26 Nov 2013 | Africa, Digital Freedom

Amid concerns that the proposed African Union Convention on Cybersecurity (AUCC) will limit free speech online the drafters of the AUC have agreed to receive input from outside organisations.

The Web We Want, a campaign aimed at promoting an internet where everyone can participate in the free flow of knowledge, ideas, collaboration and creativity, put forward a proposal after criticism that the convention should not be passed until changes have been made to it.

The convention, which will be signed in January 2014, proposes the prevention of cybercrime in 15 African states “through the organisation of electronic transactions, protection of personal data, promotion of cyber security, e-governance and combating cybercrime”. According to the Norton Cybercrime Report 2012, South Africa ranks 3rd globally for the number of cybercrime victims, behind Russia and China.

However it has been suggested that the convention should not be passed in its current form as it “dangerously imposes broad limitations on freedom of expression by permitting the interception of content data and traffic data on unfounded grounds, such as ‘where the imperatives of the information so dictate’”.

According to the Kenyan-based Strathmore University’s Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology (CIPIT) the convention could abuse Africans’ right to privacy, harm freedom of expression and place too much power in the hands of judges who, in the “public interest”, will have the authority to intercept individuals’ electronic communications without their permission.

Taking this into account this week will see an online discussion on the proposed changes to the AUCC by Kenyan and Ugandan stakeholders. Sponsored by KICTAnet, the Kenya ICT Action Network, and in partnership with Web We Want the five day digital event will call for a discussion of articles from the convention in need of further clarification and recommendations. The Web We Want has called upon international NGOs to put forward their concerns regarding the AUCC and internet freedom to be deliberated over the coming week.

This article was posted on 26 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Nov 2013 | Bangladesh, News, Politics and Society

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

On 15 January, Asif Mohiuddin left his office in Uttara, an upmarket area of Bangladesh’s capital city, Dhaka. He was accosted by three unidentified men. They stabbed him several times in the neck and back. He was admitted to hospital in a critical condition.

Mohiuddin, who identifies as an atheist and writes a widely read and award-winning Bengali-language blog, survived the attack. But that was not the end of his troubles. In April, still struggling with persistent ill-health after the knife attack, he was arrested for posting “offensive comments about Islam and Mohammed”. Now awaiting trial after several delays, he faces a possible 14 year jail sentence and a fine of 100,000 Euros on the charge of “hurting religious belief”.

The month after Mohiuddin was attacked, another blogger, Ahmed Rajib Haider, was hacked to death outside his house in Dhaka. A frequent critic of religious fundamentalism in Bangaldesh, Haider’s death – like the attack on Mohiuddin – is widely thought to be the work of Islamic extremists.

Yet, as the subsequent arrest of Mohiuddin and three other bloggers in April demonstrates, journalists in Bangladesh face a double threat: Violent retaliation from Islamist groups on the one hand, and official repression on the other.

Bangladesh has the largest number of media outlets among the world’s least developed countries. It has 50 national daily newspapers, of which eight are English language, 25 television channels and more than 300 regional magazines. Its widely watched TV talk shows are host to robust political debate. But despite these impressive statistics, the last year has seen a significant deterioration in press freedom. According to monitoring groups, 2013 alone has seen more than 100 attacks on members of the press.

This worsening climate for journalists should be seen in the context of a polarised political situation. Antagonism between the ruling party, the Awami League, and the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party, is nothing new. But political tension has now spread outside this narrowly partisan rivalry, to a broader disagreement about the kind of country Bangladesh should be. In April this year, the Shahbagh demonstrations saw tens of thousands of secularists taking to the streets. Counter-protests by Islamists drew similar numbers. Mohiuddin, Haider, and other bloggers were all advocates of the Shahbagh protests.

Much of this polarisation is related to a war crimes tribunal set up by the Awami League, which is prosecuting individuals for crimes dating back to the 1971 war of independence, when Bangladesh separated from Pakistan. Many of those standing trial are members of the Jamaat-e-Islami, an Islamist party allied with the opposition. In February, a senior Islamist was sentenced to life in prison. This kick-started the Shahbagh protests: secularists felt the sentence was too lenient, advocating the death penalty, while Islamists and their supporters say that the tribunals are merely being used to stamp out the opposition. Against this backdrop, journalists and bloggers who are critical of one side or another are vulnerable to retaliation from vigilantes or officials.

Perhaps the most high profile case is that of Mahmadur Rahman, the editor of Amar Desh, a major pro-opposition newspaper, who criticised the tribunals. He was arrested in April on charges including sedition and remains in prison. Two Islamic TV channels which broadcast images of violence by security forces against Islamist protesters have been taken off the air. In March, the government intervened to stop TV channels broadcasting a speech by an opposition leader.

There has also been a spate of attacks against journalists who simply attend street protests to cover them. In April, Nadia Sharmeen, a journalist for Ekushey TV, was chased down the street and beaten by Islamists while covering a large protest.

While much of this violence against journalists is being carried out by non-state actors, arrests of journalists and bloggers have created a climate of fear.

“We’ve definitely seen panic within the blogger community in Bangladesh,” says Sumit Galhotra, Asia researcher for the Committee to Protect Journalists. “During the arrests of bloggers earlier this year, Islamists published a list of 84 bloggers they deemed blasphemous. According to local accounts, this list was shared with the government, and led to anxiety for many bloggers who expressed criticism of politicians or Islamist groups. Some bloggers went underground or stopped writing altogether for fear of being attacked or arrested.”

International reporters are also feeling the effects of the clampdown on press freedom. The world spotlight turned to Bangladesh in May, after a garment factory collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is acutely image conscious, and international journalists faced problems obtaining visas to cover the crisis. CNN anchor Christine Amanpour raised this in a televised interview with Hasina. “We never stop any media to come to Bangladesh,” was her response. “Every country has rules and regulations.”

While these tight restrictions on foreign reporters gaining access to Bangladesh means that important developments in the country are underreported worldwide, it is, of course, local journalists who bear the brunt. The last year has seen a drastic worsening in press freedom. But as elections approach and the political situation looks set to become, if anything, more antagonistic and polarised, there seems to be little chance there will be any imminent improvement for freedom of speech.

This article was posted on 26 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

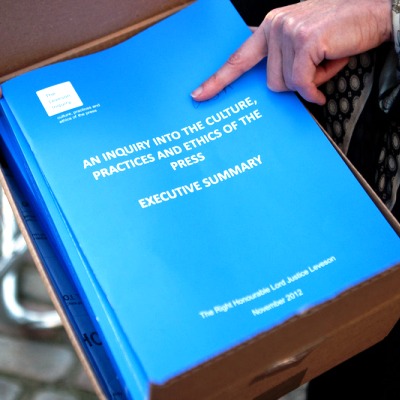

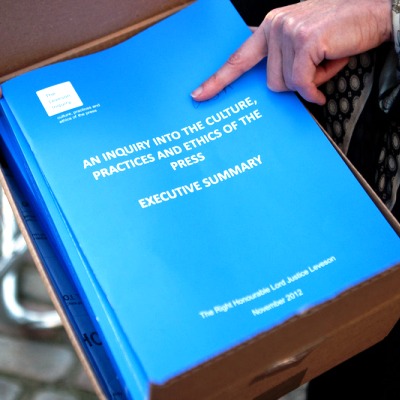

26 Nov 2013 | Comment, Media Freedom, News, United Kingdom

Martin Moore of the Media Standards Trust has written a long article for the New Statesman on the “topsy-turvy” world of the debate on press regulation and restrictions.

Moore undoubtedly makes some good points about the absurdity of some newspapers protesting potential political interference in the press while not raising a even the mildest objection to the government and secret services actual threats to the Guardian over its coverage of GCHQ surveillance techniques (similar points were made with elan by the Spectator’s Nick Cohen a few weeks ago).

The MST director berates newspapers for having “got the debate the wrong way round” both “in principle and in practice”.

But Moore and his comrades who support the Royal Charter, in the Media Standards Trust, Hacked Off, and individuals, themselves must take some blame for the topsy-turviness of the language around regulation.

Take the idea of “exemplary damages”, which, it is proposed, publications that do not sign up to a recognised regulator will be subjected to.

The pro-Royal Charter argument has been that the existence of exemplary damages, and the avoidance of them are “incentives” to join the regulator. They are not. They are a punishment for not joining the regulator. An incentive would suggest putting publications at an advantage; but under the current proposals, all that joining a regulator does is to put publications on a level footing with individuals or organisations who would not be considered subject to the regulatory scheme. An “incentive” to avoid default punishment is akin to a threat from a protection racket.

Further on in his article, Moore calls for a British version of the US’s First Amendment. It’s a nice idea.

But Moore says that Lord Justice Leveson proposed a British First Amendment. This is not the case.

What Leveson recommended was this:

In passing legislation to identify the legitimate requirements to be met by an independent regulator organised by the press, and to provide for a process of recognition and review of whether those requirements are and continue to be met, the law should also place an explicit duty on the Government to uphold and protect the freedom of the press.”

At first glance, that’s all very lovely. But it is meaningless at best, dangerous at worst, and certainly not a First Amendment style law.

Meaningless because all sorts of countries have constitutional guarantees of a free press. China, for example, states in article 35 of its constitution that “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration.” Fine words.

Dangerous as it could imply that the government of the day ultimately holds press freedom in its hands. This, it may be argued, is the case anyway, but to explicitly say it is not ideal. As noted in a recent Huffington Post article by Hacked Off’s Brian Cathcart, the British government has made many attempts in the past to stifle press freedom. I don’t really see why we should explicitly say the concept belongs to them.

The first amendment states simply:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

To claim that Leveson’s proposal, specifically to create a law about freedom of the press, is the same thing, is odd. When coupled with the proposal of punitive measures for those publishers who do not wish to play the government’s game, the claim is absurd.

This article was originally posted on 26 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorhip.org

26 Nov 2013 | News, Politics and Society, Uganda

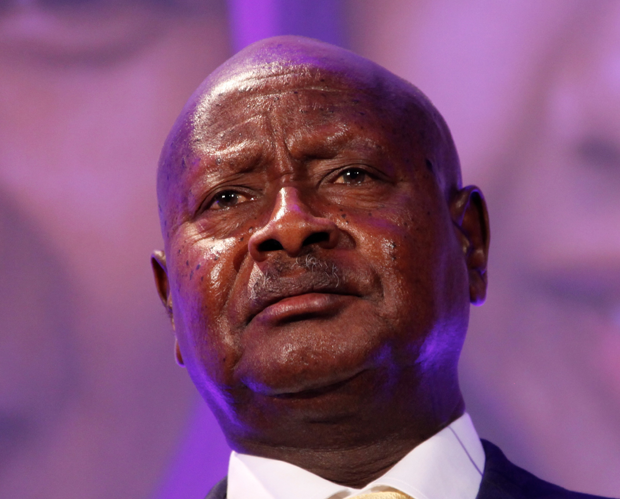

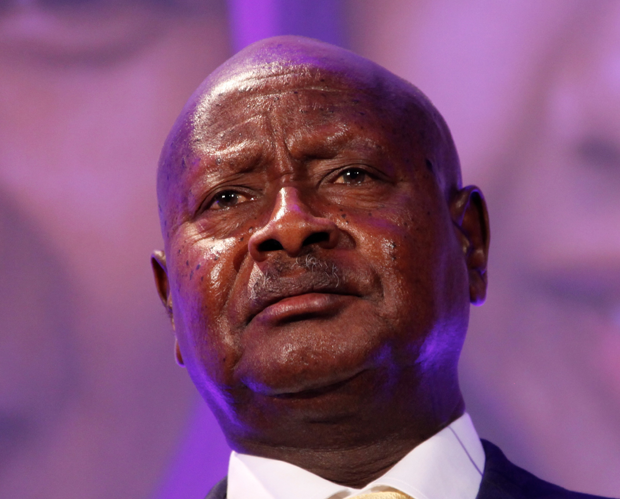

The government of longtime Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni has been accused of intimidating journalists covering the impeachment of the lord mayor of Kampala, who is a member of an opposition political party. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Against the backdrop of the political uproar following the attempted sacking of Kampala’s lord mayor, journalists reporting the story have been summoned to give statements to the police. Observers say that the government is gagging the media by barring comments from politicians who don’t toe the official line.

Media covering the case have also been attacked. On 25 November, journalist Allan Sewanyana, who is also a councillor on the Kampala City Authority, was beaten by police as he attempted to deliver a petition calling for a court injunction against the impeachment proceedings. Journalists from different media houses were sprayed with tear gas and stopped from reporting on the chaos that erupted downtown after news of the lord mayor’s removal filtered out.

Eight months ago, the government of President Yoweri Museveni started a process of ousting the mayor of Kampala, Lord Mayor Erias Lukwago, a member of the opposition Democratic Party (DP). This process led to the establishment of a tribunal, by many labelled a “kangaroo court,” where Lukwago had to defend himself against the accusation of neglect of duty levelled at him by pro-government city councillors. The tribunal found him guilty. Battle lines have been drawn: The government has moved to impeach the mayor and the opposition parties have thrown their weight behind the mayor by calling for nationwide protests.

The explosive situation has drawn coverage from the country’s media and entangled journalists. So far, two reporters covering the events have been summoned to the police to make statements. Meddie Nsereko, who works with radio station CBS FM and television station NBS TV was summoned over comments he made on his radio talk show “Kiriza oba Gaana” (“Believe it or not”). He was given stern warnings against inviting opposition politicians to speak on his show. This comes at a time when CBS FM is picking up the pieces of its 2009 closure. Back then, the government shut the broadcaster over coverage of riots that erupted after authorities stopped the Buganda King from touring parts of the country. It was out of business for over a year. With this experience still fresh in mind, CBS FM has bowed to pressure and stopped inviting opposition politicians to speak on that show.

The second journalist, Basajja Mivule of Akaboozi ku Bbiri FM, was summoned by the security chief of Kampala, also for inviting opposition politicians to his show. He was severely reprimanded. Akaboozi ku Bbiri FM is owned by Uganda’s finance minister, Maria Kiwanuka. Now Mivule has to make a choice between his professionalism or losing his job.

The government has threatened NBS TV because it recorded the “ugly scenes” that happened at the city hall and streamed them on social media. According to some sources, the “Black Mamba” — a shadowy security outfit — is said to have attacked the journalists outside the city hall and court. This same group is said to be associated with the kidnapping of presidential hopeful Kizza Besigye in 2005.

Pictures have been published of journalists and civil society members being rounded up and beaten by the police and other security groups that are not easily identified. Even ardent supporters of the system feel that things are falling apart.

Despite the official intimidation, the Ugandan public are aware of the situation. The spirit of defiance can be felt in all parts of Kampala, even with the heavy police deployment.

“What should we do? They will not allow us all to go city hall to follow the deliberations on how they are impeaching the lord mayor we elected. They never consulted us as voters, and now they are chasing all journalists away from the deliberations. Who will keep us informed on what is going on? So they want us, the voters, to remain in the dark on what is happening, and expect us to stay calm? That is impossible,” one resident of Kampala said.

Although the government has come out to deny that it is targeting journalists and that the incidents which have happened so far are isolated, no one seems to believe this. The biggest challenge for journalists however, is the lack of a well-organised body that can take the government to task when these excesses happen.

Ugandan journalists have so far failed to unify themselves. The government knows this very well, and it is taking advantage of that weakness.

This article was published on 26 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org