15 Jul 2025 | Iran, Israel, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Fatemeh Jamalpour: The cost of truth in Iran

When I was invited to co-write a story with an Israeli journalist, I asked myself: what could we possibly have in common? After 46 years of political hostility between the Islamic Republic and the State of Israel, it turned out we shared more than I expected. We are both inheritors of our countries’ proxy wars – and we both carry a shame that isn’t ours. It’s the shame of war-driven leaders, the shame of bombed hospitals and civilians buried beneath flags. Somehow, in that shared grief, shame became a point of connection.

Beyond the battlefield, we share something else: the impact of censorship and propaganda. Both governments declared the recent 12-day war – which left more than 930 people dead – a victory. But every civilian killed is not a victory; it’s a human life lost. In Iran, clerics have openly called for executions and mutilations of those who dare to criticise the Supreme Leader. Any dissent – even a tweet suggesting the Islamic Republic bears responsibility for the war – can lead to interrogation, summons or surveillance. In today’s Iran, truth has a cost – and more and more, that cost is freedom.

Starting on the fifth day of the Israel-Iran war, from 17-21 June, the Iranian regime imposed an almost complete internet shutdown, as reported by global internet monitor NetBlocks. Iranians were left not only without access to news but also without emergency alerts or evacuation warnings. The entire country was plunged into darkness – like a black hole – leaving defenceless civilians uncertain whether their neighbourhoods were in danger, or if they should flee.

Amid the chaos, parliament passed a law criminalising the use of Starlink internet.

“While they had cut off our internet – and during the war, I couldn’t get any news from my family and friends because both the internet and phone lines were down – I was sick with worry for every loved one,” said Leila, a 38-year-old woman from Shiraz. “And yet, when we try to access something that is our basic right, even after paying a hundred million tomans, we’re treated like criminals. These laws have no legitimacy.”

Meanwhile, the regime began targeting journalists’ families. Several relatives of reporters working with Persian-language outlets abroad, such as BBC Persian, were arrested, threatened, and labelled “enemies of God” – a charge that carries the risk of execution.

“I barely post on social media anymore because the space is under intense surveillance by security agents, and the pressure on journalists is suffocating,” said Raha Sham, 41, a parliamentary reporter in Tehran. “Many of my colleagues have received threatening phone calls. The tone is harsh, the intent clear: delete your tweets, your stories, your posts – or face the consequences.”

Iranians now face a new wave of repression in the aftermath of the war. Across cities, new checkpoints have sprung up where security forces stop civilians and search their phone photo galleries – often without a warrant. At the same time, parliament has passed new legislation effectively criminalising anti-war activism.

“Anti-war activism is a legitimate form of civic engagement, and criminalising it is both unjust and unlawful,” a human rights lawyer in Tehran who prefers to stay anonymous told me. “What disturbs me most about the post-war crackdown is that a spirit of vengeance has taken over the judiciary. Judges now seem to think their role is to avenge those who were killed. The mindset is: ‘Our commanders have died – someone must pay.'”

But the problem doesn’t end with the state. While we’re silenced by our government, we’re also erased by much of the Western media. For many editors, it’s always about numbers, not names. They want statistics, not stories. When Western journalists do gain access, they often report only from regime-approved rallies, while just a few streets away, anti-war protests and underground art scenes go unseen.

We’re rarely shown in full light. Middle Easterners remain blurred, devout, anonymous. After years of contributing to Western outlets, I’ve learned this isn’t an accident. It’s not just regime control. It’s also the residue of a colonial gaze – still shaping coverage in 2025.

David Schutz: Control of the press in Israel

In Israel, I was under missile fire too. While everyone else huddled in shelters, glued to the news, I stood on my roof watching what looked like fireworks. But if you Google “Iranian missile hit Tel Aviv Stock Exchange” in Hebrew, you’ll find nothing – you have to know where to look to piece together the truth.

Israel’s media has always been tightly controlled: military censors, a three-second delay on live broadcasts – a well-known fact that has been confirmed by inside sources. Today it’s slicker but more repressive than ever as global opposition to Israeli policies grows. The Israeli Journalists Association said recent moves by the government “seek to eliminate free media in Israel”. But it’s worth asking whether the press here was ever truly free.

Even before 7 October 2023, it operated under a mesh of dependent commercial interests and state funding with the military and government in what journalist Oren Persico from The Seventh Eye, an independent investigative magazine focused on the media in Israel, described as a “symbiotic relationship”.

After the election of the current government in 2022, bills have been brought forward that weaken public broadcasting, including proposals to give the government increased control of the public broadcaster’s budget – effectively letting the government starve it of funds should coverage stray too far.

“Very often, journalists effectively act as representatives for the institutions they cover: legal affairs reporters serve the prosecution and the judicial system, economic reporters serve the Finance Ministry, and military reporters naturally represent the positions of the IDF [Israel Defense Forces],” Persico said.

My friend Sapir runs a WhatsApp group called Demanding Full Coverage for Gaza.

“Almost nothing about Gaza’s humanitarian catastrophe gets through to the Israeli public. Not because the information doesn’t exist, but because editors don’t cover it – and when they do, briefly, the military and government have a well-honed strategy to muddy the waters,” she said.

When Haaretz reported at the end of June that Israeli soldiers had been ordered to fire on civilians at an aid centre, counter-reports appeared almost immediately in multiple outlets – often repeating the same phrasing, the same anonymous interview – claiming “Hamas gunmen” had fired on crowds. The effect was the same: to muddy the story and deny a pattern of conduct.

“The goal is to flood the market with information so people think there’s no way to know what’s true anymore, to make them give up looking,” Sapir said.

Andrey X, an independent Israeli journalist, explained that all security-related stories must legally be cleared by military censors before publication. This can be justified on security grounds in some cases but critics argue it adds a significant challenge to media freedom. In practice, most outlets ignore this – until the government decides to enforce it retroactively, as in the case of American journalist Jeremy Loffredo, who was detained for four days and threatened with jail time over his reporting for The Grayzone, showing the locations of the military targets of Iranian missiles.

Footage of Israeli vehicles and homes hit by Israeli Hellfire missiles and tank shells on October 7 were labelled “Hamas attacks”. A government spokesman admitted 200 Hamas fighters were misidentified as civilians.

Twenty months later, Gaza is a demolished wasteland of dust and decay. The military releases sparse reports of “accidents”, just enough to recast outrage as tragic inevitability rather than accountability, enabling ongoing abuses without meaningful scrutiny.

Cable news will mention that the army had “begun food distribution”, but in such vague, antiseptic terms that few readers realise this means just a handful of stations, a framing that distorts what is actually happening and why.

Softer repression is often more powerful. Journalists fear being fired or defunded for not toeing the military spokesman’s line. Many fear public backlash even more: boycotts, pulled advertising and social media campaigns branding them traitors. Mildly subversive correspondents have faced on-air abuse – often in deeply personal terms – from their colleagues, as detailed by Persico when he spoke with me.

For Palestinian journalists, the dangers are greater still. Reporting on police or military abuses can end careers or worse. Even inside Israel, Arab reporters face social hostility, public threats and constant suspicion about their loyalty. The same event, covered by an Israeli and a Palestinian journalist, carries different risks, but that gap is always narrowing.

Each day, more people choose to shed the ideological masks their states have forced upon them in ’48 Palestine, Israel and Iran. Despite relentless propaganda and censorship, the number continues to grow. The future of our countries will not belong to war-hungry leaders – it is being shaped from the ground up, in the streets and in the digital space. In this age, every post, every story, every tweet by ordinary citizens is a quiet act of resistance – a revolution in itself.

This piece is published in collaboration with Egab, an organisation working with journalists across the Middle East and Africa

2 Jul 2025 | Iran, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Newsletters

As I wrote the newsletter last week we were closely following events in Iran but didn’t have a full picture in terms of free speech ramifications, in part because of censorship itself – internet blackouts and media bans meant that information was slow to leave the country. One week on, it’s different. Many alarming stories have emerged.

The conflict between Israel and Iran was of course marked from the start by free speech violations – early on there was the bombing of Iranian state television. Then later there were strikes on Tehran’s Evin Prison. While these acts may have been intended as symbolic blows against key institutions of Iranian repression, the consequences were grimly real: media workers killed, political prisoners endangered. And in between? Lots of repression.

At Index, some developments were personal, including when our 2023 Arts Award winner – the rapper Toomaj Salehi – disappeared for three days. Beyond our immediate network, according to the Centre for Human Rights in Iran, more than 700 citizens have been arrested in the past 12 days, some for alleged “espionage” or “collaboration” with Israel. There have also been six executions on espionage charges carried out, with additional death sentences expected.

The Supreme Council of National Security announced that any action deemed supportive of Israel would be met with the most severe penalty: death. The scope was broad, ranging from “legitimising the Zionist regime” to “spreading false information” or “sowing division”.

As mentioned above, Iran also began restricting internet access before shutting down access altogether. Officials claimed the blackout was necessary to disrupt Israeli drone operations allegedly controlled through local SIM-based networks. The result: ordinary Iranians were cut off from vital news. International journalists from outfits like Deutsche Welle (DW) were banned from reporting inside Iran. The family of a UK-based journalist with Iran International TV was even detained in Tehran, in an attempt to force her resignation. Her father called her under duress, parroting instructions from security agents: “I’ve told you a thousand times to resign. What other consequences do you expect?”

Yet amid the bleakness, there have been a few positive instances. Iranian state media aired a patriotic song by Moein, a pop icon long exiled in Los Angeles. Some billboards replaced religious slogans with pre-Islamic imagery, such as the mythical figure Arash the Archer. There has also been an unexpected digital reprieve: on Wednesday, following the agreement of an Israel-Iran ceasefire deal brokered by the US administration the day before, Iranians reported unfiltered access to Instagram and WhatsApp for the first time in two years.

Given everything else it feels unlikely that this openness will last. This week’s proposals by Iran’s judiciary officials to expand espionage laws and increase the powers of Iran’s sprawling security apparatus imply as much, too. So while the world’s eyes might have moved away from Iran, our gaze is still there – documenting the free speech violations and campaigning for their end.

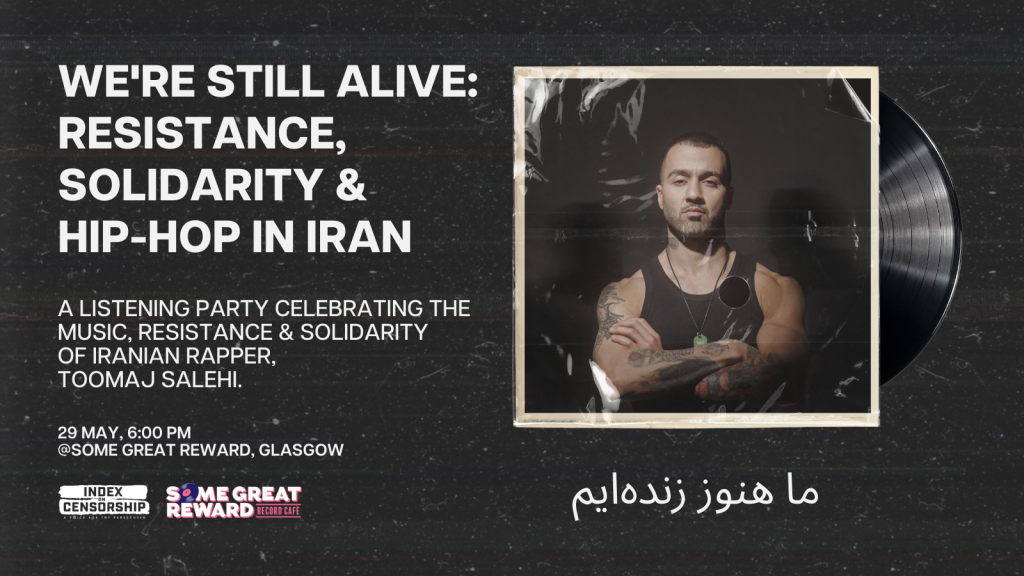

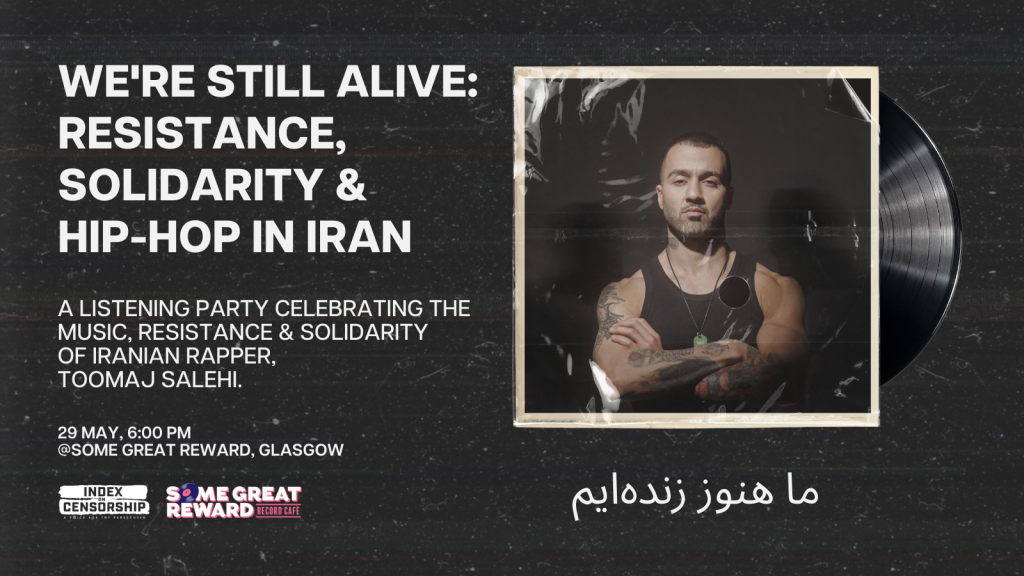

9 May 2025

Join Index on Censorship and Some Great Reward for a Listening Party celebrating the music, resistance and solidarity of Iranian rapper, Toomaj Salehi.

Toomaj is a Farsi-language rapper who has never shied away from using his music to stand up for those raising their voices calling for human rights and democracy in Iran. For his courage and music, he has long been persecuted by the Iranian regime – facing harassment, surveillance, imprisonment and a death sentence as a result.

Toomaj has been persecuted for his music so there is no more powerful way to stand in solidarity with him than to celebrate his music. That is why we are inviting music fans to come together on the southside of Glasgow to share his songs, learn about his life and stand in solidarity with him and everyone in Iran standing up for human rights and democracy. This is not a ticketed event – just turn up.

About Toomaj Salehi’s persecution

Over the last four years, Toomaj has faced continuous judicial harassment, including arrest and imprisonment. He has been more intensely targeted following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody September 2022, when he became a vocal supporter of the Women, Life, Freedom movement. After publishing songs in support of the courageous protesters and taking part in the protest himself he was arrested and sentenced to over 6 years in prison. On 18 November 2023, Toomaj was released on bail. But his freedom was not to last.

Days later he was rearrested after he uploaded a video to YouTube documenting his treatment and torture while in detention. In April 2024, an Iranian court sentenced him to death on charges of “corruption on earth”. It took the Supreme Court to intervene to quash the death sentence, leading to Toomaj being released from prison in December 2024.

14 Mar 2025 | Iran, Statements

On 13 March 2025, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (“UNWGAD”) issued an opinion declaring that Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi’s detention of more than 753 days was arbitrary and in violation of international law. A joint petition was submitted to the UNWGAD by the Human Rights Foundation, Doughty Street Chambers, and Index on Censorship in July 2024.

Mr Salehi has been subjected to a sustained campaign of judicial harassment by Iranian authorities, which has included periods of imprisonment, arrest, torture, and a death sentence. His treatment was the result of his music and activism in supporting protest movements across Iran.

Mr Salehi was first arrested in October 2022, after he released a song supporting the protests that followed Mahsa Amini’s death in custody. After an extended period of pre-trial detention, including significant time spent in solitary confinement, Mr Salehi was sentenced to six years and three months’ imprisonment for charges including “corruption on earth”, as well as being banned from leaving Iran for two years.

Mr Salehi was temporarily released in November 2023 but was rearrested only 12 days later, after posting a video detailing the torture he endured. In April 2024, he was sentenced to death. His death sentence was overturned by Iran’s Supreme Court in June 2024. Shortly after, two further cases were filed against Mr Salehi based on his new song, Typhus. In December 2024, Mr Salehi was released from prison, although the two most recent cases remain on foot.

In its opinion, the UNWGAD found that there was a clear pattern of discrimination against Mr Salehi on the basis of his political opinions and as an artist expressing dissent. The UNWGAD said that “ultimately, the song, social media posts, and video were forms of Salehi’s exercise of his freedom of expression”, and concluded that he had been targeted primarily for these forms of speech. The UNWGAD had particular regard to the vague and overly broad “corruption on earth” charge, observing that none of Mr Salehi’s alleged crimes fall under it.

The UNWGAD’s opinion also noted that Mr Salehi wasn’t tried by a public or independent court and was given limited access to his lawyer. Even when he was able to contact his lawyer, the calls were monitored. The UNWGAD expressed grave concern about the torture that Mr Salehi endured during his detention and the brief period of enforced disappearance, and indicated particular concern about the use of torture to compel a confession.

In response to the opinion, Mr Salehi’s cousin, Arezou Eghbali Babadi, said:

“What is happening under the Iranian regime against those who stand for their rights is a direct assault on human dignity and justice. Those in power manipulate the system to silence voices of truth, leaving individuals defenseless. With no safeguards, no accountability, and no limits to their violence, every moment is uncertain. This is not just about Toomaj but it is about a nation’s struggle against fear. This cruelty can be inflicted for something as simple as singing a song or sharing a post. There is an urgent need for the world to stand against tyranny. This opinion by the UNWGAD is an important step towards that goal.”

Nik Williams, campaigns and policy officer at Index on Censorship said:

“For years, Toomaj has faced persecution for his music, activism and solidarity with the courageous women of Iran and everyone standing up for human rights in the country. We welcome this opinion from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, which is an important and timely reminder of the need for continued international support and pressure to ensure he remains free and able to continue his music.”

Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC, international counsel for Mr Salehi’s family, Index on Censorship, and the Human Rights Foundation, said:

“Our brave, brilliant client, Toomaj Salehi, stood firm as Iranian authorities targeted him – with arrests, 753 days’ imprisonment, torture, and a death sentence – and fearlessly maintained his basic right to express himself through his art. His has been an important voice in the push by Iranian people for recognition of their human rights.

Now the UN Working Group’s Opinion confirms the unlawfulness of Mr Salehi’s treatment. It underscores the need to ensure that Mr Salehi remains free, and is not again subjected to arbitrary and unjust treatment by the State. It is a welcome and timely reminder for Iranian authorities that they will be held to account for their actions.”

Claudia Bennett, legal and programme officer at Human Rights Foundation said:

“The UNWGAD’s decision is not just a victory for Toomaj but for all prisoners of conscience in Iran. His case exemplifies the Iranian regime’s intolerance of any criticism, even in the form of art. This decision highlights the alarming reality that a simple song can lead to an absurd charge like ‘corruption on earth’ in Iran, a crime punishable by death. With this decision, the Iranian regime must understand that if it continues to deprive Iranian citizens of their most basic rights and freedoms, the international community will hold it accountable.”

Any press queries for Index on Censorship should be directed to Nik Williams on [email protected].

More background about Toomaj Salehi is available on social media, at @OfficialToomaj (X) and @ToomajOfficial (Instagram). More details of the campaign can be found at #FreeToomaj.