3 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features

Chinese websites

In 2010 China shut down 1.3 million web sites with popular pages, such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, blocked. Three years later and China has employed over 2,000,000 people to monitor microblogging sites, a further clampdown on free speech in the country.

Having blocked major social media sites it’s not surprising that a large percentage of China’s hundreds of millions web users have turned to microblogging sites to offer up their opinions on society. Although the Beijing News stated that the monitors are not required to delete posts they view online they do gather data by searching for negative terms relating to their clients and compiling the information gathered into reports.

Weibo, China’s largest microblogging platform, has more than 500 million registered users who post 100 million messages daily. Postings on the website that criticise the Chinese government are often removed.

Global internet access

The internet is often taken for granted by those with regular and easy access to the online world. However, a staggering 4.6 billion people live without access to it; that’s around 68% of the global population. The number of internet users has grown by 566% since 2000 but considering the positive effects the internet can have on employment, communications and finances more of the world should have access to this valuable resource.

Africa has the poorest access to the internet; only 7% of total global internet usage comes out of the continent with, on average, 15.6% of the population using the internet.

YouTube

YouTube was bought by Google in 2006. Seven years later and localised versions of the video sharing site have been implemented in 56 countries, allowing for the content posted on to YouTube to be tailored specifically to the country it is serving. Although localising YouTube for specific countries can help with issues surrounding copyright, it also means that governments can block specific content from being uploaded and viewed on the website.

In Pakistan the online video sharing site has been banned since 2012. Google is looking to localise YouTube in the country, allowing the population access to the site, but only if the search engine makes it easier to block any blasphemous or objectionable content. Iran, Tajikistan and China are the only other countries with a block on YouTube.

India and the internet

India may be able to claim to be the world’s third largest internet user (behind the U.S and China) but that does not mean the country’s 74 million internet users have free access to the web. According to the Google Transparency Report, India leads the way in the number of take-down requests issued. Between July and December 2012 Indian authorities requested, without court orders, that 2,529 items be removed from the internet- a 90 percent increase from the first half of 2012.

In 2013 amendments were made to the Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines) Rules which stated, under Section 79 of the IT Act, that intermediaries had only 36 hours to respond to complaints or content deemed by regulators to be “grossly harmful” or “ethnically objectionable”. The clarification meant that this content does not have to be removed from the web, but failure to respond or acknowledge to the request within the short time frame, which does not take into account weekends or holidays, can result in a criminal procedure.

This article was posted on Jan 3 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Tunisia

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Tunisian privacy advocates are concerned about a new cyber crime investigative body: the Technical Telecommunications Agency (better known by its acronyms ATT or A2T).

The agency was created by the Tunisian government under decree 2013-4506 issued on 6 November. It is tasked with “providing technical support to judicial investigations into information and communication crimes” (article 2 of decree ).

As soon as the creation of ATT was made public, netizens expressed their concern of a comeback of the despicable Ammar 404 (nickname attributed to internet censorship and surveillance under the Ben Ali regime). Others described the newly established agency as “Tunisia’s NSA”.

“Fears about a Tunisian NSA are justified”, Douha Ben Youssef an internet freedom activist said.

“The ICT Ministry is justifying the existence of A2T the way Ben Ali justified the need for a control of information flow under the pretext of counterterrorism”, she adds.

Ben Youssef is also concerned about the lack of transparency and civil-society participation in drafting decree 4506.

“There was not a single multi-stakeholder debate about the decree while it was a draft”, she says.

While acknowledging the need to “monitor criminals and terrorists’ activities in this digital age”, Raed Chammem, a member of the Pirate Party shares Ben Youssef’s fears.

“The fact that this agency was dropped as it is with no external supervision, in a country with a history full of abuses in this field, is very suspicious”, Chammem said.

The decree is “too vague. It mentions cyber-crimes without providing a clear definition about the nature of these crimes or specifying them”, he added.

Tunisia does not have laws addressing cybercrime or clearly determining “ICT crimes” mentioned in the decree. This legal void could be problematic considering the country’s vague ICT legislation and repressive laws.

Article 2 of decree 4506 states that ATT is tasked with the “reception and processing of investigation orders… stemming from the judicial authority, in accordance with the legislation in effect”.

Without specifying “the legislation in effect”, users could be investigated and put under surveillance by the ATT under criminal defamation and insult laws.

“Judges do not assess the seriousness of putting certain types of internet content under surveillance”, Moez Chakchouk CEO of the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) told Index.

Despite the absence of a legal text requiring the agency to practice surveillance, ATI has been tasked with policing the Internet and assisting the judiciary to investigate cases of cyber crime amidst a legal and and institutional vacuum. Though, the establishment of ATT is set to bring an end to such tasks.

Chakchouk says that many of the surveillance court orders received by ATI after the revolution have nothing to do with cases of counter terrorism or national security but are rather related to defamation.

“A crime in the cyberspace is not defined within the meaning of the Tunisian law. A simple facebook post or a tweet could be considered as a serious crime by these people [judiciary]”, he said.

In 2012, the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) consulted ATI about a new surveillance agency. The ATI had suggested the creation of an independent and permanent committee tasked with responding to court requests and made up of judges and civil-society actors, ATI chief declared to Index.

ATI’s suggestions “had been completely ignored”, he said.

Under the current decree, ATT is far from being an independent entity.

The agency’s director-general and department directors are “named by decree on the proposal of the ministry of information and communications technology”, (articles 4 and 12).

While an oversight committee established by the decree “to ensure the proper functioning of the national systems for controlling telecommunications traffic in the framework of the protection of personal data and civil liberties”, is dominated by government representatives appointed from the ministries of ICTs, Human Rights and Transitional Justice, Interior, National Defense, and Justice.

Tunisia’s interim authorities have failed to introduce real reforms in order to cut ties with the surveillance abuses of the past. Before taking the step to establish a surveillance entity the priority should have been repealing the dictatorship era laws and legally consolidating personal data protection.

Last year, the National Authority for the Protection of Personal Data (INPDP), Tunisia’s Data Protection Authority, was working on a draft of amendments to the 2004 privacy law.

The proposed amendments’ aims were to consolidate the authority’s independence from government interference and make state authorities’ collection and processing of personal data without the consent of the authority not possible. But, to this date the amendments have not been voted on at the National Constituent Assembly (NCA).

“The government does not see these amendments as an urgent priority”, Mokhtar Yahyaoui head of INPDP told Index.

“Without reforms, the authority is incapable of conducting its role the way it should”, he added.

This article was posted on 2 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

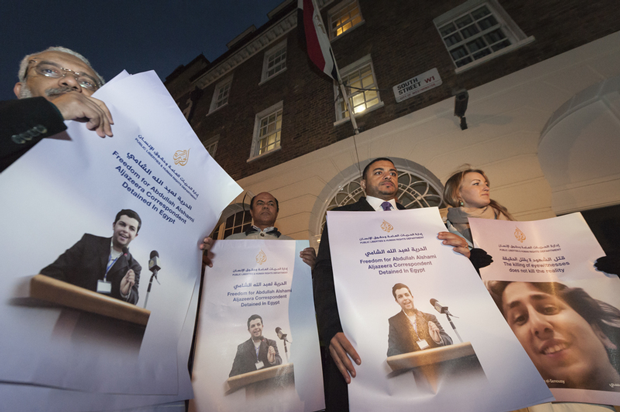

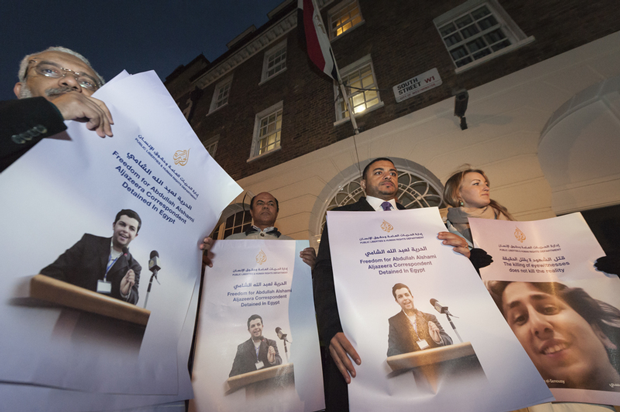

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

In a new sign of a regression in press freedom in Egypt, authorities have ordered three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English (AJE) channel held in custody for fifteen days.

The journalists –AJE Cairo Bureau Chief Mohamed Fadel Fahmy, award-winning former BBC Correspondent Peter Greste and producer Baher Mohamed–were arrested in a police raid on Sunday on a makeshift studio at a luxury Cairo hotel. They were charged with “belonging to a terrorist group and broadcasting false news that harms national security .”

Cameras and other broadcasting equipment were seized during the raid on the work room where the AJE TV crew had reportedly conducted interviews with activists and Muslim Brotherhood members on the political crisis in Egypt. A fourth member of the AJE team–Cameraman Mohamed Fawzy–was also arrested but was released hours later without charge.

The latest detentions raise the number of journalists affiliated with Al Jazeera and who are now jailed in Cairo , to five. Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah Al Shami was arrested on 14 August while covering the brutal security crackdown on supporters of toppled President Mohamed Morsi at Rab’aa–the larger of two encampments where pro-Morsi protesters had been demonstrating against his forced removal and demanding his reinstatement. Al Jazeera Mubasher Misr Cameraman Mohamed Badr was meanwhile, arrested on 15 July while covering clashes between security forces and pro-Morsi protesters in Ramses Square.

Al Jazeera has denounced the arrests of its staff members as an act designed to “stifle and repress the freedom of reporting by the network’s journalists.” The Egyptian government’s hostility towards journalists affiliated with the Qatari-based network has been prompted by what many Egyptians perceive as “a pro-Muslim Brotherhood bias in the network’s coverage of the events unfolding in Egypt”. Since the military takeover of the country in July 2013, at least 22 staff members have resigned from AJ Jazeera Mubasher Misr, the Egyptian arm of the network , over the alleged “bias in favour of the Islamist group”. Al Jazeera has however, denied the allegation.

The latest detentions are perceived by analysts as part of the crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood–the Islamist group from which the deposed President hails. Last week, the group was officially classified as a “terrorist organization” by the Egyptian authorities, in a move criminalizing the group’s activities, financing and membership .

The arrests of the AJE journalists have also raised fears among rights activists and organizations that the government crackdown was “widening to silence all voices of dissent”. Human Rights Lawyer Ragia Omran told the New York Times on Monday the charges are “part of a pattern of aggressive prosecutions–including conviction of protesters— that were rarely pursued even under Hosni Mubarak.” The New York-based Committee For the Protection of Journalists , CPJ, has also condemned the arrests, calling on the Egyptian government to release the journalists immediately . In a statement released by CPJ, Sherif Mansour, Middle East and North Africa coordinator , said ” the Egyptian government was equating legitimate journalistic work with acts of terrorism in an effort to censor critical news coverage.” In its annual census conducted last month, the CPJ ranked Egypt among the top ten jailers of journalists in the world with at least five journalists languishing in Egyptian prisons. It has also listed Egypt among the three most dangerous countries for journalists in the Middle East after Syria and Iraq . Six journalists have been killed in the country over the course of the past year, three of them while covering the bloody crackdown on Morsi’s supporters at Rab’aa.

Members of Mohamed Fahmy’s family meanwhile used his Twitter account to send a message on Tuesday reminding the government that “journalists are not terrorists.” His supporters meanwhile started a hashtag on Twitter calling for his release. Many of them expressed disappointment at what they described as “the government’s latest act of repression” warning that it would harm the government’s image much more than any amount of critical reporting would.

This article was posted on 2 Jan 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).