[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

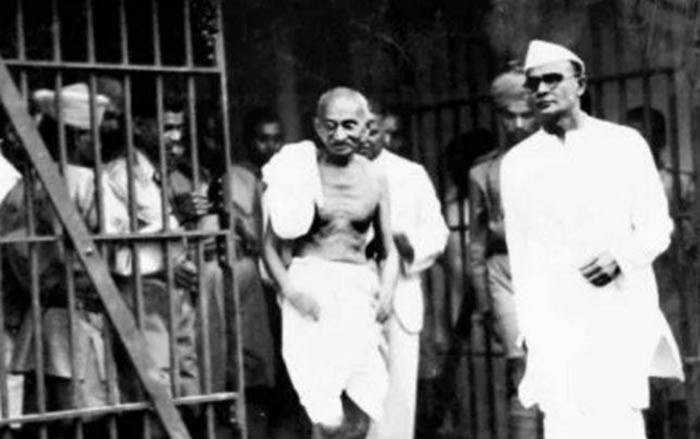

Mahatma Gandhi during his trial for sedition in Match 1922.

It’s been 72 years since India gained independence from Britain, but sedition remains entrenched not only in law (Section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code), but also in the mindset of successive governments.

In 1922, Mahatma Gandhi, leader of the Indian independence movement, was tried and prosecuted for “bringing or attempting to excite disaffection towards the British Government established by law in British India”, under Section 124-A.

“Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law,” Gandhi said while on trial. “If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote, or incite to violence.”

“Sedition was made an offence under the Indian Penal Code of 1860 which was drafted by [British Whig politician] Thomas Macaulay,” Suhrith Parthasarathy, a lawyer and writer based in Chennai, India, tells Index on Censorship. “It was unquestionably a weapon at the hands of the colonial government.”

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, and other prominent figures believed sedition should have no place in the newly independent India’s law books, Parthasarathy adds, “but unfortunately no elected government has thought it necessary to amend the IPC and delete Section 124-A”.

The authorities in India today are using Section 124-A to stifle dissent. A Manipur student activist was arrested over a social media post on the contentious Citizenship Bill, 14 students of Aligarh Muslim University were arrested for raising anti-national slogans on campus, and four students of Kashmiri origin in Rajasthan were charged with sedition over social media posts about last month’s terror attack in Jammu and Kashmir.

Parthasarathy says it is difficult to predict the outcome of these ongoing cases. “Instances of conviction where people have had to face imprisonment for sedition are rare,” he adds. “But the process is often a greater punishment — people accused of the offence face imprisonment and a trial, which can be long, arduous and hugely chilling.”

Section 124-A criminalises anyone who “through words, either written or spoken, or by signs, or by visual representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government”, with the term disaffection meaning “disloyalty and all feelings of enmity”.

The misuse of sedition law is not specific to any one political party in India. Since independence, many writers, activists and cartoonists have been accused of sedition by governments across the country as a response to legitimate criticism.

In the 1962 case of Kedar Nath Singh v State of Bihar, the Supreme Court of India, upholding the constitutional validity of 124-A, ruled that a person could be prosecuted if they “incitement to violence or intention or tendency to create public disorder or cause disturbance of public peace”.

In its third attempt to determine the validity of sedition, earlier last year, the Law Commission of India observed that while dissent is essential to any democracy, law enforcement agencies must use sedition law judiciously. Additionally, it also held that it is necessary for the Supreme Court to interpret the provisions of sedition law. The report also notes that the United Kingdom has itself abolished its own law on sedition almost a decade ago. While the powers of the Law Commission of India are limited to providing suggestions and recommendations only, the Parliament of India, the lawmaking body of the government, and the judiciary, the custodian of human rights, ought to revisit the justification of this provision.

With the indiscriminate use of archaic laws for dissenting against the government, many have raised their voices against such arbitrary restrictions on the fundamental right to free speech and expression, which is granted under the Constitution of India. Given the record of the ruling party in the last four years, intolerance of criticism is only seeing a rise in the country with authorities clamping down on free speech behind the garb of disloyalty and anti-national sentiments.

In 2015, Section 66A of the Information Technology Act 2000, which criminalised online speech considered “grossly offensive”, “menacing”, and caused “annoyance”, was struck down as unconstitutional due to the ambiguity of such terms. The Supreme Court of India held that any restrictions on speech could only be deemed reasonable under Section 19(2) of the Constitution of India. While the sedition law suffers a similar problem with definition, along with a lack of procedural safeguards, the Supreme Court has argued time and again that seditious words or actions are likely to threaten public order or incite violence, which is a reasonable restriction on free speech.

In data submitted to the Parliament of India by the Ministry of Home Affairs, which is in charge of law and order in the country, between 2014 and 2016, the first three years of the current government’s time in power, 179 people were arrested on the charge of sedition with only two convictions. This leads many to believe that authorities are abusing the law to stifle dissent and harass those who speak out.

There is a growing demand for amending the sedition law or repealing this relic of the past. However, there is an urgent necessity to first address the systemic flaws to ensure that these laws are not misused so as to mock free speech in India.

“The only amendment that we need on sedition is to remove Section 124-A, which parliament, if it has the will, can easily do,” Parthasarathy says. “P Chidambaram of the Indian National Congress has said recently that if the congress comes to power they’ll remove section 124-A from the IPC. But we have to ask the congress why they hadn’t thought of removing it earlier.” With a general election due to take place on 11 April, congress’s manifesto committee has promised to repeal sedition law.

“I would be very pessimistic of change coming from parliament,” Parthasarathy concludes. “Perhaps one day the Supreme Court will reconsider its 1962 verdict and strike Section 124-A down, for it unquestionably violates the right to freedom of speech and expression.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1553177738983-78591bd7-912e-5″ taxonomies=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row]