Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The full report is available in PDF format

The Republic of Ireland has seen a steady decline in media plurality, according to the authors of a new report.

The recent Report on the Concentration of Media Ownership in Ireland, published on 19 October, concludes that the country has one of the most concentrated media markets, with wealthy media owners possessing the influence to skew the news report for personal gain. According to the report the The authors — Caoilionn Gallagher and Jonathan Price at Doughty Street Chambers, Gavin Booth and Darragh Mackin at KRW Law, and commissioned by Lynn Boylan MEP– drew on a variety of studies to compile the report including research from the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom’s Media Pluralism Monitor (2015). Based on the source material, the report examined how diversity in viewpoints and opinions are reflected in a nation’s media content.

CMPF created a Media Pluralism Monitor to measure whether a country is a “high risk territory” on a scale of 0% to 100%, with “high risk” countries falling at 74% or above. Researchers based in the 19 countries covered by the monitor collect data points that include protection of journalists, number of media outlets, political independence and social inclusiveness among other indicators.

In 2015 Dr. Roderick Flynn, of Dublin City University, generated a report on Ireland for CMPF’s Media Pluralism Monitor which found there was a “medium risk” (54%) of market plurality, and specifically “very high risk” (74%) in relation to the “concentration of media ownership”. Based on Flynn’s research it was concluded that, largely, the media concentration stemmed from businessman Denis O’Brien, founder of Communicorp, owner of a significant minority stake in Independent News and Media and a large portion of the commercial radio sector. The October report called O’Brien’s ownership and influence in media outlets a concern. Additionally, Doughty Street Chambers and KRW Law highlighted the Irish defamation law as a key issue “which threatens news plurality and undermines the media’s ability to perform its watchdog function”.

Though Flynn’s study and the Doughty Street Chambers and KRW Law report clearly point out significant issues, which have been further discussed with organisations such as the National Union of Journalists and the EU Commission, it also proposes ideas for revisions. The report states the “firm view that there must be detailed multi-disciplinary analysis and careful consideration before any steps are taken”. The authors of the report suggest that the Irish should “establish a cross-disciplinary commission of inquiry”, which would “examine the issues closely and make concrete recommendations.” Additionally the authors ask the Council of European Committee of Experts on Media Pluralism and Transparency of Media Ownership to work within the parameters of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), a treaty that “the right to [business] property is heavily caveated under”. Consequently, by utilising the ECHR, the committee could spur a decrease in the media power of business moguls such as Denis O’Brien. Along with further modifications, the study indicates that these alterations are necessary to maintain media plurality in Ireland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1479382383515-ed0923d1-1fb7-1″ taxonomies=”76″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

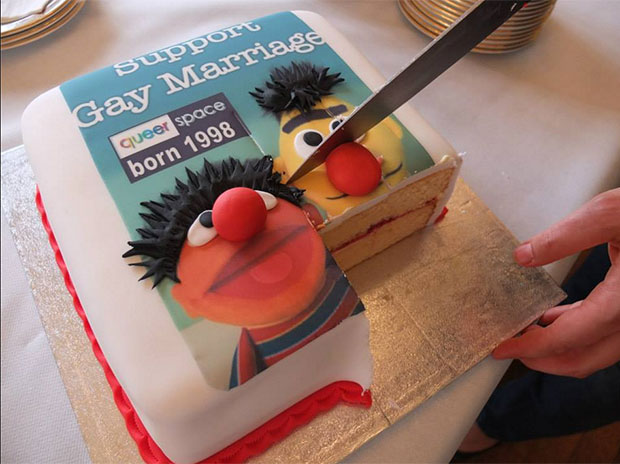

Cake decoration seems like an odd thing to divide a society, but it’s causing a major rift in Northern Ireland.

On Tuesday the Belfast Court of Appeal ruled that the family-owned Ashers bakery discriminated against Gareth Lee, a member of the city’s QueerSpace collective, by refusing to honor his order for a cake decorated with a picture of “Sesame Street” characters Bert and Ernie and a slogan in support of equal marriage. Read the full article

Monument to Veronica Guerin in Dublin Castle gardens. Credit: William Murphy / Flickr

This weekend marks 20 years since the murder of Irish award-winning crime and investigative journalist Veronica Guerin. On 26 June 1996, two masked men on a motorbike pulled up alongside her car at traffic lights on the outskirts of Dublin, opened fire and killed her instantly. Three men were subsequently convicted for their involvement in the murder.

Guerin, who had been working as a freelance journalist for Ireland’s Sunday Independent, made a name for herself investigating and exposing the crimes of senior members of Dublin’s criminal underworld. But such a reputation can be a dangerous thing for an investigative reporter to have. Guerin was subject to a number of attacks and threats, including against the life of her young son Cathal. In 1995 she was shot in her home but survived. Refusing to yield, she continued her work.

“Veronica was a late entrant to journalism; she trained and worked initially in accountancy so she had an instinct for business and understood money,” says Séamus Dooley, Irish Secretary, National Union of Journalists. “That was very useful in studying records and following the money.”

Her death prompted a wave of public anger culminating in the establishment of the Criminal Assets Bureau, followed by more than 150 arrests and a major hunt for organised criminal gangs. “The idea of a designated bureau with sweeping powers to target those with suspicious wealth was a direct response to her murder and caused havoc among those heading criminal gangs,” says Dooley.

Guerin’s death was described by then-Taoiseach John Bruton as a “an attack on democracy”. Unfortunately, this sentiment was echoed earlier this year when current Taoiseach Enda Kenny said: “Journalists and media organisations will not be intimidated by such threats, which have no place in a democratic society.”

The threats he was referring to were made in February 2016 by criminal gangs in Dublin against a number of crime journalists in the city who were reporting on a gangland feud that saw two audacious murders in the space of four days. Police informed Independent News and Media, which owns the Irish Independent newspaper, that the safety of two reporters — a man and a woman — was at risk.

Jimmy Guerin, the brother of Veronica, said at the time: “Successive governments have let down the memory of Veronica … by failing to provide the resources required to beat the gangs.”

So are we back to the way things were two decades ago?

“The situation has been simmering beneath the surface for a while, but the turf wars between the Kinahan and the Hutch families, along with the nature of the violence, is new,” says Dooley. “Gerry Hutch is someone Veronica would have covered in her time, so there is a direct connection with what came before.”

“However, there was this perception that Dublin was a city on lockdown following the killings and journalists are operating under fear,” adds Dooley. “This isn’t bandit country, and there aren’t large numbers of journalists fearful for their lives.”

This shouldn’t mean complacency, adds Dooley, who states that the NUJ has supported a number of journalists at risk in Ireland in recent years.

“One of the problems is that Dublin is a small city, so, naturally, the number of people covering crime is very small,” says Dooley. “Veronica was very well-known to the people she was writing about and so are today’s reporters.”

With crime reporting being such a small part of the market, there is great pressure to deliver stories quicker, which brings problems in itself.

“Today’s journalists are expected to take more risks, and freelancers — as Veronica was — take even greater risks than those in staff jobs,” says Dooley. “While I understand that there is also the commercial element of selling newspapers in order to survive, sensationalising crime coverage in such a high profile way and being overly provocative in the process of selling comes at a price.”

A similar situation exists in Northern Ireland, which remains a difficult place to be a journalist. In September 2001, Martin O’Hagan, a journalist with the Sunday World, became the first journalist to be killed in Northern Ireland since the outbreak of the Troubles in 1969. He was murdered by loyalist paramilitaries as he walked home from a pub in Lurgan, in what was widely believed to be retaliation for his investigations into drug dealing by these same gangs.

His murder remains an isolated case, but recent years have seen a spate of attacks and threats against journalists in the country. In 2014, Irish News reporter Allison Morris was called a “Fenian bastard” and a “Fenian cunt” as she left court by a gang who threatened to cut her throat.

In July the previous year, the NUJ condemned the “upward trend” in attacks on journalists in Northern Ireland after a French photographer was assaulted during rioting in East Belfast. Two months earlier death threats were issued by loyalist paramilitaries against two journalists in the region. Dissident republicans have made similar threats in recent years.

These are not isolated incidents in either the north or south of Ireland.

If we are to learn anything from the death of Veronica Guerin all these years later, says Dooley, it is that “there needs to be greater recognition of the rights of journalists.”

QueerSpace Belfast / Facebook

Last Sunday, as Northern Ireland’s footballers prepared to play Finland in a European Championship qualifier, protesters gathered outside Windsor Park, the team’s Belfast home.

The assembled were members of the Free Presbyterian Church. They were angered by the fact that Northern Ireland were playing on a Sunday – the Sabbath – for the first time ever.

Reverend Raymond Robinson told the Press Association: “Our opposition is to the breaking of observance of the Lord’s day.

“We believe in the Sabbath being kept holy. It seems more and more that the football agenda is being driven by the television companies and not what God says, or what public opinion is.”

Commentator Newton Emerson was, like many, blase about the protest, tweeting “I think these people are harmless enough now to just count towards our wonderful diversity.”

Be that as it may, Christian fundamentalism still plays a huge role in public life in Northern Ireland. While the old demands for Biblical propriety may seem archaic, a new struggle has emerged over what many religious people in the country see as threats to their religious freedom and way of life. And a cake has become the latest flashpoint.

Asher’s bakery is a business run by a family known for its Christian beliefs. It is named after one of the Biblical Twelve Tribes of Israel. Last summer, the bakery was asked to provide a cake by Gareth Lee, a volunteer for LGBT group QueerSpace.

Lee had requested a cake decorated with a picture of Sesame Street’s Bert and Ernie and the slogan “Support Gay Marriage”.

The bakery initially accepted the order, before then informing Lee that it could not fulfil the deal. The case went to Northern Ireland’s Equality Commission, and, between the jigs and reels, is now in the hands of district judge Isobel Brownie, who will rule on Monday whether the Christian bakers engaged in unlawful discrimination by not delivering the pro-same sex marriage cake.

Meanwhile, the “gay cake” case has raised the spectre of a “conscience clause” in equality legislation in Northern Ireland.

The whole situation is, quite frankly, pitiful. One can preach it, validly, both ways: fundamentalist bigots out of touch with the modern world, and inflicting their bigotry on others, or God-fearing, humble folk sticking by their beliefs in the face of an onslaught they didn’t invite.

I can’t help feel sympathetic towards the McArthurs, the family who own the bakery. Karen McArthur told the court that she had initially accepted the order to avoid embarrassment. Colin McArthur said “On that day I didn’t make a clinical decision. I was examining my heart. I was wrestling it over in my heart and in my mind.” He was, apparently, “deeply troubled”. “We discussed how we could stand before God and bake a cake like this promoting a case like this…”

On the other hand, Gareth Lee said he was left feeling like a lesser person after he was told his order would not be fulfilled.

This shouldn’t be down to who was more upset or offended, but then, on what criteria can we judge it? I don’t think it’s necessarily true to say that Lee is entitled to have any message he wants put on any cake by any person. The prosecution, correctly, pointed out that the message was rejected because of the word “gay”. The defence lawyers suggested that a ruling against the McArthurs could lead to a situation where devout Muslims were legally obliged to decorate cakes with images of Muhammad. While “you wouldn’t say that about the Muslims” is a tedious argument, and one deployed increasingly often by Christians, it’s not, in this case, an entirely unreasonable position.

Hardline Christians see homosexuality as a (wrong) choice people make, or a psychological disorder. I recall watching the Reverend Willie McRea, an MP, once, being asked what support he would offer to a constituent who was a victim of homophobia. McRea replied that he would advise the young man not go down that route: basically, the best way to prevent homophobia is to stop being gay.

Meanwhile, Iris Robinson, wife of Democratic Unionist Party leader Peter Robinson, firmly believes that one can be counselled away from homosexuality.

These people are odd, certainly, but they are not fringe characters who can be dismissed as irrelevant to mainstream society in Northern Ireland.

And even if these views were not mainstream, that would not make the fundamentals of the case any different. But it does seem as if the Equality Commission is trying to drag a segment of Northern Irish society kicking and screaming into the secular world.

So who’s right? Who should win? Reader, I am about to break the columnist’s solemn covenant and admit: I don’t fully know. This is not as clear cut a case of discrimination as, say, barring a gay couple from a Bed and Breakfast: if the McArthurs had simply refused to sell a cake to Lee, that would be clear cut. But the cake was loaded, so to speak. Should this tricky case lead to a “conscience clause” in equality legislation, then one can imagine legitimisation of genuinely discriminatory practices.

At the same time, the McArthurs, are wrong, and one’s initial inclination is to side with the gay rights activist against the religious fundamentalists. But that’s the problem with defending freedom of conscience, (and its expression in freedom of speech). Everyone’s conscience is different.

Northern Ireland beat Finland 2-1, by the way. God’s clearly not very troubled by Sunday football.

This column was posted at indexoncensorship.org on April 2, 2015