26 Jan 2015

2014 Digital Activism Award

Voting has now closed. The winner will be announced 20 March

Click a pin to read nominee information

Edward Snowden

Whistleblower

USA

National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked thousands of documents detailing US government surveillance to the press, igniting a global debate on the ways authorities can and do currently watch citizen’s communications.

•BBC News – Profile: Edward Snowden

•Time Magazine – Edward Snowden, The Dark Prophet

Award Winner Shubhranshu Choudhary

Journalist

India

Journalist Shubhranshu Choudhary is the brains behind CGNET SWARA (Voice of Chhattisgarh) a mobile-phone service that allows citizens to upload and listen to hyper-local reports in their local language, thus circumventing India’s strict radio licencing and creatively providing an outlet for overlooked people on the wrong side of the digital divide.

•The Hindu Magazine – The New Jungle Drums

•BBC News – Giving a voice to India’s villagers

22 Dec 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine, News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

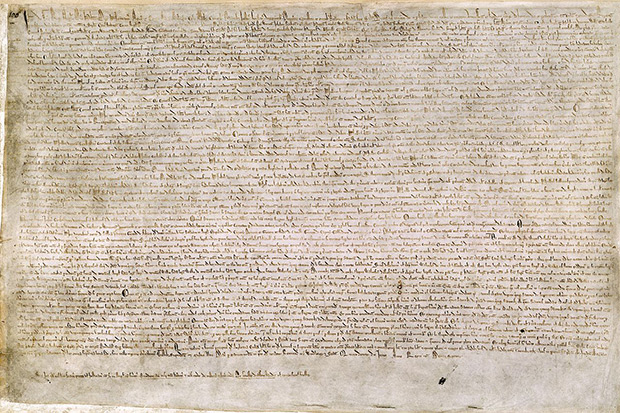

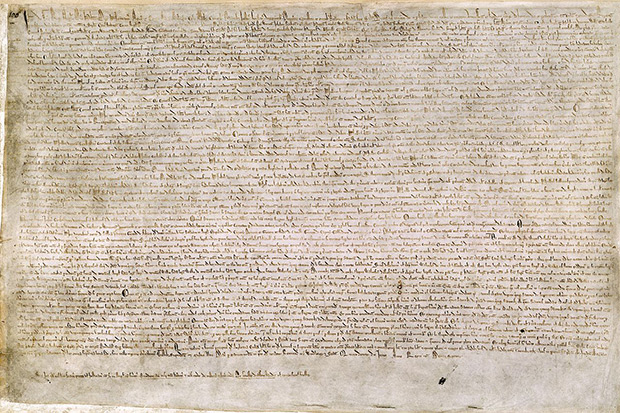

2015 marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. Index on Censorship magazine’s winter issue has a special report that examines all ways in which the document affected modern freedoms. Here John Crace kicks us off with a tongue-in-cheek trip through history

Call it a free for all. Call it an innate sense of fair play. Call it what you will, but the English had always had a way of making their feelings known to a monarch who got a bit above himself by hitting the country for too much money in taxes or losing overseas military campaigns or both. They rebelled. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t but it was the closest medieval England had to due process. Then came John, a king every bit as unloved – if not more so – as any of his predecessors; a ruler who had gone back on many of his promises and was doing his best to lose all England’s French possessions and all of a sudden the barons had a problem. There wasn’t any obvious candidate to replace him.

So instead of deposing him, they took him on by limiting his powers.

Kings never have much liked being told what to do and John was no exception. If he could have got out of cutting a deal with the barons he would have done. But even he understood that impoverishing the people he relied on to keep him in power hadn’t been the cleverest of moves, and so he reluctantly agreed to take part in the negotiations that led to the sealing of The articles of the Barons – later known as Magna Carta – at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. Which isn’t to say he didn’t kick and scream his way through them before agreeing to the 61 demands which were the bare minimum for his remaining in power. He did, though, keep his fingers cunningly crossed when the seal was being applied. As soon as the barons had left London, King John announced — with the Pope’s blessing — that he was having no more to do with it. The barons were outraged and went into open rebellion, though dysentery got to King John before they did and he died the following year. Don’t shit with the people, or the people shit with you. Or something like that.

With the original Magna Carta having lasted barely three months, there were some who reckoned they could have saved themselves a lot of time and effort by topping King John rather than negotiating with him. But wiser – or perhaps, more peaceful – counsel prevailed and its spirit has endured through various subsequent mutations – most notably the 1216 Charter, The Great Charter of 1225 and the Confirmation of Charters of 1297 and has widely come to be seen as the foundation stone of constitutional law, both in England and many countries around the world. It was the first time limitations had been formally placed on a monarch’s power and the rights of citizens to the due process of law and trial by jury had been affirmed. Well, not quite all citizens. When the various charters talked of the rights of Freemen, it didn’t mean everyone; far from it. Freemen just meant that small class of people, below the barons, who weren’t tied to land as serfs. The Brits have never liked to rush things. They like their revolutions to be orderly. The underclass would just have to wait.

Magna Carta and its derivative charters were never quite the symbols of enlightened noblesse oblige they are often held to be. The noblemen didn’t sit around earnestly thinking about how they could turn England into a communal paradise. What was the point of having fought and back-stabbed your way to the top only to give power away to the undeserving? The charters were matters of political expedience. The nobles needed the Freemen on their side in their face-off with the king and an extension of their rights was the bargaining chip to secure it. Benevolence never really entered the equation. Nor was Magna Carta ever really a legal constitutional framework. Even if King John hadn’t decided to ignore it within months, it would still have been virtually unenforceable as it had no statutory authority. It was more wish-list than law.

Ironically, though, it is Magna Carta’s weaknesses that have turned out to have guaranteed its survival. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has become the symbol of freedom rather than its guarantor as different generations have cherry-picked its clauses and interpreted them in their own way. While wars and poverty might have been the prime catalyst for the Peasant’s Revolt against King Richard II in 1381, it was Magna Carta to which the rebellion looked for its intellectual legitimacy. The Freemen were now seen to be free men; constitutional rights were no longer seen as residing in the few. The King and his court were outraged that the peasants had made such an elementary mistake as to mistake the implied capital F in Freemen for a small f and the leaders were executed for their illiteracy as much as their impudence.

Bit by bit, starting in 1829 with the section dealing with offences against a person, the clauses of Magna Carta were repealed such that by 1960 only three still survived. Some, such as those concerning “scutage” — a tax that allowed knights to buy out of military service — and fish weirs, had become outdated; others had already been superseded by later statutes. Two of those that remained related to the privileges of both the Church of England and the City of London — a telling insight into the priorities of the establishment. Those who still wonder, following the global financial collapse of 2008, why the bankers were allowed to get away with making up the rules to suit themselves need look no further than Magna Carta. The bankers had been used to getting away with it for the best of 800 years. You win some you lose some.

The survival of clause 39 of the original Magna Carta has been rather more significant for the rest of us. “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.” Or in layman’s terms, due process: the legal requirement of the state to recognise and respect all the legal rights of the individual. The guarantee of justice, fairness and liberty that not only underpins – well, most of the time – the UK’s constitutional framework, but those of many other countries as well.

Britain has no written constitution. Not because parliament has been too lazy to get round to drawing one up, but because one is already assumed to be in the lifeblood of every one living in Britain. Queen Mary may have had “Calais” written on her heart, but the rest of us all have “Magna Carta” inscribed there. It can be found on the inside of the left ventricle, for those of you who are interested in detail. Other countries haven’t been so trusting in the genetic inheritance of feudal England and have insisted on getting their constitutions down in non-fugitive ink.

That Magna Carta has also been the lodestone for the constitutions of so many other countries, most notably the USA, is less a sign of the global reach of democratic principles – much as that might resonate with romantic ideals of justice — than of the spread of British people and British imperial power. After the Mayflower arrived in what became the USA from Plymouth in 1620, the first settlers’ only reference point for the establishment of civil society was Magna Carta. The settlers had a lot of other things on their minds in the early years — most notably their own survival and the share price of British American Tobacco — and they hadn’t got time to dream up their own bespoke constitution. If they had, they might have come up with something that abolished slavery and gave equal rights to black people sometime before the 1960s. So they settled for an off-thepeg version of Magna Carta, with various US amendments. And some poor spelling. In 1687 William Penn published the first version of Magna Carta to be printed in America. By the time the fifth amendment — part of the bill of rights – was ratified four years after the original US constitution in 1791, Magna Carta had been enshrined in American law with “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

The fact that the American idea of Magna Carta was not one that would necessarily have been recognised in Britain was neither here nor there. For the Americans, the notion of the rights of a people to govern themselves was more than something that had been fought for over many centuries – a gradual taking back of power from an absolute ruler — that had been ratified on paper. They were fundamental rights that pre-existed any country and transcended national borders. And even if there was no one left alive on Earth, these rights would remain. They might as well have been handed down by God, though it’s probably just as well Adam hadn’t read the sections on the right to defend himself and bear arms. If he had shot the serpent, the whole history of the world might have been very different. As it is, when the Americans took on the British in the War of Independence, they weren’t fighting against a colonial overlord so much as for their basic rights to freedom.

The distinction is a subtle but important one. For though the more recent constitutions of former British colonies, such as Australia, India, Canada and New Zealand, more closely reflected the way Magna Carta was understood back in the mothership, those interpretations of it were still very much a product of their time. As a historical document, Magna Carta remains fixed in the 13th century: a practical solution to the problem of an iffy king. But as a concept it is a shifting, timeless expression of the democratic ideal. It can mean and explain anything. Up to and including that Britain always knows best.

Yet the appeal of Magna Carta endures and it remains the gold standard for democracy in any debate. Whatever side of it you happen to be on. British eurosceptics argue that the UK’s continuing membership of the European Union threatens the very parchment on which it was written; that Britain is being turned into a serf by a European despot. Pro Europeans argue that the EU does more than just enshrine the ideals of Magna Carta, it turns the most threatened elements of it into law.

Eight hundred years on, Magna Carta remains a moving target. Something to be aspired to but never truly attained. A highly combustible compound of idealism and pragmatism. Somehow, though, you can’t help feeling that King John and the feudal barons would have understood that. And approved.

This article is from the Winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine as 1215 and all that.

This article was originally posted on Dec 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Oct 2014 | About Index, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Statements

The undersigned 40 organisations call on the international community to publicly condemn the ongoing crackdown on human rights defenders, who face harassment, imprisonment, and forced exile for peacefully exercising their internationally recognised rights to freedom of expression and assembly. With parliamentary elections in Bahrain scheduled for 22 November, the international community must impress upon the government of Bahrain the importance of releasing peaceful human rights defenders as a precursor for free and fair elections.

Attacks against human rights defenders and free expression by the Bahraini government have not only increased in frequency and severity, but have enjoyed public support from the ruling elite. On 3 September 2014, King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa said he will fight “wrongful use” of social media by legal means. He indicated that “there are those who attempt to exploit social media networks to publish negative thoughts, and to cause breakdown in society, under the pretext of freedom of expression or human rights.” Prior to that, the Prime Minister warned that social media users would be targeted.

The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR) documented 16 cases where individuals were imprisoned in 2014 for statements posted on social media platforms, particularly on Twitter and Instagram. In October alone, some of Bahrain’s most prominent human rights defenders, including Nabeel Rajab, Zainab Al-Khawaja and Ghada Jamsheer, face sentencing on criminal charges related to free expression that carry years-long imprisonment.

Nabeel Rajab, President of the BCHR, Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), and Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), was arrested on 1 October 2014 and charged with insulting the Ministry of Interior and the Bahrain Defence Forces on Twitter. Rajab was arrested the day after he returned from an advocacy tour in Europe, where he spoke about human rights abuses in Bahrain at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, and visited foreign ministries throughout Europe.

On 19 October, the Lower Criminal Court postponed ruling on Rajab’s case until 29 October and denied bail. Rajab’s family was banned from attending the proceedings. Under Article 216 of the Bahraini Penal Code, Rajab could face up to three years in prison. We believe that Rajab’s detention and criminal case are in reprisal for his international advocacy and that the Bahraini authorities are abusing the judicial system to silence Rajab. More than 100 civil society organisations have called for Rajab’s immediate and unconditional release, while the United Nations called his detention “chilling” and argued that it sends a “disturbing message.” The United States and Norway called for the government to drop the charges against Rajab, and France called on Bahrain to respect freedom of expression and facilitate free public debate.

Zainab Al-Khawaja, who is over eight months pregnant, remains in detention since 14 October on charges of insulting the King. These charges relate to two incidents, one in 2012 and another during a court appearance earlier this month, where she tore a photo of the King. On 21 October, the Court adjourned her case until 30 October and continued her detention.

Zainab Al-Khawaja is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence in prison, following a grossly unfair trial, for calling for political reforms in Bahrain. Zainab Al-Khawaja has been subjected to continuous judicial harassment, imprisoned for most of last year and prosecuted on many occasions. Three additional trumped up charges were brought against her when she attempted to visit her father at Jaw Prison in August 2014 when he was on hunger strike. The charges are related to “entering a restricted area”, “not cooperating with police orders” and “verbal assault”.

Zainab’s sister, Maryam Al-Khawaja, was also targeted by the Bahraini government recently. The Co-Director of the GCHR is due in court on 5 November 2014 to face sentencing for allegedly “assaulting a police officer.” While the only sign that the police officer was assaulted is a scratched finger, Maryam Al-Khawaja suffered a torn shoulder muscle as a result of rough treatment at the hands of police. She spent more than two weeks in prison in September following her return to Bahrain to visit her ailing father. More than 150 civil society organisations and individuals called for Maryam Al-Khawaja’s release in September, as did UN Special Rapporteurs and Denmark.

Other human rights defenders recently jailed include feminist activist and women’s rights defender Ghada Jamsheer, detained since 15 September 2014 for comments she allegedly made on Twitter regarding corruption at Hamad University Hospital. Jamsheer faced the Lower Criminal Court on 22 October 2014 on charges of “insult and defamation over social media” in three cases and a verdict is scheduled on 29 October 2014.

While the government of Bahrain continues to publicly tout efforts towards reform, the facts on the ground speak to the contrary. Human rights defenders remain targets of government oppression, while freedom of expression and assembly are increasingly under attack. Without the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners and human rights defenders, reform cannot become a reality in Bahrain.

We urge the international community, particularly Bahrain’s allies, to apply pressure on the government of Bahrain to end the judicial harassment of all human rights defenders. The government of Bahrain must immediately drop all charges against and ensure the release of human rights defenders and political prisoners, including Nabeel Rajab, Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Zainab Al-Khawaja, Ghada Jamsheer, Naji Fateel, Dr. Abduljalil Al-Singace, Nader Abdul Emam and all those detained for expressing their right to freedom of expression and assembly peacefully.

Signed,

Activist Organization for Development and Human Rights, Yemen

African Life Center

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Avocats Sans Frontières Network

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Human Rights Observatory (BHRO)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bahrain Salam for Human Rights

Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights (BYSHR)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

English PEN

European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Freedom House

Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Centre for Supporting Rights and Freedom, Egypt

International Independent Commission for Human Rights, Palestine

International Awareness Youth Club, Egypt

Kuwait Institute for Human Rights

Kuwait Human Rights Society

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LWRC)

Maharat Foundation

Nidal Altaghyeer, Yemen

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ – Italy)

Nonviolent Radical Party, Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT – Italy)

PEN International

Redress

Reporters Without Borders

Reprieve

Réseau des avocats algérien pour défendre les droits de l’homme, Algeria

Solidaritas Perempuan (SP-Women’s Solidarity for Human Rights), Indonesia

Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA)

Syrian Non-Violent Movement

The Voice of Women

Think Young Women

Women Living Under Muslim laws, UK

Youth for Humanity, Egypt

15 Oct 2014 | Press Releases, Uncategorized

- Awards honour journalists, campaigners and artists fighting censorship globally

- Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer

- Nominate at www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Beginning today, nominations for the annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2015 are open. Now in their 15th year, the awards have honoured some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes – from Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim to Syrian cartoonist Ali Farzat to education activist Malala Yousafzai.

The awards shine a spotlight on individuals fighting to speak out in the most dangerous and difficult of conditions. As Idrak Abbasov, 2012 award winner, said: “In Azerbaijan, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life… For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families. But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without truth.” Pakistani internet rights campaigner Shahzad Ahmad, a 2014 award winner, said the awards “illustrate to our government and our fellow citizens that the world is watching”.

Index invites the public, NGOs, and media organisations to nominate anyone they believe deserves to be part of this impressive peer group: a hall of fame of those who are at the forefront of tackling censorship. There are four categories of award: Campaigner (sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers); Digital Activism (sponsored by Google); Journalism (sponsored by The Guardian), and the Arts. Nominations can be made online via http://www.indexoncensorship.org/nominations

Winners will be flown to London for the ceremony, which takes place at The Barbican on March 18 2015. In addition, to mark the 15th anniversary of the Freedom of Expression awards, Index is inaugurating an Awards Fellowship to extend the benefits of the award. The fellowship will be open to all winners and will offer training and support to amplify their work for free expression. Fellows will become part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practice on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index, said: “The Index Freedom of Expression Awards is a chance for those whom others try to silence to have their voices heard. I encourage everyone, no matter where they are in the world, to nominate a free expression hero.”

The 2015 awards shortlist will be announced on January 27th 2015. Judges include journalist Mariane Pearl and human rights lawyer Sir Keir Starmer. The public will be asked to participate in selecting the winner of the Google Digital Activism award through a public vote beginning January 27th 2015. Sir Keir said: “Freedom of expression is part of the bedrock of civilised, democratic society. The Index on Censorship Awards have a material influence on promoting such freedom and both celebrating and protecting those who fight against censorship worldwide. That’s why Doughty Street Chambers chooses Index as its principal charity.”

For more information please contact David Heinemann: [email protected]

_______________________________________________________________________

NOTES FOR EDITORS

About Index on Censorship:

Index on Censorship is an international organisation that promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression. The inspiration of poet Stephen Spender, Index was founded in 1972 to publish the untold stories of dissidents behind the Iron Curtain and beyond. Today, we fight for free speech around the world, challenging censorship whenever and wherever it occurs. Index believes that free expression is the foundation of a free society and endorses Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.”

About The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards:

The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those deemed to be making the greatest impact in tackling censorship in their chosen area.

Awards categories:

Journalism – for impactful, original, unwavering journalism across all media (sponsored by The Guardian).

Campaigner – for campaigners and activists who have fought censorship and who challenge political repression (sponsored by Doughty St Chambers).

Digital Activism – for innovative uses of new technology to circumvent censorship and foster debate (sponsored by Google).

Arts – for artists and producers whose work asserts artistic freedom and battles repression and injustice.

Previous award winners include:

Journalism: Azadliq (Azerbaijan), Kostas Vaxevanis (Greece), Idrak Abbasov (Azerbaijan), Ibrahim Eissa (Egypt), Radio La Voz (Peru), Sunday Leader (Sri Lanka), Arat Dink (Turkey), Kareen Amer (Egypt), Sihem Bensedrine (Tunisia), Sumi Khan (Bangladesh), Fergal Keane (Ireland), Anna Politkovskaya (Russia), Mashallah Shamsolvaezin (Iran)

Digital/New Media: Bassel Khartabil (Palestine/Syria), Freedom Fone (Zimbabwe), Nawaat (Tunisia), Twitter (USA), Psiphon (Canada), Centre4ConstitutionalRights (US), Wikileaks

Advocacy: Malala Yousafzai (Pakistan), Nabeel Rajab (Bahrain), Gao Zhisheng (China), Heather Brooke (UK), Malik Imtiaz Sarwar (Malaysia), U.Gambira (Burma), Siphiwe Hlope (Swaziland), Beatrice Mtetwa (Zimbabwe), Hashem Aghajari (Iran)

Arts: Zanele Muholi (South Africa), Ali Farzat (Syria), MF Husain (India), Yael Lerer/Andalus Publishing House (Israel), Sanar Yurdatapan (Turkey)

You have received this email because email address ‘[email protected]’ is subscribed to ‘AWARDS 2015 Call For Nominations’.