21 Mar 2014 | Campaigns, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Turkey’s late night decision to block Twitter last evening is emblematic of the increasing authoritarian tendencies of the prime minister Recep Erdogan.

Index condemns prime minister Erodgan’s move to block Twitter as censorship of which the worst authoritarian regimes would be proud.

Index CEO Kirsty Hughes said: “The degree of censorship in Turkey has gone from bad to very grave. Index calls on the Turkish government to restore freedom of expression in Turkey and to end its block on Twitter.”

She added:

“Index calls on the European Union to demand Turkey stops its attacks on freedom of expression – on social media, the broadcast and print media, and the right of assembly, or to suspend its membership negotiations.”

After weeks of threats against social media, the blocking of Twitter sends a clear sign that Turkey should no longer be accepted as even a talking partner for accession to the EU. Index calls on the EU to suspend all discussions with Turkey until the government takes steps away from censorship of its press and social media outlets.

Couched in terms that throw a thin veneer of legality and protection of public morals, the block against Twitter was either instituted at the behest of citizen complaints or court orders to remove content that were resisted by the social network. The government’s move against Twitter follows the leak of recorded conversations of Erdogan that are embarrassing to his administration ahead of local elections.

Twitter is an increasingly important tool in Turkey where it is used by more than 36 million internet users, of which 31 per cent use Twitter (according to eMarketer). As the election approaches, clearly the Erdogan government is worried about the power of social media to spread news and information it doesn’t want its people to know. It was expected that Twitter would a big part of the upcoming election strategy for all parties.

21 Mar 2014 | Awards, News

From upper left: Shahzad Ahmad, Rahim Haciyev, Shu Choudhary, Mayam Mahmoud. (Photos: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

This year’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2014 were awarded to a diverse group of remarkable individuals and organisation from the young female Egyptian Rapper to a Pakistani internet campaigner, from an Indian digital pioneer to an Azerbaijani newspaper.

The Freedom of Expression Awards 2014 took place this evening at the Barbican Centre in London and saw 18 year old, Egyptian rapper, Mayam Mahmoud win the Arts Award; Pakistani internet freedom fighter, Shahzad Ahmad pick up the Advocacy Award; Shu Choudhary, the Indian journalist who has created an egalitarian news platform receive the Digital Activism Award; and the Azeri newspaper, Azadliq, win the Journalism Award.

The Freedom of Expression Awards recognise the bravest journalists, artists and activists from around the world. From Edward Snowden to FreeWeibo and David Cecil to Colectivo Chuhcan, their remarkable true stories remind us that the right to free expression must be defended at all costs. Index is proud to bring these voices to London and shine a light on their work for the world to see.

Index Arts award: Mayam Mahmoud, Egyptian Hip-hop Artist

Mayam Mahmoud, Egyptian Hip-hop Artist, accepting her award (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

A finalist on Arab’s Got Talent, hijab wearing Egyptian rapper Mayam Mahmoud uses hip-hop to address issues such as sexual harassment and to stand up for women’s rights in the country that, after the hope of Tahrir Square, is slipping back into authoritarianism.

Google Digital Activism award: Shubhranshu Choudhary, Indian Journalist

Shubhranshu Choudhary at the Index awards (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Shubhranshu Choudhary is the brains behind CGNet Swara, a mobile-phone based news service that allows some of India’s poorest citizens to upload and listen to hyper-local reports in their own dialect, no smartphone required! CGNet Swara is both circumventing India’s strict radio licencing laws and creatively providing an outlet for those overlooked people on the wrong side of the digital divide.

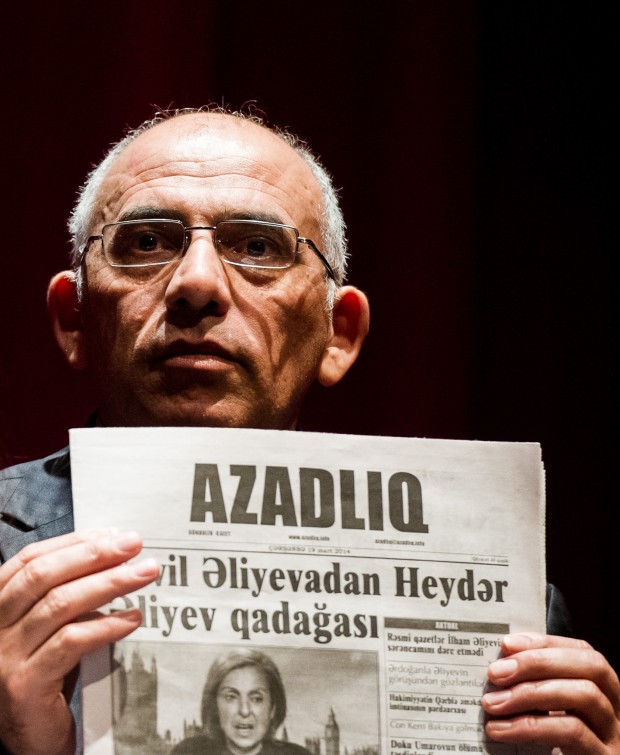

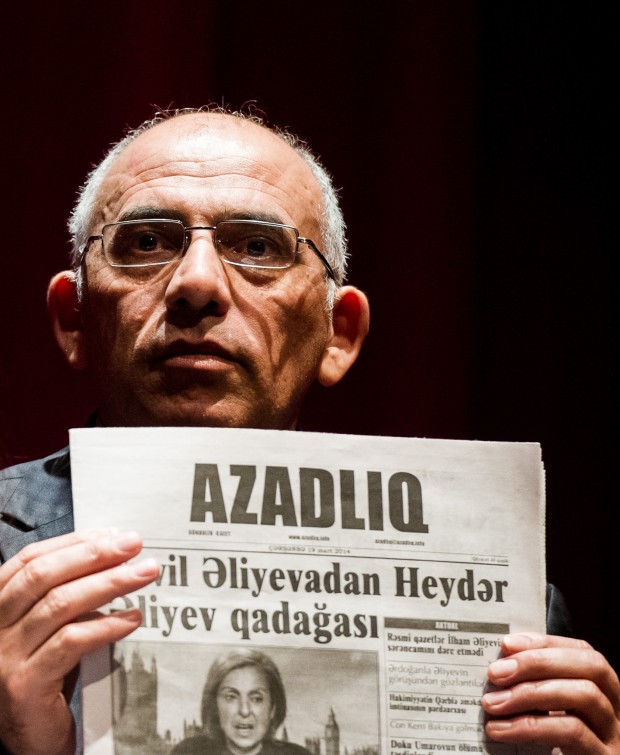

The Guardian Journalism award: Azadliq, Azerbaijani independent Newspaper

Rahim Haciyev, deputy editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

One of the last independent media outlets in Azerbaijan, Azadliq has continued to report on government corruption and cronyism in spite of increasing pressures and a financial squeeze enforced by the authorities.

Doughty Street Advocacy award: Shahzad Ahmad, Pakistani Campaigner

Shahzad Ahmad at the Index awards (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Shahzad Ahmad leads the fight against online censorship in Pakistan. He has sued the Pakistani government over their suspected use of surveillance software, FinFisher, and he is suing the government over its ongoing blocking of YouTube which is depriving his people of one of the world’s most popular video channels.

#IndexAwards2014: The Doughty Street Advocacy Award winner Shahzad Ahmad from Index on Censorship on Vimeo.

21 Mar 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News

(Image: Theo Schneider/Demotix)

Serbia is in the process of forming a new government. Following the Progressive Party ‘s (SNS) landslide victory in Sunday’s elections — securing 48% of the votes and 156 of 250 parliamentary seats — one man in particular holds the keys to the country’s future. Leader Aleksandar Vucic, Deputy Prime Minister in the previous coalition, is dropping the prefix and taking the top spot this time around.

While at 44, he would be a relatively young leader, he has had plenty of experience in high politics. Indeed, back in the 90s, he served as Minister of Information under Slobodan Milosevic. Many people spend their twenties trying figure out what to do with their lives. Vucic, meanwhile, was busy introducing a notoriously hardhanded media law, among other things, introducing fines to punish journalists and banning foreign media. As he now prepares to take office, should Serbia’s press be worried?

On the one hand, Vucic has worked hard to shift his image from hardline nationalist, to pro-EU reformer, his focus firmly fixed on Serbia’s struggling economy. He has gone after some of the country’s biggest financial criminals in a high-profile anti-corruption campaign. He has pushed for normalisation in the strained relationship with Kosovo, to put EU accession on track. On election night, the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed al Nahyan, could be found celebrating with Vucic at the SNS headquarters. The man who once said that 100 Muslims should be killed for every Serb, is securing loans in the billions from the UAE to help fund ambitious regeneration projects in Belgrade.

Yet, despite this apparent commitment to transparency, and despite claiming freedom of the media as one of his “five priorities” — his own personal regeneration, if you will — big words have not really translated into action when it comes to Serbian press freedom.

The country’s journalists have long been working under less than ideal conditions. From the direct, physical threats suffered under the Milosevic regime, to repressive legislation, free expression has been well and truly chilled. But the biggest challenge today is soft censorship, according to the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN).

“Press freedom in Serbia is mostly endangered by soft censorship meaning that it is mostly endangered by discriminatory and un-transparent allocation of state funding towards media outlets. This money is usually used to reward those who are in favor of the government and to punish those who oppose it. As opposed to direct threats, soft censorship is much harder to detect,” BIRN’s Tanja Maksic told Index.

“In [the] last year and a half of the Vucic and [former Prime Minister] Dacic government, we haven’t witnessed much of the determination to stop this undemocratic practice,” she adds.

Indeed, evidence points to the Prime Minister to-be doing the exact opposite. A recent report analysing election content on TV showed that the Progressive Party, and Vucic specifically, were favoured in the, overall strikingly positive, coverage. And back in February, a video adding satirical subtitles to genuine footage showing Vucic rescuing a boy from a snowstorm, was taken down. The video, originally from public broadcaster RTS, was removed over copyright infringement claims, despite campaigners arguing it did not break copyright laws. Authorities are widely believed to have played a part in the removal. A number of websites that had published it were blocked or attacked from within the country, while individuals behind the sites saw their social media profiles hacked. The claims made in the subtitles — that the whole report was staged to paint Vucic in a favourable light ahead of the elections — might have cut too close to the bone.

Vucic’s alleged control over sections of the Serbian media is perhaps most evident in the case of former Economy Minister Sasa Radulovic. Following his resignation, not long before the eventual collapse of the previous government, he was, without explanation, dumped from a popular TV talk show. The last-minute replacement? Aleksandar Vucic. Radulovic soon tweeted that he couldn’t wait to tune in to the evening’s show “to figure out why I resigned”. He followed this up by publishing an explosive resignation letter, accusing the government, including the anti-corruption crusading deputy prime minister himself, of corruption. He added that he’d been subjected to a “media lynching” by tabloids friendly to the government, that self-censorship is rife in Serbian media and that “news is being smothered”. The letter was covered by state-funded news agency Tanjug, but the report was removed within minutes and only republished following complaints.

Lily Lynch is the co-founder and editor of Balkanist, an independent online magazine covering, as the name suggests, the Balkan region. They have first-hand experience of Serbia’s restrictive media environment, once having their power cut for three days after publishing government leaks. She says Vucic has been “disastrous” for Serbian media, and believes that with his newfound, unchecked power they will see “more censorship”.

“I think that self-censorship will likely get even worse than it already is, as compliance with the status quo is often the only way to keep a job in Serbia,” she explains to Index. “Independent media outlets like Pescanik will be allowed to work because their audience is small and marginal, and their existence actually benefits Vucic because he can cite them as evidence that there is media freedom in Serbia. Meanwhile, the media that the majority of the country reads or watches will continue to depict Vucic as the savior of the nation.”

This depiction seems to have made an impact beyond Serbia’s borders too. Vucic’s pro-EU stance, and especially his perceived pragmatism regarding Kosovo, has boosted his international profile. He’s been labelled “the man bringing Belgrade in from the cold”, and American ambassador Michael Kirby has even praised Serbia’s media freedom.

It is, however, also worth noting certain cracks in this image within Serbia. The turnout figures of 53.2% — following the downward trend of previous elections — would suggest the adulation among the population is not as widespread as on first glance. The Facebook group “I did not vote for Vucic”, set up on election day, with its some 2,400 likes and counting, might point to the same.

Tanja Maksic says the real test for the Vucic government will come with adoption of much needed laws prescribing stricter control of media funding from public budget. If these are passed and implemented it “will be a clear demonstration of a new political will to pass the reforms in media sector,” she adds.

Lynch is not optimistic. She says there is a real danger Serbia could go the way of Hungary, a country that under the leadership of Victor Orban has witnessed the state of media freedom nosedive. She is not the only one to make the link. A recent Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty asks if Serbia “is headed for Orbanization”?

“Vucic has used the media as mouthpieces to denounce opponents, smearing them and accusing them of crimes without evidence. I definitely think this will continue. Others say “everything is up to Vucic now, he has no one to excuses anymore” but he has attained this level of power and will not let it go so easily. Anything that goes wrong will be the fault of some minister or other, who will be sacked and humiliated in the press so that Vucic is not viewed as responsible in the eyes of the public,” Lynch says.

“Vucic’s arrests and “anti-crime crusade” has made many public persons, including journalists, very afraid.”

This article was posted on 21 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Mar 2014 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Singer Nancy Ajram is among those whose videos have been banned by Egypt’s censorship committee.

In a move that has sparked concern among Egyptian secularists, the country’s censorship committee this week banned 20 music videos allegedly containing “heavy sexual connotations” and featuring “scantily-dressed female singers and models.”

The decision to ban the video clips deemed “inappropriate” and “indecent” by members of the state censorship committee, comes two months after a new constitution guaranteeing freedom of expression and opinion was approved by 98 per cent of voters in a national referendum. The new charter replaced the 2012 constitution, widely criticized by rights organizations and revolutionary activists as an “Islamist-tinged” document.

The majority of Egypt’s secularists who celebrated the ouster of Islamist president Mohamed Morsi in Tahrir Square in July had feared that the Muslim Brotherhood –the Islamist group from which he hails –was seeking to alter Egypt’s ‘moderate’ identity. The Islamist group has since been outlawed and designated a terrorist organization by the military-backed authorities that replaced the toppled president.

The banning of the video clips comes amid heated debate on “raunchy” music videos broadcast on some of the Arab satellite channels. In recent years, an increasing number of popular Arab female singing-stars have challenged social norms and broken cultural taboos by revealing more flesh in their video clips. The trend has stirred controversy in Egypt’s deeply conservative Muslim society with many Egyptians rejecting what they describe as “the pornification of pop music”. They insist that the “graphic, semi-porn sexual scenes featured in some of the music videos are not in line with Islamic tradition and culture”.

“Some of these video clips are more porn than music. We can hardly understand the lyrics; They are an insult to Arabic music and culture,” said Amina Mansour , a Western educated 30 year- old Egyptian freelance photographer.

It is no surprise that some liberal, westernised Egyptians agree with ultra-conservative Muslims in their society that the videos should be banned. Egyptian society–once a melting pot of different cultures has grown more conservative in the last 30 years. In his book Whatever Happened to the Egyptians, Economist Galal Amin blames the growing conservatism in the country on the introduction of Wahhabism –a more rigid form of Islam practised in Saudi Arabia and adopted by the millions of Egyptian migrants who travelled to Gulf countries after the oil boom in the seventies, seeking higher-paid jobs. The gradual transformation from a diverse, open and tolerant society into today’s conservative and far less tolerant Egypt is evident in the style of dress, behaviour and speech of many Egyptians. An estimated 90 per cent of women wear the hijab-the head covering worn by Muslim women -while the niqab, a veil covering the face , has become more prevalent in recent years.

Some analysts believe the trend of conservatism, which had steadily grown in Egypt recent decades, now appears to be regressing. A growing number of women and girls are removing their Islamic headscarf —once adopted as a political statement against the authoritarian regime of Hosni Mubarak and against Western-style values imposed on the society. Leila el Shentenawy, a 31 year old lawyer told Index she removed her veil after Morsi’s ouster to express her disappointment with Islamist rule.

“Morsi failed to deliver on promised reforms,” she said, adding that she and other liberal Egyptians were alarmed by the calls made by some hardline Islamists to bring back female genital mutilation and lower the age of marriage for girls.

“We were becoming a backward society instead of moving forward,” she said.

Shentenawi however, supports the ban on the video clips, arguing that such videos are “commercialization of women’s bodies and a downright insult to women.”

Other Egyptians have meanwhile expressed disappointment over the banning of the video clips, perceiving the move as “a reversal of the democratic gains of the January 25, 2011 Revolution” that toppled autocratic president Hosni Mubarak and the subsequent uprising against Islamist rule in June 2013.

“We had two uprisings for freedom and a modern, democratic society,” lamented 26 year-old graphic designer Amr El Sherif. “The video clips are popular with young Egyptians and the latest ban can only be considered as a means of stifling free artistic expression.”

In January, Egyptian TV imposed a ban on several video clips reportedly containing “seductive scenes”, deciding they were”inappropriate for viewers”. The ban on the music videos featuring Middle Eastern pop idols Haifa Wahby, Alissa, Nancy Agram and Ruby among others, came in response to complaints by some viewers that the “hot scenes” depicted in the videos were “provocative” and “went against the morals of Muslim society.”

While modest by Western standards, “the gyrations and revealing costumes featured in the videos were too sexy for Arab audiences”, the censors decided. The ban is a continuation of the ultra-conservative trend started by Islamists during their one year rule when some of their lawmakers had complained to Parliament (then dominated by Islamists) that “Egyptian performer Ruby’s pelvic thrust dance moves and bare midriff were too much,” warning that the “obscene scenes” depicted in the music videos would “trash the taste of Egyptians.”

The ban of the videos meanwhile, coincided with the sexual assault of a female student by a mob on Cairo University’s main campus on Monday–the first violence of its kind on an Egyptian university campus. While condemning the assault incident in a telephone interview broadcast on the private ONTV channel later that evening, University President Gaber Nassar implied the victim was to blame, saying her “immodest attire” had invited the assault. He urged students to dress modestly, adding that those who do not follow the university’s regulation would be barred from entering the university campus by security guards.

Some Egyptians believe that the “suggestive” and “explicit” music videos are partly to blame for a surge in incidents of sexual harassment and violence against women in the country since the January 2011 uprising.

“Sexual frustrations of youth –many of whom are unemployed and unable to afford the cost of marriage– are being fuelled in part by sexy music videos and other pornograhic material on the internet, causing unruly behaviour by some youth,” Said Sadek, a Cairo-based Political Sociologist and activist, told Index.

The recent ban on the video clips also comes hot on the heels of an International Women’s Day protest-rally staged by nude Arab and Iranian women in the Louvre Art Museum’s Square in Paris, calling for “equal rights” and “secularism” in their respective countries. Egyptian internet activist Alia Al Mahdi was among the participants in the Paris nudist rally which organizers said, was held to “highlight the many legal and cultural restrictions imposed on women in the Arab World”. El Mahdi had also protested naked outside the Egyptian Embassy in the Swedish capital Stockholm in December 2012 to express her opposition to what she called Morsi’s “Sharia Constitution.” Raising the Egyptian flag, she had the words ” No to Sharia” written in bold print on her naked body.

Many of the revolutionary youth-activists who led the uprisings in Tahrir Square in January 2011 and June 2013 had hoped the downfall of two authoritarian regimes would usher in a new era of greater freedoms including freedom of expression and opinion.But their hopes are fading fast amid increased restrictions and a climate of growing repression.Despite the challenges, they vow to continue to push for “reforms” and “a more liberal Egypt”. While many of the revolutionaries say they oppose Alia Al Mahdi’s method of protest, perceiving it as ” extreme”, they insist ” there is no going back to repression and censorship by the authorities.”

“We’ve had our first taste of freedom with the revolution three years ago and once you’ve had that, you can only move forward and never look back, ” said Mohamed Fawaz, an activist and member of the April 6 Movement, one of the two main groups that mobilized protesters for the January 11 mass uprising. Meanwhile, the battle between secularists and conservatives for the soul of the “new Egypt” continues.

This article was posted on 21 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org