31 Oct 2013 | Belarus, News, Religion and Culture

Members of the Belarus Free Theatre in fall 2012

Keeping tight control over every sphere of social life is the general policy of the Belarusian authorities. This is true not only about politics, economy or media; arts and culture face censorship as well.

Music: to “black lists” and back

Rock music has always had social protest at its core. Belarusian state ideologists still keep this idea in mind. Lyrics written in the Belarusian language and popularity among opposition supporters are two features that can ensure a rock band gets in trouble.

The authorities of Belarus are not really inventive and sophisticated in the ways to silence the musicians they consider “harmful”. Unofficial “black lists” of rock bands and singers were introduced; they have not been openly public, but managers of radio stations or concert organisers and promoters are aware of them. No tracks of a “forbidden group” are broadcasted by FM-stations; no club organises a gig of a blacklisted artist, even if they know it will definitely be sold out.

During a press conference in January 2013 President Alexander Lukashenko publically asked the Head of his administration to provide him with this “black list” – suggesting there is not one.

“Believe me, I have never made any orders or requests to create any ‘black lists’ to restrict anyone from singing or dancing here. If someone pays such artists for them to heap dirt upon our country, I wish they sing to those who order such music. But I don’t know about any of these facts,” the country’s ruler told a journalist who asked the question.

“His will to get rid of ‘black lists’ might be genuine. We all got to the point when everybody wants to get rid of these black lists: musicians, audience, officials, even the president himself. But it is not easy to do, because the system is in place, and it is the system of fear that works autonomously; it is installed in the society so strongly that even Lukashenko himself barely controls it,” says Aleh Khamenka, a frontman of a famous Belarusian folk-rock band “Palac”.

He admits the situation changed a bit after the press conference in January. For instance, “Palac” was previously black-listed and had to perform under different names (e.g. “Khamenka and friends”) to be allowed on stage in Belarus; now they can openly organise concerts as “Palac” again.

But the “thaw” for rock musicians in Belarus has not been long. A new Presidential Decree, signed in June 2013, suggested an organiser of any concert must receive a special permission in a local Department of Ideology.

“De-facto, in many regions of the country such permissions were to be obtained even before the decree was signed. Now this method of censorship became law,” says Vital Supranovich, a musical producer.

Cinema “spoilt by censorship”

Production of most films in Belarus is funded by the state. But the question is whether anyone sees them.

“Quite a lot of movies are produced, but have you seen any of them? I doubt it. These movies are dull and not interesting for the audience, they are spoilt by existence of censorship. And state ideologists attempt to censor even films they do not fund, by putting pressure on production companies and trying to influence the content,” says Yury Khashchavatski, a Belarusian director, well-known for his documentaries about President Lukashenko and repressions against political opposition in Belarus.

Direct censorship is ensured by “professional propagandists”, who are appointed to manage cultural institutions. For instance, Uladzimir Zamiatalin, who used to be a chief ideologist of the Presidential Administration, was the CEO of Belarusfilm, the state cinema company of Belarus, for quite a long time.

“If you want to make a movie here, film something with a title like ‘Belarus is a country of true democracy’; thus you will be sure you are allowed to produce it without much interference,” says Khashchavatski.

Censorship goes far beyond production. Belarus has a special list of movies that are banned from distribution in the country. It used to be public, and was posted on the official website of the Ministry of Culture, but was deleted from there afterwards – “not to advertise those movies.” At the time it was public, the list included, for instance, Antichrist by Lars von Trier (that won a prize of the Cannes Film Festival) or movies by Tinto Brass.

Theatre: Online performances vs. censorship

Belarus Free Theatre is another example of how artistic freedom is restricted by the authorities of the country. Police officers are people who never miss its performances in Belarus: not because they are ardent theatre goers, but because they stop actors from performing.

“Every time the Free Theatre stages a play in Belarus, there come the police that stop the play. But this is just a visible part of restrictions; real repressions take place outside the stage. All our actors are fired from state theatres, expelled from universities; almost all of them were detained or arrested. We feel this pressure all the time,” says Nikolay Khalezin, the art director of Belarus Free Theatre.

He believes, the theatre is dangerous for the authorities, because it is independent and pays no attention to state censorship and demands from official propagandists. The price the BFT pays for this artistic freedom is harsh: the audience of their plays in Belarus is very limited; they can only stage small performances in tiny semi-clandestine premises they can find. Two of their new plays, Trash Cuisine and King Lear, that gathered huge audiences abroad, are impossible to stage in Belarus – not only because no theatre allows them in, but also because two of the actors were deported from the country in 2008 and are not allowed in.

“We have found new opportunities to present our work to Belarusian public. During Edinburgh Festival we organised live online broadcast of Trash Cuisine; it was on 22 August and it was Sunday, thus many Belarusians were able to watch our play from home,” says Nikolay Khalezin.

The idea worked. The first broadcast received 6,000 views, 85% of which were from Belarus. State censors in Belarus could do nothing about it.

According to Yury Khashchavatski, art helps to inform and educate people; it promotes real human values, rights and freedom – and this is exactly what irritates the authorities. They prefer ignorant citizens that are easier to rule, and they use censorship to prevent people from thinking and questioning the reality presented by official propaganda.

“Why are the authorities so afraid of independent artists? The answer is quite simple: Art is dangerous for the authoritarian regime, because it turns obedient population into real citizens,” says Khashchavatski.

This article was originally published on 31 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Oct 2013 | News, Russia

A Russian court pulled the license of Rosbalt Information Agency after warnings over the use of “obscene” videos in its reports.

Roskomnadzor, the Federal Service for Oversight of Communications and Information Technologies, filed an action against Rosbalt after it issued two warnings to the agency. The reason for the warnings were articles by Rosbalt that contained two YouTube videos, including a music video by Pussy Riot, a well-known Russian punk band. According to officials, the videos contained obscene words and expressions.

Russian law suggests a mass media outlet can be closed down for “numerous warnings for violations”; usage of obscene words has been such a violation in Russia since a relevant law was adopted in April 2013.

“We have several grounds to appeal against this decision to the Supreme Court,” says Rosbalt’s lawyer Dmitry Firsov, who called today’s decision “unprecedented.”

For instance, the decision to withdraw the agency’s license was made despite the fact Rosbalt had appealed against both warnings, and there have been no court rulings on any of the cases yet. Besides, the YouTube videos were removed by the agency from their articles immediately after the warnings.

Nikolay Ulyanov, the editor-in-chief of Rosbalt, was previously fined 20,000 roubles (around £400) for the presence of obscene words in the YouTube videos. Rosbalt is going to appeal against that fine as well.

31 Oct 2013 | News, United Kingdom

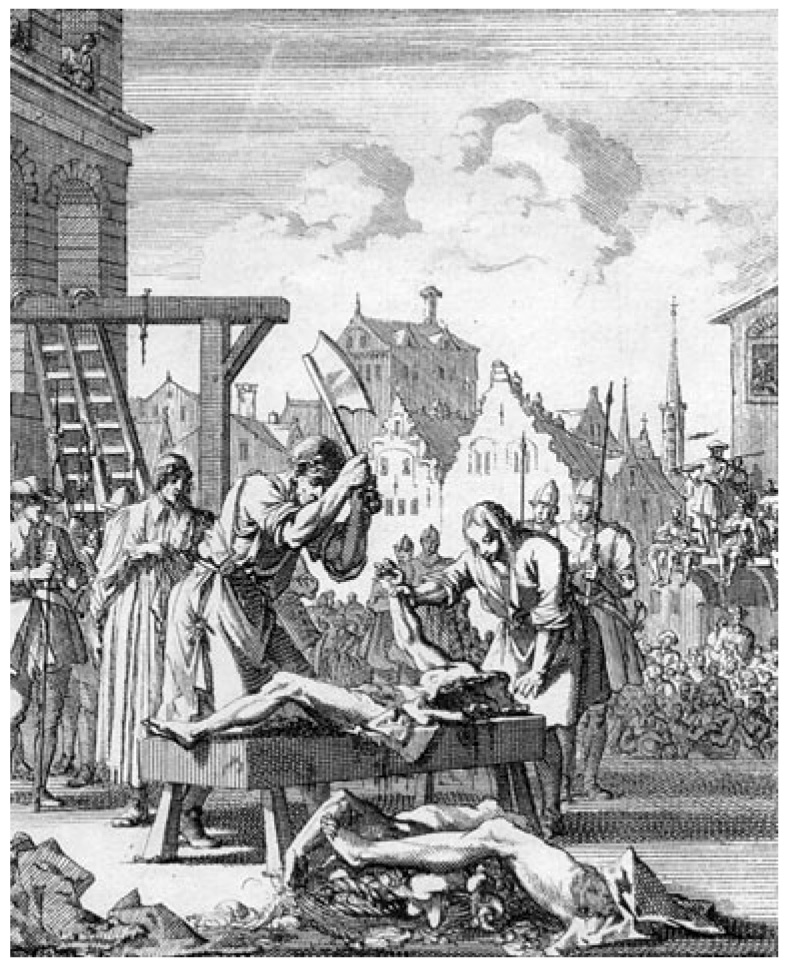

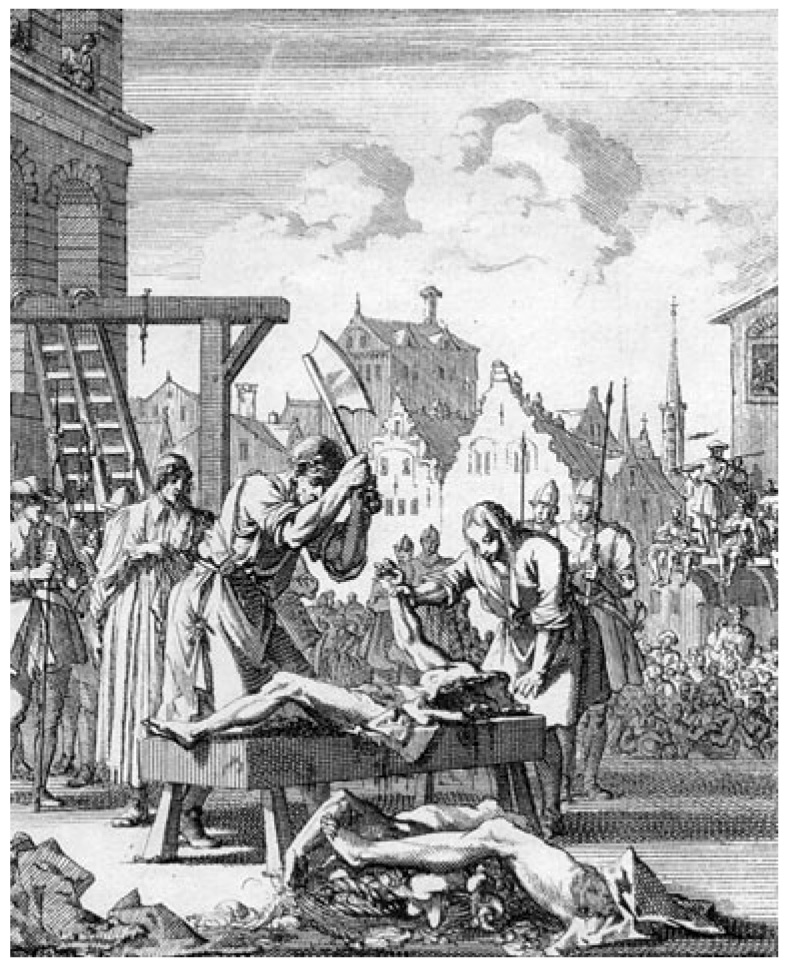

As the royal charter on press regulation was approved by Queen Elizabeth II, Index on Censorship takes a look at crime and punishment the last time the state controlled the press.

The Licensing Order 1643 censored the press by introducing pre-publication licensing, registration of all printing materials with the names of author, printer and publisher, the seizing and destruction of any books that may be deemed offensive to the government, and the arrests and imprisonments of any offensive writers, printers and publishers. Parliament failed to renew the Act in 1695 but what other laws were imposed on Britain’s at the beginning of the 17th century?

- Capital punishments for crimes including treason, piracy, forgery and arson in the Royal Dockyards still existed. What form of capital punishment one received depended on their social background.

- Beheading, which was not abolished until 1747, was normally reserved for those born into nobility.

- Being hung, drawn and quartered was the other more popular option; convicts were driven to the place of execution, hanged, and then whilst still alive (and sometimes conscious) had their stomachs cut open and their entrails drawn out.

- Women found guilty of treason or the murder of their husbands faced the prospect of being burned alive. But don’t worry; the executioner would often strangle the culprit before lighting the match.

- The execution of witches was still legal in England at the time. Unlike in other parts of Europe, those suspected of witchcraft in England were hanged for their crimes as opposed to burnt at the stake. The last execution of a witch was in in 1682, when Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards were executed at Exeter.

- Hollywood movies often depict criminals easily getting away with murder- it was even easier in 1695. Royal Pardons were still dished out for even the most heinous of crimes if the King knew the defendant or felt sympathy towards them. Women had it even easier, often ‘pleading the belly’ that they were with child, omitting them from any punishment until they gave birth. By then their sentencing was often forgotten about.

- Those who had been pardoned were then branded with a letter representing their crime on their thumb preventing them from being let off the hook more than once. For a short time this brand was scorched onto the face but as ex-convicts found they were increasingly unemployable the brand was moved back to the thumb.

- Those who committed petty crimes, including theft and felon, were sentenced depending on their social status, age, sex, and personality. Punishments ranged from imprisonment and committal to a house of correction, where hard labour was often inflicted, to public whipping and time spent in the stocks.

- As the use of the death penalty began to dwindle out at the end of the 17th century a new form of punishment was needed- many criminals soon found themselves transported to Australia.

- Suicide was still illegal in England at the time. Those found to have committed ‘self-murder’ were denied a Christian burial.

- Other laws of the time included a £2 fine for swearing (a lot of money in those times), the requirement of all Englishmen aged 17-60 to keep a longbow for regular archery practice and that all belonged to the Church of England.

This article was originally posted on 31 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

30 Oct 2013 | Events

Confirmed speakers:

Alan Rusbridger

in conversation with William Sieghart

David Davis MP

Sir Simon Jenkins

Jo Glanville

Tom Watson MP

RIBA

66 Portland PAce

London W1B 1AD

Monday, 4 November 2 0 1 3

6.4 5 – 9.0 0 P M

RSVP: [email protected]

Revelations about mass surveillance operations by the NSA and GCHQ have caused outrage in Europe, South America and the United States. There have been demonstrations and angry interventions by heads of state, and even President Obama concedes that a debate needs to happen. But in Britain protest and discussion are very close to being silenced.

The Guardian newspaper, which led the New York Times, the Washington Post and Der Spiegel in publishing material from the NSA leaks, is almost alone in believing that mass civilian surveillance is a matter of vital public interest. And now the British government, Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee, the intelligence agencies and even some sections of the media seek to isolate the Guardian and shut down the debate with claims that these disclosures aid terrorists and put national security at risk.

This must not be allowed to happen. This independently organised meeting at RIBA, on November 4, is called to support the Guardian’s reporting and to assert the right to a full national debate, involving all parties, about surveillance powers and the need to ensure

that the intelligence services work within the rule of law and are subject to genuine Parliamentary scrutiny and oversight. That is the only way for a democracy to react to revelations that affect everyone’s liberty.

Supporters include: Timothy Garton Ash (Oxford University and author of The File), Anthony Barnett (Cofounder Charter 88 and openDemocracy), Rory Bremner (Writer and performer), John le Carré (Author), David Davis (Conservative MP), Brian Eno (Musician and producer), Stephen Frears (Director), Alex Graham (Founder and CEO, Wall to Wall TV), Baroness Helena Kennedy QC (Lawyer and Principal of Mansfield College, Oxford), Peter Kosminsky (TV director and governor of BFI), Simon McBurney (Founder and artistic director, Theatre Complicite), Suzanne Moore (Columnist), Lord Pannick QC (Leading public law and human rights lawyer), Dr Elaine Potter (David and Elaine Potter Foundation), Philip Pullman (Writer), Richard Rogers (Architect), Ruthie Rogers (Chef), Philippe Sands QC (Leading human rights lawyer), Juliet Stevenson (Actor, writer and director), Neil Tennant (Singer-songwriter), Jimmy Wales (Founder, Wikipedia) and Sam West (Actor).

Also supported by the following organisations: Index on Censorship, Big Brother Watch, Human Rights Watch, openDemocracy, Open Rights Group, English PEN, The Manifesto Club, and Reprieve