21 Jul 2015 | Art and the Law Reports, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports

Following a conversation at a What Next? meeting about the difficult situations cultural organisations can find themselves in when an action sparks controversy – for example, the presentation of a divisive piece of work, or a contentious sponsorship deal – What Next? has produced some practical guidance on ethics. The guidance responds to contributions from organisations across the UK to a What Next? survey on the subject of ethical and reputational challenges and is intended to help leaders meet such challenges with a greater sense of confidence.

“In working to sustain a thriving, vibrant and at times challenging cultural sector, there will be tricky decisions to make and the need to handle difference of opinion. In an increasingly complex world, the more that can be done to approach contention with courage and a zest for debate, the healthier our cultural and civic life. This guidance has been compiled to encourage bold, yet measured decision-making…”

Régis Cochefert, Director, Grants and Programmes, Paul Hamlyn Foundation

Many of the ideas in the document come from survey contributions and the content has been discussed and tested by an advisory group. It has been further informed by interviews across the sector and more widely. It does not attempt to offer definitive answers and every organisation will want to use it in different ways, taking and embedding what is useful to them.

Read the full report

20 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

Ann Morgan’s self-imposed challenge to read 196 books in a year taught her much about the world of literary censorship. Credit: Steve Lennon

“For as long as people have been telling stories other people have been trying to shut them up,” writes Ann Morgan in Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer. The book, published earlier this year, charts her bid to read a book from each of the world’s 196 independent states. In the 365-day challenge, she faced constant barriers, from trying to find literature in places with almost no publishing industry, such as the Marshall Islands, to tracking down the works that the authorities have tried to hide.

Morgan found herself getting a crash course in world censorship. Two of the exiled writers she profiled have stories featured in the summer 2015 edition of Index on Censorship magazine: Ak Welsapar from Turkmenistan and Hamid Ismailov from Uzbekistan.

It was a chance tweet that Morgan spotted about Welsapar’s poetry that first led her to the as-yet-unpublished translation of his novel, The Tale of Aypi. She was soon struck by his use of Aesopian language and allegory to communicate subversive or challenging ideas, a literary tactic that Welsapar revealed was by no means accidental. Morgan told Index, “Towards the end of the Soviet era there was a relative loophole in one of the censor’s guidance documents that said that if there was an element of doubt in what was meant, the writer had the benefit of the doubt. This was a grey area that was quite freeing for Ak.” However, when the country declared independence in 1991, he found himself more censored than ever before, his works were banned and he was forced to flee to Sweden.

Ismailov faced a similar plight. After working on a series of articles and projects that criticised the Uzbek regime, his books – and even any mention of his name – were forbidden. He fled the country and ended up in the UK, working for the BBC. Morgan said: “When [Ismailov] was growing up, he always thought there was something wrong with the literature he was reading. All the positives he’d been bombarded with in Soviet literature didn’t make sense. He was seeing this gap between his reality and the reality of what he was reading.”

But of the 196 countries Morgan explored on a literary level, North Korea was the one that intrigued her the most. Keen to discover what – if anything – is read within its fiercely guarded border, she contacted a spokesman for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (DPRK) Committee for Cultural Relations for Foreign Countries (run by Alejandro Cao De Benós, the first and only foreigner to be allowed to work for the government in North Korea) and, after much persistence, was eventually sent a manuscript of My Life and Faith, the memoir of jailed North Korean war correspondent Ri In Mo. Mo was imprisoned for 40 years in South Korea in 1950, after being arrested for fighting as a guerrilla during the Korean War. Although his autobiography is primarily used as propaganda, Morgan found his work far less two-dimensional than she had expected; it included thought-provoking passages on how Mo engaged with the South Korean media after his release and how his words were altered by journalists to make him sound “more North Korean”.

Morgan feels her interactions with the DPRK Committee and reading the corresponding work taught her much about our refusal in the west to engage with abhorrent ideas: “I got reactions from people saying you shouldn’t read anything from there [North Korea], but to me this was still censorship, it was quite sinister. How are you to have a dialogue and move forwards if you are banishing them from the realm of the human and not allowing for any common ground?”

So does she believe books such as hers can help bring people’s attention worldwide to the issues surrounding literary censorship and further publicise these semi-forgotten works? “Hopefully, the project has brought attention to the works of a number of those writers who I encountered, and the works of many other writers out there who I didn’t read directly. I hope it encourages readers generally to look further and I hope in the long run it will bring more opportunities for other writers.”

You can read short stories by Ak Welsapar and Hamid Ismailov in the summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Ann Morgan’s book, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer, was published in the UK by Harville Sacker in January 2015. Her blog is A year of reading the world.

17 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile

Index on Censorship magazine cover, May 2005

On behalf of all those who make a living from creativity, those whose job it is to analyse, to criticise and to satirise – authors, journalists, academics, actors, politicians and comedians – I oppose the government’s proposed law of Incitement of Religious Hatred. The government claims we need have no concerns about the legislation but as the arguments both for and against the measure have evolved, I have found these reassurances to lack any logic or conviction.

First, there is the government’s belief that the measure will promote racial tolerance. Now racial tolerance may sound a pretty inarguable notion. Unfortunately, what is very arguable is the definition of the term – the definition of a tolerant society. Is a tolerant society one in which you tolerate absurdities, iniquities and injustices simply because they are being perpetrated by or in the name of a religion? Or one where out of a desire not to rock the boat you pass no comment or criticism? Or is a tolerant society one where, in the name of freedom, the tolerance that is promoted is the tolerance of occasionally hearing things you don’t want to hear? Of reading things you don’t want to read? A society in which one is encouraged to question, to criticise and if necessary to ridicule any ideas and ideals, and where the holders of those ideals have an equal right to counter-criticise, to counter-argue and to make their case? That is my idea of a tolerant society: an open and vigorous one, not one that is closed and stifled in some contrived notion of correctness.

I question, also, the ease with which the existing race hatred legislation is going to be extended simply by the scoring out of the word “racial hatred” and the insertion of “racial or religious hatred” as if race and religion are very similar ideas and we can bundle them together in one big lump. It seems clear to me and to most people that race and religion are fundamentally different concepts, requiring completely different treatment under the law. To criticise people for their race is manifestly irrational but to criticise their religion, that is a right. That is a freedom. The freedom to criticise ideas – any ideas – even if they are sincerely held beliefs, is one of the fundamental freedoms of society. A law that attempts to say you can criticise or ridicule ideas as long as they are not religious ideas is a very peculiar law indeed. It promotes the idea that there should be a right not to be offended. Yet in my view, the right to offend is far more important than any right not to be offended simply because one represents openness, the other oppression.

Third, I question the inarguable nature of the phrase “religious hatred” afforded by the use of the highly emotive word “hatred”. So I thought I would modify the name of the proposed measure by changing the terminology while retaining the meaning. The dictionary definition of the word “hatred” is “intense dislike”. Incitement of Religious Intense Dislike. Isn’t it strange how that small change makes it seem a much less desirable or necessary measure? I then found myself asking a strange question. What is wrong with encouraging intense dislike of a religion? Why shouldn’t you do so if the beliefs of that religion or the activities perpetrated in its name deserve to be intensely disliked? What if the teaching or beliefs of the religion are so outmoded, hypocritical and hateful that not expressing criticism of them would be perverse? The government claims that one would be allowed to say what one liked about beliefs because the measure is not intended to defend beliefs but believers. But I don’t see how you can distinguish between them. Beliefs are only invested with life and meaning by believers. If you attack beliefs, you are automatically attacking those who believe the beliefs. You wouldn’t need to criticise the beliefs if no one believed them.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

I also take issue with the government’s consultation process. After the initial failure to get the law passed in 2001, it engaged in a consultation process involving a House of Lords Select Committee and, I believe, another forum in which it was discussed, to arrive at a new version of the measure that was launched last autumn. What I find extraordinary is that the government is so wedded to the notion that nobody other than the most rabid fascists could possibly fall foul of this legislation that the consultation process didn’t include anyone from the creative community. Many organisations were consulted in the drafting of this legislation: religious organisations, civil liberties groups, law enforcement people; but not one writer, not one journalist, not one academic, not one television producer, theatrical producer; no actor, no comedian; basically nobody whose work might be affected by it. How weird this denial of those concerns, when the incident that most inspired those who have been seeking the introduction of this legislation was the publication of a book. And the most vociferous religious protests we have seen in Britain in the past few months have been against a play and a televised opera. Again, the government will say that these creative works are not the intended targets of this legislation but that raises two issues: first, many religious organisations think they are precisely the target and look forward to wielding their influence to bring prosecutions. If their ambitions are thwarted, there is a high risk of a violent reaction; second, the government is unable to say that creative endeavours could not possibly be targets. And the reason ministers can’t give that degree of reassurance is because creative endeavours clearly could be. Comedy could. Newspaper articles could. Theatrical plays could. The legislation is very simple, very clear and very broad.

The government is relying entirely on the wisdom of the attorney general to protect people like me. It is this discretionary nature of the legislation that is arguably the most disturbing thing about it. It allows the government to rubbish the concerns of the creative community without offering any concrete reassurances other than that the attorney general will look after you. What kind of reassurance is that? The attorney general is not an independent adjudicator. He is an instrument of government: what is politically expedient will be his guide. As the 9/11 attacks on the United States showed, the political agenda in any country can change in a matter of hours. Who’s to say what his priorities are going to be in five days’ time, or five hours’ time, or five years’ time? The government’s belief that legislation on religious hatred will work just as that on racial hatred does is optimistic in the extreme. The pressures in relation to religious hatred are going to be on a completely different scale from that for race: the spread of fundamentalism across a whole range of religions is going to make the issue politically far more highly charged.

And even if I had faith that the attorney general would bail me out in the end, what would I have to go through first? I don’t particularly want to discover that my comedy revue has not, after all, fallen foul of the legislation sitting in an interview room in Paddington Green police station. I would like to know that I could not possibly be put in that situation because of my criticism or ridicule of religious ideas and, by implication, those who follow those ideas. And we now know that even the attorney general’s judgments can be subjected to judicial review. Where would it end?

However, we have to address the issues that have driven the government to their current position. We have to sympathise and empathise with the most conspicuous promoters of this legislation, British Muslims. I appreciate that this measure is an attempt to provide comfort and protection to them but unfortunately it is a wholly inappropriate response far more likely to promote tension between communities than tolerance. The government could have worded the document to tackle a specific issue but chose not to; as a result, those caught in the crossfire are reluctantly going to have to fight to defend intellectual curiosity, the right to criticise ideas, whatever form they take, and the right to ridicule the ridiculous, in whatever context that lies. These ramifications are being denied by the government because it is politically expedient for them to do so, but I personally have been reassured by nothing I have seen, heard or read.

I don’t doubt the sincerity of those who are seeking this legislation but I do question the government’s enthusiasm for it so close to a general election, an enthusiasm that must be rooted in its belief that this measure could help its cause in some marginal constituencies with large religious populations, many of whom are critical of the government’s prosecution of the war in Iraq. It seems a shame we have to be robbed permanently of one of the pillars of freedom of expression because it’s needed temporarily to shore up a wobbling political edifice elsewhere.

Rowan Atkinson is a foremost British comedian and actor. This is the speech he gave in the Moses Room at the House of Lords on 25 January 2005

This article is from the spring 2005 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

This article is from the spring 2005 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

16 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

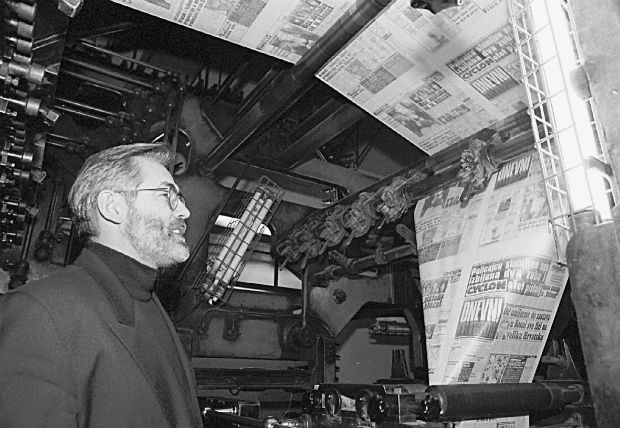

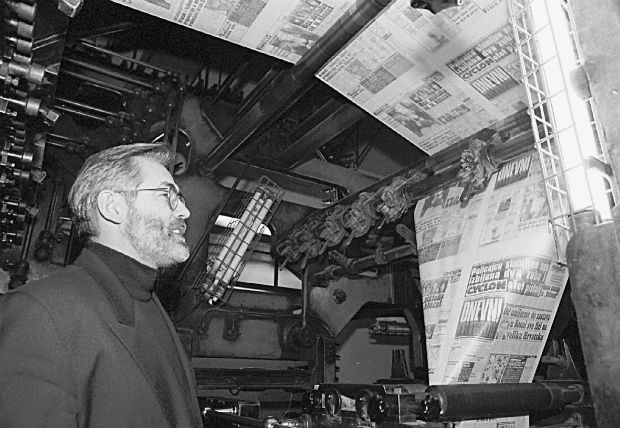

Journalist Slavko Curuvija, murdered in Belgrade in 1999 (Photo: Predrag Mitic)

As NATO bombs were falling on the Serbian capital Belgrade on 11 April 1999 , a man was being executed on a side street in the centre of the city. The victim was later identified as Slavko Curuvija, a prominent Serbian anti-regime journalist. A post mortem found that Curuvija had been shot in the back 17 times. Five days earlier the state-run daily Politika Ekspres had published an article calling Curuvija a traitor and a NATO supporter.

Fast forward to 1 June 2015: the trial of four former security officers begins before a special court in Belgrade. It took 16 years for anyone to stand trial over what had become a notorious case of intimidation of journalists in Serbia.

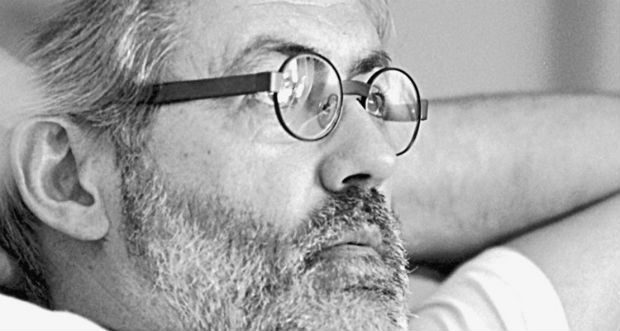

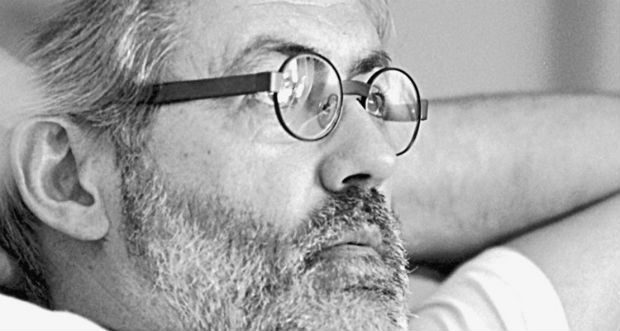

Much of the credit for pursuing a cause by many considered lost can go to veteran journalist Veran Matic, the editor-in-chief of media group B92.

Several Serbian governments had shown no signs that they were willing to solve Curuvija’s case; the same goes for many other war-time murders. For years, Matic and his fellow journalists would mark the anniversary of Curuvija’s death by laying flowers at Svetogorska Street, where he lived and died, and by raising awareness in the media and with the government. It was not enough.

In 2013, Matic was fed up with waiting for answers about the murders of his colleagues. He proposed to form a special body to investigate the killings of Curuvija and two other journalists. Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic — then deputy prime minister — gave Matic permission to form the Commission for Investigating Killings of Journalists in Serbia. It was an unexpected move. As Curuvija was being executed on a Belgrade side street, Vucic was minister of information in President Slobodan Milosevic’s government.

“Some criticised the establishment of the commission for giving an opportunity to Vucic to clear his past,” says Matic, referring to the unease many journalists felt towards Vucic, who was highly critical towards independent media during the nineties.

“Marking every year the anniversary of the killing, visiting the place of assault, criticising the state again and again for failing to resolve those crimes became very humiliating for me,” Matic said. “In this way, I have been given another instrument through which I could do something in practice.”

It was clear that Matic needed the government’s cooperation if he wanted the murders to be solved. “I wanted to get hold of every single document and, in order to do this, we needed a commission that would be supported by the government,” he said. But Matic managed to ensure the body was made up of three representatives of the independent media, three members of the ministry of internal affairs and three representatives of the security information agency. With Matic himself serving as the commission’s chairman, journalists will always be in the majority.

Progress and challenges

(Photo: Predrag Mitic)

The commission is focusing on three big murder cases from the recent past. The work around Curuvija’s case has been the most successful until now, with four people charged. Trials for former Chief of State Security Rade Markovic and the two ex-secret service officers Ratko Romic and Milan Radonjic began 1 June. The fourth accused is Miroslav Kurak, also a former state security member and the man who is believed to have pulled the trigger on Curuvija. He is being tried in absentia, as he is still at large, an Interpol warrant issued for his arrest. There are clues that Kurak is living in Central or South Africa where he owns a hunting safari agency.

The Dada Vujasinovic case is perhaps the most difficult, as the murder took place over two decades ago. Vujasinovic was a reporter for the news magazine Duga and wrote about Zeljko Raznatovic, also known as Arkan. She was found dead in her apartment in 1994. The police ruled it a suicide, but most evidence disputes this. When the commission started working on the case, there were doubts about the forensic research done in Serbia at the time. “I decided that the first step would be to seek expertise outside of the country, as the trust in domestic institutions had been compromised,” said Matic. “We asked the Dutch National Forensic Institute based in The Hague, who offered to perform the forensic examinations for 35,000 euro. We are now raising funds for this, given that the prosecutor’s office has no budget for these services.”

The third case is that of Milan Pantic, who was murdered in June 2001 while entering his apartment building in the central Serbian town of Jagodina. Attackers broke his neck, and was also struck on the head with a sharp object. Pantic worked for the newspaper Vecernje Novosti, where he reported on criminal affairs and corruption in local companies. Prior to the killing, he had received numerous telephone threats in response to articles he had written. It’s not an easy task to investigate. “We know that one of the suspects is living in Germany under a different name,” explained Matic. “But we didn’t get permission to conduct an interview with him.”

The commission is also looking into the deaths of 16 media staffers from RTS — Serbia’s state broadcaster — who were killed during a NATO airstrike targeting its headquarters in 1999. “This is a very complex issue,” said Matic. “The executioner is certainly a pilot of one of the NATO member countries. The people who decided to put a media company on the list of war targets should face trial, as well as those who issued the order to launch missiles and kill the media workers. And also the people responsible in Serbia, who knew the building would be bombed and did not evacuate it.” NATO is refusing to cooperate in this case.

Unique commission

It is of great importance, Matic believes, that these cold cases will be solved. “Unpunished crimes, especially this committed by state institutions, only call for new violence, threats and endangerment of the safety of journalists. It leaves deep scars in the lives of journalists in this country and it contributes to censorship and fear.”

A commission like this is unique in the world; a government body controlled by independent media representatives. And its first success, the arrests in the Curuvija murder case, was surprising to many who’d lost faith in the justice system in Serbia. “This commission was not established by politicians. On the contrary, they accepted all my requests and ideas,” said Matic. “This is quite an atypical commission that works on making results, and none of its members have any political or other motives, but solely finding the killers and masterminds that hide behind the killings, and bringing them to justice.”

Jailing the head of Serbia’s secret service during the nineties, a dark period for both the country and its internal security apparatus, has come with a high price. Matic now lives under 24/7 police protection and he can’t travel anywhere without a police escort. “Some names have again been brought to light, along with their disgraceful role [in the killings]. Some are threatened with arrest, while some of them have been arrested already,” he said of the ongoing investigation.

Matic receives threats often, mostly via email, some of them to his life. But he has gotten used to having police officers in front of his door at all times because, he said, the truth is worth the compromise.

“This is the price we have to pay in order to resolve those crimes,” he said. “It will contribute to the catharsis of our society.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

An earlier version of this article stated that Aleksandar Vucic was interior minister when the commission was set up. This has been corrected.

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org