4 Nov 2014 | ArtFreedomWales, Events

At the end of Index on Censorship’s ArtFreedomWales’ second online discussion (watch it in full above) there was a general consensus that they were just scratching the surface of a huge, important subject.

Hosted by Bethan Jones Parry (Broadcaster, Journalist and Writer), the following met online to discuss the opportunities and obstacles to expression for artists working in Welsh:

- Mari Emlyn (Artistic Director Galeri, Caernarfon)

- Arwel Gruffydd (Artistic Director Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru)

- Bethan Marlow (Playwright and Storyteller)

- Iwan Williams (Independent Creative Producer and Creative Development Officer for Mentrau Iaith Cymru)

The live broadcast opened with Jones Parry asking what censorship meant to each individual? Williams kicked off by saying he felt that culture in Wales isn’t censored from the outside but rather from the inside – self-censorship. Emlyn agreed that self-censorship is what she is most aware of despite there being examples of censorship in everyday life. To her censorship is stopping or restricting opinion and the spreading of that opinion. Marlow expressed, although not sure if it is censorship entirely, that when writing in Welsh there is a pressure and an awareness that the whole audience must be taken in to consideration and that you must please the whole audience. It is not confined to the theatre alone. Working within the Welsh language and trying to appeal to everyone can affect the work that is created and dilute it in some way. Jones Parry asked Gruffydd if he had a free voice as Artistic Director of Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru or is his voice censored. Gruffydd answered by saying that he hopes the company is giving writers and artist an uncensored voice however that there is a sense of self-censorship amongst writers and artists when working in Welsh especially with those who work bi-lingually. He noted two examples. One writer saying he didn’t want to write for the Welsh theatre because he had nothing to say about Wales – leading to the question must writing in Welsh be about writing about identity? The other example, a playwright who didn’t want to express themselves in Welsh because they had too much respect for the Welsh audience. They didn’t want to offend by disclosing some of the things lurking in their head! “Something’s are more difficult to share in Welsh.” Jones Parry concluded from the initial response that censorship is a very interesting mixture but what is apparent, despite there being an inherent censorship by any state regarding culture, in Wales, censorship mostly comes from self-censorship.

Jones Parry moved on by quoting David Anderson, Director General of National Museum Wales. “We are in the second decade of the twenty first century, but we still retain the highly centralized, nineteenth century, semi-colonial model that the arts should be concentrated in London, and that funding London is synonymous with serving the English regions and the nations of the UK. For Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland this undermines the principle, embedded in law, that culture is a devolved responsibility. It is a constitutional tension that remains unresolved.” The panel were asked to respond. Williams agreed that the funding model is centred on London and Cardiff and that there is always a pull towards the cities but that it was up to the companies and artists to change things – the ethos being to create the quality of work created in London in small rural areas of Wales. Jones Parry asked if the budget is less is it possible to achieve and offer the same quality? Williams agreed that budget is a huge factor but that confidence is a factor too. “We need to be ambitious and take big strides with our projects. By being ambitious, and if the will is there, we can create something that is of the same quality as anywhere else in the world.”

Responding to the question ‘Do Welsh speakers suffer, budget wise, because there are fewer Welsh speakers than English speakers?’ Gruffydd expressed “If you want to explore and experiment and strive towards new things with work and text – in a larger environment, with more people aware and more people buying a ticket that funds the work then a momentum is created. It is very difficult to express yourself in Welsh if your ideas are a little leftfield because we are a small audience when we are a full audience. If we break it down again to experimental work, certain texts, creating projects that appeal due to their nature then we are performing to two people and their dog. It’s difficult to fund that work.”

Marlow was asked how her work is perceived away from Wales to which she noted that the same recognition did not exist. Work away from Wales for her has always been an invitation from a company and not bringing previously performed work in Wales to England. She shared her frustration on searching for an agent that despite having many Welsh language credits including productions for high profile companies such as Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru, Sherman Cymru and TV companies, it was difficult to gain interest away from Wales. She believes the same gravitas for these big companies in Wales did not translate away from Wales. However, she believes “ as artists we don’t treat our companies with the same gravitas either. It’s important we have that pride of working in Wales and change our attitudes to see that a play produced by Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru is just as impressive as having work produced in London.” Jones Parry questioned that as a nation working in Welsh did our insecurity lead to self-censorship? Williams stated “Historically the language has been trampled on over the years. Our confidence as a nation is low. Since devolution there is a new sense of confidence and pride but a lot of work to be done still for us to believe in ourselves. It takes time and it’s not done overnight but we need to share big ideas and say big things.” Williams notes too that the creative sector in Wales is small and everyone knows each other. The critique of the work that happens in larger cultures doesn’t exist in Wales. “We censor the work we create as well as censor what we say about other people’s work.” Emlyn agrees. “As a small nation we are all afraid to offend. We all know each other. “ She believes that we must reach a point where we overcome the fear of offending. “There is a tendency to write safe things that doesn’t cause a stir or uproar. Conversation and interest is good. It gives us the drive to push boundaries and create something a bit more daring. Criticism is a problem in Wales. Either the fear of insulting or reviews become extremely personal.” Emlyn believes that there isn’t enough theatrical and historical background by theatre reviewers in Wales. She claims poetry and literature reviews are much stronger within the Welsh language.

Leading on from this, Gruffydd was asked as a director if he censors himself and compromises his principles by producing work that is popular and provides bums on seats. Gruffydd stated it is difficult to rate how much he censors himself. He has his own view and leaning as a director that reflects his personal artistic leaning, opinion and politics despite trying to remain impartial. During his tenure as Artistic Director of Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru he has chosen plays and texts that have pushed the boundaries for example ‘Llwyth’ (Tribe – about a group of gay male friends in Cardiff). Marlow rejected Jones Parry’s assumption that there are times she has wanted to express something but didn’t as it wouldn’t allow her to make a living. As a writer she has always said what she wanted. She can’t write if it is fueled by a fee alone. Marlow feels lucky to have been supported by companies that have allowed her to be open and to share what she wants to express. She believes nurturing a relationship is important. “Wales is different to the rest of Britain. The work is different and what is being said is different and that people in Europe can identify with the work.” Gruffydd believes that the English censor Welsh language work more than other cultures, due to, in his opinion old preconceptions. He notes that English culture needs to check on their perspective of Welsh work and Welsh culture. As a company it was easier for Theatr Genedlaethol to attract an audience in Taipei than London. “There is a lack of preconception abroad. It would be difficult to sell a production in Welsh to a non-Welsh audience in Cardiff let alone London and yet in Taipei the play ‘Llwyth’ attracted an audience of 1000.”

Emlyn was asked if it was difficult to attract work from across the border and overseas to Galeri in Caernarfon, North Wales suggesting that geography takes a practical hand in censorship. Emlyn didn’t believe so. Galeri has established itself as a strong centre with a mixed programme. Work from elsewhere has inspired local performers. As an example Emlyn explained how a visit from Sadler Wells company, ‘Company of Elders’ inspired a collective of women over sixty, who felt they had no platform to express themselves, to create a dance piece at Galeri. Emlyn notes it is not just geography but age, illness and so on that can lead to censorship and people feeling frustrated and restricted and therefore censored. Remaining on the subject of geographical censorship Gruffydd stated that ‘every road does not lead to Cardiff.’ As a National company he feels it’s important to invest in communities and supply them with important and substantial productions and not focus specifically on the main centers alone. The company’s latest production ‘Chwalfa’ will only play at Bangor. “It is up for the audience to travel to experience the story of that specific community.”

Jones Parry was interested to know if the story of the non-Welsh speaking Welsh was being heard within the arts and if it was balanced with the Welsh language Welsh story. Marlow’s opinion was that having two National Theatre Companies proves the output is balanced and her experience of working extensively with Welsh speaking and non-Welsh speaking communities in Wales also proved that. She believes both have a strong presence and voice. Emlyn noted that Welsh language productions sell out at Galeri but it is very difficult to attract an audience to English language theatre if the productions are from Wales or beyond. She believes that a Welsh language audience trust what they will get from Welsh language companies and play it safe. She was unsure why as if someone had a genuine interest in theatre surely they would attend productions in any language?

Bringing the discussion to a close Jones Parry asked all panellists for their final word. Gruffydd finalised his thoughts by stating that every culture censor themselves. “Culture on the whole has always favoured the middleclass and educated. People who do not fit in to this assumption or norm don’t feel as secure expressing themselves because of fear. It is a challenge for us in the arts to help overcome this and give a wider geographic the voice to express themselves artistically. The arts should belong and be beneficial to everyone’s everyday life.” Marlow ended her contribution by urging Wales to be brave and stop comparing themselves to any other country. Williams concluded by saying that culture and the arts need to be taken to the communities in order for attitudes to change. “Attitude needs to change and will change by sharing towards culture and the language.” He strongly believes communities are the key and to invest in public work beyond the usual paths of theatre and TV. Emlyn ended by stressing that Wales shouldn’t be scared of venturing. “The arts are there for us to express ourselves. If we can’t express ourselves in the arts where can we? We have the right to fail. Only by failing do we learn. We shouldn’t be afraid.”

Follow and participate in the discussions @artfreedomwales.

Find out more about Index’s UK arts programme.

This article was posted on November 01, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Nov 2014 | Latvia, News and features, Religion and Culture, Russia, United Kingdom

Protest outside the Royal Albert Hall in London over the recent concert staged by Russian singer Valeriya (Photo: Lensi Photography/Demotix)

At first glance, there seems to be little that Latvia’s New Wave music festival and London’s iconic Royal Albert Hall would have in common.

The former is hugely popular contemporary music festival and talent spotting contest on the shores of the Baltic Sea, attracting thousands of revellers from Eastern Europe and beyond. The latter is one of the world’s most famous venues, where some of the global music industry’s biggest and best artists regularly perform. It is also home to the Proms, the premier musical event of the British establishment.

But both have recently been embroiled in the fallout from the crisis in Ukraine, as a culture war between Russia and the west threatens to widen.

Last week it was claimed by Russia’s culture minister that the New Wave festival was on the verge of being cancelled and moved to Russia after three of the headline acts were barred by the Latvian government earlier this year.

The New Wave festival in the town of Jurmala was due to see Oleg Gazmanov, Joseph Kobzon and Alla Perfilova, known as Valeriya, perform in July.

According to the Baltic Times, the trio were banned from attending by the Latvian foreign ministry over their pro Russian views on the Ukraine crises. At the time several members of the Russian State Duma called on the festival to be moved to another Russian seaside resort, and suggested Crimea as an alternative.

“Concerning the organisation of ‘New Wave’ in Crimea, we are ready to cooperate and will gladly host any creative project in Crimea,” Crimea’s Culture Minister Arina Novoselskaya was quoted as saying.

But Russia’s Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky has reopened the debate by suggesting that the festival is now on the verge of being moved permanently.

“This decision by the Latvian powers that be can be regarded with nothing except astonishment, and as a result, Jurmala stands to suffer serious economic losses,” he told the Baltic Times while at a private meeting in the capital Riga. “We are very close to making the decision to exit, because Russian artists will not tolerate such a slap in the face.”

The six day concert, which gives emerging artists around the world a chance to perform in front of large crowds, was started in 2002 and is considered one of the best in the region. Thousands attend the event and prizes for the winners can be in their tens of thousands of euros.

But big stars attend too.

Kobzon – once dubbed “Russia’s Frank Sinatra” and who is now a Russian MP – said that he was going to file a lawsuit at the European Court of Human Rights over his ban. “I’m suing the Latvian government for moral and material damages,” he told Pravda. “I had paid the hotel 11,500 euros for the time of my stay in Jurmala, but the hotel did not return the money to me.”

The Latvian foreign ministry released a statement at the time that said the three singers “through their words and actions have contributed to the undermining of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Latvian Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkevics sent a tweet that “apologists of imperialism and aggression” would be denied entry into Latvia for the festival. The tweet appears to have been deleted.

The issue has once again raised its head after a campaign was launched by anti-Putin activists to have several Russian artists banned from performing in the UK too. Both Kobzon and Valeriya, who were billed to play at a special one-off concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 21 October, were again targets of the proposed bans.

According to The Guardian, both artists signed an open letter supporting Putin’s controversial policies in Ukraine. In the week running up to the concert, Valeriya was pictured sitting next to Putin at the Russian F1 Grand Prix.

The London concert went ahead, though it would seem, not exactly as planned. Kobzon reportedly decided to not attend at the last minute, allegedly fearing he would be turned away at the UK border. Over 100 Ukrainian activists picketed the concert, holding placards that read: “Ukrainian Blood on Putin’s Hands” and “Valeria [sic] and Kobzon: Putin’s Voices of War and Death”.

“After the concert we asked some of the people who attended what was said, as they were leaving. They told us Kobzon didn’t perform, “Nadia Pylypchuk, from the London Euromaidan campaign group who organised the protest, told Index on Censorship. “Valeriya told them on stage that Kobzon couldn’t be there because of ill health. But a few days later he performed in Eastern Ukraine. He was just scared that he would not be allowed into the country,” she added.

Despite several attempts by Index to contact the Royal Albert Hall, the venue declined to answer questions about the concert, including whether Kobzon had performed.

A week later, Kobzon, who was born in the Donbass region, would be banned from entering Ukraine by the Kiev government. He nevertheless returned through the porous Russian border, which the Kiev government has little control over, to perform a concert at the Donetsk Opera House.

According to Buzzfeed he was joined on stage by rebel leader Alexander Zakharchenko for the Soviet classic I Love You, Life. Although Zakharchenko was clearly a little rusty. “It’s fine,” Kobzon reassured him after the performance. “I’m an even worse soldier than you are a singer.”

For activists back in the UK, the London concert was proof that Russia’s elite preaches one message to his home audience, whilst acting very differently abroad.

“Such hypocrisy is unacceptable,” Andrei Sidelnikov, an anti-Putin activist who has been given political asylum in the UK and who started the campaign to have the concert scrapped, told The Guardian. “In Russia, they declare that western values are bad, wrong, and not suitable for Russia. Then they travel to western countries to earn money, spend holidays, and buy real estate.”

This article was originally posted on 3 November at indexoncensorship.org

2 Nov 2014 | Campaigns, Russia, Statements

Aleksandr Bastrykin

Head of the Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

The Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

105005, Russia, Moscow, Technicheskii Lane, 2

Sunday 2 November 2014

Dear Mr Bastrykin,

RE: Request for investigation into the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev to be transferred to the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

On the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists (2 November) we, the undersigned organisations, are calling upon you, in your position as Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to help end the cycle of impunity for attacks on those who exercise their right to free expression in Russia.

We are deeply concerned regarding the failure of the Russian authorities to protect journalists in violation of international human rights standards and Russian law. We are highlighting the case of Ahkmednabi Akhmednabiyev, a Russian independent journalist who was shot dead in July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. In his work as deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, Akhmednabiyev, 51, had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

His death came six months after a previous assassination attempt carried out in a similar manner in January 2013. That attempt was wrongly logged by the police as property damage, and was only reclassified after the journalist’s death. This shows a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection. The journalist had faced previous threats, including in 2009, when his name was on a hit-list circulating in Makhachkala, which also featured Khadjimurad Kamalov, who was gunned down in December 2011. The government’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the State’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey).

A year after Akhmednabiyev’s killing, with neither the perpetrators nor instigators identified, the investigation was suspended in July 2014. As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such action sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia. ARTICLE 19 joined the campaign to have his case reopened, and made a call for the Russian authorities to act during the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014. During the session, HRC members, including Russia, adopted a resolution on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

While the Dagestani branch of the Investigative Committee has now reopened the case, as of September 2014, more needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation. We are therefore calling on you to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

Sadly, Akhmednabiyev’s case is only one of many where impunity for murder remains. The investigations into the murders of journalists Khadjimurad Kamalov (2011), Natalia Estemirova (2009) and Mikhail Beketov (who died in 2013, from injuries sustained in a violent attack in 2008), amongst others have stalled. The failure to bring both the perpetrators and instigators of these attacks to justice is contributing to a climate of impunity in the country, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

Cases of violence against journalists must be investigated in an independent, speedy and effective manner and those at risk provided with immediate protection.

Yours Sincerely,

ARTICLE 19

Amnesty International

Albanian Media Institute

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

Azerbaijan Human Rights Centre

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Center for National and International Studies (Azerbaijan)

Civic Assistance Committee (Russia)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Committee to Protect Journalists

Glasnost Defence Foundation (Russia)

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute (Lithuania)

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Memorial (Russia)

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

International Youth Human Rights Movement

IREX Europe

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Kharkiv Regional Foundation – Public Alternative (Ukraine)

PEN International

Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

The Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims

World Press Freedom Committee

cc.

President of the Russian Federation

Vladimir Putin

23, Ilyinka Street, Moscow, 103132, Russia

Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation

Yury Chaika

125993, GSP-3, Moscow, Russia

st. B.Dmitrovka 15a

Minister of Justice of the Russian Federation

Alexander Konovalov

Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation

119991, GSP-1, Moscow, street Zhitnyaya, 14

Chairman of the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights

Mikhail Fedotov

103132, Russia, Moscow

Staraya Square, Building 4

Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

Edward Kaburneev

The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

367015, Republic of Dagestan, Makhachkala,

Prospekt Imam Shamil, 70 A

Ambassador of the Permanent Delegation of the Russian Federation to UNESCO

H. E. Mrs Eleonora Mitrofanova

UNESCO House

Office MS1.23

1, rue Miollis 75732 Paris Cedex 15

1 Nov 2014 | Draw the Line, Events, United Kingdom

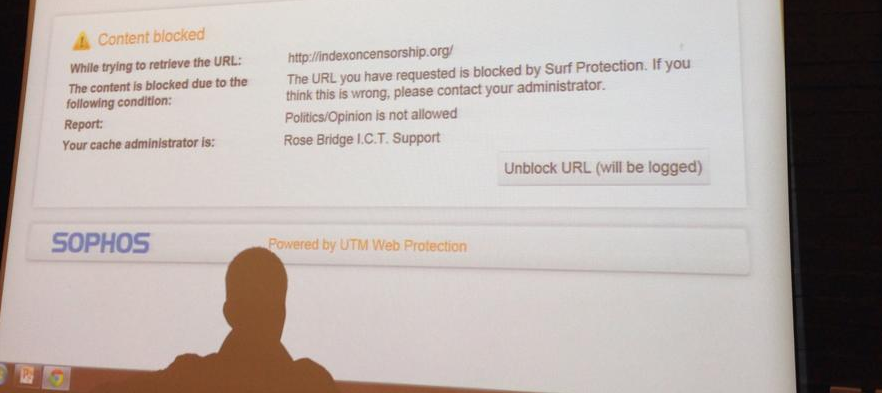

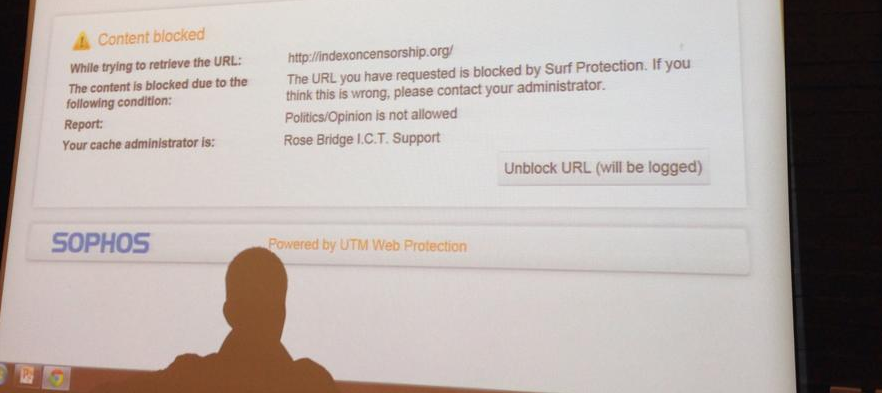

Index held a successful workshop with the north west contingent of the British Youth Council, despite the inability to access our own website because of internet filtering at the location.

Index held a third Draw the Line workshop with the British Youth Council, but this time with its groups in the north west of England at their regular regional convention. Before the workshop began we faced a problem — we couldn’t get onto our website. The convention was held in a local secondary school and the school’s server was blocking our website. This is unusual, but with highly sensitive school internet filters it was possible that there were too many words deemed unsuitable for children used on our website. This filter appeared to be more sophisticated and specified the reasoning behind blocking our content: “Politics/Opinion is not allowed”.

It was difficult to test how far this stretched, but it was alarming that politics or opinion would be blocked at a school limiting its pupils’ ability to research different points of view.

We spoke to youth workers at the convention who said they faced similar problems when trying to do projects with young people on LGBTQI issues or drugs. The filters were so sensitive that they would not even allow students access to the websites of support groups which cover these issues, it simply blocked them all.

Despite the censor’s best efforts this made a great starting point for the debate and demonstrated to the participants the levels of censorship that we all face in our daily lives. The groups were able to articulate many different current and historical instances of censorship from wartime propaganda to being forced to wear a school uniform and understood why freedom of expression is fundamental to human rights.

The discussion moved onto the latest Draw the Line question, “Are voting restrictions a violation of human rights?” The members enthusiastically debated the prospect of voting at 16 (this is one of the British Youth Council’s campaigns) with the group still split on whether this should be implemented into UK law. There was also a great opportunity to discuss these issues with the youth workers in the region and find out how social media restrictions can both harm and protect children and how we can begin to define the difference.

Wigan pier is one of the unique locations around the world where the Index on Censorship magazine is available to download for free. It was nominated as a free speech spot because of George Orwell’s novel, The Road to Wigan Pier. Find out more on how to download your copy here.

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org