30 Jul 2013 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

Free speech organisation Index on Censorship condemns the guilty verdicts in the trial of Bradley Manning. However, we welcome the verdict of not guilty to the charge of aiding the enemy.

Index Editor, Online and News, Sean Gallagher said:

‘Manning is a whistleblower who leaked files in order to inform the world about what really happened during the Iraq War to no personal gain. Index condemns this verdict and calls on the US government to abide by its duty to protect whistleblowers who speak out in the public interest. We urge the court to show leniency when sentencing Manning tomorrow.’

For more information and interviews, please contact Pam Cowburn, [email protected], 07749785932

30 Jul 2013 | Religion and Culture, Saudi Arabia

Raif Badawi, founder of the Free Saudi Liberals site, has been sentenced to seven years in jail and 600 lashes by a Jeddah court, according to a tweet from his lawyer Waleed Abu Alkhair yesterday

Raif Badawi, founder of the Free Saudi Liberals site, has been sentenced to seven years in jail and 600 lashes by a Jeddah court, according to a tweet from his lawyer Waleed Abu Alkhair yesterday

Badawi’s wife Ensaf Haidar, who now lives in Lebanon, confirmed the sentence to CNN’s Mohammed Jamjoom.

Badawi was arrested in June 2012 for “insulting Islam through electronic channels”. Abualkhair said the conviction was connected to charges of “insulting the religious police” and ridiculing religious figures in the kingdom.

In January, a court had refused to hear apostasy charges against Badawi, concluding that there was no case. Apostasy carries the death sentence in Saudi Arabia.

Among evidence against Badawi was an allegation that he had “liked” an Arab Christian page on Facebook. His lawyer believes he was pursued after calling for a “day of liberalism” in May 2012.

The court has also ordered that Badawi’s website be shut down.

30 Jul 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, Politics and Society, Slovakia

The Slovak Bar Association has demanded an apology for a political cartoon depicting them as pigs, saying it is defamatory and dangerous.

The Slovak Bar Association has demanded an apology for a political cartoon depicting them as pigs, saying it is defamatory and dangerous.

The cartoon shows a newly qualified lawyer receiving his diploma from another lawyer, both depicted as pigs, with the message “You’ve become a doctor of law. There is no better profession for looting/plundering of this country.”

“The Chamber does not want to interfere with the right to freely express your opinions in public and even in the form of cartoons, however, that freedom of expression must not unreasonably interfere with the rights of others or belittle them,” the Slovak Bar Association said in a statement.

They argue that the cartoon is dangerous speech, which defames a group of people based on their education.

The cartoon was by Slovakia’s most popular political cartoonist Shooty, whose real name is Martin Sutovec. It was published in Sme, one of the country’s biggest daily newspapers.

While freedom of the press is guaranteed by the constitution, this is not the first time the media freedom has come under threat.

In 2010, Shooty won a lawsuit filed against him by then Prime Minister Robert Fico, over a cartoon of a doctor telling him his back pain was non-existent as he was spineless.

In March this year, a verdict ordering Sme to publish three apologies or be fined €150,000 was upheld. This stemmed from an article about a member Slovakia’s Council of Judges, who was given a free hunting trip, which would constitute an illegal gift.

30 Jul 2013 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

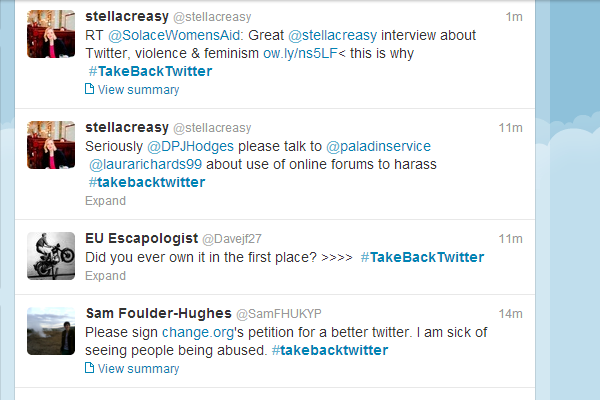

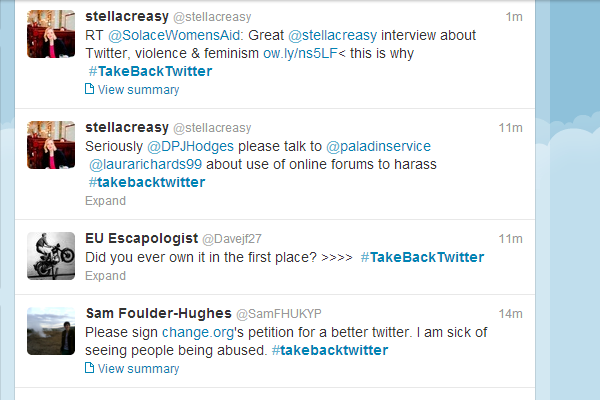

On a BBC Newsnight discussion last night, panelists were asked if they felt that a watershed moment had been reached in our attitude to misogynist abuse and threats on Twitter.

On a BBC Newsnight discussion last night, panelists were asked if they felt that a watershed moment had been reached in our attitude to misogynist abuse and threats on Twitter.

It certainly feels like a moment: The increasing pervasiveness of social media in UK public life, combined with a resurgent young feminist movement (aided by social media), has led to this tumult of voices. We all seem to agree that something should be done about threats of rape, such as the ones experienced by Labour MP Stella Creasey, but the question is what?

Twitter yesterday released a statement saying they would look into introducing a report abuse button under all tweets. This, the company pointed out, is in fact already available on the Twitter iphone app, and will soon be rolled out on Android and desktop.

But some see a danger in this: a report button, they suggest, could easily be abused. Celebrity users with a large amount of followers could, for example, get their fans to report critics.

Political opponents and human and civil rights activists could easily be marked as abusive by users. I can imagine, for example, that Index on Censorship’s account would repeatedly be reported as abusive by, say, highly co-ordinated pro-Bahraini government tweeters.

What are the alternatives? Writing for the Guardian, Index contributor Jane Fae says that the focus is too much on the potential solutions Twitter can provide and not enough on the existing laws in place. Earlier this year, the Crown Prosecution Service released guidelines on social media user prosecutions. Index greeted these as by and large sensible (interesting to note that these came about because of a feeling that there were too many prosecutions of social media users; though there is a distinction between generally offensive material and specific, direct, threats).

Jane suggests a mechanism for reporting threats to the police, rather than Twitter:

“By all means, let’s have a button – but one that delivers reports of online abuse directly to the local police force, a bit like a security alarm, and not just to Twitter.

This relatively simple solution doesn’t exist yet but I’m currently coding a mock-up of one for Everyday Victim Blaming (EVB), a not-for-profit organisation set up to help stop violence against women. Installed on your computer, the button would let you generate instant email reports, detailing online abuse and asking the police to investigate. It should also copy a report back to EVB or another campaign group. If the police really are swamped, that, in itself, is a thing – and may finally prompt politicians to ditch the soundbite and think a bit deeper on this issue.

Matt Flaherty, the prolific and interesting tweeter and blogger on free speech issues, brings the issue back to Twitter with his idea of a “panic mode” to help tweeters beleaguered by coordinated attacks:

“My solution to this problem would be for Twitter to introduce something like a panic button that would immediately but temporarily place one’s account into a state where all mentions are blocked except for those coming from the followers and following lists. Twitter could also allow the user to open a case and have mentions logged against that case to help Twitter to take action against those who violate the terms. Twitter could also perhaps warn users attempting to put the panicked account into a mention or reply. Perhaps they could ask for confirmation either within the stream or in an email. An alternative would be to actually disallow the creation of the mention or reply. A blocked account is currently not allowed to perform a reply but it can use a mention. The same rules might apply here. The mention would still not be seen.”

It’s an interesting idea, particularly for the kind of abuse Caroline Criado-Perez was subjected to: The campaigner was receiving 50 tweets an hour, suggesting a level of co-ordination. Flaherty’s proposal is a kind of advanced version of Don’t-Feed-The-Trolls, allowing a user to silence the angry mob directed at them.

The Daily Telegraph’s Marta Cooper (formerly of this parish), points out, however, that technological fixes are not the answer to societal problems:

“The offline world is still inhabited by some men who believe that women who voice an opinion must be put in their place. This is simply reflected and amplified online. Twitter did not create the misogynistic monsters that hurled grotesque tweets at Criado-Perez or send the same to other women on a regular basis; online platforms simply make it easier for these individuals to behave in appalling ways, and it is far harder to ignore published text than a hateful comment made by some Neanderthal in a pub.

“As with other societal problems, there is no quick fix – technological or otherwise – to something which has centuries’ worth of roots. It is far more valuable and worthwhile to expose hate for what it is and to debate why it occurs in the first place.”

Martin Belam makes a similar point here.

So what do we do? MPs have called Twitter executives to testify at the House of Commons: there is no doubt Twitter could have handled this better – the action of their New York based manager of journalism Mark S Luckie, blocking critical but polite UK voices, has been particularly unfortunate. No doubt the Twitter representatives will face demands from MPs to do something, and fast.

But we should be careful of quick fix solutions: the police are investigating the threats against Criado-Perez and Creasy; it is likely there will be prosecutions. This may seem frustratingly slow for some, but that is the pace of these things. The instant nature of social media means we often expect instant remedies for problems that are, as Ben Goldacre puts it, a little bit more complicated than that. Collective effort and thought on this should take precedent over the kind of kneejerk thinking about the web that too often dominates (see David Cameron’s “ban all the bad things” speech last week). We want the web to be free and diverse, but we also want the web to be, as much as possible, a positive experience for people. This is the challenge we face, and our reactions over the issues raised in the past few weeks could have consequences for years to come. Together we can make the web better, but we should be wary of attempts to make it perfect.

Raif Badawi, founder of the Free Saudi Liberals site, has been sentenced to seven years in jail and 600 lashes by a Jeddah court, according to a tweet from his lawyer Waleed Abu Alkhair yesterday

Raif Badawi, founder of the Free Saudi Liberals site, has been sentenced to seven years in jail and 600 lashes by a Jeddah court, according to a tweet from his lawyer Waleed Abu Alkhair yesterday The Slovak Bar Association has demanded an apology for a

The Slovak Bar Association has demanded an apology for a  On a BBC Newsnight discussion last night, panelists were asked if they felt that a watershed moment had been reached in our attitude to misogynist abuse and threats on Twitter.

On a BBC Newsnight discussion last night, panelists were asked if they felt that a watershed moment had been reached in our attitude to misogynist abuse and threats on Twitter.