[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Using fiction and stories to influence society is nothing new, but facts are needed to drive the most powerful campaigns, argues Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2018 Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

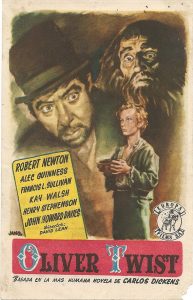

Poster for the 1948 film adaptation of Charles Dickens Oliver Twist (Photo: Ethan Edwards/Flickr)

My friend’s dad just doesn’t believe that UK unemployment levels are incredibly low. He thinks the country is in a terrible state. So when I sit down and say unemployment in 2018 is at 4.2%, the joint lowest level since 1971, he doesn’t really argue. Because he doesn’t believe it.

Well, I say, these are the official figures from the Office for National Statistics. His response is: “Hmm.” Clearly my interjection hasn’t made any difference at all.

He raises an eyebrow to signify, “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”.

This figure, and the picture it sketches, doesn’t chime with his national view, which is that things are very, very bad. And it doesn’t chime with the picture sketched in the newspaper that he reads every day, which is that things are very, very bad.

So, consequently, whatever facts or figures or sources you might throw at him to prove otherwise, nothing makes an impression on him. He believes that the world is the way he believes it is. No question.

Like many people, my friend’s dad reads news stories that reflect what he believes already, and discards stories or announcements that don’t.

And in itself, that is nothing new. For decades people have trusted their neighbours more than people far away. They have read a newspaper that echoed their political persuasion, and sometimes they have felt that the society they lived in was worse than it used to be, even when all the indicators showed their lives had improved.

Often humans believe in ideas by instinct, not because they are presented with a graph. In 2005, Drew Westen, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Emory University, in Atlanta, USA, published The Political Brain. In it, he argued that the public often made decisions to support political parties based on emotions, not data or fact.

The book struck home with activists, who tried to utilise Westen’s thinking by changing the way they campaigned. Politicians had to capture the public’s hearts and minds, Westen said. He talked about the role of emotion in deciding the fate of a nation and gave examples. When US President Lyndon Johnson proposed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outlawed racial discrimination at the US ballot box, he used personal stories to make his points stronger, said Westen, adding that this was a powerful tool. In doing so, Westen was ahead of his time in acknowledging just how strongly humans value emotion, and how an emotional action can be driven by feeling and desire rather than the latest data from a governmental body.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Westen used his thesis to show why he felt US Democratic candidates Al Gore and Michael Dukakis had failed to get elected, and why George W Bush had. Bush, he felt, was in touch with his emotional side while Dukakis and Gore tended to turn to dry data and detail.

That argument about how emotional beliefs or gut feelings are being used to influence important decisions has raced up the agenda since President Donald Trump arrived in the White House, the UK voted for Brexit and with the use of emotionally driven political campaigns to shift public opinion in Hungary and Poland.

Suddenly this question of why people were responding to appeals to emotion and dismissing facts was the debate of the moment. In many ways this is nothing new but the methods of receiving ideas and information are different. Now we have Facebook and Instagram posts, and zillions of tweets to spin and challenge.

One part of it, the articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist, or Victorian writer Charles Kingsley’s story The Water Babies. Kingsley’s tale of child chimney sweeps helped to introduce the 1864 Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act, which improved the lives of those children significantly.

Fictional stories, like these, have always played a part in changing attitudes, but also draw on reality. Dickens and Kingsley were outraged by the living and working conditions they saw, so they chose to try to effect change by using fictional stories to engage a wider public. And personal stories are also used to illuminate wider factual trends. For years journalists have used a case study as an explainer for something more detailed.

Facts and figures undoubtedly must have a role. Even when it appears there is public resistance to acceptance of data, something such as the fact that if you wear a seatbelt when driving a car you will have a better chance of surviving an accident becomes an accepted truth over time. Public information and published statistics clearly play a part in that shift.

That’s why it is so vital that public access to information is protected and that incorrect facts are challenged. This month, 28 September is the international day for universal access to information, something that concentrates the mind when you look at places where access is limited, or where government data is skewed to such a level that it becomes almost pointless.

Journalists reporting in countries including Belarus and the Maldives tell us their quest for trustworthy sources of national information are almost impossible to find as their governments refuse to respond to media requests or release untrue information. Officials also use smear tactics to undermine reporters’ reputations, so their accurate journalism is not believed. Governments know that by keeping information from the media they hamper a journalist’s ability to report, and in doing so may keep a scandal from the public. If facts and data didn’t make a difference, those governments would have no reason to restrict access.

Freedom to access information goes hand in hand with freedom of the media and academic freedom in creating an open democratic society. But at Index, we constantly see signs of governments, and others, trying to prevent both access to facts and to suppress writing about inconvenient truths.

In this issue of the magazine, we explore all aspects of this struggle to balance facts and emotion, the quest to find the truth, how we are influenced, and why arguments, debates and discussions are so vital.

There’s lots to read, from Julian Baggini’s piece (p24) on why people might fear a disagreement to tips on how to have an argument from Timandra Harkness (p31). Then there’s Martin Rowson’s Stripsearch cartoon (p26). Our interview with British TV presenter Evan Davis discusses whether lies tend to be found out over time, and the likelihood that people will select facts that support their political position.

What’s it like to be a scientist in the USA right now? Michael Halpern from the Union of Concerned Scientists in the USA says scientists are suddenly getting active to push back against a political climate attempting to take the factfile away from important government departments.

Almost every day a new story pops up outlining another attack on media freedom in Tanzania, and in this issue Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein reveals how bloggers are being priced out of the country (p70) as the government uses new fees to close down independent voices.

Then there’s Nobel prize winner Herta Müller on her experiences of censorship as a writer living in communist Romania (p67), and Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s poems written in prison (p86).

And finally, look out for our Banned Books Week events coming up at the end of September – find out more on the website. You’ll also find the magazine podcast, with interviews with broadcaster Claire Fox and Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze, on Soundcloud, and watch out for your invitation to the upcoming magazine event at the Royal Institution in October.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Age Of Unreason.

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2018 issue, The Age Of Unreason, asks are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Age Of Unreason” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F09%2Fage-of-unreason%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the age of unreason. Are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

With: Timandra Harkness, Ian Rankin, Sheng Keyi[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/09/age-of-unreason/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]