16 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Guest Post, News

World leaders march in Paris following the recent attacks in France (Photo: European Council)

Jacob Mchangama is the founder and executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law. He has written and commented on human rights in international media including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The Economist, BBC World, Wall Street Journal Europe, MSNBC, and The Times. He has written and narrated the short documentary film “Collision! Free Speech and Religion”. He tweets @jmchangama

The brutal attack against Charlie Hebdo has seen European leaders rally round the fundamental value of freedom of expression.

French President Francois Hollande led the way by stating: “Today it is the Republic as a whole that has been attacked. The Republic equals freedom of expression.” Prime Minister David Cameron vowed that Britain will “never give up” the values of freedom of speech, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel called the events in Paris “an attack on freedom of expression and the press — a key component of our free democratic culture.” European Union President Donald Tusk stressed that “the European Union stands side by side with France after this terrible act. It is a brutal attack against our fundamental values, against freedom of expression which is a pillar of our democracy.”

This unified commitment to freedom of expression is both admirable and crucial in the aftermath of the killing of cartoonists armed with nothing more than ink, humour and courage. It is also true that freedom of expression is a fundamental European value and that (Western) Europe allows for a much freer debate than most other places in the world. However, European governments and institutions have long compromised this freedom through statements and laws that narrow the limits on permissible speech. Ironically some of these statements and laws target the very kind of offence that Charlie Hebdo excelled in.

Donald Tusk’s principled defence of freedom of expression stands in stark contrast to a 2012 joint statement issued by then EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton, as well as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League that “condemn[ed] any advocacy of religious hatred … While fully recognising freedom of expression, we believe in the importance of respecting all prophets”. The statement followed the furore over the crude anti-Islamic film “The Innocence of Muslims”, and suggests that mocking prophets is tantamount to religious hatred prohibited under international human rights law and thus exempted from the protection of freedom of expression.

The controversy over The Innocence of Muslims prompted none other than Charlie Hebdo to print its own depictions of Mohammed, including one showing Islam’s prophet naked. That decision drew stern condemnations from the French government. Then Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius remarked that “in the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?”

While Charlie Hebdo has won a number of lawsuits other French figures have been convicted or censored under French law. Last year comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala was banned from performing his comedy shows publicly, due to their anti-semitic content. And France is not alone. Swedish shock artist Dan Park was sentenced to six months imprisonment in 2014, over a number of purportedly racist posters deemed “gratuitously offensive” to minority groups by a Swedish court. The owner of the gallery that had displayed the cartoons was also convicted and the posters ordered destroyed.

In 2011, a prominent Austrian Islam-critic was convicted of “denigration of religious beliefs” for stating that the prophet Mohammed “had a thing for little girls”. An elderly Austrian man was found guilty of the same offence for yodelling while his Muslim neighbour was praying. In the United Kingdom, an atheist who left caricatures of the Pope, Mohammed and Jesus in a prayer room in John Lennon Airport was similarly convicted and sentenced to six months imprisonment, though the sentence was suspended. A TV personality’s disparaging social media comments about Scotland and Scots recently prompted Scottish police to tweet that it would “thoroughly investigate any reports of offensive or criminal behaviour online and anyone found to be responsible will be robustly dealt with”.

France and numerous other European countries also have bans against Holocaust denial. In 2010, a Muslim group claiming to expose free speech double standards in the aftermath of the Danish cartoon controversy was convicted after publishing a cartoon suggesting that Jews have made up the Holocaust.

When it comes to countering terrorism, European states increasingly target not only expression that incites terrorism but also expression that may constitute “glorification”. Exactly a week after the attack against Charlie Hebdo, Dieudonné once again ran afoul of the law and was detained over a Facebook post. According to Le Monde at least 50 other cases of terror apology have been opened against people in France since the attack. In Denmark, a number of Islamists have been prosecuted for glorifying terrorism following Facebook postings that seemingly approved of terrorism, including the assault on Charlie Hebdo. Recently British Home Secretary Theresa May unveiled plans that would ban “non-violent extremists” from using television and social media to spread their ideology.

While Europe has a sophisticated and elaborate regional system for the protection of human rights, these institutions have frequently sided with the censors over citizens. In 2008 the EU adopted a framework decision obliging all member states to criminalise certain forms of hate speech. The European Court of Human Rights has found the confiscation of a “blasphemous” film, the conviction of a French cartoonist mocking the victims of 9/11, and the banning of religious fundamentalist group Hizb-ut-Tahrir compatible with freedom of expression. The Council of Europe’s current High Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks, has called for all 47 member states to enact bans against Holocaust denial and gender based hate speech.

These non-exhaustive examples demonstrate that contemporary Europe’s approach to freedom of expression is far more complicated and far less principled than the statements made by its leading politicians in recent days suggest. It is an approach to freedom of expression based on the premise that social peace in increasingly multicultural societies requires restrictions on freedom of expression in order to avoid offending ethnic and religious groups. Thus in 2004, when Dutch film maker Theo Van Gogh was murdered by an Islamist offended by Van Gogh’s controversial and anti-Islamic film “Submission”, the Dutch minister of justice proposed to revive the country’s blasphemy law which had been disused since 1968. He argued that “if opinions have a potentially damaging effect on society, the government must act … It is not about religion specifically, but any harmful comments in general.”

Such sentiments might appeal to pragmatists in the wake of the tragedy in France. But there is little reason to think that restricting freedom of expression fosters tolerance and social cohesion across a Europe increasingly divided along ethnic and religious lines, and where anti-semitism and other forms of intolerance is on the rise. In fact such laws seem to fuel the feeling of separateness of modern Europe by legally protecting group identities against offence rather than fostering an identity rooted in common citizenship. While minorities may be offended by disparaging comments, insisting that freedom of expression be limited to protect them from racism and offence, is a very dangerous game at a time where far-right movements with questionable commitment to liberal democracy are on the rise. In this context it should not be forgotten that Dutch politician Geert Wilders once proposed banning the Quran and that the leader of Front National Marine Le Pen wants to ban religious head wear, including the Jewish kippah. The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence. Only by reaffirming a genuine and principled defence of freedom of thought, expression and religion can Europe hope to create a society built on real tolerance and respect for diversity, and where cartoonists neither have to fear gunmen nor jail, but only the moral judgment of their fellow citizens.

This guest post was published on 16 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Oct 2014 | About Index, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Statements

The undersigned 40 organisations call on the international community to publicly condemn the ongoing crackdown on human rights defenders, who face harassment, imprisonment, and forced exile for peacefully exercising their internationally recognised rights to freedom of expression and assembly. With parliamentary elections in Bahrain scheduled for 22 November, the international community must impress upon the government of Bahrain the importance of releasing peaceful human rights defenders as a precursor for free and fair elections.

Attacks against human rights defenders and free expression by the Bahraini government have not only increased in frequency and severity, but have enjoyed public support from the ruling elite. On 3 September 2014, King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa said he will fight “wrongful use” of social media by legal means. He indicated that “there are those who attempt to exploit social media networks to publish negative thoughts, and to cause breakdown in society, under the pretext of freedom of expression or human rights.” Prior to that, the Prime Minister warned that social media users would be targeted.

The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR) documented 16 cases where individuals were imprisoned in 2014 for statements posted on social media platforms, particularly on Twitter and Instagram. In October alone, some of Bahrain’s most prominent human rights defenders, including Nabeel Rajab, Zainab Al-Khawaja and Ghada Jamsheer, face sentencing on criminal charges related to free expression that carry years-long imprisonment.

Nabeel Rajab, President of the BCHR, Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), and Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), was arrested on 1 October 2014 and charged with insulting the Ministry of Interior and the Bahrain Defence Forces on Twitter. Rajab was arrested the day after he returned from an advocacy tour in Europe, where he spoke about human rights abuses in Bahrain at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, and visited foreign ministries throughout Europe.

On 19 October, the Lower Criminal Court postponed ruling on Rajab’s case until 29 October and denied bail. Rajab’s family was banned from attending the proceedings. Under Article 216 of the Bahraini Penal Code, Rajab could face up to three years in prison. We believe that Rajab’s detention and criminal case are in reprisal for his international advocacy and that the Bahraini authorities are abusing the judicial system to silence Rajab. More than 100 civil society organisations have called for Rajab’s immediate and unconditional release, while the United Nations called his detention “chilling” and argued that it sends a “disturbing message.” The United States and Norway called for the government to drop the charges against Rajab, and France called on Bahrain to respect freedom of expression and facilitate free public debate.

Zainab Al-Khawaja, who is over eight months pregnant, remains in detention since 14 October on charges of insulting the King. These charges relate to two incidents, one in 2012 and another during a court appearance earlier this month, where she tore a photo of the King. On 21 October, the Court adjourned her case until 30 October and continued her detention.

Zainab Al-Khawaja is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence in prison, following a grossly unfair trial, for calling for political reforms in Bahrain. Zainab Al-Khawaja has been subjected to continuous judicial harassment, imprisoned for most of last year and prosecuted on many occasions. Three additional trumped up charges were brought against her when she attempted to visit her father at Jaw Prison in August 2014 when he was on hunger strike. The charges are related to “entering a restricted area”, “not cooperating with police orders” and “verbal assault”.

Zainab’s sister, Maryam Al-Khawaja, was also targeted by the Bahraini government recently. The Co-Director of the GCHR is due in court on 5 November 2014 to face sentencing for allegedly “assaulting a police officer.” While the only sign that the police officer was assaulted is a scratched finger, Maryam Al-Khawaja suffered a torn shoulder muscle as a result of rough treatment at the hands of police. She spent more than two weeks in prison in September following her return to Bahrain to visit her ailing father. More than 150 civil society organisations and individuals called for Maryam Al-Khawaja’s release in September, as did UN Special Rapporteurs and Denmark.

Other human rights defenders recently jailed include feminist activist and women’s rights defender Ghada Jamsheer, detained since 15 September 2014 for comments she allegedly made on Twitter regarding corruption at Hamad University Hospital. Jamsheer faced the Lower Criminal Court on 22 October 2014 on charges of “insult and defamation over social media” in three cases and a verdict is scheduled on 29 October 2014.

While the government of Bahrain continues to publicly tout efforts towards reform, the facts on the ground speak to the contrary. Human rights defenders remain targets of government oppression, while freedom of expression and assembly are increasingly under attack. Without the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners and human rights defenders, reform cannot become a reality in Bahrain.

We urge the international community, particularly Bahrain’s allies, to apply pressure on the government of Bahrain to end the judicial harassment of all human rights defenders. The government of Bahrain must immediately drop all charges against and ensure the release of human rights defenders and political prisoners, including Nabeel Rajab, Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Zainab Al-Khawaja, Ghada Jamsheer, Naji Fateel, Dr. Abduljalil Al-Singace, Nader Abdul Emam and all those detained for expressing their right to freedom of expression and assembly peacefully.

Signed,

Activist Organization for Development and Human Rights, Yemen

African Life Center

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Avocats Sans Frontières Network

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Human Rights Observatory (BHRO)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bahrain Salam for Human Rights

Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights (BYSHR)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

English PEN

European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Freedom House

Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Centre for Supporting Rights and Freedom, Egypt

International Independent Commission for Human Rights, Palestine

International Awareness Youth Club, Egypt

Kuwait Institute for Human Rights

Kuwait Human Rights Society

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LWRC)

Maharat Foundation

Nidal Altaghyeer, Yemen

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ – Italy)

Nonviolent Radical Party, Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT – Italy)

PEN International

Redress

Reporters Without Borders

Reprieve

Réseau des avocats algérien pour défendre les droits de l’homme, Algeria

Solidaritas Perempuan (SP-Women’s Solidarity for Human Rights), Indonesia

Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA)

Syrian Non-Violent Movement

The Voice of Women

Think Young Women

Women Living Under Muslim laws, UK

Youth for Humanity, Egypt

3 Jun 2014 | Campaigns, Politics and Society

As part of its effort to map media freedom in Europe, Index on Censorship’s regional correspondents are monitoring media across the continent. Here are incidents that they have been following.

AUSTRIA

Police block journalists’ access to protest

Police denied journalists access to the site where members of the right-wing group “Die Identitären” were demonstrating on May 17. News website reports and a video from Vice News show police using excessive force against demonstrators. The Austrian Journalists’ Club described the police’s treatment of journalists as one of the recent “massive assaults of the Austrian security forces on journalists” and called for journalists to report breeches in press freedom to the club. (Austrian Journalists’ Club) (Twitter)

CROATIA

Croatian law threatens journalists

Croatia’s new Criminal Code establishes the offence of “humiliation”, a barrier to freedom of expression that has already claimed its first victim among journalists – Slavica Lukić, of newspaper Jutarnji list. A Croatian journalist is likely to end up in court and be sentenced for “humiliation” for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek, Croatia’s fourth largest city, is accused by the judiciary of having received a bribe of 2,000 Euros to pass some students during an examination. For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news. According to Article 148 of the Criminal Code, introduced early last year, the court may sentence a journalist (or any other person that causes humiliation to others) if the information published is not considered as of public interest.

CYPRUS

Cyprus’ Health ministry Director General accused of 30million scandal whitewash

9.5.2014: The former Director General of the Ministry of Health, Christodoulos Kaisis, is alleged to have censored the responses of two ministerial departments during an audit regarding a 30 million scandal of mispricing of drugs. He did not send the requested information to the Audit Committee of the Parliament. (Politis)

DENMARK

Journalists convicted for violating law protecting personal information

On May 22 2014 two Danish journalists got convicted for violated Danish law protecting personal information because they named twelve pig farms in Denmark as sources of the spread of MRSA, a strain of drug-resistant bacteria. They argue they had been trying to investigate the spread of MRSA, but the government had wanted to keep that information secret. Their defense attorney claims revealing the names was appropriate because ‘there is public interest in openness about a growing health hazard’. The penalty was up to six months imprisonment, but the judge ruled they have to pay 5 day-fines of 500 krone (68 euro). The verdict is a ‘big step back for the freedom of press’ in Denmark, one of the journalists, Nils Mulvad said after the trial.

FINLAND

ECHR rejects journalist’s free speech claim

On April 29 2014, the European Court of Human Rights rejected a free speech claim over a defamation conviction by a Finnish journalist. In August 2006 journalist Tiina Johanna Salumaki and her editor in chief were convicted of defaming a businessman. The newspaper published a front page story, asking whether the victim of a homicide had connections with this businessman, K. U. The court ruled that Salumaki and the newspaper had to pay damages and costs to K. U. According to Salumaki her right to free expression was breached.

GERMANY

Journalist’s phone tapped by state police

A journalist’s telephone conversation with a source was tapped by state criminal police. The journalist, Marie Delhaes, spoke about the police’s subsequent contact with her on the media show ZAPP on German public television. Police asked her to testify as a witness in a criminal case against the source she communicated with, an Islamist accused of inciting others to fight with rebels in Syria. Delhaes was threatened with a fine of 1000 Euros if she were to refuse to testify. She has since claimed reporter’s privilege, protecting her from being forced to testify in a case she worked on as a journalist. (NDR: ZAPP)

Local court rules police confiscation of podcasters’ recording equipment and laptops was illegal

A court ruled on May 22 that police officers’ 2011 confiscation of recording equipment and laptops in a van used by the podcasters Metronaut and Radio Freies Wendland was illegal. The podcasters were covering the transport of atomic waste through Germany and were interviewing anti-atomic energy activists. When the equipment was confiscated, police officers also asked the podcasters to show official press passes, which they did not have. The court ruled that police failed to determine the present danger of the equipment in the van before confiscating it for three days. Metronaut later sued the police. (Metronaut) (Netzpolitik.org)

GREECE

Lost in translation

The Greek newswire service ANA-MPA is accused by its own Berlin correspondent of engaging in pro government propaganda after a translation of the official announcement by the German Chancellor regarding Angela Merkel’s Athens visit is ‘revised’, eliminating all mentions of ‘austerity,’ replacing the word with ‘consolidation’. (The Press Project)

Radio advert from pharmacists banned

A union representing pharmacists in Attica has accused the government of censorship, after it was told it may not broadcast adverts deemed by the authorities to be a political nature in the run up to elections later this month. (Eleftherotypia, English Edition)

ITALY

The regional Italian newspaper “L’ora della Calabria” is shut down due to political pressure

After the complaint, in February, against the pressures to not refer in an article to the son of senator Antonio Gentile, and to the block of the printing presses on the same day (an episode that is under investigation by the judiciary), now the newspaper L’Ora della Calabria is closing. The publications have been halted, even that of the website. This was decided by the liquidator of the news outlet, who had for a long time been in financial difficulties.

Reporter sued for criticizing the commissioner

Marilena Natale criticized a legal consultancy that cost €60’000 in the town whose City Council has dissolved for mafia, and which suffers from thirst due to the closure of the artesian wells. Ms Marilena Natale, reporter for the Gazzetta di Caserta and +N, a local all-news television channel, was sued. She had in the past already been the victim of other complaints and assaults. To denounce the journalist was Ms Silvana Riccio, the Prefectural Commissioner who administers the City of Casal di Principe, fired due to Camorra infiltrations. The Commissioner Riccio feels defamed by a series of articles written by the reporter in which the decision to spend €60’000 for legal advice is criticized, while the citizens suffer thirst due to the closure of numerous wells due to groundwater pollution.

MACEDONIA

A band to defend press freedom

24.4.2014: A music band called “The Reporters” was created recently by famous Macedonian journalists. The project aims to defend press freedom in Macedonia and support their colleagues who are facing censorship and other limitations. (Focus)

Macedonian government member encourages censorship in the press

14.5.2014: The Macedonian government quietly encourages censorship in the press, buys the silence of the media through government advertising and at the same time gives carte blanche to use hate speech, said Ricardo Gutierrez, Secretary General of the European Federation of Journalists during a conference of the Council of Europe in Istanbul on the 14th of May. (Focus)

Macedonian Journalists ‘Working Under Heavy Pressure’

24.3.2014: Sixty-five per cent of Macedonian journalists who responded to a survey publish last March, have experienced censorship and 53 per cent are practicing self-censorship, says the report, entitled the ‘White Book of Professional and Labour Rights of Journalists’. (Balkan Insight)

MALTA

The Nationalist Party complains of censorship by the public broadcaster PBS

The Nationalist Party (PN) has accused PBS of censoring it in its coverage of the European parlament elections campaign. The party noted that PBS did not send a journalist to report on Simon Busuttil’s visit to Attard and Co on Tuesday and it had also failed to sent a reporter to cover a press conference addressed by PN Secretary General Chris Said in Gozo this morning. “This is nothing but censorship during an electoral campaign,” the PN said. The PN has also complained with the national TV station on its choice of captions for news items carried in the bulletin.

NETHERLANDS

Press photographers’ equipment seized

During a raid on a trailer park in Zaltbommel on may 27 2014, the cameras of two press photographers were seized by the police. According to the spokesman of the court of Den Bosch the police took the cameras after several warnings. The photographers were on the public road. After a few days the two photographers got their cameras back, but their memory cards with the photo’s are still not returned. The NVJ, de Dutch journalist Union, has pledged to stand with one of the journalists in his claim to get his photo’s back.

SERBIA

Serbia Floods Interrupt Free Flow of News

Websites criticising the government’s handling of the flood disaster in Serbia have come under attack from hackers in what some call a covert act of censorship. Creators of the Serbian blog Druga Strana, which published critical posts on the Serbian state’s handling of the flooding, were forced to shut it down on Tuesday after repeat attacks on the site. “The site has been under heavy attack so we decided to shut it down in order not to compromise other sites on the server,” Nenad Milosavljevic said.

Serbian Newspaper Editor Fired After Criticising Govt

The sacking of Srdjan Skoro, editor of state-owned newspaper Vecernje Novosti, who publicly criticized Serbia’s new ministers, has been described as an attack on independent media. Skoro said that he was told that he was no longer the editor of the Serbian tabloid Vecernje Novosti on Friday morning, but was given no explanation for his sacking. “I have been told to find another job and that I would perhaps do better there,” Skoro said. He said that although no one has said it directly, the reason for his dismissal was his recent appearance on public service broadcaster RTS’s morning TV show, in which he openly criticised some candidates for posts in the new Serbian cabinet.

SERBIA

Media in Serbia: the government’s double standard

Aleksandar Vučić’s government seems to be adopting a double standard when it comes to media: one for the EU, one for Serbia, with tight control over newspapers and television stations. I do not believe in chance, and I know “where all this is coming from and who is behind it”. Thus Aleksandar Vučić, Prime Minister of Serbia, commented the statement by Michael Davenport, head of the EU Delegation, about “unpleasant and unacceptable” issues in Serbian media. Davenport said that elements of investigations conducted by the judiciary are leaked to the public through some media, and that the “cases” of parallels being made between representatives of civil society and crime are “a clear violation of the ethical standards of the media”.

SLOVENIA

If you can’t stand the heat, don’t turn up the oven: Strasbourg Court expands tolerance for criticism of xenophobia to criticism of homophobia

On the 17th of April 2014, the European Court of Human Rights issued a judgement in the case of Mladina v. Slovenia. In this case, the Court further develops its standing case law on “public statements susceptible to criticism”. When assessing defamation cases, the Court has in the past found that authors of such statements should show greater resilience when offensive statements are in turn addressed to them.

SPAIN

The government threats to censor social media

“We have to combat cybercrime and promote cybersecurity, and to clean up undesirable social media.” These were the words of the Spanish Minister of Interior, Jorge Fenández Díaz, after the wave of comments published on social media about the assassination of Isabel Carrasco, president of the Province of León and member of the government party (Pp). Although the majority expressed their condolences to the family of the victim, there were some that took advantage of the moment to openly criticize the politician, including mocking her assassination. These tweets generated a strong reaction of rejection in certain circles. For their part, Tweeters have reacted by creating two hashtags, #TuiteaParaEvitarElTalego (Tweet to stay out of Jail) y #LaCárcelDeTwitter [Twitter Prison], through which many Internet-users vent their frustration against politicians who want to silence them. On the other hand the Federal Union of Police has published a note that proposes a change in legislation with the alleged intent of protecting minors, relatives of victims, and users in general.

Extremadura public television don’t broadcast the motion of censure on the regional president Monago

Extremadura public television did not broadcast the debate and subsequent vote of no confidence on the regional president and member of the government party Antonio Monago on May 14th, despite the political relevance of the issue (the debate was broadcasted only trough the TV’s website). The workers called a protest to consider a motion of censure “is a matter of highest public interest and should be covered by public broadcast media in all its channels”, as expressed by the council in a statement.

TURKEY

Founder of satirical website sentenced for discussion thread considered insulting to Islam

The founder of the satirical online forum Ekşi Sözlük was given a suspended sentence of ten months in prison. Forty authors for the user-generated website were detained in connection to a complaint that a thread in an Ekşi Sözlük forum was insulting to Islam. Founder Sedat Kapanoğlu and another defendant received suspended prison sentences for insulting religious values. (Hürriyet Daily News)

Journalists recently released from prison speak out against government using release for political capital

Journalists who had been imprisoned for two years in connection to the KCK case were released this month. Several of the released journalists gave a press conference on May 13 condemning the government’s manipulation of the case to improve its own human rights and press freedom standing internationally. Yüksek Genç, a journalist who spoke at the press conference, said that the amount of journalists in prison can not be the only measure of Turkey’s press freedom, since the government has other ways of meddling in media and putting economic pressure on news organisations. A number of journalists have been released from prison this year after a court regulation was changed, enforcing a shorter maximum detention time for prisoners awaiting trial on terrorism charges. (Bianet)

Police detain and injure journalists at May 1 protests

During May Day protests in Istanbul, police blocked journalists’ access to demonstrating crowds and demanded they show official press passes to enter the area around Taksim Square. At least 12 journalists were injured by police officers using rubber bullets, teargas and bodily force. Deniz Zerin, an editor of the news website t24, was detained trying to enter his office and held for three days. (Bianet)

Prominent journalist sentenced to ten months in prison for tweet insulting Prime Minister Erdoğan

On April 28, the journalist Önder Aytaç was sentenced to ten months in prison for a 2012 tweet that the court ruled to be insulting to Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan under blasphemy laws. The tweet included a word that translates to “my chief” or “my master” (relating to Erdoğan), but included an additional letter at the end that made the word vulgar. Erdoğan sued Aytaç, who maintained that the extra letter in his tweet was a typo. (Medium)

For more reports or to make your own, please visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

With contributions from Index on Censorship regional correspondents Giuseppe Grosso, Catherine Stupp, Ilcho Cvetanoski, Christina Vasilaki, Mitra Nazar

This article was posted on June 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News

In France, Bob Dylan is being officially investigated for “incitement to hatred” against Croats for comparing their relationship to Serbs with that between Nazis and Jews in an interview.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Freedom of information

Freedom of information is an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression. Without the ability to access information held by states, individuals cannot make informed democratic choices. Many EU member states have failed to adequately protect freedom of information and the Commission has been criticised for its failure to adequately promote transparency and uphold its commitment to freedom of information.

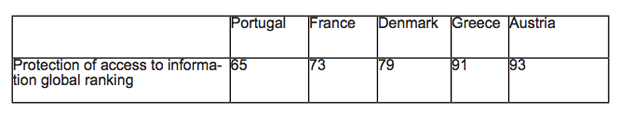

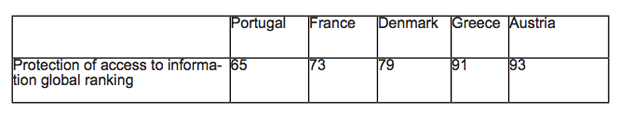

When it comes to assessing global protection for access to information, not one European Union member state ranks in the list of the top 10 countries, while increasingly influential democracies such as India do. Two member states, Cyprus and Spain, are still without any freedom of information laws. Of those that do, many are weak by international standards (see table below).

In many states, the law is not enforced properly. In Italy, public bodies fail to respond to 73% of requests.

The Council of Europe has also developed a Convention on Access to Official Documents, the first internationally binding legal instrument to recognise the right to access the official documents of public authorities. Only seven EU member states have signed up the convention.

Since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, both member states and EU institutions are both bound by freedom of information commitments. Article 42 (the right of access to documents) of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights now recognises the right to freedom of information for EU documents as a fundamental human right Further, specific rights falling within the scope of freedom of information are also enshrined in Article 41 of the Charter (the right to good administration).

As a result, the European Commission has embedded limited access to information in its internal protocols. Yet, while the European Parliament has reaffirmed its commitment to give EU citizens more access to official EU documents, it is still the case that not all EU institutions, offices, bodies and agencies are acting on their freedom of information commitments. The Danish government used their EU presidency in the first half of 2012 to attempt to forge an agreement between the European Commission, the Parliament and member states to open up public access to EU documents. This attempt failed after a hostile response from the Commission. Attempts by the Cypriot and Irish presidencies to unblock the matter in the Council also failed.

This lack of transparency can and has impacted on public’s knowledge of how decisions that affect human rights have been made. The European Ombudsman, P. Nikiforos Diamandouros, has criticised the European Commission for denying access to documents concerning its view of the United Kingdom’s decision to opt out from the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. In 2013, Sophie in’t Veld MEP was barred from obtaining diplomatic documents relating to the Commission’s position on the proposed Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA).

Hate speech

Across the European Union, hate speech laws, and in particular their interpretation, vary with regard to how they impact on the protection for freedom of expression. In some countries, notably Poland and France, hate speech laws do not allow enough protection for free expression. The Council of the European Union has taken action on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by promoting use of the criminal law within nation states in its 2008 Framework Decision. Yet, the Framework Decision failed to adequately protect freedom of expression in particular on controversial historical debate.

Throughout European history, hate speech has been highly problematic, from the experience and ramifications of the Holocaust through to the direct incitement of ethnic violence via the state run media during wars in the former Yugoslavia. However, it is vital that hate speech laws are proportionate in order to protect freedom of expression.

On the whole, the framework for the regulation of hate speech is left to the national laws of EU member states, although all member states must comply with Articles 14 and 17 of the ECHR.[1] A number of EU member states have hate speech laws that fail to protect freedom of expression –- in particular in Poland, Germany, France and Italy.

Article 256 and 257 of the Polish Criminal Code criminalise individuals who intentionally offend religious feelings. The law criminalises public expression that insults a person or a group on account of national, ethnic, racial, or religious affiliation or the lack of a religious affiliation. Article 54 of the Polish Constitution protects freedom of speech but Article 13 prohibits any programmes or activities that promote racial or national hatred. Television is restricted by the Broadcasting Act, which states that programmes or other broadcasts must “respect the religious beliefs of the public and respect especially the Christian system of values”. In 2010, two singers, Doda and Adam Darski, where charged with violating the criminal code for their public criticism of Christianity.[2] France prohibits hate speech and insult, which are deemed to be both “public and private”, through its penal code[3] and through its press laws[4]. This criminalises speech that may have caused no significant harm whatsoever to society, which is disproportionate. Singer Bob Dylan faces the possibility of prosecution for hate speech in France. The prosecutor’s office in Paris confirmed that Dylan has been placed under formal investigation by Paris’s Main Court for “public injury” and “incitement to hatred” after he compared the relationship between Croats and Serbs to that of Nazis and Jews.

The inclusion of incitement to hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation into hate speech laws is a fairly recent development. The United Kingdom’s hate speech laws contain specific provisions to protect freedom of expression[5] but these provisions are not absolute. In a landmark case in 2012, three men were convicted after distributing leaflets in Derby depicting a mannequin in a hangman’s noose and calling for the death sentence for homosexuality. The European Court of Human Rights ruled on this issue in its landmark judgment Vejdeland v. Sweden, which upheld the decision reached by the Swedish Supreme Court to convict four individuals for homophobic speech after they distributed homophobic leaflets in the lockers of pupils at a secondary school. The applicants claimed that the Swedish Supreme Court’s decision to convict them constituted an illegitimate interference with their freedom of expression. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 10, noting even if there was, the interference served a legitimate aim, namely “the protection of the reputation and rights of others”.

The widespread criminalisation of genocide denial is a particularly European legal provision. Ten EU member states criminalise either Holocaust denial, or the denial of crimes committed by the Nazi and/or Communist regimes. At EU level, Germany pushed for the criminalisation of Holocaust denial, culminating in its inclusion from the 2008 EU Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. Full implementation of the Framework Decision was blocked by Britain, Sweden and Denmark, who were rightly concerned that the criminalisation of Holocaust denial would impede historical inquiry, artistic expression and public debate.

Beyond the 2008 EU Framework Decision, the EU has taken specific action to deal with hate speech in the Audiovisual Media Service Directive. Article 6 of the Directive states the authorities in each member state “must ensure by appropriate means that audiovisual media services provided by media service providers under their jurisdiction do not contain any incitement to hatred based on race, sex, religion or nationality”.

Hate speech legislation, particularly at European Union level, and the way this legislation is interpreted, must take into account freedom of expression in order to avoid disproportionate criminalisation of unpopular or offensive viewpoints or impede the study and debate of matters of historical importance.

[1] ‘Article 14 – discrimination’ contains a prohibition of discrimination; ‘Article 17 – abuse of rights’ outlines that the rights guaranteed by the Convention cannot be used to abolish or limit rights guaranteed by the Convention.

[2] The police charged vocalist and guitarist Adam Darski of Polish death metal band Behemoth with violating the Criminal Code for a performance in 2007 in Gdynia during which Darski allegedly called the Catholic Church “the most murderous cult on the planet” and tore up a copy of the Bible; singer Doda, whose real name is Dorota Rabczewska, was charged with violating the Criminal Code for saying in 2009 that the Bible was “unbelievable” and written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some kind of herbs”.

[3] Article R625-7

[4] Article 24, Law on Press Freedom of 29 July 1881

[5] The Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A[12] to criminalising attempting to “stir up religious hatred.” A further provision to protect freedom of expression (Section 29J) was added: “Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system.”