21 Sep 2016 | Magazine, mobile, News and features, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras, Youth Board

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, The Unnamed: Does anonymity need to be defended?, Index’s contributing editor for Turkey, Kaya Genç, explores anonymous artists in Turkey. In the piece the artists discuss how vital anonymity is in allowing them to complete their more controversial work. The Index on Censorship youth advisory board have taken inspiration from this piece for their latest task, in which they investigate anonymous art around the world.

Keizer by Constantin Eckner

Ants feature in Keizer’s work to sybolise “the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism”. Image: Keizer

Prior to the January 25 Revolution political street art was anything but common in Egypt, yet it has proliferated in public spaces in the aftermath of the revolution. One of the most productive street artists in Cairo is Keizer, who has gained popularity and notoriety in recent years. Like Banksy and other street artists, he uses the well-known stencil technique to empower his fellow countrymen, and people in general, with his thought-provoking work. He likens people to ants, which are featured in most of his graffiti. Keizer explains on his Facebook account that the ant “symbolises the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism. They are the working class, the common people, the colony that struggles and sacrifices blindly for the queen ant and her monarchy.”

Asked about the reason for protecting his identity, Keizer said: “I am very concerned over my safety and the repercussions of street art which I’ve already had a taste of, especially with this current regime. Including death threats,

Egyptian street artist Keizer has gained popularity in recent years. Image: Keizer

my twitter account was hacked twice. In the past five years of working on the street I’ve been caught once. I came out of it with a few bumps and bruises, nothing major. I consider myself lucky that I came out one day later.

“You can imagine that being caught here is very different than being caught in Europe. There is no proper procedure and that makes you a victim of the person handling you, and the uncertainty of what comes next. Graffiti is a grey area here, they don’t have any definition or classification for it in the books, so they make it up as they go along, taking you for the fear ride. It’s all under vandalism, so they can make it look small or escalate it to exaggerated levels. For instance, you can be dubbed as a political traitor; it can be considered racketeering; they can glue your name to any political movement unpopular with the people…etc.”

Tall walls, low profiles: Icy and Sot by Layli Foroudi

Icy and Sot describe themselves as stencil artists from Tabriz, Iran. As for their identities, they reveal only that they are brothers, born in 1985 and 1991. Their work is created under pseudonyms in countries around the world, including Iran, USA, Germany, Norway, and China, on legal and illegal walls as well as in galleries.

The anonymous duo, who paint on themes like human rights, censorship, and justice, say that charges against artists in Iran make going public risky.

“Pseudonyms help us to keep a low profile,” the brothers explained in an interview with ArtInfo, “Being arrested in Iran is completely different, because they charge you with crimes that you have not even committed, like Satanism or political crimes.”

Their work often uses striking human faces in black and white to make statements about politics and the environment, to call for peace, and to direct messages at the government of Iran. In 2015, Icy and Sot used their art to protest for freedom of expression in Iran, prompted by the arrest and 18-month imprisonment of Atena Farghadani, an Iranian artist who was detained for publishing a cartoon that satirised the Iranian government as animals. In solidarity, they stenciled a tribute piece depicting Farghadani with a backdrop of protesters on a wall in Brooklyn.

Maeztro Urbano’s fight to change a criminal image by Ian Morse.

In the most recent data, Honduras has the highest homicide rate in the world, with 84 intentional homicides per 100,000 people in 2013. The prominence of drug trafficking and ubiquity of poverty does not improve its reputation.

To some Hondurans, their country’s international image has done nothing but hurt citizen’s attempts to improve daily life in the country’s bustling cities and lively cultural centers. Maeztro Urbano and his friends became the face of an urban street art project to disrupt the atmosphere of crime and reveal another side of the country outside of the headlines.

His projects range from adjusting street signs promoting gender equality to vandalising billboards with corrupt politicians, to wall graffiti showing the effect of violence on children. Working his day shifts in the advertising industry, Maeztro Urbano said he wants to contribute more to his country than proliferating consumerism.

“Change should start within society. With each individual,” El Maestro – as he is also called – told The Creators Project. “To have respect for the lives of others, to respect the right to sexual diversity, to a better education.”

“If we don’t change that as a society and as individuals, we will never be able to change as a country.”

Assailants in Honduras have not been very hospitable to those reporting on crime or those wishing to express their identity. Faced with police harassment and shootings from unknown attackers, Maeztro Urbano chooses to wear a mask while he works to spread messages of hope around the country.

Bleeps.gr: Over a decade of political artivism in Athens by Anna Gumbau.

Bleeps.gr is one of Greece’s most prominent street artists, having painted murals on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. Image: Bleeps.gr

“I have been radically oriented to the political discourse, utilising the public sphere, and I am not afraid or discouraged”, Bleeps.gr, one of the most prominent Greek street artists, told Index.

Bleep.gr has been designing murals, that are mostly critical of the austerity policies imposed to Greece, on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. The Greek social turmoil has had a strong influence on his artwork, not only in his scenes, but even in his methods. “I buy very cheap materials and can’t afford those impressive equipment to create a mural”, he said in an interview with Street Art Europe.

Bleeps.gr chooses to use a pseudonym as an attempt to challenge “the institutionalised perception of the identity”, he told Index. While he is not afraid of the state authorities, he points at art institutions, such as galleries, exhibitions and festivals, who reject and exclude his art. “Most of the censorship I have received has come from other artists, especially the ones related to systemic initiatives, who in the past years have removed all of my works from the city center” he said. Greek political street artists often suffer from the exclusion of art galleries and exhibitors; in the summer of 2013, the CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS? street art festival in Athens, which celebrates the value of street art in the current political happenings, invited 20 artists from different European countries but failed to invite any Greek artists.

Nevertheless, Bleeps.gr stresses the fact that the internet “has provided a virtual field of allocation”, and most of the political street art discourse happens there.

Bleeps.gr highlights the mechanisms of such institutions to “absorb street artists” and make them become part of the art “business”, adding: “the majority of them nowadays serve gentrification policies and turn policies and turn political art into a spectacle for tourist pleasure”.

King of Spades by Sophia Smith-Galer.

When it comes to anonymous artists, the art tends to speak far louder than any speculation into the artist themselves. This anonymous artist in Lebanon is no Arab Banksy that lurks tantalisingly close to the limelight; this artist could quite literally be anyone, and the lack of anybody claiming the piece as their own is revelatory of the grave reality of artists in developing countries that test the patience of despots and tyrants.

Despite its tired and no longer relevant label “Paris of the Middle East”, even the dazzlingly artistic city of Beirut, Lebanon, can’t quite get away with hanging something like this banner, depicting the late Saudi Arabian monarch King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz as a brutal King of Spades. Shortly after its creation in 2013, the Lebanese state prosecutor ordered an investigation to reveal the source of these posters after complaints from Saudi Ambassador Ali Awad Asiri.

It seems that nobody got caught, and nor do I particularly want to dwell on what would have happened to the artist if they had. But in the Middle East, such a daring artistic expression must be forbidden fruit in a region of gagged political artistry; demonstrated no better than in this mysterious artist who gambled with the assumed impunity of that gentleman with the bloodied scimitar.

Dede Bandaid by Shruti Venkatraman.

One of Dede Bandaid’s most well known works, a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014. Image: Dede Bandaid / Wikicommons

Dede Bandaid is an anonymous Israeli artist who has added colour to Tel Aviv’s streets with thought provoking and politically relevant street art. His artistic career began in 2000 during his compulsory military service, and most of his earlier pieces demonstrated a clear anti-establishment sentiment. His more recent works, following the end of his stint in the military, aim to communicate social and political messages. One of his most well known works is a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014.

Dede enjoys using public spaces as a canvas as this approach allows freer and more controversial expression, while also being accessible to and viewable by a larger audience especially when the street art is photographed and its images are circulated online. He also makes use of traditional symbols of peace, like the white dove, and frequently incorporates Band-Aids that represent healing and remedy in his artwork, with “Bandaid” being the pseudonym he signs on all his pieces. Over time, Dede’s style has evolved from stencilling to free-hand painting and collage and he interestingly also exhibits certain pieces in galleries across the world.

Cabbage Walker in Kashmir by Niharika Pandit.

A pheran-clad man walks around with a cabbage on a leash in the neighbourhoods of Srinagar, Kashmir. This performance act that he presents is inspired by Chinese artist Han Bing’s “Walking the Cabbage” social intervention work. While Bing chose to walk the cabbage to reflect on the changing values in the Chinese society, where once cabbage was a subsistence food product but is now only embraced by the poor, in Kashmir, this anonymous artist aims to normalise the cabbage walking to show the absurdity of militarisation in the region. Both the performances employ cabbage as an element of satire to expose the irony inherent in what how elitism and militarisation come to be normalised in societies across the world.

The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker writes on his blog, “I as a Kashmiri am willing to recognise walking the cabbage as part of the Kashmiri landscape but I will never accept the check posts, the bunkers, the army camps, the torture centers, the barbed wire, the curfews, the arrests, the toxic environment of conflict and war, as part of the same.”

This performance artist chooses to remain anonymous as it helps in focusing on the message and not the messenger. The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker says that he represents all Kashmiri lives under militarisation thereby revealing the artist’s identity becomes unimportant here.

Cracked pavements in Budapest by Fruzsina Katona.

Anonymous volunteers have joined the satirial political party the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) to paint cracked pavement on the streets of Budapest. Image: Fruzsina Katona

Anonymity does not necessarily mean that one is trying to hide his or her identity. Sometimes the identity of the person is utterly irrelevant. In Budapest, several anonymous volunteers are painting the streets of the city.

The pavement on the streets of the Hungarian capital are falling apart, ruining the image of the city and endangering those who walk on it. Authorities are known to do very little to fix the problem, but something had to be done. Hungary’s satiric political party, the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) called for action and its artsy, anonymous volunteers started colouring the cracked pavement pieces resulting in dozens of cheerful spots across the city.

Unfortunately, there are some who find quarrels in a straw, and the police were called on the ad-hoc artists while they were peacefully decorating the pavement in a touristic neighbourhood. Now the volunteers are being prosecuted with vandalism.

But we still do not know their identity or how many of them are out decorating. All we know is that now we look at colourful patches of pavements while running our errands, instead of the sad and ugly cracked pavements.

20 Sep 2016 | Events, mobile

Join Index on Censorship and English PEN for a vigil outside the Turkish embassy in support of Ayşe Çelik and others currently persecuted for speaking out in Turkey. This vigil is part of a global campaign launched by the Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey.

Çelik, a teacher, will stand trial beginning on Friday, accused of “promoting terrorist organisation propaganda” after she called in to a popular television entertainment show to plead for more media coverage of abuse and killings of civilians in Diyarbakir, south-east Turkey.

Thirty-one people who co-signed Çelik’s statement will also be tried alongside her. They all face more than seven years in prison if found guilty.

Index on Censorship stands with Ayşe Çelik and will not ignore this breach of her basic right to freedom of expression. We denounce the current crackdown undertaken by authorities in Turkey and call for the immediate and unconditional release of imprisoned writers Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Asli Erdogan and Necmiye Alpay.

We will be outside the Turkish embassy from 2pm to 3pm.

Here is the full statement that landed Çelik in court:

Are you aware of what’s going on in Southeast Turkey? Unborn children, mothers, people are being killed here. As a performer, as a human being you should not remain silent to what’s happening. You should say stop. I want to say one more thing. There are miserable people who are glad to hear that children are dying. We, more correctly I, cannot say anything to these people, but shame on you. I’m sorry I want to say one more thing. I’m a teacher and I’m asking all teachers (who fled the area): How will they ever go back to these places? How will they look at those innocent children’s faces and into their eyes? I can’t speak really. The things happening here are reflected so differently on TV screens or on the media. Don’t remain silent. As a human being, have a sensitive approach. See, hear and lend a hand to us. It’s a pity, don’t let those people, those children die; don’t let the mothers cry anymore. I can’t even speak over the sounds of the bombs and bullets. People are struggling with starvation and thirst, babies and children too. Don’t remain silent.

When: Friday 23 September 2pm

Where: 43 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PA (Map)

19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

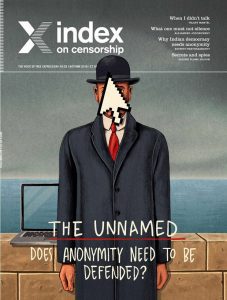

Autumn 2016 magazine cover

Anonymity is out of fashion. There are plenty of critics who want it banned on social media. It’s part of a harmful armoury of abuse, they argue.

Certainly, social media use seems to be doing its best to feed this argument. There are those anonymous trolls who sent vile verbal attacks to writers such as US author Lindy West. She was confronted by someone who actually set up a fake Twitter account under the name of her dead father.

Anonymity has been used in other ways by the unscrupulous. Earlier this year, a free messaging app called Kik was the method two young men used to get in touch with a 13-year-old girl, with whom they made friends online and then invited her to meet. They were later charged with her murder. Participants who use Kik to chat do not have to register their real names or phone numbers, according to a report on the court case in the New York Times, which cited other current cases linked to Kik activity including using it to send child pornography.

So why do we need anonymity? Why does it matter? Why don’t we just ban it or make it illegal if it can be used for all these harmful purposes? Anonymity is an integral part of our freedom of expression. For many people it is a valuable way of allowing them to speak. It protects from danger, and it allows those who wouldn’t be able to speak or write to get the words out.

“If anonymity wasn’t allowed any more, then I wouldn’t use social media,” a 14-year-old told me over the kitchen table a few weeks ago. He uses forums on the website Reddit to have debates about politics and religion, where he wants to express his view “without people underestimating my age”.

Anonymity to this teenager is something that works for him; lets him operate in discussions where he wants to try out his arguments and gain experience in debates. Anonymity means no one judges who he is or his right to join in.

For others, using a fake or pen name adds a different layer of security. Writers for this magazine worry about their personal safety and sometimes ask for their names not to be carried on articles they write. In the current issue, an activist who works helping people find ways around China’s great internet wall is one of our authors who can’t divulge his name because of the work he does.

Throughout history journalists have worked with sources who want to see important information exposed, but do not want their own identity to be made public. Look at the Watergate exposé or the Boston Globe investigation into child sex abuse by priests. Anonymous sources can provide essential evidence that helps keep an investigation on track.

That right, to keep sources private, has been the source of court actions against journalists through the years. And those who choose to work with journalists, often rely on that long held practice.

Pen names, pseudonyms, fake identities have all have been used for admirable and understandable purposes over the centuries: to protect someone’s life; to blow a whistle on a crime; for a woman to get published at a period when only men did so, and on and on. Those who fought for democracy, the right to protest and other rights, often had operate under the wire, out of the searching eyes of those who sought to stop them. Thomas Paine, who wrote the famous pamphlet Common Sense “Addressed to Inhabitants of America”, advocating the independence of the 13 states from Britain, first published his words in 1776 anonymously.

From the early days of Index on Censorship, when writing was being smuggled across borders and out of authoritarian countries, the need for anonymity was paramount.

Over the years it has been argued that anonymity is a vital component in the machinery of freedom of expression. In the USA, the American Civil Liberties Union argues that anonymity is a First Amendment right, given in the Constitution. As far back as 1996, a legal case was taken in Georgia, USA, to restrict users from using pseudonyms on the internet.

Today, in India, the world’s largest democracy, there are discussions about making anonymity unlawful. Our article by lawyer and writer Suhrith Parthasarathy considers why if minister Maneka Gandhi does go ahead with plans to remove anonymity on Twitter it could have ramifications for other forms of writing. As Anja Kovacs of the Internet Democracy Project told Index, “democracy virtually demands anonymity. It’s crucial for both the protection of privacy rights and the right to freedom of expression”.

We must make sure that new systems aimed at tackling crime do not relinquish our right to anonymity. Anonymity matters, let’s remember it has a role to play.

Order your full-colour print copy of our anonymity magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The full contents of the magazine can be read here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011400799″][vc_custom_heading text=”Going local” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011400799|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

If the US’s internet freedom agenda is going to be effective, it must start by supporting grassroots activists on their own terms, says Ivan Sigal.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89073″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013512242″][vc_custom_heading text=”On the ground” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013512242|||”][vc_column_text]December 2013

Attacked by the government and the populist press alike, political bloggers and Twitter users in Greece struggle to make their voices heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89161″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011409641″][vc_custom_heading text=”Meet the trolls” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011409641|||”][vc_column_text]June 2011

Whitney Phillips reports on a loose community of anarchic and anonymous people is testing the limits of free speech on the internet.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2016 Index on Censorship magazine explores topics on anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world.

With: Valerie Plame Wilson, Ananya Azad, Hilary Mantel[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80570″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/the-unnamed/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]