Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Sentence has now been upheld in a devastating blow for free speech. Lauren Davis reports

Sentence has now been upheld in a devastating blow for free speech. Lauren Davis reports

(more…)

UPDATE: Paul Chambers appeal of his twitter conviction has been rejected

The Twitter joke trial is the clearest indication yet that the world is divided into two sorts of people at the moment. The people who “get it”, and the people who don’t.

The people who get it are those who are living in a world that the internet has created. A new world which would have been unimaginable as little as 15 years ago. Few predicted that this place of cat videos and porn would also allow ordinary people to create content, to engage in citizen journalism, to organise peaceful online protests that bring about actual change, or to do any of the other countless, enriching things that it has made possible.

The people who don’t get it are the people in charge. Politicians (for the most part), judges (for the most part), the policemen who came to Paul Chambers’ place of work and arrested him for posting a piece of frustrated, jokey hyperbole on Twitter. These are the people who, more than anyone, need to understand the modern world. And they simply don’t.

From what I understand, much of the Twitter joke trial has involved trying to communicate to judge and prosecution what Twitter actually is. And if they don’t understand it, then how can they be trusted to make proportionate, reasonable or just decisions about it?

This is the kind of case that would make me refuse jury service. It obliterates my confidence in the judicial system. Why should I let people who don’t “get it” have any power over me or anyone else?

We’re trying to evolve here, and the people who don’t get it are slowing us down. If they can’t keep up, they need to get out of the way.

Graham Linehan blogs at whythatsdelightful.wordpress.com, and tweets at @glinner

From top left: Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, Leyla Yunus, Khadija Ismayilova, Intigam Aliyev and Anar Mammadli – some of the government critics jailed on trumped up charges in Azerbaijan

Social media users have hijacked the hashtag #HelloBaku to draw attention to human rights and free speech violations in Azerbaijan ahead of this summer’s inaugural European Games in the capital Baku.

Baku 2015 organisers launched the hashtag contest on 4 March 2015, as part of a promotional push ahead of the games, which start on 12 June. Social media users were invited to enter by posting a photo or video of themselves holding a sign with #HelloBaku written on it. The winner, set to be announced this week, will be awarded two tickets to the opening ceremony, as well as a night at a luxury hotel and flights.

Post a photo of you saying #HelloBaku to win tickets to @BakuGames2015 opening ceremony! ✈️ http://t.co/2VMRbqux92 pic.twitter.com/CURPEEa0AL

— 2015 European Games (@BakuGames2015) March 20, 2015

But the campaign backfired, as a number of social media users instead used #HelloBaku to highlight Azerbaijan’s poor record on human rights. According to the latest estimates, there are over 100 political prisoners in the country. Since last summer, authorities have been engaged in an unprecedented onslaught against its most prominent critics, jailing investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, pro-democracy activist Rasul Jafarov, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and others on trumped up charges. On 9 April, prosecutors asked for a 9-year sentence for Jafarov, who stands accused of tax evasion and malpractice, among other things.

#HelloBaku hashtag seems to have drawn more attention to Azerbaijan’s record of alleged rights abuses than its hosting of European Games — Thomas Grove (@tggrove) April 4, 2015

#HelloBaku: Free jailed activists and journalists so Index’s @jodieginsberg can say hello to them too pic.twitter.com/dy8q3lzni4

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) March 31, 2015

.@biginbaku What else is on offer in #HelloBaku? Journalists, bloggers in prison, crackdown on government critics. pic.twitter.com/rKx9AwTCPs — Wenzel Michalski (@WenzelMichalski) March 26, 2015

#HelloBaku @amnesty: “No one should be fooled by glitz & glamour…#Azerbaijan is putting on” http://t.co/Ekz1JFGUIO pic.twitter.com/dqTd5wBt68 — Kate Nahapetian (@KN87) March 23, 2015

My friend @Khadija0576 is in prison. Human rights worker Leyla Yunus, Prof Intigam Aliyev are in prison. Give them a ticket out. #HelloBaku — Shabnam (@Peaceweet) March 24, 2015

Must-read for @UNICEF @BP_plc @CocaCola http://t.co/N22wvofeRF #HelloBaku + video with @dinarayunus https://t.co/iZTYgxl79r #Baku2015 — Jan Kooy (@KooyJan) April 7, 2015

#HelloBaku: Big court day today; @rasuljafarov & lawyer Khalid Bagirov in court now and at 15:00 IRFS will be in court #Azerbaijan — Human Rights Houses (@HRHFoundation) April 9, 2015

#HelloBaku: European Olympic Committee Urged to Press #Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Opposition https://t.co/Le6O2s7deg #Baku2015 #EuropeanGames — Ani Wandaryan (@GoldenTent) April 7, 2015

Trial in the case of Intigam Aliyev #Azerbaijan #HelloBaku #RealBaku2015 #SportForRight #FreeIntigam #HelloBaku http://t.co/p1XMyLcve0 — HUMAN RIGHTS (@azhumanrights) April 9, 2015

#HelloBaku, Hello From Prison. #realBaku2015 #Azerbaijan #Baku2015 #freeLeyla #freeKhadija https://t.co/fNDKVEckWI pic.twitter.com/jeSZqezllj — STOPREPRESSIONS (@stoprepressions) April 3, 2015

5 April 2015 #Azerbaijan‘i opposition holds rally. #Baku2015 #HelloBaku #RealBaku2015 #SportForRights #Talanason pic.twitter.com/uWQ4hjNRLB — AXCP PRESS CENTER (@A_X_C_P) April 6, 2015

New sport and rights coalition calls for prisoner releases ahead of #BakuGames #Azerbaijan #HelloBaku http://t.co/24KREfFc2P — Nizami Abdullayev (@NizamiHR) April 9, 2015

Prisoner of conscience Leyla Yunus ill in prison. #Azerbaijan should free her now. #HelloBaku? http://t.co/PY31EFNF6T pic.twitter.com/PpzmJXkvxv — Andrew Stroehlein (@astroehlein) March 24, 2015

#HelloBaku Azerbaijan: release of all prisoners of conscience https://t.co/d1GM0dHQNN #Baku2015 pic.twitter.com/4xG9Y3K58q — Amnesty NL (@amnestynl) March 23, 2015

in Azerbaijan have 101political prisoners !Guys people do not need these Olimpic @BakuGames2015 !The people in terrible condition #HelloBaku — Sevinj NM (@SevinjNM) April 7, 2015

Love this photo, which captures the contrasts of life in #Baku, #Azerbaijan via @MeydanTV #HelloBaku pic.twitter.com/7v5LDz2cxo — Rebecca Vincent (@rebecca_vincent) March 22, 2015

On 30 March, the same day the contest closed, Human Rights Watch researcher Giorgi Gogia, who was set to attend the trial hearing of Aliyev and Jafarov, was blocked from entering Azerbaijan. Traveling from his native Georgia, Gogia does not require a visa to go to Azerbaijan. Despite this, his passport was taken away and he was held at the Heydar Aliyev International Airport in Baku for 31 hours without explanation, before being sent back to Tbilisi.

My account of 31-hour ordeal at #Baku airport. Happy to be home, but sad for jailed rights defenders in #Azerbaijan https://t.co/qmKF9yhiRM — Giorgi Gogia (@Giorgi_Gogia) March 31, 2015

Repression in #Azerbaijan no #AprilFools joke: @HRW‘s @Giorgi_Gogia airport ordeal https://t.co/ww4CBuTEa3 #HelloBaku pic.twitter.com/aihfMV2zSu — Minky Worden (@MinkysHighjinks) April 1, 2015

Will @BakuGames2015 RT this latest on #Azerbaijan‘s crackdown on human rights? http://t.co/swQttNqru1 #HelloBaku pic.twitter.com/vwlVzVzg8J — EmmaDaly (@EmmaDaly) April 1, 2015

Azerbaijan’s authorities, led by President Ilham Aliyvev, have been accused by human rights groups of running an expensive international PR operation to whitewash rights violations, and present the country as a “modern, outward looking state“. According to the Baku European Games Operation Committee (BEGOC), the games will “showcase Azerbaijan as a vibrant and modern European nation of great achievement”.

#HelloBaku MT @GoldenTent: #EuropeanGames aren’t sporting event but expensive propaganda – @eminmilli http://t.co/oW6fQ8BoRa #Azerbaijan — Florian Irminger ✏️ (@FlorianIrminger) April 6, 2015

London-based marketing firm 1000heads, whose clients include Yahoo, Procter & Gamble and Lego, worked with Baku 2015 organisers on #HelloBaku. Index contacted 1000heads to ask whether they were aware of criticisms against Azerbaijan’s human rights record before taking on the job, and their response to the hijacking of the hashtag.

“We were working with BEGOC, the Baku European Games Operation Committee, which is responsible for delivering the event for athletes from the 49 National Olympic Committees of Europe. We are no longer involved,” 1000heads CEO Mike Rowe said in an email.

This article was posted on 8 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

I was retweeted by Caitlin Moran on Wednesday evening (#humblebrag). It was a curious glimpse into the world of internet fame. Suddenly my replies were full of retweets and favourites – hundreds of them.

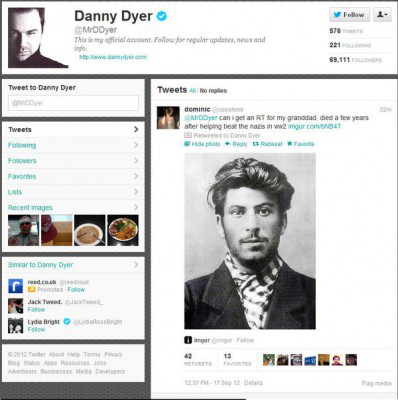

The tweet itself was fairly innocuous; in fact, it was a bit of a cheat. I’d copied someone else’s tweet, adding my own disbelief. And that tweet by someone else was a retweet of a three-year old tweet by well-hard actor Danny Dyer, who had been tricked, quite amusingly, by someone asking for a shout out to his grandad who had helped beat the Nazis, accompanied by a picture of a young Stalin. I’d missed it at the time.

Anyway, on it came throughout the evening, retweets, favourites, questions, statements of the obvious, snark…. It was weird, and unexpected, and kind of exciting. It was like I’d done something really good, rather than just stealing someone else’s old joke. And I was able to track exactly how good it was. I had pulled some kind of killer move and was getting my reward. I was winning the game.

In his 2013 documentary on video games that changed the world, Charlie Brooker, who knows so much about these things, caused a small stir when he suggested that Twitter was in essence, an online multiplayer game. Considering how high-mindedly people like me talk about social media as platforms for change, tools of democratisation and so on, it’s a provocative view to take. But Brooker is right. Twitter users are engaged in a massive game, possibly without end. We measure the success of individual moves (tweets) with retweets and favourites: keep pulling off these successful moves, and we can see our scores go up, in terms of followers accumulated. Not counting the uber famous, who will get a million retweets for the most grudgingly given “I HEART MY FANS; here’s the merchandise page” tweet, most of us are in this game to some extent.

But the description of Twitter as a game has one problem: Twitter can have real-life consequences.

Periodically (well, every time Grand Theft Auto comes out), Keith Vaz or Susan Greenfield or someone will get terribly upset about the ruination caused to young minds or young morals by all this mindless violence. This game lets you steal cars! Run down old ladies! All sorts of unspeakable things! But GTA and other games let you do nothing of the sort: at best, they let you pretend you’re doing these things. In fact, it’s not even that: it lets you control a character, whose character is already somewhat predetermined, in doing some of these things. You’re essentially engaged in a technologically advanced form of improv theatre. Except far more entertaining.

And this is where the Twitter-as-game thing falters: if I threaten to blow up a plane while playing a normal video game, nothing will happen to me. If I do it on Twitter, well…

Last Sunday a 14-year-old Dutch girl called Sarah got in trouble for tweeting that she was a member of Al Qaeda and was about to do “something big” to an American Airlines flight.

According to Dutch news agency BNO, the exchange went as follows:

“Hello my name’s Ibrahim and I’m from Afghanistan. I’m part of Al Qaida and on June 1st I’m gonna do something really big bye,” the girl, identifying herself only as Sarah, said in Sunday’s tweet. Soon after, American Airlines responded in their own tweet: “Sarah, we take these threats very seriously. Your IP address and details will be forwarded to security and the FBI.”

“omfg I was kidding. … I’m so sorry I’m scared now … I was joking and it was my friend not me, take her IP address not mine. … I was kidding pls don’t I’m just a girl pls … and I’m not from Afghanistan,” the girl said in subsequent tweets, later adding: “I’m just a fangirl pls I don’t have evil thoughts and plus I’m a white girl.”

It’s a stupid thing to do, obviously. But Sarah was playing by the rules of the game. She was being provocative, and, in her mind at least, funny. These are things that get you RTs and followers.

But sadly for Sarah, and the rest of us, there comes a point where social media stops being a game and starts being serious business.

We’ve seen this in the UK, of course, with Paul Chambers and the infamous Twitter Joke Trial.

That entire case was a travesty, because no one at any point believed Chambers even meant to behave threateningly. It’s unlikely anyone really believes Sarah meant anything by her tweet either, but in the order of things so far established, directing a comment at an account (at-ing someone, for want of a better phrase), as the Dutch girl did, is worse than simply referring to them, as Chambers did in his tweet about blowing Doncaster’s Robin Hood airport “sky high”.

Where is all this going to end up? I really don’t know. But I can only reiterate the point made many times before that, intriguingly, with the increasing ease of free speech, we’re seeing the rise of an increasing urge to censor; not just in authorities, but in everyday people.

It’s an urge we have to resist.

This article was originally published on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org