14 Feb 2018 | Awards, News, Press Releases

- Judges include Serpentine CEO Yana Peel; BBC journalist Razia Iqbal

- Sixteen courageous individuals and organisations who fight for freedom of expression in every part of the world

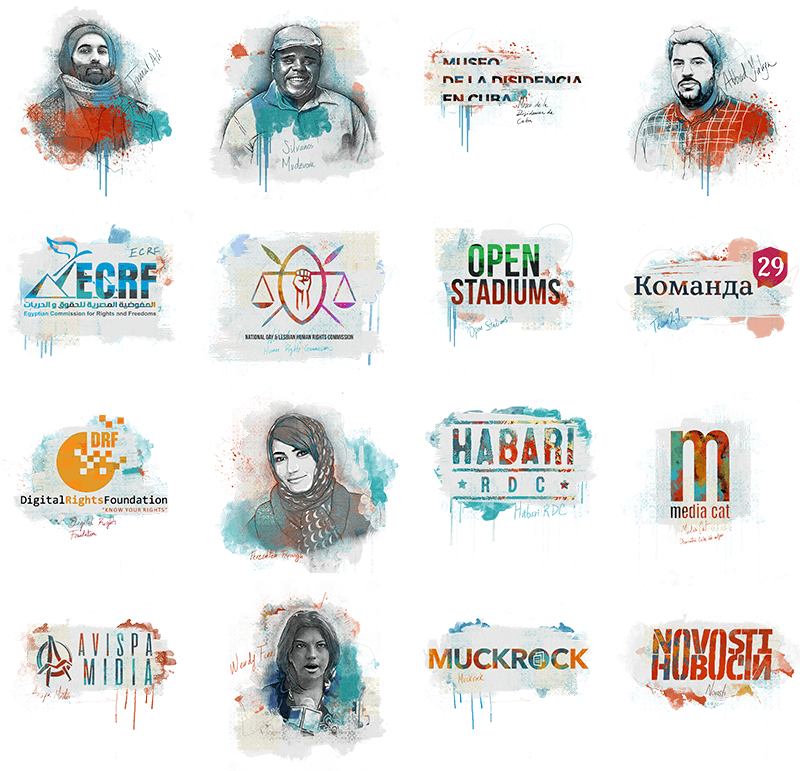

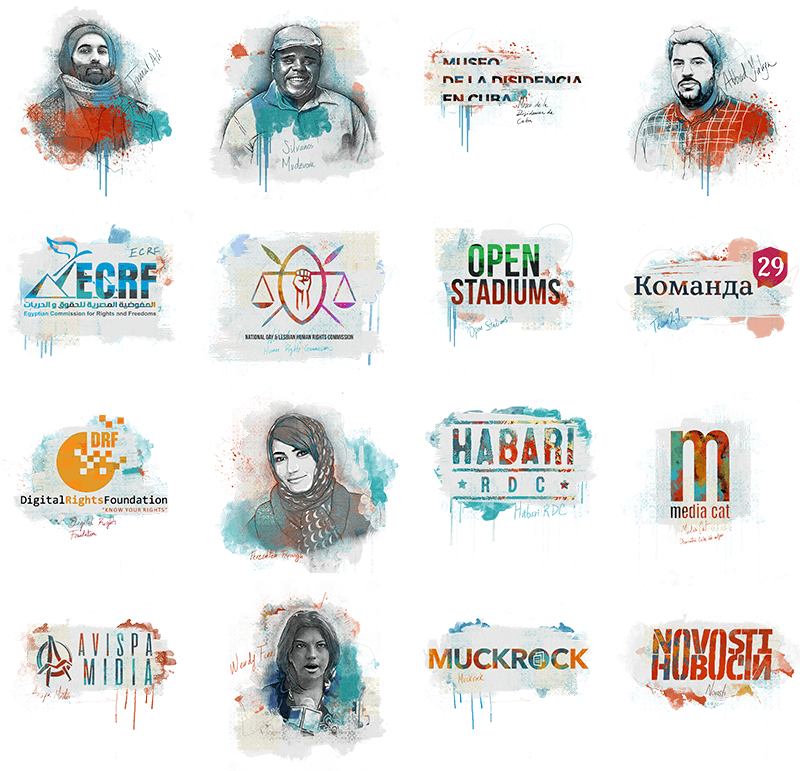

An exiled Azerbaijani rapper who uses his music to challenge his country’s dynastic leadership, a collective of Russian lawyers who seek to uphold the rule of law, an Afghan seeking to economically empower women through computer coding and a Honduran journalist who goes undercover to expose her country’s endemic corruption are among the courageous individuals and organisations shortlisted for the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowships.

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“Free speech is vital in creating a tolerant society. These nominees show us that even a small act can have a major impact. These groups and individuals have faced the harshest penalties for standing up for their beliefs. It’s an honour to recognise them,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards fellowships are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include rapper Jamal Ali who challenged the authoritarian Azerbaijan government in his music – and whose family was targeted as a result; Team 29, an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia; Fereshteh Forough, founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan; Wendy Funes, an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country.

Other nominees include The Museum of Dissidence, a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba; the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, a group proactively challenging LGBTI discrimination through the Kenya’s courts; Mèdia.cat, a Catalan website highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories; Novosti, a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia that deals with a whole range of topics.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 18th year, are BBC reporter Razia Iqbal, CEO of the Serpentine Galleries Yana Peel, founder of Raspberry Pi CEO Eben Upton and Tim Moloney QC, deputy head of Doughty Street Chambers.

Iqbal says: “In my lifetime, there has never been a more critical time to fight for freedom of expression. Whether it is in countries where people are imprisoned or worse, killed, for saying things the state or others, don’t want to hear, it continues to be fought for and demanded. It is a privilege to be associated with the Index on Censorship judging panel.”

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given year-long support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“This award feels like a lifeline. Most of our challenges remain the same, but this recognition and the fellowship has renewed and strengthened our resolve to continue reporting, especially on the bleakest of days. Most importantly, we no longer feel so alone,” 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards Journalism Fellow Zaheena Rasheed said.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Private Internet Access, Edwardian Hotels, Vodafone, media partner VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers and Psiphon. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

- Index on Censorship is a UK-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide.

- More detail about each of the nominees is included below.

- The winners will be announced at a ceremony in London on 19 April.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected].

More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2018.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship nominees 2018

ARTS

Jamal Ali

Azerbaijan

Jamal Ali is an exiled rapper and rock musician with a history of challenging Azerbaijan’s authoritarian regime. Ali was one of many who took to the streets in 2012 to protest spending around the country’s hosting of the Eurovision song contest. Detained and tortured for his role in the protests, he went into exile after his life was threatened. Ali has persisted in releasing music critical of the country’s dynastic leadership. Following the release of one song, Ali’s mother was arrested in a senseless display of aggression. In provoking such a harsh response with a single action, Ali has highlighted the repressive nature of the regime and its ruthless desire to silence all dissent.

Silvanos Mudzvova

Zimbabwe

Playwright and activist Silvanos Mudzvova uses performance to protest against the repressive regime of recently toppled President Robert Mugabe and to agitate for greater democracy and rights for his country’s LGBT community. Mudzvova specialises in performing so-called “hit-and-run” actions in public places to grab the attention of politicians and defy censorship laws, which forbid public performances without police clearance. His activism has seen him be traumatically abducted: taken at gunpoint from his home he was viciously tortured with electric shocks. Nonetheless, Mudzvova has resolved to finish what he’s started and has been vociferous about the recent political change in Zimbabwe.

The Museum of Dissidence

Cuba

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

Abbad Yahya

Palestine

Abbad Yahya is a Palestinian author whose fourth novel, Crime in Ramallah, was banned by the Palestinian Authority in 2017. The book tackles taboo issues such as homosexuality, fanaticism and religious extremism. It provoked a rapid official response and all copies of the book were seized. The public prosecutor issued a summons for questioning against Yahya while the distributor of the novel was arrested and interrogated. Yahya also received threats on social media and copies of the book were burned. Despite this, he has spent the last year giving interviews to international and Arab press and raising awareness of freedom of expression and the lives of young people in the West Bank and Gaza, particularly in relation to their sexuality.

CAMPAIGNING

Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms

Egypt

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms or ECRF is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.

National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission

Kenya

The National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission is the only organisation in Kenya proactively challenging and preventing LGBTI discrimination through the country’s courts. Even though being homosexual isn’t illegal in Kenya, homosexual acts are. Homophobia is commonplace and men who have sex with men can be punished by up to 14 years in prison, and while no specific laws relate to women, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga has said lesbians should also be imprisoned. NGLHRC has had an impact by successfully lobbying MPs to scrap a proposed anti-homosexuality bill and winning agreement from the Kenya Medical Association to stop forced anal examination of clients “even in the guise of discovering crimes.”

Open Stadiums

Iran

The women behind Open Stadiums risk their lives to assert a woman’s right to attend public sporting events in Iran. The campaign that challenges the country’s political and religious regime, and engages women in an issue many human rights activists have previously thought unimportant. Iranian women face many restrictions on using public space. Open Stadiums has generated broad support for their cause in and out of the country. As a result, MPs and people in power are beginning to talk about women’s rights to attend sporting events in a way that would have been taboo before.

Team 29

Russia

Team 29 is an association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech in Russia. It is crucial work in a climate where hundreds of civil society organisations have been forced to close and where increasingly tight restrictions have been placed on public protest and political dissent since mass demonstrations rocked Russia in 2012. Team 29 conducts about 50 court cases annually, many involving accusations of high treason. Aside from litigation, they offer legal guides for activists, advice on what to do when state security comes for you and how to conduct yourself under interrogation.

DIGITAL ACTIVISM

Digital Rights Foundation

Pakistan

In late 2016, the Digital Rights Foundation established a cyber-harassment helpline that supported more than a thousand women in its first year of operation alone. Women make up only about a quarter of the online population in Pakistan but routinely face intense bullying including the use of revenge porn, blackmail, and other kinds of harassment. Often afraid to report how badly they are treated, women react by withdrawing from online spaces. To counter this, DRF’s Cyber Harassment Helpline team includes a qualified psychologist, digital security expert, and trained lawyer, all of whom provide specialised assistance.

Fereshteh Forough

Afghanistan

Fereshteh Forough is the founder and executive director of Code to Inspire, a coding school for girls in Afghanistan. Founded in 2015, this innovative project helps women and girls learn computer programming with the aim of tapping into commercial opportunities online and fostering economic independence in a country that remains a highly patriarchal and conservative society. Forough believes that with programming skills, an internet connection and using bitcoin for currency, Afghan women can not only create wealth but challenge gender roles and gain independence.

Habari RDC

Congo

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.

Mèdia.cat

Spain

Mèdia.cat is a Catalan website devoted to highlighting media freedom violations and investigating under-reported or censored stories. Unique in Spain, it was a particularly significant player in 2017 when the heightened atmosphere in Catalonia over the disputed independence referendum brought issues of censorship and the impartiality of news under the spotlight. The website provides an online platform that catalogues systematically, publicly and in real time censorship perpetrated in the region. Its map on censorship offers a way for journalists to report on abuses they have personally suffered.

JOURNALISM

Avispa Midia

Mexico

Avispa Midia is an independent online magazine that prides itself on its daring use of multimedia techniques to bring alive the political, economic and social worlds of Mexico and Latin America. It specialises in investigations into organised criminal gangs and the paramilitaries behind mining mega-projects, hydroelectric dams and the wind and oil industry. Many of Avispa’s reports in the last 12 months have been focused on Mexico and Central America, where the media group has helped indigenous and marginalised communities report on their own stories by helping them learn to do audio and video editing. In the future, Avispa wants to create a multimedia journalism school to help indigenous and young people inform the world what is happening in their region, and break the stranglehold of the state and large corporations on the media.

Wendy Funes

Honduras

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.

MuckRock

United States

MuckRock is a non-profit news site used by journalists, activists and members of the public to request and share US government documents in pursuit of more transparency. MuckRock has shed light on government surveillance, censorship and police militarisation among other issues. MuckRock produces its own reporting, and helps others learn more about requesting information. Last year the site produced a Freedom of Information Act 4 Kidz lesson plan to help educators to start discussions about government transparency. Since then, they have expanded their reach to Canada. The organisation hopes to continue increasing their impact by putting transparency tools in the hands of journalists, researchers and ordinary citizens.

Novosti

Croatia

Novosti is a weekly Serbian-language magazine in Croatia. Although fully funded as a Serb minority publication by the Serbian National Council, it deals with a whole range of topics, not only those directly related to the minority status of Croatian Serbs. In the past year, the outlet’s journalists have faced attacks and death threats mainly from the ultra-conservative far-right. For its reporting, the staff of Novosti have been met with protest under the windows of the magazine’s offices shouting fascist slogans and anti-Serbian insults, and told they would end up killed like Charlie Hebdo journalists. Despite the pressure, the weekly persists in writing the truth and defending freedom of expression.

18 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Las violentas represalias que están sufriendo los reporteros que cubren la persecución de los homosexuales en Chechenia pone de relieve los peligros de sacar la verdad a la luz en un estado corrupto. Un periodista checheno habla de las dificultades a las que se enfrenta”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Manifestantes en Toronto (Canadá) marchan para concienciar sobre la situación de las personas LGTB en Chechenia, JasonParis/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Una sola ley gobierna la labor de los periodistas de Chechenia: todos somos parte del servicio de prensa de Ramzan Kadyrov. Desde que Kadyrov llegó al poder en 2007 como jefe de la república, los medios de comunicación se han convertido en su herramienta personal de propaganda. Una vez casi me quedé sin trabajo por utilizar, para un reportaje, metraje en el que salía Alu Aljanov, expresidente de la república y predecesor de Kadyrov. Aljanov es un político decente, pero a Kadyrov no le gusta. Por eso no se puede mencionar su nombre. En otra ocasión, grabé una entrevista con un hombre al que las autoridades chechenas habían torturado. Cuando salió la entrevista a la luz, el hombre tuvo que huir del país para permanecer a salvo. Sigo creyendo es mi culpa.

Los periodistas de aquí y ahora saben lo que pueden y no pueden escribir si quieren mantenerse sanos y salvos. Desgraciadamente, lo que pueden escribir no es mucho. La principal fuente de noticias de cualquier publicación son Kadyrov, su familia y sus parientes. No hay prácticamente una sola historia emitida por los medios chechenos que no nombre a Kadyrov. Tal vez haga referencia al propio jefe de Chechenia; a su padre, asesinado en 2004; a su madre, que dirige una fundación benéfica, o a su mujer e hijos. Así funciona con las noticias de política y hasta con los deportes. Por ejemplo, puede salir un titular diciendo que Kadyrov ha visitado el ensayo de una compañía de danza, ha elogiado a los artistas o le ha entregado al solista las llaves de un coche o incluso de un piso. Otro dirá que Kadyrov se ha pasado por el torneo anual de artes marciales mixtas en Grozny, o mostrará a Kadyrov visitando un hospital y repartiendo sobres de dinero a los pacientes. El único momento de las noticias en el que el jefe de Chechenia no sale nombrado es en el pronóstico meteorológico.

La televisión se utiliza no solo como propaganda sino también como instrumento de intimidación. Las historias que parecen atraer más atención muestran a personas disculpándose ante Kadyrov por haberse quejado de las autoridades. El asunto funciona de la siguiente manera: en las redes sociales, alguien critica a las autoridades y habla de la corrupción, los salarios retenidos o algún secuestro. Las autoridades lo ven, encuentran a su autor y le dan una paliza o lo amenazan, colocan una cámara y lo obligan a disculparse.

Otro ejemplo: cuando Kadyrov empezó a usar Instagram, los chechenos entendieron su presencia en esta red social como una oportunidad de dirigirse a él directamente. Al ver que regalaba pisos, coches y cosas caras a gente distinguida, los ciudadanos empezaron a hablarle de problemas reales, como no tener un techo, tener un hijo enfermo, estar en el paro o cobrar un sueldo ridículamente bajo. Un equipo especial contactaba con el autor de cada petición, acudía a la dirección correspondiente e investigaba la situación. A primera vista, todo muy humanitario; pero, en realidad, el equipo había sido creado para proteger a Kadyrov de los problemas de quienes le hacían peticiones. A menudo la «verificación» terminaba siendo una noticia emitida por televisión en la que denunciaban que la persona en cuestión era un vago o un impostor.

En Chechenia también hay un ejército de trolls de internet. La organización está ubicada en un edificio del complejo de las Torres Grozny-City. Tiene empleadas a una docena de personas que monitorizan constantemente los medios chechenos y rusos y ponen comentarios sobre cualquier cosa que tenga que ver con Kadyrov y con Chechenia. Si es una buena noticia, los empleados de la organización la confirman. Si es mala, la niegan. En una ocasión, un «comentario» escrito por un tal Nikolai de Arjangelsk decía: «Volví ayer de Chechenia. No hay ningún secuestro. Todo el mundo quiere a Kadyrov. Grozny es la ciudad más segura del mundo.»

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Los empleados cobran grandes sumas por su trabajo como trolls. Algunos trabajadores de los medios de comunicación también reciben primas si suben buenas noticias sobre Chechenia a las redes sociales.

Hay medios de comunicación independientes, de Rusia y otros países, que operan en Chechenia, pero también el suyo es un trabajo difícil. Kadyrov dice mucho que los medios de comunicación como Ejo Moskvy, Novaya Gazeta, RBC, Dozhd de Rusia y Meduza de Letonia son traicioneros, hostiles y solo buscan la ruina del país. Por ejemplo, cuando Novaya Gazeta publicó en marzo una serie de artículos de investigación en los que informaban de que estaban atrapando a hombres sospechosos de homosexualidad y torturándolos en prisiones secretas, la historia fue tachada de falsa. Alvi Karimov, portavoz de Kadyrov, describió el reportaje de Novaya Gazeta como “puras mentiras” en una entrevista con la agencia de prensa Interfax, financiada por el estado ruso, en la que decía que no había gais en Chechenia a los que perseguir.

El descrédito no es la única amenaza: los reporteros corren verdadero peligro. Los periodistas de estas publicaciones están sometidos a vigilancia e intimidaciones constantes. A veces los matan. En el último par de décadas, dos periodistas de Novaya Gazeta han sido asesinados mientras cubrían noticias de Chechenia, y el reportero que trabajaba en los casos sobre homosexualidad ha recibido amenazas. En una reunión de unos 15.000 hombres el pasado 3 de abril, Adam Shahidov, consejero de Kadyrov, llamó a los periodistas de Novaya Gazeta «enemigos de nuestra fe y nuestra patria», y prometió «venganza», según denunció el Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas.

Por otro lado, están las dificultades de encontrar gente a la que entrevistar. La gente normal tiene demasiado miedo de hablar con periodistas y los cargos públicos simplemente se niegan a hacerlo. Estos medios de comunicación no pueden contar con corresponsales anónimos en Chechenia porque es casi imposible permanecer en el anonimato. Chechenia es pequeña; todo el mundo se conoce. Los periodistas pueden ocultar su nombre, pero si quieren realizar una labor periodística normal, necesitan entrevistar a gente, dar detalles, describir lo sucedido. Es muy fácil usar esos detalles para entender acerca de qué y de quién se ha escrito el artículo en cuestión. Sabiendo de lo que son capaces las autoridades chechenas en lo que respecta a aplastar la disidencia, nadie quiere exponer alguien solo porque acceda a que lo entrevisten.

Hasta la prensa extranjera sufre. Hasta hace poco estaba bien representada, y los periodistas venían y realizaban entrevistas a menudo. La gente se sentía más cómoda al hablar con ellos, quizá porque los artículos se publicaban en idiomas extranjeros y raras veces se traducían. Pero la situación cambió drásticamente en marzo de 2016, cuando un grupo de periodistas que viajaban con activistas pro derechos humanos sufrieron palizas y graves lesiones en la república vecina de Ingushetia. Alguien prendió fuego a su vehículo y tuvieron que ser hospitalizados. Nadie dudó por un momento que los atacantes habían actuado por orden de las autoridades chechenas. Tras el incidente, pocos periodistas extranjeros se han arriesgado a venir. Sin ellos, la esperanza de poder ofrecer información veraz sobre lo que está ocurriendo en Chechenia es aún más escasa.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

El autor de este artículo es originario de Chechenia y lleva más de diez años trabajado en medios del país. Ha preferido permanecer anónimo por razones de seguridad.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en verano de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 years on” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Nov 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Protesters call for freedom for Nabeel Rajab outside the Bahraini embassy in London.

Nabeel Rajab’s sentence to two years in prison for speaking to journalists was upheld on 22 November 2017 by a Bahraini appeals court at the conclusion of a long-running, unfair trial.

Rajab will serve his sentence at notorious Jau Prison until December 2018, by which time he will have actually spent two and a half years in prison. He faces up to 15 years in prison in a second case related to his comments on Twitter, with the next hearing on 31 December. Index on Censorship and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) condemns Rajab’s imprisonment, which is a reprisal against his work as a human rights defender, and calls for his immediate and unconditional release.

Rajab was sentenced in absentia on 10 July 2017 on charges of “publishing and broadcasting fake news that undermines the prestige of the state” under article 134 of Bahrain’s Penal Code. This is in relation to statements he has made to media that:

-

International Journalists and researchers are barred from entering the country

-

The courts lack independence and controlled by the government. Use judiciary as a tool to crush dissidents.

-

Foreign mercenaries are employed in the security forces to repress citizens

-

Torture is systematic in Bahrain.

In the last appeal court hearing on 8 November, the judge refused to allow the defence’s evidence, which included testimonies of high-profile journalists and researchers who had been banned from entering Bahrain.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy, BIRD: “This is a slap in the face of free expression and tragically proves Nabeel’s point that the justice system is corrupt. Bahrain’s rulers are fearful of the truth and have lashed out against it once again. This Bahraini repression has been enabled by their western allies in the US and UK.”

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship: “This is an outrageous decision. Nabeel has committed no crime. Bahrain needs to end this injustice and its harassment of Nabeel.”

The Bahraini courts have failed to provide Rajab, the president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), a fair trial at every turn. He has been prosecuted for his expression, as protected under article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. During his hospitalisation earlier this year, multiple court hearings were held in Rajab’s absence, including his sentencing in July.

Rajab had a separate hearing on 19 November 2017 in a concurrent case relating to his tweets about torture in Bahrain’s notorious Jau Prison and the Saudi-led coalition’s war in Yemen, for which he faces up to 15 additional years in prison. The court heard a prosecution witness, who had already appeared in a previous hearing last year, and who was not able to provide any evidence against Rajab. The trial was adjourned to 31 December 2017, when the security officer who confiscated Rajab’s electronic devices for another case will be brought as a prosecution witness. The next court hearing will be the eighteenth since the trial began.

Rajab also has been charged with “spreading false news” in relation to a letter he wrote to the New York Times in September 2016. A new set of charges were brought against Rajab in September 2017 in relation to social media posts made in January 2017, when he was already in detention and without internet access.

The human rights defender was transferred to Jau Prison on 25 October 2017, having been hospitalised the previous six months, since April, after a serious deterioration of his health resulting from the authorities’ denial of adequate medical care and unhygienic conditions of detention.

Rajab was subjected to humiliating treatment on arrival at the prison, when guards immediately searched him in a degrading manner and shaved his hair by force. Prison authorities have singled him out by confiscating his books, toiletries and clothes, and raiding his cell at night. Rajab is isolated from other prisoners convicted for speech-related crimes and is instead detained in a three-by-three meter cell with five inmates. Prison officers have threatened him with punishment if he speaks with other inmates, and he is not allowed out of his cell for more than one hour a day.

One of Rajab’s outstanding charges is that he spoke out about the degrading treatment in Jau Prison.The evidence he and BCHR gathered proving torture in the prison was exposed in a joint-NGO report, Inside Jau, in 2015. Human Rights Watch also reported on the same incidents of torture.

The upholding of the sentence means Rajab will be imprisoned at least until December 2018, by which time he will have spent 30 months in prison. This itself reflects the unfair court procedures: Rajab was first arrested in June 2016 and charged with spreading fake news in media interviews. However, the prosecution did not begin investigating his charges until six months into his detention, in December 2016.

International Positions

The UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office has avoided expressing concern over Nabeel Rajab’s sentencing in its answers to four parliamentary questions since July. In their latest statement, they stated: “We continue to closely monitor the case of Nabeel Rajab and have frequently raised it with the Bahraini Government at the highest levels.”

25 British MPs have condemned the sentence.

Following Rajab’s sentencing on 10 July, the United States, European Union and Norway all called for Rajab’s release. Germany deplored his sentence. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ office called for his unconditional release.

In September 2017, the UN condemned the increasing number of Bahraini human rights defenders facing reprisals, naming nine affected individuals, Rajab among them. The UN Committee Against Torture has called for Rajab’s release.

Yesterday, fifteen international and local NGOs wrote to states including the UK, US, EU, Norway, Germany, France, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland and Canada urging them to call for Nabeel Rajab’s immediate and unconditional release. Their voices were joined by protesters in London. In Washington D.C., a petition signed by 15,000 people calling for Rajab’s release was delivered to the Bahrain embassy.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1511346172721-094fe208-2d84-9″ taxonomies=”716, 3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Nov 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Fifteen rights groups have written to 11 states and the European Union on 21 November 2017 calling for action ahead of the conclusion of Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab’s appeal against his two-year sentence for stating that Bahrain bars reporters and human rights workers from entry into the country.

In the letters, which are addressed to the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union, as well as Germany, Ireland, France, Sweden, Italy, Denmark, Switzerland, Norway and Canada, the rights groups ask the states “to urgently raise, both publicly and privately, the case of Nabeel Rajab, one of the Gulf’s most prominent human rights defenders.” The letter further urges governments to support Rajab “by condemning his sentencing and calling for his immediate and unconditional release, and for all outstanding charges against him to be dropped.”

On 22 November 2017 Mr Rajab is expecting the conclusion of his appeal against a two-year prison sentence. Rajab was sentenced on 10 July 2017 on charges of “publishing and broadcasting fake news that undermines the prestige of the state” under article 134 of Bahrain’s Penal Code, in relation to his statement to journalists that the Bahraini government bars reporters and human rights workers from entering the country. In a previous appeal court hearing earlier this month, the judge refused to allow the defence’s evidence, including testimonies of journalists and researchers who had been banned from entering Bahrain.

The human rights defender, who is President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), has been detained since his arrest on 13 June 2016. He was held largely in solitary confinement in the first nine months of his detention, violating the UN Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures (Tokyo Rules).

Rajab faces up to a further 15 years in prison on a second set of charges related to comments he made on Twitter criticising the Saudi-led war in Yemen and exposing torture in Bahrain. His 18th court hearing will be held on 31 December 2017. In September, the Public Prosecution brought new charges against related to social media posts made while he was already in detention; he has also been charged with “spreading false news” in relation to his letter from a Bahraini jail published in the New York Times.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

“The ongoing judicial harassment of Nabeel Rajab is a gross injustice. Nabeel is a man of peace who seeks democratic reforms for his country. His persecution for expressing his opinions — something taken for granted in many nations — must not stand. We call on Bahrain to recognise international human rights norms by releasing Nabeel and ending its prosecution of him.” — Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rajab was transferred to Jau Prison on 25 October 2017. He was subjected to humiliating treatment on arrival, when guards immediately searched him in a degrading manner and shaved his hair by force. Prison authorities have singled him out by confiscating his books, toiletries and clothes, and raiding his cell at night. Rajab is isolated from other prisoners convicted for speech-related crimes and is instead detained in a three-by-three metre cell with five inmates.

Campaigners today protested outside the Bahrain embassy in London to call on the Bahraini regime to release Nabeel Rajab and end reprisal attacks against the family of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, a prominent UK-based human rights campaigner living in exile from Bahrain, who is Director of Advocacy at the London-based Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy, Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy: “Nabeel Rajab has been imprisoned for exposing injustice in Bahrain. Three of my own family members have been imprisoned and tortured for my human rights campaigning. The Bahraini government pursues a pattern of revenge tactics against human rights defenders, but we will not rest until they are freed. If the UK government cares for the rights of Bahraini people, then it must tell its repressive ally that this violent campaign to silence us is unacceptable.”

The 15 rights groups are:

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

English PEN

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights

FIDH within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Front Line Defenders

Global Legal Action Network

Gulf Centre for Human Rights

IFEX

Index on Censorship

International Service for Human Rights

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

World Organisation Against Torture within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”81222″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/11/letter-drop-all-charges-against-nabeel-rajab/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]