26 Sep 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

Before the cancellation of Exhibit B at the Barbican this week, Index published an article from associate arts producer Julia Farrington in which she addressed the role of the institution in managing controversial art and a lack of diversity in arts management in the UK. Those who read the article following the cancellation and our short comment on it have interpreted our stance as one that in some way excuses or condones the protesters and the cancellation of the piece. This was certainly not our intention, but we realise that by failing to publish a detailed article or statement on the cancellation, we muddied our position.

So let’s be clear. People have every right to object to art they find objectionable but no right whatsoever to have that work censored. Free expression, including work that others may find shocking or offensive, is a right that must be defended vigorously. As an organisation, while we condemn in no uncertain terms all those who advocate censorship, we would – as a free expression organisation – defend their right to express those views. What we do not and will never condone is the use of intimidation, force or violence to stifle the free expression of others.

As an anti-censorship organisation we think it is self-evident that no work should be censored for causing ‘offence’. But we also know that controversial art will inevitably cause controversy, including demands it be censored. Some of those who object to the work may protest. Some of those protests may turn violent. So we have also sought in much of our work on this issue not simply to condemn those who wish to censor, but also to examine what more arts organisations and institutions can do to ensure that controversial works are put on: Taking the Offensive – defending artistic freedom of expression in the UK.

We hope the debate generated by the cancellation of Exhibit B will reignite discussion on both the necessity of, and mechanisms for, staging controversial work.

This statement was posted on 26 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 2014 | Hungary, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (Pic © European People’s Party/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

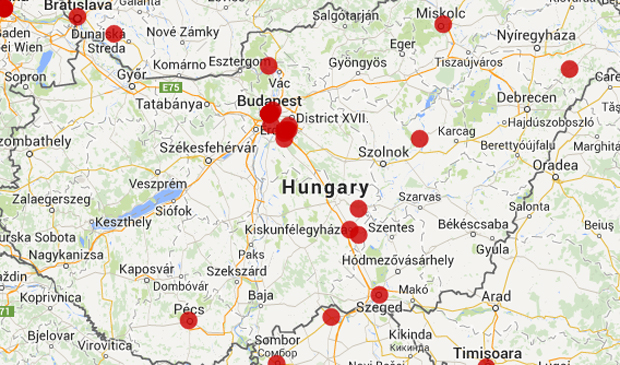

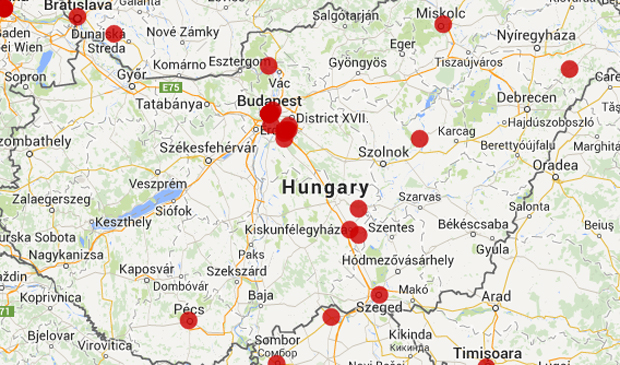

People “working together with foreign intelligence services” have been labelled “traitors” by Hungarian Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjen. The comment comes after news site index.hu published a series of investigations exposing how Ukrainians and Russians are using fraudulent techniques to get Hungarian citizenship, and then travelling in Europe with Hungarian passports. The incident follows a spate of cases of government censorship and intimidation over the past year, tracked by Index on Censorship‘s media freedom mapping project.

Earlier this month, two Hungarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) who received money from the Norwegian government under a 20-year-old deal to help strengthen civil society in the poorer parts of Europe, were raided by police officers from the National Bureau of Investigation.

Ökotárs and Demnet are just two NGOs who have recently come under attack in Hungary. A government “blacklist” of the 13 “most wanted” organisations was leaked in May. The total number of groups under investigation is at 58 and growing, and includes human rights and watchdog organisations like the Roma Press Centre, Labrisz Lesbian Association and Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU).

A campaign has been launched by a group of Hungarian volunteers through the site Blacklisted Hungarians, encouraging the international community to show their support for the case on social media by using the hashtag #ListMeToo to share content and media coverage.

In addition to this, rapper László Pityinger, known as Dopeman, is at the centre of an ongoing criminal investigation, after he kicked the detached head of a statue symbolising the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The rapper spoke at a demonstration arranged by political group Szolidaritás last October, during which the audience toppled and decapitated the statue.

He will be represented by HCLU. Dalma Dojcsák, the group’s political liberties program officer and freedom of speech expert, told Index they are trying to convince the police that Pityinger has not committed a crime.

“The police officer conducting the investigation implied that they think the same, but the prosecutors may force the case through the system until it gets to trial. We don’t know if it is going to happen,” Dojcsák said.

“In Hungary, prior, direct censorship is rare — it only happens in public service media that is ruled by the government. However, self-censorship is common among journalists, out of fear of legal procedures and losing state financed advertisement,” she added.

Deputy editor-in-chief fired from Nepszava daily

Two official bulletins appear in Kiskunfelegyhaza

28 journalists laid off by daily newspaper

Parliament speaker attempts to block interview from airing on Polish TV

Song with political reference cut from public broadcast

More reports from Hungary via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was posted on 26 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

“States must stop trying to define who is and isn’t a journalist. The media landscape has changed irreversibly,” said Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, as she opened the organisation’s Open Journalism event in Vienna on Friday, 19 Sept.

Journalism – wherever you draw its boundaries – has more voices than ever, but are all they all being properly recognised and safeguarded? This was one of the main problems addressed by the expert panel, which included Index on Censorship, alongside delegates from Azerbaijan, Serbia, Estonia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and many other OSCE member states.

Gill Phillips, the Guardian’s director of editorial legal services, spoke via pre-recorded video about difficulties in defining journalism and deciding who gets journalistic protection. She cited the Snowden scoop, which was led by Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer, and later embroiled his partner, David Miranda. Who gets the protection? Greenwald? Miranda? Lead staff reporter David Leigh? All three?

There was widespread condemnation of Russia’s new law, which compels bloggers with more than 3,000 views per day to be registered with the authorities. “[The bloggers] have certain privileges and obligations,” said Irina Levova, from the Russian Association of Electronic Communications, who repeatedly defended the law. “Online and offline rights are not the same,” she said, adding that some of those who deemed the law a mode of censorship have been revealed as “foreign agents”.

Another topic – raised repeatedly by various attendees – was Russian media’s growing influence over citizens in nearby countries. Begaim Usenova of the Media Policy Institute in Kyrgyzstan said: “The common view being spread from the Russian media is that the United States is starting world war three and only Putin can stop him.”

Yaman Akdeniz, a Turkish cyber-rights activist, shared news of Twitter accounts that remain blocked in his country, including some with over 500,000 followers. Igor Loskutov, a business director from Kazakhstan, looked back on the first 20 years of internet in his country and how authorities have gone from ignoring their first rudimentary websites to now wanting complete control.

The thorny issue of “public interest” was also discussed. Jose Alberto Azeredo Lopes, professor of International Law at the Catholic University of Porto, raised some smiles with his theory: “It’s like pornography. You can’t define it. But you know it when you see it.”

As the day-long discussions wrapped up, one delegate asked: if a blogger’s first-ever post goes viral, are they immediately subject to the same laws as the press? Especially in countries that now insist bloggers register.

The debate over the difference between journalists and bloggers went round in circles – as it always does – but the OSCE is hoping to be able to compile all the findings from its expert meetings into an online resource to move the discussion forward.

Azeredo Lopes concluded: “If you don’t distinguish freedom of expression from freedom of the press, you end up with no journalists, and that is the crisis that journalism faces today.”

Read our interview with Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media, in the autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, coming soon

This article was published on Friday September 26 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 2014 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Uncategorized

Rasul Jafarov in September 2013 (Photo: Melody Patry)

This is the appeal of Azerbaijani political prisoner, Rasul Jafarov. It was sent to Index on Censorship by his brother, Sanan Jafarov. Jafarov has now been detained for 54 days.

Article 157 of the Code of Criminal Procedure deals with the restrictive measure of arrest. Article 157.2 states that arrest as a restrictive measure may be chosen in the light of the requirements of Articles 155.1 – 155.3 of this Code. In other words, a restrictive measure, including the restrictive measure of arrest may be chosen when the grounds stipulated in the Articles 155.1 – 155.3 exist. These grounds are the following, and I present my arguments regarding the baselessness of the attribution of each ground to me and the fact that there was a ‘political order’:

- 1.1 – hiding from the prosecuting authority;

In connection with my activities as a human rights defender, I have regularly been in the spotlight of the local community and the media. At least once a week, I gave interviews to local media outlets in their offices. The interviews were explicitly related to the human rights situation in Azerbaijan. To talk about these issues one needs to constantly live in Azerbaijan. And I have always lived in Azerbaijan. Despite of making numerous trips in connection with my work, I always returned to the Homeland. This was the case on the eve of my arrest. I came back to Baku in late June after participating in the summer session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. From 29 June to 5 July I was on a visit to Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and from 6 to 11 of July on a visit to Kiev. The last visit is particularly important, because on July 7, while I was in Kiev, the Sabail District Court issued a decision to arrest my current bank accounts based on the request of the investigating authority, i.e. while stil in Kiev I already knew that the Prosecutor General’s Office conducts an investigation related to me. Nevertheless, I did not choose to hide from the investigating authority and returned to Baku on July 11. On July 16, I submitted a formal application to the Sabail District Court requesting a copy of the decision to arrest my bank accounts, in order to appeal that decision. On July 28, I left Baku for Tbilisi by train for a next working trip; in the morning of July 29, I was told at the Boyuk Kesik border crossing point that the Prosecutor General’s Office imposed a ban on my exit from the country on July 25. This ban is, as a rule, imposed on suspects and accused persons. However till then I had not been prosecuted as a suspect or accused. Yet, I not only did not think about hiding, but immediately returned to Baku after being taken off the train and informed the local media about this ban. After this information was disseminated in numerous media outlets, a member of the investigation team, an investigator by name Igbal Huseynov called me on July 30 and invited me as a witness to the Depatment for Investigation of Serious Crimes of the Prosecutor General’s Office on July 31, at 9.30. I did not hide from the investigation and was in the investigating authority at the specified time in order to answer the questions of the investigation. There, I gave evidence for 4 fours in the presence of two investigators, and answered all the questions that interested the investigating authority. After the questioning, a search was conducted in the apartment where I live for 2 hours with my own participation (the search order was made on July 25). Since the investigating authority found nothing as a result of the search, I told that I can voluntarily present the documents that the investigating authority needed. Thus, on July 31, August 1 and on the day of my arrest, i.e. August 2, voluntarily presented the financial and accounting documents of the human rights projects that we carried out during the period 2011-2014. On August 2, after presenting the last documents on the projects I was charged as the accused. Because I cooperated with the investigation, regularly complied with the summons of the investigating authorities and, above all, presented all the documents requested for normal conduction of the investigation, there remained no logical or any other point in my hiding from the investigation from that moment on. On the other hand, due to the ban imposed on my exit from the country, I could not hide from the investigation by leaving the country, even if I wanted.

- 1.2- obstructing the normal course of the investigation or court proceedings by illegally influencing parties to the criminal proceedings, hiding material significant to the prosecution or engaging in falsification;

Firstly, I should note that the scope of the persons involved in the criminal proceedings is unclear to me. The current criminal case was launced on 22 April 2014 and covers the activity of more than 20 NGOs and NGO representatives. In such a case, it is difficult to even imagine the possibility of how and which parties to the criminal proceedings were influenced during nearly 4 month until my arrest. If we answer the question “who were these people?” with assumptions, we can suppose these people to be the persons who rendered different services under the projects that we carried out. The projects that we carried out, the people involved in them, the documents that emerged as a result of projects and the outcomes have regularly been in the spotlight of local and a number of foreign media, and discussions have been opened around them. On the other hand, the identity of the persons involved in the projects, the jobs that they were engaged in and the amounts of funds they received in return for their work are indicated in the financial and accounting documents that I voluntarily presented to the investigating authority. I should underline that I present not the copies but the original documents to the investigating authority and relevant acts were drawn up. In such a case, there remains no point in inluencing the people involved in projects for any reason, because all original documents related to them have already been presented to the ivnestigating authority. This fact also proves the fact that it is impossible to falsify any document or material. Since on 3 consecutive days I voluntarily presented the documents requested by the investigation, the concealment of any document is out of the question, as we have no document to hide. The projects that we carried out were obvious, I gave additional information about each of the projects during my testimony on July 31, the investigating authority possesses bank statements about my bank accounts, I have presented all financial and accounting documents on the projects, thus I let the investigation know the exact scope of persons involved in the projects. This being the case, the hiding or falsying of which documents can one talk about? Or is there a need to influence the people, when their involvement in the projects is proved by their own signatures and the investigating authority already has these documents?

- 1.3 – committing a further act provided for in criminal law or creating a public threat.

The nature of the crimes with which I am charged is so that it is impossible to commit them again in the course of the current criminal proceedings; Because the projects have been stopped due to the criminal case, all my current bank accounts have been arrested by a court decision, the documents of all the previously implemented projects are in the possession of the investigating authority. This being the case, how can I re-commit the crimes with which I am charged? The crimes with which I am charged are not homicide, causing grievous bodily harm, hooliganism, drug possession, drug trafficking, rape or crimes resulting in serious consequences of these kinds, there do not exist grounds for prevention of their re-commital or a public threat.

- 1.4 failing to comply with a summons from the prosecuting authority, without good reason, or otherwise evading criminal responsibility or punishment;

As I noted above, the first time I was summoned by the investigation on July 30, and on July 31, at 9.30, I was at the investigating authority, I also complied with the August 1 and August 2 summons of the investigating authority in a timely manner, without any delay. As we can see, I not only did not avoid the summons of the investigating authority, to the contrary, I have consistently complied with them. After my July 31 evidence, the search in my apartment and the presentation of the documents to the investigation, I gave information about what had happened on my Facebook page, stating that my activity was transparent, that I had not committed any crime and that I would prove this to the investigation. I repeated my similar interviews in the interviews that I gave to the local media both on the same day and August 1.

- 1.5 preventing execution of a court judgment;

How might I have prevented the execution of a court judgment, when there exists no court judgment on this case or in relation to me. It has been set out in Article 155.2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure that in resolving the question of the necessity for a restrictive measure and which of them to apply to the specific suspect or accused, the preliminary investigator, investigator, prosecutor in charge of the procedural aspects of the investigation or court shall bear in mind:

155.2.1. the seriousness and nature of the offence with which the suspect or accused is charged and the conditions in which it was committed;

– Only one of the crimes with which I am charged, abuse of office, is considered a serious crime by its category, the other 2 crimes belong to the category of less serious crimes. In other words, if we summarize the crimes, among them, I am accused of committing only 2 less serious and 1 serious crimes. These charges filed against me cover my human rights activity that I have implemented for 3 years, i.e. I have established the non-governmental organization not to commit these crimes, but to implement human rights activity. And, I obtained the TIN (taxpayer identification number) in 2008 not to avoid payment of taxes or engage in illegal business activity, but to be registered as a taxpayer and pay the taxes. In other words, even if we suppose that the crimes have been committed, there are no proofs to claim the gravity of the circumstances of their committal, or to show that there was a specific intent or planning, or criminal intention in the action. As a result of the action that has been allegedly committed, no one has lost their life or suffered serious injuries, there has not been an obvious disrespect for a society, no one’s Constitutional rights or freedoms have been violated, and there is no concrete victim or complainant. The article of the Criminal Code that concerns tax evasion, one of the charges brought against me, itself provides for the exemption from criminal responsibility.

155.2.2 the personality, age, health and occupation of the suspect or accused and his family, financial and social positions, including whether he has dependents and a permanent residence;

– I have worked in civil society organizations since 2007, and have been author, implementer or participant of a number of projects that were useful for the society. I graduated from the university with good and excellent mars and got a master’s degree in law. In 2006-2007 I served in the army and was discharged with the rank of junior sergeant. I am considered the head of my family since 2004, as my father died in October of that year, and since then I play a key role in maintaining our family that consists of me, my mother and younger brother. I have a resident which is my property and the investigation knows this, there is no other address where I actually live, I do not have a citizenship of any other country or have no obligation to a foreign state. In 2010, I was the winner of the Asian Justice Makers Competition of the International Bridges to Justice organization, in 2013 I was a participant of the prestigious joint program of the American Jewish Committee and Fridrich Naumann Foundation called “Promoting Tolerance”, I closely participated in numerous meetings of the Council of Europe, the UN, the European Union, OSCE and other international organizations, and made speeches on the theme of human right at a number of events.

155.2.3 whether he has committed a previous offence, the previous choice of restrictive measure and other significant facts;

I have never been convicted before, no restrictive measure has ever chosen in respect of me, I have never been recognized as a suspect or accused in committal of a crime, even no administraive measure has ever been applied to me, and my name has not been mentioned in any criminal case. I complied with the summons of the investigating authority in a timely manner and cooperated with the investigation.

Conclusion

There was no ground to refuse choosing the measure of house arrested in respect of me as an alternative to the resitrictive measure of arrest. Along with the house arrest, the court could completely ban me from leaving my place of residence as an accompanying measure and additional restrictive measures stipulated in Article 163 of the Code of Criminal Procedure could be applied. We have presented reliable evidence proving this to all local courts. When our evidence are taken into account not seperately but as a whole, it becimes clear that there is no serious ground or necessity to apply restrictive measure of arrest to me. Thus, instead of arrest, the measure of house arrest, which is its alternative according to the legislation, could have been easily chosen in respect of me.

This article was posted on 25 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org