![Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/brazil-cover.jpg)

Read the full report in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Brazil is the world’s second-biggest user of both Facebook and Twitter, with already 65 million Facebook users and 41.2 million tweeters and counting. Up to 38 million new users are expected to join as smartphone prices fall and connectivity improves. The internet and social networks have allowed millions of Brazilian people to exercise their right to freedom of expression online. However, the internet came with strong inequalities. Digital access (people having access to the internet) and digital inclusion (people knowing how to use the internet) are a crucial component of the right to access to the internet, which is embedded in Marco Civil.

But Brazil’s socio-economic gap undermines access to the internet. Yet the country also has opportunities – both from the public and private sectors – to use the internet as a development tool in the country.

The internet and new technologies: lessening or deepening the socio-economic gap?

Brazil is the fifth most wired country in the world. The number of Brazilians with internet access in any environment (home, work, distance learning centres, internet cafes, schools) totals 105 million people or 52% of the population. Because of its growing internet penetration and mobile access to the internet, Brazil is a case where access to freedom of expression can be used as a development tool to combat poverty, discrimination and illiteracy (also see Index’s India policy paper: “India: Digital freedom under threat?”). The internet represents an opportunity to fill in the socio-economic gap that strongly divides Brazilian society – especially in terms of education, access to information, and access to freedom of expression. However, the country must first address the digital divide between those with and without access to the internet.

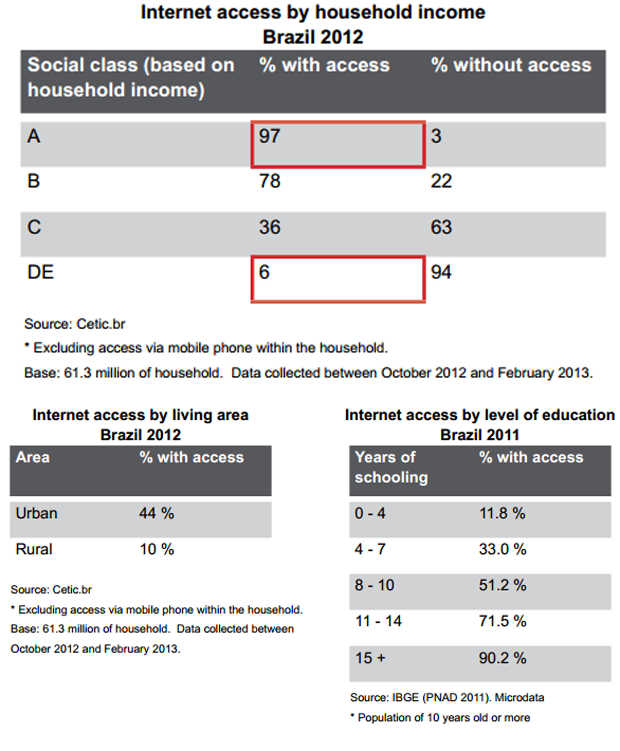

According to Cetic, the Brazilian Centre for Studies on Information and Communication Technologies, 97% of households from the high-income class (Class A) are connected to internet. This figure drops to 6% for households with inferior income, who represent 75% of the population (Class D-E). The gap between Class A and Class D-E speaks for itself but is not the only factor slowing down access to the internet. A study by the Brazilian Institute of Information Science and Technology shows that the differences in access among ethnic groups are large, and the differences between regions are also significant, as are the differences observed between educational levels. In light of the arguments involving the close relationship between digital division and social inequality, Brazil must address digital access as a priority critical for both the Brazilian economy and social inclusion.

Public and private initiatives have already been undertaken to provide greater internet access, faster broadband connections, and IT skills to vulnerable groups. For example, Digital Cities is a government initiative launched in 2011 by the Ministry of Communications that aims to provide full broadband telecommunications infrastructure and internet access to meet the needs of citizens, businesses and public bodies.[1] Digital Cities is a pilot project, which starts out with a selection of 80 municipalities.[2] The project aims to install public internet access points that will be accessible, free of charge and installed in densely populated areas. The project also anticipates the creation of distance learning centres, and the interconnection of all public buildings in the network.

Apart from the socio-economic divide that impedes citizens’ access to the internet, another challenge for Brazil is to provide internet access across its wide territory. The country occupies roughly half of South America. The National Broadband Plan (PNLB) launched by the Brazilian government in 2010 was created to ensure greater broadband access for low-income households across the country by installing fibre optic cables. However, the planned expansion of the national network covered mainly Brasilia and 25 state capitals, “ignoring” the northern region of the country. As a result of this unequal distribution, the “Broadband is your right!” campaign was launched to demand universal broadband service with a view to narrowing the digital divide. Indeed for some people living in remote areas – with limited geographical access to the main cities and without official mailing addresses, broadband access is the only way to be “connected”. Their email address is their only address. That is also true for people living in very poor urban areas – deprived of a physical mail address – such as the favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

One of the “Broadband is your right!” campaign’s proposals was that the former state-owned monopoly operator, Telebras, should offer universal broadband in order to provide access to the most remote areas. The campaign was not successful and then shifted its focus to quality standards of broadband connection, including guaranteed download and upload speed, connection stability and net neutrality at affordable prices. This time, the campaign was successful with Anatel – Brazilian Agency of Telecommunication – approving a number of the suggested criteria.

“The social media capital of the universe” and the emergence of mobile access to the internet[3]

23.3% of Brazilians use their phones to access the internet. As of mid-2013, Brazil was home to the largest mobile phone market in Latin America, and news organisation Reuters forecast that Brazil would become the fifth largest smartphone market in the world by the end of 2013. The surge in new smartphone users can facilitate the expansion of internet access for those who do not benefit from broadband at home. It can potentially offer an alternative solution to the difficulty of bringing broadband coverage to the entire country. However, while Brazil’s mobile phone market has more than doubled in six years to 272 million connections in a country of 200 million people, network investments have not kept up. The risk of an embarrassing World Cup outage is just one consequence of an explosion in mobile data use outpacing the growth of Brazil’s cell network.

38 million Brazilians are expected to be able to access the internet via their mobile phone by the end of the year 2014. As access widens, the push for proper regulation will grow. Marco Civil touches on privacy rights but has left a few grey areas in terms of data retention and government access to data. As more Brazilians connect to the internet and gain necessary computer skills and education about the benefits of the web, civil society is now pushing for stronger frameworks around privacy and data retention.

Article 4 of Marco Civil promotes “the right of access to the internet to all” and article 27 asserts that “public initiatives to promote digital culture and promote the internet as a social tool should: I) promote digital inclusion; and II) seek to reduce gaps, especially between different regions of the country, access and use of information technology and communication”. The debate surrounding the adoption of Marco Civil contributed to raising awareness on internet rights and made it a popular issue. The increase of Brazilian online users may increase demands for privacy, and could lead to more debates around free speech online and offence. How much it leads to demands for media freedom and free speech will depend on the debate about freedoms offline as much as online.

The full report is available in PDF: [English] | [Portuguese]

Part 1 Towards an internet “bill of rights” | Part 2 Digital access and inclusion | Part 3 Brazil taking the lead in international debates about internet governance | Part 4 Conclusions and recommendations

— Footnotes

[1] Citades Digitais. Building a cooperative and innovative ecosystem, Brazilian Ministry of Communication

[2] On 30 May 2014, Brazil’s Ministry of Communication added nine cities in the state of Bahia to its Digital Cities programme.

[3] Brazil: The Social Media Capital of the Universe, Loretta Chao, The Wall Street Journal, 4 February 2014, accessed 24 February 2014,