27 Apr 2018 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

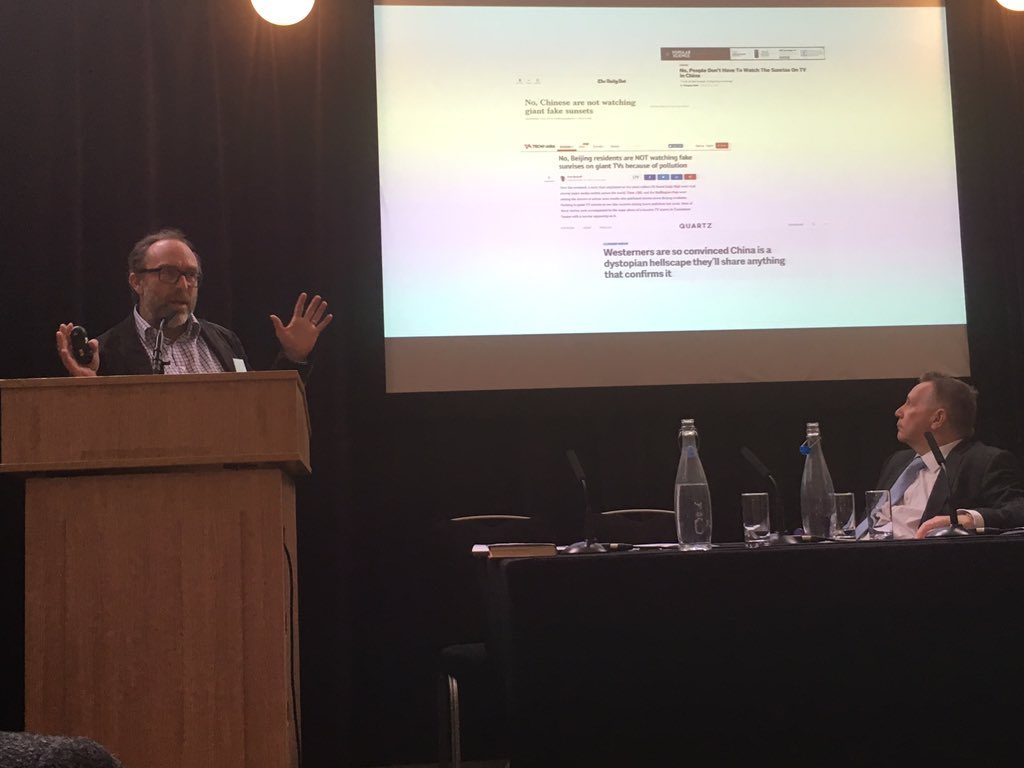

Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales speaking at Westminster Media Forum, April 2018. Credit: Daniel Bruce

“The advertising-only business model has been incredibly destructive for journalism,” said Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales at a Westminster Media Forum event on Thursday 26 April 2018 in London that looked at “fake news”.

“We need to resolve the incentives so that it makes sense and is financially sustainable to do good news,” Wales added.

Wales cited examples of false news stories that had been published on the Mail Online, such as an article featuring a projection of a perfect horizon in Beijing, erected as a way to compensate for the pollution, which proved fake, and a story claiming the Pope supported Donald Trump. He said the Daily Mail of 20 years ago was different. While not what he would choose to read, he thinks there is a place in the media landscape for tabloids, but one running fake news is “a quantum leap we should be very concerned about”.

Suggesting alternatives to advertising-only models, Wales said the Guardian’s donation request box (which he admitted he had consulted on) was an excellent example of how a media organisation can earn money without compromising standards. Meanwhile, a total paywall was very beneficial for some media, in particular financial media, with those readers valuing inside knowledge on the markets, though it would not suit all (the Guardian’s Snowden files, for example, were information he said he would want everyone to be able to access at the same time).

Wales’s concerns about the advertising-only, clickbait-style media models were echoed by others throughout the conference. Drawing an impressive panel of industry experts across media, law and tech, they all united in the view that while fake news meant a myriad of things to many different people, and was not something new, it was nevertheless problematic. Mark Borkowski, founder and head of Borkowski PR, spoke of the 19th-century great moon hoax and how “everything is different and everything is the same” before adding: “The speed at which we expect to get information, without proper fact-checking, is a plague.”

Nic Newman from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism proposed different ways for media to gain more trust, of which “slowing down” was one. Richard Sambrook, former director of global news at the BBC and now director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, said the rise in the number of opinion pieces over evidenced-based journalism was because they were cheaper to commission.

Better education about what constitutes good quality, reliable media was another solution proposed.

“Audiences need better education and sensitivity around algorithms,” said Kathryn Geels, from Digital Catapult.

Katie Lloyd, who is development director at the BBC’s School Report and who runs workshops around the country educating school children into news literacy, said there was a sense of urgency and confusion when it came to the topic and that teachers feel like it really needs to be taught.

“Young people are on the one hand savvy and on the other not so much and need extra help,” said Lloyd, adding that of those children she had interacted with, most knew what fake news was in principle, but not how to spot it.

“When we started talking to teachers they said they didn’t have the tools and the skills to teach it,” she added, tapping into a point raised by head of home news and deputy head of newsgathering at Sky, Sarah Whitehead, who said media education was just as important for older people as it was for the young, as the world of online was not the domain of only one group.

Lloyd also explained that diversity was essential when it came to who was delivering news as people were more likely to trust news from those they could relate to. This was in response to an audience member saying they had spoken to school children who expressed that they respected news on Vice over the BBC. Lloyd agreed that it was essential for news organisations to have a wide range of people in terms of age and background. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524822984082-ad9d065c-d104-5″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Apr 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet has a history of tangling with the country’s governments.

We, the undersigned freedom of expression and human rights organisations, strongly condemn last night’s guilty verdicts for staff and journalists of Cumhuriyet newspaper and note the harsh sentences for the defendants. The verdict further demonstrates that Turkey’s justice system and the rule of law is failing: this was a trial where the ‘crime’ was journalism and the only ‘evidence’ was journalistic activities.

While three Cumhuriyet staff were acquitted, all the remaining journalists and executives were handed sentences of between 2 years, 6 months and 8 years, 1 month. Time already served in pretrial detention will likely be taken into consideration, however all will still have jail terms to serve, and those with the harshest sentences would still have to serve approximately 5 years. Travel bans have been placed on all defendants, barring the three that were acquitted, in a further attempt to silence them in the international arena.

Several of our organisations have been present to monitor and record the proceedings since the first hearing in July 2017. The political nature of the trial was clear from the outset and continued throughout the trial. The initial indictment charged the defendants with a mixture of terrorism and employment related offenses. However, the evidence presented did not stand the test of proof beyond reasonable doubt of internationally recognizable crimes. The prosecution presented alleged changes to the editorial policy of the paper and the content of articles as ‘evidence’ of support for armed terrorist groups. Furthermore, despite 17 months of proceedings, no credible evidence was produced by the prosecution during the trial.

The indictment, the pre-trial detention and the trial proceedings violated the human rights of the defendants, including the right to freedom of expression, the right to liberty and security and the right to a fair trial. Furthermore, the symbolic nature of this trial against Turkey’s most prominent opposition newspaper undoubtedly has a chilling effect on the right to free expression much more broadly in Turkey and restricts the rights of the population to access information and diverse views.

“We observed violations of the right to a fair trial throughout the hearings. Despite the defence lawyers arguing that the basic requirements for a fair trial, such as an evidence-based indictment, were lacking these arbitrary sentences were handed down in order to attempt to intimidate one of the last remaining bastions of the independent press in Turkey,” said Turkey Advocacy Coordinator, Caroline Stockford.

The defence team repeatedly relied on the rights enshrined in the Turkish Constitution, as well as the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, demonstrating the importance of European human rights law to Turkey’s domestic legal system.

“‘Journalism is not a crime’ was declared again and again by the defendants and their lawyers and yet, despite the accusations containing no element of crime, the defendants served a collective total of 9.5 years in pretrial detention, and were found guilty at the end of an unfair trial,” said Jennifer Clement, President of PEN International.

Speedy rulings on legal cases of Turkish journalists, which include the Cumhuriyet cases of Murat Sabuncu and others and staff writer Ahmet Şık cases, pending before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) are crucial. This is not only to redress the rights violations of the many journalists still languishing in detention, but also to defend the independence and impartiality of the judiciary itself in Turkey. The Cumhuriyet case and other prominent trials against journalists clearly demonstrate that the rule of law is totally compromised in Turkey then there is little hope for fair or speedy domestic judicial recourse for any defendant.

“The short three hours of deliberation by the judicial panel did not give the impression that the case was taken seriously. The 17 months during which there have been 7 hearings of this utterly groundless trial have damaged independent journalism in Turkey at a time when over 90% of the media is under the sway of the administration,” said Nora Wehofsits, Advocacy Officer, European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF).

The guilty verdicts against the Cumhuriyet journalists and executives must be overturned and the persecution of all other journalists and others facing criminal charges merely for doing their job and peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression must be stopped. The authorities must immediately lift the state of emergency and return to the rule of law. The independence of the Turkish courts must be reinstated, enabling it to act as a check on the government, and hold it accountable for the serious human rights violations it has committed and continues to commit.

In light of the apparent breakdown of the rule of law and the fact that Turkish courts are evidently unable to deliver justice, we also call on the ECtHR to fulfil its role as the ultimate guardian of human rights in Europe, and to rule swiftly on the free expression cases currently pending before it and provide an effective remedy for the severe human rights violations taking place in Turkey.

Furthermore, we call on the institutions of the Council of Europe and its member states to remind Turkey of its international obligation to respect and protect human rights, in particular the right to freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial, and to give appropriate priority to these issues in their relations with Turkey, both in bilateral and multilateral forums. In addition, the Council of Europe’s member states should provide adequate support to the ECtHR.

We also call on the European and International media to continue to support their Turkish colleagues and to give space to dissenting voices who are repressed in Turkey.

Amnesty International

Article 19

Articolo 21

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI)

English PEN

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Freedom House

Global Editors Network

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

International Press Institute (IPI)

Italian Press Federation

Norwegian PEN

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso – Transeuropa

Ossigeno per l’informazione

PEN America

PEN Belgium-Flanders

PEN Centre Germany

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN Netherlands

Platform for Independent Journalism (P24)

Reporters without Borders

Research Institute on Turkey

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

WAN-ifra[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Apr 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Brussels, 26 April 2018

OPEN LETTER IN LIGHT OF THE 27 APRIL 2018 COREPER I MEETING

Your Excellency Ambassador, cc. Deputy Ambassador,

We, the undersigned, are writing to you ahead of your COREPER discussion on the proposed Directive on copyright in the Digital Single Market.

We are deeply concerned that the text proposed by the Bulgarian Presidency in no way reflects a balanced compromise, whether on substance or from the perspective of the many legitimate concerns that have been raised. Instead, it represents a major threat to the freedoms of European citizens and businesses and promises to severely harm Europe’s openness, competitiveness, innovation, science, research and education.

A broad spectrum of European stakeholders and experts, including academics, educators, NGOs representing human rights and media freedom, software developers and startups have repeatedly warned about the damage that the proposals would cause. However, these have been largely dismissed in rushed discussions taking place without national experts being present. This rushed process is all the more surprising when the European Parliament has already announced it would require more time (until June) to reach a position and is clearly adopting a more cautious approach.

If no further thought is put in the discussion, the result will be a huge gap between stated intentions and the damage that the text will actually achieve if the actual language on the table remains:

- Article 13 (user uploads) creates a liability regime for a vast area of online platforms that negates the E-commerce Directive, against the stated will of many Member States, and without any proper assessment of its impact. It creates a new notice and takedown regime that does not require a notice. It mandates the use of filtering technologies across the board.

- Article 11 (press publisher’s right) only contemplates creating publisher rights despite the many voices opposing it and highlighting it flaws, despite the opposition of many Member States and despite such Member States proposing several alternatives including a “presumption of transfer”.

- Article 3 (text and data mining) cannot be limited in terms of scope of beneficiaries or purposes if the EU wants to be at the forefront of innovations such as artificial intelligence. It can also not become a voluntary provision if we want to leverage the wealth of expertise of the EU’s research community across borders.

- Articles 4 to 9 must create an environment that enables educators, researchers, students and cultural heritage professionals to embrace the digital environment and be able to preserve, create and share knowledge and European culture. It must be clearly stated that the proposed exceptions in these Articles cannot be overridden by contractual terms or technological protection measures.

- The interaction of these various articles has not even been the subject of a single discussion. The filters of Article 13 will cover the snippets of Article 11 whilst the limitations of Article 3 will be amplified by the rights created through Article 11, yet none of these aspects have even been assessed.

With so many legal uncertainties and collateral damages still present, this legislation is currently destined to become a nightmare when it will have to be transposed into national legislation and face the test of its legality in terms of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and the Bern Convention.

We hence strongly encourage you to adopt a decision-making process that is evidence-based, focussed on producing copyright rules that are fit for purpose and on avoiding unintended, damaging side effects.

Yours sincerely,

The over 145 signatories of this open letter – European and global organisations, as well as national organisations from 28 EU Member States, represent human and digital rights, media freedom, publishers, journalists, libraries, scientific and research institutions, educational institutions including universities, creator representatives, consumers, software developers, start-ups, technology businesses and Internet service providers.

EUROPE

1. Access Info Europe

2. Allied for Startups

3. Association of European Research Libraries (LIBER)

4. Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties)

5. Copyright for Creativity (C4C)

6. Create Refresh Campaign

7. DIGITALEUROPE

8. EDiMA

9. European Bureau of Library, Information and Documentation Associations (EBLIDA)

10. European Digital Learning Network (DLEARN)

11. European Digital Rights (EDRi)

12. European Internet Services Providers Association (EuroISPA)

13. European Network for Copyright in Support of Education and Science (ENCES)

14. European University Association (EUA)

15. Free Knowledge Advocacy Group EU

16. Lifelong Learning Platform

17. Public Libraries 2020 (PL2020)

18. Science Europe

19. South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

20. SPARC Europe

AUSTRIA

21. Freischreiber Österreich

22. Internet Service Providers Austria (ISPA Austria)

BELGIUM

23. Net Users’ Rights Protection Association (NURPA)

BULGARIA

24. BESCO – Bulgarian Startup Association

25. BlueLink Foundation

26. Bulgarian Association of Independent Artists and Animators (BAICAA)

27. Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

28. Bulgarian Library and Information Association (BLIA)

29. Creative Commons Bulgaria

30. DIBLA

31. Digital Republic

32. Hamalogika

33. Init Lab

34. ISOC Bulgaria

35. LawsBG

36. Obshtestvo.bg

37. Open Project Foundation

38. PHOTO Forum

39. Wikimedians of Bulgaria

CROATIA

40. Code for Croatia

CYPRUS

41. Startup Cyprus

CZECH REPUBLIC

42. Alliance pro otevrene vzdelavani (Alliance for Open Education)

43. Confederation of Industry of the Czech Republic

44. Czech Fintech Association

45. Ecumenical Academy

46. EDUin

DENMARK

47. Danish Association of Independent Internet Media (Prauda) ESTONIA

48. Wikimedia Eesti

FINLAND

49. Creative Commons Finland

50. Open Knowledge Finland

51. Wikimedia Suomi

FRANCE

52. Abilian

53. Alliance Libre

54. April

55. Aquinetic

56. Conseil National du Logiciel Libre (CNLL)

57. France Digitale

58. l’ASIC

59. Ploss Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (PLOSS-RA)

60. Renaissance Numérique

61. Syntec Numérique

62. Tech in France

63. Wikimédia France

GERMANY

64. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Medieneinrichtungen an Hochschulen e.V. (AMH)

65. Bundesverband Deutsche Startups

66. Deutscher Bibliotheksverband e.V. (dbv)

67. eco – Association of the Internet Industry

68. Factory Berlin

69. Initiative gegen ein Leistungsschutzrecht (IGEL)

70. Jade Hochschule Wilhelmshaven/Oldenburg/Elsfleth

71. Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT)

72. Landesbibliothekszentrum Rheinland-Pfalz

73. Silicon Allee

74. Staatsbibliothek Bamberg

75. Ubermetrics Technologies

76. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt (Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg)

77. University Library of Kaiserslautern (Technische Universität Kaiserslautern)

78. Verein Deutscher Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare e.V. (VDB)

79. ZB MED – Information Centre for Life Sciences

GREECE

80. Greek Free Open Source Software Society (GFOSS)

HUNGARY

81. Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

82. ICT Association of Hungary – IVSZ

83. K-Monitor

IRELAND

84. Technology Ireland

ITALY

85. Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights

86. Istituto Italiano per la Privacy e la Valorizzazione dei Dati

87. Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD)

88. National Online Printing Association (ANSO)

LATVIA

89. Startin.LV (Latvian Startup Association)

90. Wikimedians of Latvia User Group

LITHUANIA

91. Aresi Labs

LUXEMBOURG

92. Frënn vun der Ënn

MALTA

93. Commonwealth Centre for Connected Learning

NETHERLANDS

94. Dutch Association of Public Libraries (VOB)

95. Kennisland

POLAND

96. Centrum Cyfrowe

97. Coalition for Open Education (KOED)

98. Creative Commons Polska

99. Elektroniczna BIBlioteka (EBIB Association)

100. ePaństwo Foundation

101. Fundacja Szkoła z Klasą (School with Class Foundation)

102. Modern Poland Foundation

103. Ośrodek Edukacji Informatycznej i Zastosowań Komputerów w Warszawie (OEIiZK)

104. Panoptykon Foundation

105. Startup Poland

106. ZIPSEE

PORTUGAL

107. Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais (D3)

108. Associação Ensino Livre

109. Associação Nacional para o Software Livre (ANSOL)

110. Associação para a Promoção e Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação (APDSI)

ROMANIA

111. ActiveWatch

112. APADOR-CH (Romanian Helsinki Committee)

113. Association for Technology and Internet (ApTI)

114. Association of Producers and Dealers of IT&C equipment (APDETIC)

115. Center for Public Innovation

116. Digital Citizens Romania

117. Kosson.ro Initiative

118. Mediawise Society

119. National Association of Public Librarians and Libraries in Romania (ANBPR)

SLOVAKIA

120. Creative Commons Slovakia

121. Slovak Alliance for Innovation Economy (SAPIE)

SLOVENIA

122. Digitas Institute

123. Forum za digitalno družbo (Digital Society Forum)

SPAIN

124. Asociación de Internautas

125. Asociación Española de Startups (Spanish Startup Association)

126. MaadiX

127. Sugus

128. Xnet

SWEDEN

129. Wikimedia Sverige

UK

130. Libraries and Archives Copyright Alliance (LACA)

131. Open Rights Group (ORG)

132. techUK

GLOBAL

133. ARTICLE 19

134. Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

135. Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT)

136. COMMUNIA Association

137. Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA)

138. Copy-Me

139. Creative Commons

140. Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

141. Electronic Information for Libraries (EIFL)

142. Index on Censorship

143. International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

144. Media and Learning Association (MEDEA)

145. Open Knowledge International (OKI)

146. OpenMedia

147. Software Heritage

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524750347203-f1e70660-87dd-9″ taxonomies=”1908″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]