The unnamed

FEATURING

Hilary Mantel

Author

Valerie Plame Wilson

Former CIA officer

Can Dündar

Journalist

FEATURING

Author

Former CIA officer

Journalist

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

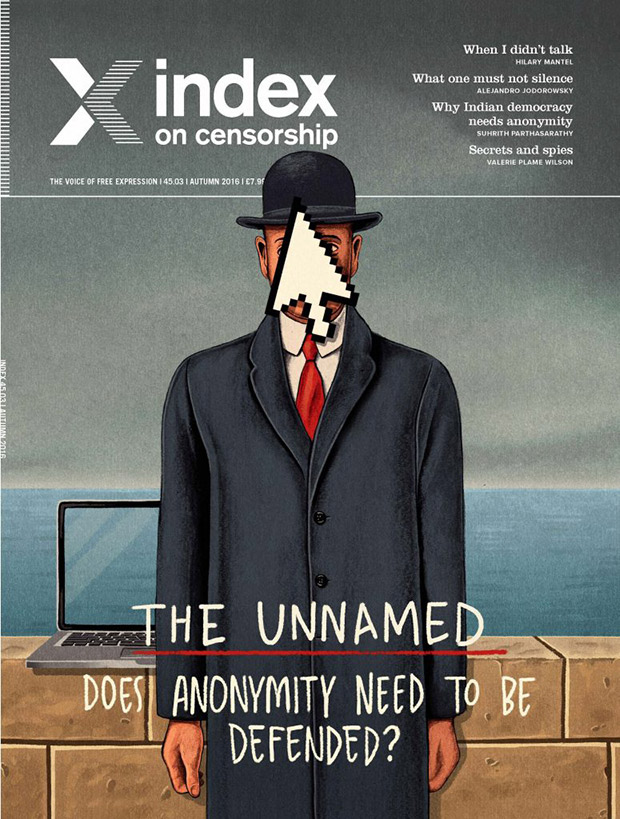

Autumn’s anonymity cover by Ben Jennings

The forthcoming issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers. Contributors include former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson, journalist John Lloyd, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad and philosopher Julian Baggini,

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, illustrated by Molly Crabapple. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov explores how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. There is also poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

You can pre-order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

NGOs from the around the world call for the immediate release of prisoner of conscience Dr. Abduljalil al-Singace on his 300th day of hunger strike. Dr. al-Singace began his hunger strike in March 2015 as a response to police subjecting inmates at the Central Jau Prison to collective punishment, humiliation and torture.

Since 21 March 2015, Dr. al-Singace has foregone food and subsisted on water and IV fluid injections for sustenance. Days later, Jau prison authorities transferred him to the Qalaa hospital, where he is still being kept in a form of solitary confinement.

Dr. al-Singace’s family, who visited him on 7 January, state that the prison administration is controlling his treatment at Qalaa hospital, and has for five months continuously, denied his need for a physical checkup by his hematologist at Salmaniya Medical Complex.

According to Dr. al-Singace’s family, he is not allowed to walk outside. He remains isolated in the Qalaa hospital, and is provided only irregular contact with his family. He is frequently denied basic hygienic items including soap, and is not allowed to interact with other patients in the hospital.

Dr. al-Singace is a member of the Bahrain 13, a group of thirteen peaceful political activists and human rights defenders, including Ebrahim Sharif and Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, sentenced to prison terms for their peaceful role in Bahrain’s Arab Spring protests in 2011.

Dr. al-Singace was first arrested in August 2010 at Bahrain airport. He had just returned from a conference at the British House of Lords regarding human rights in Bahrain. Security forces detained Dr. al-Singace for six months, during which he was tortured, and released him in February 2011 during the height of protests. However, Dr. al-Singace was rearrested on 17 March 2011, after his participation in peaceful pro-democracy protests. In detention, officers blindfolded, handcuffed, and beat Dr. al-Singace in the head with their fists and batons. Officers threatened him and his family with reprisals.

On 22 June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr. al-Singace to life for attempted overthrow of the regime. Since then, he has been imprisoned in the Central Jau Prison, and has only recently received treatment for a nose injury sustained during torture. He has been denied treatment for a similar ear injury also sustained during torture since his incarceration.

In 2015, Dr. al-Singace was awarded the Liu Xiaobo Courage to Write Award by the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, and was named one of Index on Censorship’s 100 “free expression heroes” in 2016. He has long campaigned for an end to torture and political reform, writing on these and other subjects on his blog, Al-Faseela, which remains banned by Bahraini Internet Service Providers. Bahrain has become a dangerous place for those who speak out, with peaceful dissidents at risk of arbitrary arrests, systematic torture and unfair trial.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call on the government of Bahrain to immediately secure the release of Dr. al-Singace and all prisoners of conscience, and to provide all appropriate and necessary medical treatment for Dr. al-Singace.

Signatories:

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Croatian PEN

Danish PEN

English PEN

European Center for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

FIDH, within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Ghanaian PEN

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Italian PEN

Norwegian PEN

PEN America

PEN Bangladesh

PEN Bolivia

PEN Canada

PEN Català

PEN Center Argentina

PEN Center USA

PEN Centre of German Speaking Writers Abroad

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Flander

PEN Germany

PEN International

PEN Netherlands

PEN New Zealand

PEN Québéc

PEN Romania

PEN South Africa

PEN Suisse Romand

Peruvian PEN

Reporters Sans Frontiers (RSF)

San Miguel PEN

Scholars at Risk

Scottish PEN

Serbian PEN

Trieste PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Zambian PEN