21 Sep 2018 | Albania, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

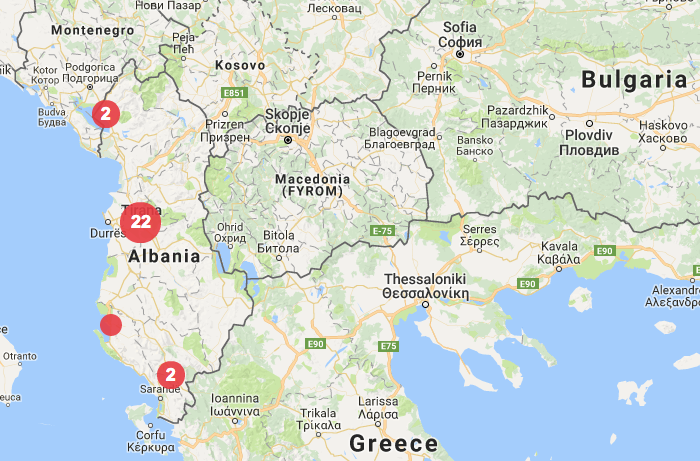

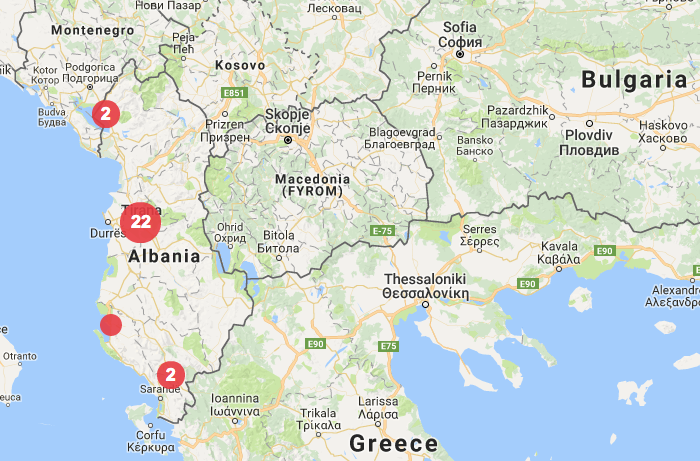

A small protest by journalists and citizens after the attack on Klodina Lala’s parental home. Credit: Fjori Sinoruka

In the early hours of 30 August, investigative journalist Klodiana Lala’s parental home was sprayed with bullets. Luckily no one was injured.

Lala, a crime reporter for Albania’s News 24 TV, connected the incident with her work as a journalist, saying that neither she nor her family had any personal conflicts that would spur this type of incident. The attack drew rapid condemnation and calls to bring the perpetrators to justice from concerned citizens and politicians, including the country’s prime minister, Edi Rama, who described it as a “barbarous” act. He pledged that the authorities would spare no efforts to investigate the attack.

Rama’s fine words about this attack belie the reality of most crimes against journalists in Albania: identification and prosecution rates of perpetrators are near zero.

When City News Albania’s editor Elvi Fundo was brutally assaulted at 11am in crowded central Tirana, he too received solidarity from the country’s politicians and press, including a note from Rama. But 17 months later, those expressions of support haven’t translated into action from prosecutors.

The attack on Fundo, in which he was beaten with iron bars by two men in hoodies just metres from his office, left him unconscious with serious injuries to his head and an eye.

To add insult to his injuries, Fundo was told on 31 August 2018 that prosecutors were suspending the investigation into his assault because of the lack of suspects.

“This is a grotesque decision. Investigations are not conducted thoroughly. I had to force authorities to seek out more footage from the bars around the area after I left the hospital. They didn’t seem very keen to do so,” he said.

Fundo’s lawyer challenged the decision in court, emphasising that he has given prosecutors information, he said, that can lead investigators to those that ordered the attack.

“I will never stop pushing them to bring the authors of the assault on me to justice since this is not a case lacking in information. I believe the police and prosecutors are just afraid of those who ordered the attack on me,” he said.

While intimidation is a criminal offence in Albania and is punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison, journalists find themselves without much support when they are threatened due to their professional duties.

Very often, prosecutors are reluctant to even open a case and when they do are eager to drop the charges, as was the case against a man who threatened a journalist on Facebook.

Dashamir Bicaku, a crime reporter who acted as a fixer and translator for a Daily Mail journalist, received an anonymous threatening message on June 17 2018 via his Facebook account. The threat came two days after the Mail published an investigation into Elidon Habilaj’s fraudulent asylum claim and subsequent career in British law enforcement, for which Habilaj was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in absentia.

“I’ll come straight to the point! I’ll come and get you so that there’ll be nothing left of you and yours!”, the message read. He reported the incident to the police the next day, alleging to law enforcement that Habilaj was the only person who would have a motive to threaten him.

But on 31 July 2018, he received a letter from the Vlora prosecutor’s office telling him that they had decided not to open an investigation into the case. According to Bicaku, the prosecutors said that Habilaj had denied sending a threatening message to the journalist and — even if he had — the message was not serious.

A few days later Bicaku learned that a close relative of Habilaj was working as a prosecutor in the same unit.

“What happened is a clear signal about the connections that those involved in organised crime have with people in the justice system,” Bicaku said.

Even when the aggressor has been clearly identified, negligence by the investigating institution makes appropriate punishment difficult.

Julian Shota, a correspondent of Report TV, was threatened with a gun by Llesh Butaku, the owner of a bar in the town of Lac where an explosion had taken place. When the journalist identified himself, Butaku demanded that he leave and not report the incident. When Shota refused, Butaku loaded a gun and pointed it at the journalist’s head.

Shota said he was saved by Butaku’s relatives, who grabbed his hand to prevent him from shooting. The journalist immediately reported the incident to police, but three hours passed before they arrived to detain Butaku.

“In three hours you can hide a rocket let alone a handgun,” Shota said. “The prosecutor received me in his office telling me clearly that I should not expect a lot since no gun was found on him.”

After seven hours Butaku released and the charge for illegal possession of firearms, which could have carried a prison sentence, was dropped.

“Instead of being investigated for attempted murder, Butaku is only being investigated for making threats,” he said.

Artan Hoxha, a prominent investigative journalist with over 20 years of experience, remembers tens of case when he was threatened because of his job, but that “every single case was suspended without any success”.

“I rarely report the threats that I receive to the authorities anymore. I know it is not worth even to bother doing so,” he said.

Part of the problem is that the Albanian judicial system is considered one of the most corrupt in Europe. It is currently undergoing a radical reform overseen by international experts in which all the country’s judges and prosecutors are being put through a vetting process.

As of August, 45 judges and prosecutors have been evaluated. Twenty-one failed and will be unable to continue to work in the judicial system.

Dorian Matlija, attorney and executive director at Res Publica, a centre for transparency, considers the prosecution the most problematic branch of the judicial system.

“Journalists are right, the prosecution is infamous for its bad work and it is one of the less scrutinised institutions over its decisions despite having a lot of power within the system,” he said.

According to Matlija, when journalists received death threats or are sued, they often find themselves alone.

“They have difficulties accessing and navigating the judicial system while the media owner is often the first to abandon them to keep trouble at bay,” Matlija said.

To remedy this, he said that is very important to create free legal help for journalists, not only when they face prosecution, and also to push for employment rights.

Journalists consider the lack of judicial protection a big obstacle in continuing doing investigative journalism in Albania.

“Is very difficult to investigate organised crime in Albania, since you don’t have the minimum protection and media owners can throw you out in the first place,” Bicaku said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1537456192915-fc339c8f-4676-3″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Albania’s mainstream media outlets have been reluctant to cover and expose corruption in the country, and observers blame vexatious lawsuits for the hesitancy.

In June 2017, Gjin Gjoni, a court of appeals judge in Tirana, and his wife Elona Caushi, a businesswoman, filed charges against BIRN Albania along with its journalist Besar Likmeta and Aleksandra Bogdani, and separate charges against the newspaper Shqiptarja, along with its journalists Adriatic Doci and Elton Qyno.

BIRN Albania, which specialises in investigative reporting, publishing and media monitoring, along with Likmeta and Bogdani were accused of causing the couple reputational damage and anguish, for which Gjoni and Caushi are demanding 7 million Lek (€54,000) in compensation.

The BIRN Albania journalists had written about the closure and subsequent reopening of an investigation, carried out by the High Inspectorate for Declaration and Audit of Assets and Conflicts of Interest, into Gjoni for concealing wealth, falsifying official documents and money laundering.

In another article, BIRN Albania listed Gjoni as one of the ten richest judges in the country.

In a separate lawsuit, Gjoni and Caushi, based on the same reference, are asking for 4 million Lek (€30,000) in compensation from Shqiptarja, Doci and Qyno.

Kristina Voko, the executive director of BIRN Albania, considers the lawsuit malicious in nature. She pointed to the high journalistic standards held by the organisation for the work it produces.

“We are confident we will win the case because our reporting has been in public interest and solidly based on facts,” she told Index.

Doci wrote on Facebook that he was honoured by the lawsuit and that he would not remove anything in his article about Gjoni because he considers it to be accurate.

Media organisations within the country and internationally have expressed solidarity with BIRN Albania and Shqiptarja. Many think the cases will further discourage investigative journalism, which is already scarce.

Flutura Kusari, a media lawyer, said in an article published at the website Sbunker that the Gjoni lawsuits fell under the category of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP), which she believes are being used to intimidate Albanian journalists.

“In the SLAPP lawsuits you can see prima facie that are not based in facts and they are going to be unsuccessful in the court. With them the plaintiff does not aim to win the case, but aims to frighten and discourage journalists from further reporting issues of public interest, making them pass through long and costly court processes,” she wrote.

The Union of Albanian Journalists called for Gjoni to stand down while the case is ongoing as his position in the judicial system may influence the decisions.

Blendi Salaj, the vice chairman of Albanian Media Council, considers the case as one against investigative journalism that also aims to keep the media silent.

“There are no grounds for this case but the fact that true journalism and the dissemination of information goes against the interest of subjects whose shifty activities are revealed in the press,” he told Index.

Salaj also pointed to the large damages requested as compensation by the plaintiff.

“The amount of money they request is meant to scare, worry and intimidate journalists and outlets that expose facts they don’t want out there,” he said.

Kristina Voko also agrees that lawsuits are being used as a form of intimidation.

“It is true that during the last year, there has been an increased number of lawsuits against Albanian journalists or media outlets from judges or private companies involved in different concessionary agreements,” she told Index.

“This poses concerns related to media freedom in the country,” she said.

Investigating private companies also poses difficulties for journalists in the country. It is already a rare practice in the mainstream media as result of advertising contracts and strong ties that some of these companies have with politicians.

Albania has begun the implementation of an important judicial reform after almost two years of adopting laws that aim to clean up corruption in politics.

The reform was strongly pushed by the European Commission and the United States, and is considered crucial for Albania to advance in its bid to join the European Union.

A vetting process for all judges and prosecutors in the country supervised by an international body is underway as the first step to reform the system. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506959873796-92fda719-8e40-6″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Jun 2010 | Index Index, minipost

A Tirana court has ordered Albania’s Top Channel TV to pay €400,000 compensation to Ylli Pango, the former Minister of Culture, Tourism, Youth and Sport after broadcasting hidden camera footage of him, asking a female job applicant to remove her clothes. Investigative programme, Fiks-Tarif, had sent undercover reporters to investigate allegations that, whilst in office, Pango was offering employment in return for sexual favours. When giving judgement, the court said they found in favour of Pango because the recordings had been obtained illegally.

28 Jan 2025 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, News and features, Volume 53.04 Winter 2024

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

After three years of Taliban rule, nobody really believed women could be erased further from public life in Afghanistan.

“But the Taliban found another way: they’ve restricted our voices and faces,” said Maryam, an Afghan legal scholar and journalist.

Maryam, who uses a pseudonym, was referring to the Taliban’s “vice and virtue” laws, which were passed in August and ban women from speaking, singing or showing their faces in public. If women break the rules, they – or their male relatives – face imprisonment.

Maryam spoke to Index in hushed tones over Signal from the relative safety of her living room in Afghanistan.

The new laws typify the rapid intensification of the Taliban’s crackdown, which has already seen women banned from parks, workplaces, schools and universities since it took power in August 2021. Once implemented monthly, harsh laws, decrees, house raids and arrests are now a daily occurrence.

“It’s a very intense attack on the dignity of humans and the dignity of women,” said Shaharzad Akbar, executive director of Afghan rights group Rawadari. “Before, there was some wiggle room, but it’s very scary because now it’s law, it’s out there and people are required to comply with it.”

The crackdown isn’t manifesting just through new laws.

“The Taliban have also been destroying institutions and putting new institutions in place to actually implement and carry out their vision of society,” said Akbar. She should know, having chaired the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission before it was abruptly dismantled when the Taliban toppled Kabul.

At that time, Maryam was on the cusp of completing her legal training, having graduated from university, and working as an assistant lawyer in the country’s courts, often assisting on highly sensitive divorce and domestic violence cases that drew the ire of Taliban members.

After the takeover, the Taliban closed the country’s only bar association. All existing licences to practise law were revoked, putting lawyers out of work. Many like Maryam, who were still waiting for their licences to be formally approved, never received their documentation. As the Taliban filled the Ministry of Justice and the courts with its own lawyers, judges and prosecutors, Maryam’s chances of a legal career vanished.

Maryam was just a toddler when the Taliban was overthrown in 2001. Now 26 years old, she finds it hard speaking about the early “bad days” after the Taliban’s recent return to power and the subsequent unravelling of decades of progress on women’s rights.

She has relatives – mostly judges and their immediate families – who have managed to leave the country. Yet, like many Afghans, she’s not been deemed enough “at risk” to warrant evacuation. Instead, she’s focused on doing what she can while living under the constant threat of Taliban restrictions.

Through word of mouth, she established a homeschool teaching English to girls in her neighbourhood. It was one of the many underground schools that proliferated across Afghanistan after September 2021 when the Taliban issued a ban on girls over the age of 11 attending secondary school.

However, as rumours swirled about the rising number of secret schools, the authorities began doing door-to-door searches. She received messages over Telegram from Taliban fighters warning that she’d be thrown into jail if she didn’t stop “working against the regime”.

Maryam said she had no choice but to close the school.

“We already were in danger because of the position of my family in the justice system,” she said. “I didn’t want to make more danger for myself, my family or my students.”

In December 2022, the Taliban banned all Afghan women from attending university. Maryam’s husband, an engineer, was teaching at a local university, and he was devastated that his female students were being forced to give up their studies.

Under the most recent law, he faces losing his job if he leaves work to accompany Maryam anywhere. Without him, she’s forbidden from leaving the house.

The Taliban has created hundreds of positions for men to teach in gender-segregated religious schools – madrassas – across the country, while women with university degrees and teaching experience are forced to stay at home.

Rawadari – one of the few organisations that has maintained a network on the ground documenting violations of civil and political rights since the takeover – has been closely following the detrimental impact of the education ban on women’s and girls’ mental health across Afghanistan’s 34 provinces.

The overwhelming sense of ‘hopelessness’ is undeniable, said Akbar, who now lives in the UK in exile but still finds reports of what’s happening back home extremely difficult to hear.

“I think most of the girls believed this will be temporary and never imagined they would experience what their mothers had experienced,” she said. “They are depressed and they’re struggling to keep their hopes alive.”

Maryam continues to battle her own mental health struggles as a result of the restrictions, but has found some solace in working in the shadows as an online educator, mental health trainer, journalist and advocate.

However, as the internet and social media platforms are increasingly monitored by the Taliban and its spies, she has had to be more careful about her online interactions.

“I can’t trust who is safe and who is not,” she said. “There are women on Instagram and other places who are looking for women who are disobeying Taliban rule. For that reason, I don’t share anything about myself. They just hear my voice and the teachings I’m offering them. I’m scared and my colleagues are scared, but we go forward, do the job and provide teaching for those who need it.”

Unsilenced in exile

There is also growing momentum from Afghan women internationally to give their sisters inside the country a voice. One such woman is Qazi Marzia Babakarkhail, who became a judge in Afghanistan at 26 – the same age that Maryam is now.

Babakarkhail worked in the family courts, later setting up a small shelter for divorced women in Afghanistan and a school for Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Those initiatives were a lifeline to dozens of women, but they soon drew unwanted attention from the Taliban and she fled the country in 2008 after two assassination attempts.

Since moving to the UK, Babakarkhail has learnt English and now works as a caseworker for an MP near Manchester. As well as helping campaign for the evacuation of hundreds of female judges, she speaks daily to former colleagues and friends still trapped in Afghanistan.

Her advocacy earned her an invitation to an all-Afghan women’s summit held in Tirana, Albania, in September. It was the first time since the Taliban regained power that such a large group of Afghan women – more than 100 from across Europe, the USA, Canada and Afghanistan itself – had been given an international platform to discuss the rollback of women’s rights. They are so often excluded from conversations on Afghanistan’s future.

This marked a sharp contrast with a UN meeting held earlier in June in Doha, which was heavily criticised for inviting Taliban leaders and neglecting to bring Afghan women’s voices to the table.

Babakarkhail said the summit had opened ‘a new window of hope’ for Afghan women. Seeing women who defied the Taliban travel to Tirana reminded her of her own perilous journey and gave her hope for Afghanistan’s future.

“They are real activists because they are still fighting and still stay in Afghanistan,” she said. “Of course they do a lot of things silently, but they will go back. They know how to deal with the Taliban and they will keep silent. They made us proud.”

She is hopeful the summit – which discussed the unravelling human rights situation, the urgent need for humanitarian aid and international recognition of the Taliban’s mistreatment of women as “gender apartheid” – will provide the necessary wake-up call to the international community.

“We don’t want the United Nations or other countries to recognise the Taliban as a government,” she said. “This group is a stand against the Taliban and a stand for people in Afghanistan.”

Pushing for accountability

The international push for accountability, both at the International Criminal Court – which has an ongoing investigation into alleged crimes committed in Afghanistan – and the groundbreaking move to bring a gender persecution case against the Taliban at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) – are other signs that the dial may finally be shifting in Afghan women’s favour.

Akbar has been one of the leading voices campaigning to bring the case to the ICJ. Although she is appalled by what is happening to her motherland, she believes these judicial measures and the summit in Tirana will help ensure Afghan women’s voices are no longer silenced.

“We have a saying in Farsi,” said Akbar. “We say, ‘Drop by drop, you make a river.’ All of this will come together to become this river of hope and this river of defiance against the Taliban. The dream really is that we show the Taliban that the power of people everywhere in the world is with the women of Afghanistan and not with them.”

For Maryam, such developments are already reviving dreams that Afghan women’s rights and freedoms will one day be restored.

“I know that the suffering that women are enduring under the Taliban’s gender apartheid regime is unique,” she said.

She hopes the ongoing efforts, both by women like her inside the country and by those elsewhere in the world, will be enough.

“We are motivating and inspiring each other. We will win and the future will be ours – women’s.”