gives a significant amount of influence to just 2 broadcasters and the majority of Germans still receive their daily news from the television.

The legal framework for the media is generally positive with accessible public interest defences for journalists in the law of privacy and defamation. However, Germany still has criminal provisions in its defamation law, which although unused, remain in the penal code. Germany’s civil defamation law is medium to low cost in comparison with other European jurisdictions, places the burden of proof on the claimant (a protection to freedom of expression) and contains a responsible journalism defence, although not a broader public interest defence.

Digital

The digital sphere in Germany has remained relatively free with judicial oversight over content takedown, protections for online privacy and a high level of internet penetration (83% of Germans are online). Germany’s Federal Court of Justice has ruled that access to the internet is a basic right in modern society. Section 184b of the German Penal Code ‘states that it is a criminal offense to disseminate, publicly display, present or otherwise make accessible any pornographic material showing sexual activities performed by, on or in the presence of a child.’ Germany has also ratified and put into the law the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cyber Crimes from 2001. Mobile operators also signed up to a Code of Conduct in 2005, which includes a commitment to a dual system of identification and authentication to protect children from harmful content. This was reaffirmed and made binding in 2007.

There are concerns over the increased use of surveillance of online communications, especially since a new antiterrorism law took effect in 2009.

In 2011, German authorities acquired the license for a type of spyware called FinSpy, produced by the British Gamma Group. This spyware can bypass anti-virus software and can extract data from the device it is targeting. Two reports by the German Parliamentary Control Panel, from 2009 and 2010, stated that several German intelligence units had monitored emails with the amount of surveillance increasing from 7 million pieces items in 2009 to 37 million in 2010. However, Germany’s Constitutional Court ruled in February that intelligence agencies are only allowed to collect data secretly from suspects’ computers if there is evidence that human lives or state property are in danger and the authorities must get a court order before they secretly upload spyware to a suspect’s computer.

Germany’s tough hate speech legislation also chills free speech online. In January 2012, Twitter adopted a new global policy allowing the company to delete tweets if countries request it, meaning that tweets become subject to Germany’s hate speech laws. The latest Twitter transparency report states that German government agencies asked for just 2 items to be removed. In October 2012, Twitter also blocked the account of a far-right group, Better Hannover, after a police investigation.

Artistic freedom

Artists can work relatively freely in Germany. Freedom of expression in arts is protected under the Constitution, and is largely respected, especially for satire or comedy. Yet, the freedom of expression of artists is chilled through strict hate speech and blasphemy laws.

The German authorities very rarely use blasphemy laws against artists. However, there have been several examples of art being subjected to censorship due to religious offence. In 2012, at the exhibition ‘Caricatura VI – The Comic Art – analog, digital, international’ in Kassel, a cartoon created by cartoonist Mario Lars was removed after protests that it offended religious sensibilities.

There is persistent sensitivity around artistic works depicting the Nazi period. In April 2013, the German version of an Icelandic author’s book was ‘censored’ by its publisher, who cut 30 chapters from Hallgrímur Helga’s novel, ‘The woman at 1000°’. Key passages about Hitler, concentration camps and SS were censored to fit the German market.

19 Sep 2013 | Belarus

This week, all 25 members of Belarus Free Theatre were in London ready to start their rehearsal for King Lear at the Globe, back after its triumph at the Globe to Globe Festival last year. The company is split between those living precariously in exile in London, and the rest who continue to work illegally and underground under appalling, oppressive conditions back in Minsk and getting everyone together is fraught with difficulties and danger.

This week, all 25 members of Belarus Free Theatre were in London ready to start their rehearsal for King Lear at the Globe, back after its triumph at the Globe to Globe Festival last year. The company is split between those living precariously in exile in London, and the rest who continue to work illegally and underground under appalling, oppressive conditions back in Minsk and getting everyone together is fraught with difficulties and danger.

Seeing them all together at a fundraising event in central London, they looked like a group of young actors anywhere in the world. But in order to get here, 20 of them had to be smuggled out of the country, taking different routes across the multiple borders of the land-locked country to fly from Vilnius, Riga, Warsaw, Kiev or Moscow to London. And the whole trip seemed in jeopardy when on Saturday night, their underground performance in Minsk was raided by the police. This is the first time that the performances have been raided since early July. The police usually just take down everyone’s details as they leave the show. But the significance of this raid was that they stopped the show mid-performance, taking down the actor’s audiences names and passport numbers before letting them go home.

They have been working out of the same small house, teaching students, rehearsing performing for their shows for several years now. But after this raid the actors feel it will not be long before they are unable to use the building. Finding a new building is extremely difficult because it means finding someone brave enough to rent their space to an illegal theatre company.

19 Sep 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, News and features

Tributes to murdered activist Pavlos Fyssas (pic: Christos Syllas-Dellis)

Thousands of protesters gathered on Wednesday evening in Athens near the place where Pavlos Fyssas, a 34 year-old antifascist hip hop artist was murdered by a Golden Dawn supporter.

“The blood is running, it seeks revenge”, they shouted, a slogan echoing the December 2008 riots , when 15 year-old student Alexandros Grigoropoulos was killed by two policemen.

The 45 year-old man who carried out the stabbing has told police that he was a supporter of far-right party Golden Dawn. This was clearly a politically motivated killing, added to a sequence of intimidation events and attacks carried out by Golden Dawn against immigrants and asylum seekers.

On 17 January, Shehzad Luqman, an immigrant worker from Pakistan was lethally stabbed by two men. Police later found pre-election pamphlets of Golden Dawn in the house of one perpetrator.

In December 2012, Amnesty International reported on this issue. In addition, Human Rights Watch has found that there is evidence connecting the attackers on immigrants with members of or affiliated with far-right groups such as Golden Dawn.

No matter how useful these findings may be, they were clearly not at the “agenda” of the rally at Keratsini. Young and old antifascists, together with immigrants, have been increasingly struggling with Golden Dawn vigilantes in the past five years. The murder of Fyssas comes as no surprise. A lot of people somehow anticipated the tragic event.

“The regime, in co-operation with Golden Dawn is clearly escalating the confrontation with political dissidents. This is why we’re here today. And we have to step up the intensity of this political struggle. Everywhere,” said a demonstrator, local resident of Keratsini.

Some 3,000 – 4,000 members of an organised anarchist block was heading towards Golden Dawns’ offices in Nikaia, while at the same time, demonstrators attacked Keratsini’s police station. Almost instantly clashes began: Riot police squads tried to disperse groups of demonstrators with the typical use of excessive force.

In an alley, the head of a police squad was heard shouting “Come on, let’s go and fuck them up”. Middle-aged people from the neighborhood curesed them, while young antifascists threw Molotov cocktails and stones.

Keratsini district, a working class neighborhood, was established after Greek refugees fled Asia Minor on 1922. The greater area of Piraeus (Nikaia, Perama, Keratsin), known for its anti-Nazi struggle, was historically affiliated with the political left.

This picture though seems to be fading away. According to polling company “Public Issue”, Golden Dawn has doubled its electoral influence on these areas. Moreover, it has worked its way on socially penetrating existing political views.

On June 2012, Egyptian fishermen were attacked in Perama after an inflammatory and racist speech by Golden Dawn MP Yannis Lagos, who said that the party would hold them accountable for their actions. A few days ago, again in Perama, members of the Communist Party (KKE) were brutally attacked by Golden Dawn’s supporters while putting up posters for an upcoming festival.

Last nights’ clashes have led to a total of 130 detentions and 34 arrests while tweeters were reporting a demonstrator had been heavily injured by a direct teargas shot. Questions about the way police responded at the place of the assassination remain unanswered. Witnesses on TV broadcasts this morning said that police were reluctant to involve at the fight before the stabbing.

There were protests against the murder throughout the country. Latest reports suggest that there have been discussions on emergency legislation to ban Golden Dawn’s acts.

This article was originally published on 19 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

This week, all 25 members of Belarus Free Theatre were in London ready to start their rehearsal for King Lear at the Globe, back after its triumph at the Globe to Globe Festival last year. The company is split between those living precariously in exile in London, and the rest who continue to work illegally and underground under appalling, oppressive conditions back in Minsk and getting everyone together is fraught with difficulties and danger.

This week, all 25 members of Belarus Free Theatre were in London ready to start their rehearsal for King Lear at the Globe, back after its triumph at the Globe to Globe Festival last year. The company is split between those living precariously in exile in London, and the rest who continue to work illegally and underground under appalling, oppressive conditions back in Minsk and getting everyone together is fraught with difficulties and danger.