1 Feb 2023 | Iran, News and features

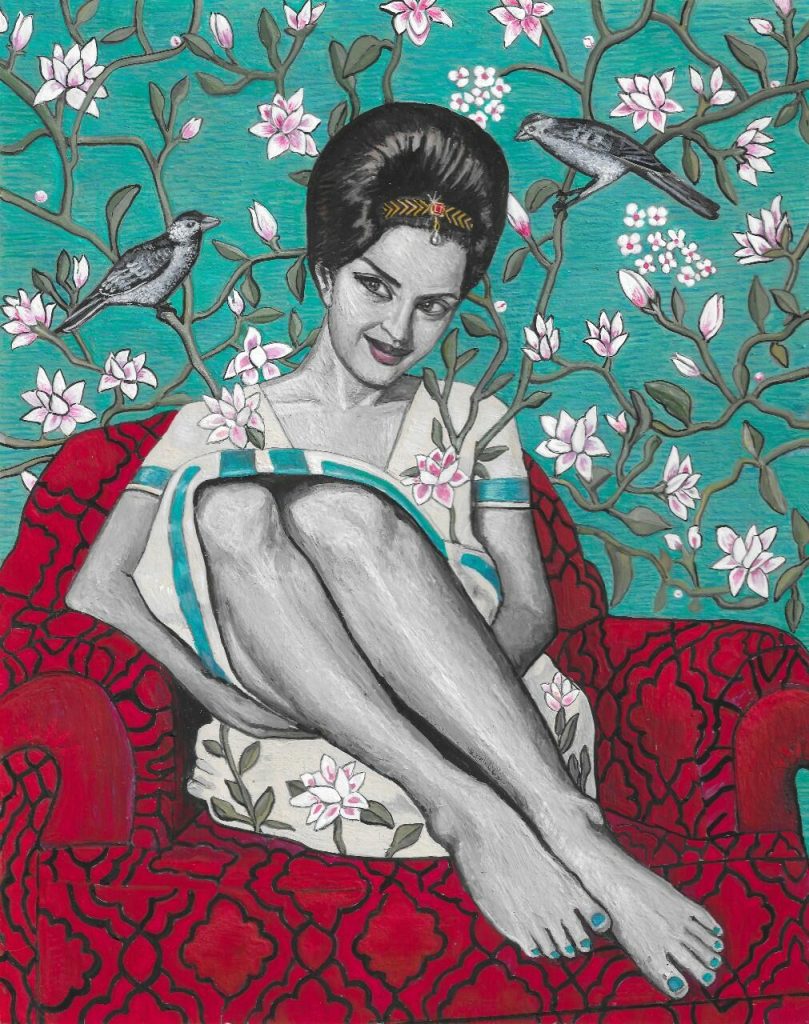

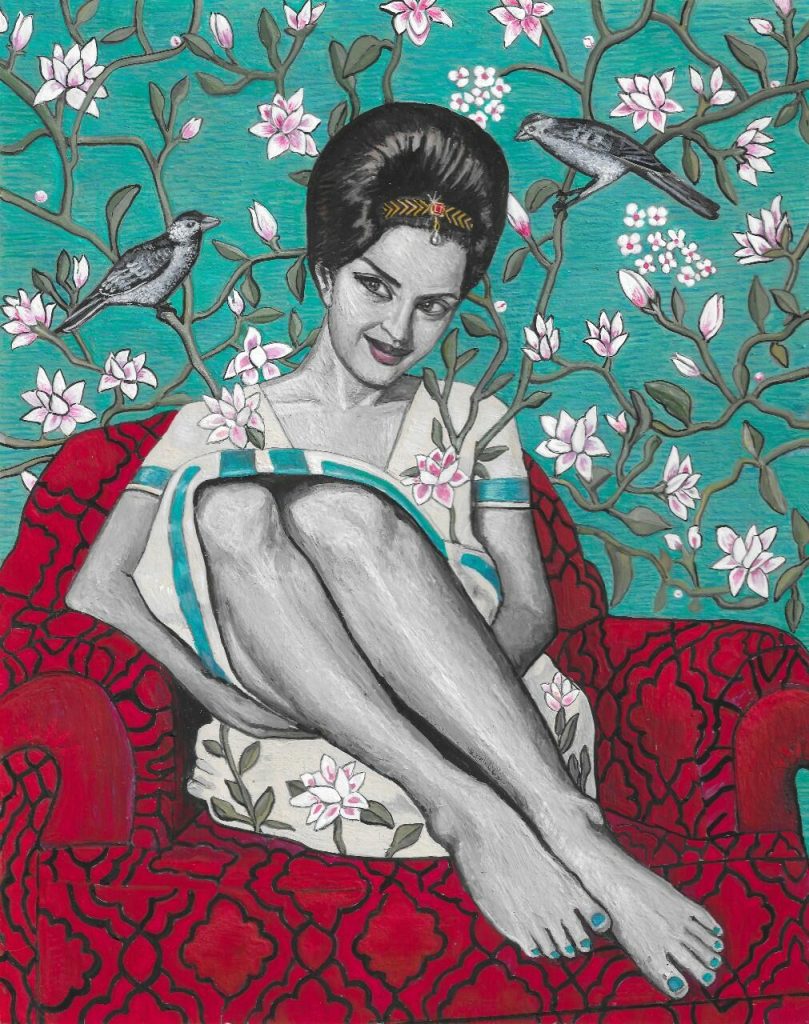

Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019 Credit: Soheila Sokhanvari, courtesy Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

The long, winding path of The Curve art gallery at London’s Barbican Centre has been transformed into a devotional space. The cavernous room is dimly lit and echoes with the calming voices of female Iranian singers. Sprawling, Islamic, geometric patterns roll down the tall walls which are splintered with the light projected onto them by dazzling mirrored sculptures. Apart from the female voices, it feels like a mosque.

Take a closer look, and the walls are scattered with traditional Persian miniatures, depicting women whose histories have been erased in Iran. In painstaking detail, Soheila Sokhanvari’s portraits provide a snapshot into women’s lives pre-revolution. Born in Shiraz in the Fars Province of Iran, she came to England in 1978, just a year before the Islamic Revolution. But Sokhanvari remains enchanted with the country she left behind. Her miniatures depict unveiled and glamorous women, creative dissidents who pursued careers in a country awash with Western style but not its freedoms.

“I can relate directly to the women in my paintings,” she told Index. “Like them I am an artist but, unlike them, I am able to pursue my career, wear what I want and act as I want, and the idea that one day someone could take my freedom away from me is unthinkable”.

The portraits are displayed without names or biographical info but, by scanning a QR code, we are guided through the exhibition by their stories. There are 28 in total: actors, singers, poets, writers, dancers and film directors, all of which were either forced into silence or exile in 1979, when the Islamic Revolution led to a rollback in women’s legal rights. Much of their work is censored in Iran today. “I knew of many of the women from my own experience and time in Iran as a young girl,” Sokhanvari explained. “They were my idols, but finding out more information about the lives of several of the women took lots of research – they were essentially erased from the record by the regime”. She said that a small number of the women – like singer and actress Googoosh – are very famous, but that several had tragically died too young and were hard to trace.

The exhibition draws the spotlight back onto these talented women for which, she says, she feels a deep loss. The portraits beautifully capture this feeling: a simultaneous celebration of their bravery and a mourning of their freedoms. Vivid patterns and clothing contrast monochromatic faces, which make the pictures feel both vibrant and ghostly. The use of new and old multimedia was significant in telling these stories too. “I painted my portraits in the ancient technique of egg tempera, onto calf vellum, and I included films in which the women starred, ” Sokhanvari said. Two holograms of dancing Iranian actors Kobra Saeedi and Jamileh are also hidden in boxes. “I wanted the viewers to see these women, to watch them dance and to hear them sing, since they have been banned from these platforms.” The broadcasting of women’s voices in public is illegal in Iran. “I wanted to show these women at the height of their creativity, to show them as the sensational artists that they are, and using multimedia helped to achieve this immersive experience.”

This contrast of old and new is fitting. While the exhibition was curated without sight of the current unrest in Iran, the portraits certainly gain a tragic poignancy because of it. The brave women of Sokhanvari’s portraits embody much of what people are fighting for today. “Young women are at the front of this revolution and that is what gives it its power,” she told Index. “I feel a new sense of positivity and hope that perhaps we will see the end of this regime, but simultaneously I feel pain and bitterness that it is at the cost of so many bright lives.”

Although she doesn’t describe her artwork as a protest, she says that the message is political.

“What is happening in Iran can no longer be seen as just another protest, it is a revolution and I stand in solidarity with my sisters.” I asked if her portraits reflect a lost past or a hopeful future. She says both.

‘Rebel Rebel’ at The Curve, Barbican is open until 26 February 2023

11 Jan 2023 | Iran, News and features

As of last week four young men have been executed at the hands of the Iranian regime. They were arrested while participating in the recent protests sparked by the death in custody of Jina (Mahsa) Amini. After being tortured and forced to make confessions, they faced grossly unfair show trials. Without strong condemnation, this death toll will grow – there are many more who have currently been sentenced to execution. Here we remember those four who died fighting for freedom.

Mohammad Mehdi Karami

Mohammad Mehdi Karami was a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian man From Karaj in the Alborz province of Iran. He was arrested on 5 November 2022 for allegedly killing a member of the security forces and was executed just two months later on 7 January. At the time of his death, he had been on hunger strike for four days, demanding access to his lawyer.

Mohammad was a national karate champion who had several national titles. In an interview with Etemad newspaper, his father describes Mohammad as “an athlete who constantly strived to achieve honours”. In the video, uploaded on 12 December, he pleads with authorities to release his son and recounts various attempts to contact the lawyer who was appointed to his son by the judiciary, all of which were ignored. He describes a phone conversation with Mohammad in which the young man sobbed and begged his father not to tell his mother about his sentence. “Mehdi’s mother is very attached to him,” he said. “If something happens to Mehdi, our lives will also end”.

Mohammad attempted to appeal his sentence but was denied. His father maintains that on their final phone call, his son swore to have not committed murder. The family was not allowed to see him to say goodbye before he was hanged. They camped outside the Rajai Shahr prison in Karaj. The prison guards reassured them that he was alive and well. They told the family that rumours of execution were false and to return home. Mohammad’s grave is in Eshtehard, Alborz. Mehdi Beyk, the journalist who interviewed Karami’s parents, was later arrested.

Seyed Mohammad Hosseini

Seyed Mohammad Hosseini, 39, was a worker remembered for volunteering with children by a German parliamentarian who advocated his case.

Hosseini was convicted for allegedly murdering a member of the security forces and was executed on 7 January. His lawyer, Ali Sharifzadeh Ardakani, described meeting him in prison: “He was in tears, talking about how he was tortured and beaten while blindfolded.” Ardakani previously revealed that the court had denied him access to case materials to defend his client during the entire interrogation and trial process.

Seyed Mohammad was an orphan with no immediate family to receive his body after his execution. His brother was also arrested but disappeared after release. Mohammad’s friends weren’t allowed to visit him in prison. He was buried near Mohammad Mehdi Karami’s grave in Eshtehard, Alborz. Mohammad Mehdi’s family attended Mohammad’s grave, lit candles and placed flowers there in his memory.

Majidreza Rahnavard

Majidreza Rahnavard was publicly executed on 12 December, just 23 days after his arrest.

Majidreza Rahnavard. Photo: 1500tasvir_en (CC BY-SA 4.0)

He was charged with allegedly fatally stabbing two Basij militia volunteers. The 23-year-old was denied a lawyer of his choice for his trial.

The lawyer he was given did not put up a defence. Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam, director of Norway-based Iran Human Rights, tweeted that Rahnavard was sentenced based on “coerced confessions, after a grossly unfair process and a show trial”.

Majidreza’s mother was not told about his execution until after his death. Activist collective 1500tasvir said on Twitter that the family received a telephone call from an official at 07:00 local time. They said: “We have killed your son and buried his body in Behesht-e Reza cemetery.”

In a video aired by authorities, Rahnavard appears blindfolded, surrounded by masked men. He is asked what he wrote in his will. He says: “I don’t want anyone to pray, or to cry. I want everyone to be happy and play happy music.”

Mohsen Shekari

Mohsen Shekari, 23, worked in a cafe. He was arrested on 25 September for trying to stop security forces from attacking protesters in Tehran. He was the first person to be executed by the state on 8 December after being convicted of injuring a member of Iran’s Basij militia or “waging war against God”. While authorities asserted that he wielded a machete, Shekari’s family disputed this version of events, claiming he used non-violent means to separate protesters and security forces.

Mohsen Shekari. Photo: Unknown (CC BY 4.0).

Shekari’s uncle told The Guardian that authorities did not release his body. Other families of dead protesters have made similar statements. He said that the family had been sent to two cemeteries, but that when they arrived at the locations, they were told the body was not there. Although Mohsen’s mother saw her son the night before his hanging, she was ordered to remain silent about his fate.

Shekari’s judge had the choice to impose a lighter sentence and chose not to do so. Shekari appealed the verdict but was denied by Iran’s Supreme Court, despite the fact that he was not represented by his lawyer at the time of the appeal.

6 Jan 2023 | FEATURED: Mark Frary, Iran, News and features

Ramita Navai in Iran in 2005, at a time when women journalists were temporarily allowed in to report on football matches

Up to 20,000 people have now been detained as a result of the protests that have wracked Iran in the past three months. Those who have been detained have been subject to physical and psychological torture, rape and been made to make forced confessions. Some, including 22-year-old Mahsa (Jina) Amini whose death sparked the current protests, have died in custody.

The British-Iranian investigative journalist and documentary maker Ramita Navai knows only too well what those who have been detained are facing. She has been detained by the Iranian authorities several times over the years.

Her first arrest came just after she had started working as Tehran correspondent for The Times and was covering the anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

“I was at a rally with a lot of other journalists and I was interviewing some Iranians. Before I knew it, two undercover intelligence agents had taken me away; none of my colleagues saw me being taken. It was a terrifying experience. They took me to an abandoned warehouse with broken windows and flexes hanging from the ceiling and there was an armed man standing outside the room. They took all my possessions and carried a table and chairs into the room before starting with a good cop/bad cop routine. It was very manipulative psychologically and was designed to break me. They started telling me that I had been asking anti-revolutionary questions and said I had been telling people how to answer. It was all lies but I was utterly unprepared for this.”

Her interrogators asked her whether she had heard of Zahra Kazemi, a Canadian-Iranian photojournalist who had been killed in police custody shortly before Navai had arrived in Iran.

“Every journalist knew what had happened to her and they were hinting that I would suffer the same fate. I was so petrified I started sobbing.”

Navai was one of the lucky ones. A few hours after being taken, one of her journalist colleagues, Jim Muir of the BBC, noticed she was missing and started talking to the Iraniansat the rally. One whispered to him that they had seen her being taken away.

“He phoned up the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance and said we know you have got her, you had better release her otherwise I am going to cause a fuss about this.”

Navai was released shortly afterwards.

Since then Navai has won numerous awards for her documentary work, including an Emmy for her PBS Frontline documentary Syria Undercover in 2012 and a Royal Television Society Journalism Award for her documentary on tracking down refugee kidnap gangs for Channel 4.

But it is Iran, the country of her birth, where her heart lies.

Her 2014 book City of Lies, which won her the Royal Society of Literature’s Jerwood Award for non-fiction, tells the stories of ordinary Iranians forced to live extraordinary lives: the porn star, the ageing socialite, the assassin and enemy of the state who ends up working for the Republic, the dutiful housewife who files for divorce, and the old-time thug running a gambling den.

Tehran, the City of Lies of the title, is described with romantic nostalgia but rails against the hypocrisy of the regime.

Navai feels there is “no turning back” from the current protests.

“This time feels very different. I think the protests are unlike anything we have ever seen. Significantly, they span all social classes, ethnicities and the protests have happened in every one of Iran’s provinces. The protests have been a unifying force, uniting Iranians of all colours against the regime. I don’t think the regime will fall imminently although I do think something has shifted and there is no going back from that. I think a very different future for Iran has now become a reality in a way that it wasn’t a year ago.”

She adds, “The most organised groups seem to be the Iranian feminist and women’s rights networks because they have been used to mobilising for such a long time. They are used to being arrested and imprisoned. They issue secret missives and are coordinating with some of the activists in prison.”

Navai and her mother Laya at a demonstration in London in support of the Iranian protests

Navai believes it is the moment for Iranian women and those of Generation Z in particular.

“The women’s groups were crushed in 2009 – they were a thorn in the side of the regime. What we are seeing now is a strengthening and a rising up,” she says. “In 2009, it was people my age who were and are very fearful of the regime. The younger generation – Generation Z – are absolutely fearless. My generation always felt like they had something to lose. The regime is brilliant at playing this game of giving people just enough freedom to shut them up. This younger generation have grown up in a very different world, a completely connected Iran in which they have been influenced by global popular culture. They know what is out there in the world. They know all the opportunities that should be open and available to them and they are angry and they are fearless.”

She believes a sexual awakening is also happening in Iran.

“We are talking about this being a women-led uprising, partly this is because this sexual awakening has changed the socio-cultural dynamics for Generation Z. In real terms, virginity is not the thing it used to be. So many couples are living together outside marriage that the Supreme Leader’s office issued an edict saying how immoral it is. These are ordinary Iranians, not just the middle and upper class. There has been this massive socio-cultural shift. Generation Z are used to different social norms and strictures and they are not going to be told what to do. They want full autonomy not only over their bodies but over their lives.”

In the intervening years, Iranian people have become even more resourceful than in previous protests.

“This is what 43 years of a repressive and censorious regime have done,” says Navai. “Most Iranians have VPNs [virtual private networks]. There are occasional blackouts – not all VPNs keep working so they have to change them. Iranian exiles are paying for that service, sending login details to Iranians within the country to help them mobilise. They have also been mobilising in quite interesting ways using social media but actually also old-fashioned meet-ups.”

The recent public expressions of protest by leading Iranians, such as the actress Taraneh Alidoosti and a women’s basketball team, are “hugely significant”, she believes.

“They are emboldening the protesters to rise up against the regime,” she says. “I also think these high-profile protests and the world’s media and social media are a really important tool for this uprising. It is the oxygen that is keeping these protests going. Without the world watching I think the regime would be far more brutal. It has already been very brutal. It hasn’t unleashed its might yet and I am scared that it will.”

In many revolutions, it is when the military switches sides, abandoning their loyalty to the leaders under pressure from the people that real change happens. Indeed, some experts have speculated that change will only come to Iran when that happens. However, there are good reasons to think that may not happen.

Iran’s regular armed forces number around 420,000 plus another 300,000 or so who are reservists who can be called up.

What is perhaps stopping them from switching their loyalty is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, set up by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979.

“You have 100,000 to 150,000 soldiers who are the Revolutionary Guard,” says Navai. “It was set up to ensure loyalty to the Supreme Leader and the state and act as a counter-balance to monitor the ordinary forces. These Revolutionary Guardsmen are better trained, far better equipped and are far more loyal – they are ideologically motivated and answer directly to the Supreme Leader. It will be a big turning point if the army turns, however I think that could also result in a bloodbath.”

There are also the Iranian regime’s allies beyond the country’s borders – the Shia militia in Iraq and Hezbollah.

What is clear from Navai’s City of Lies is the widespread hypocrisy of the Iranian regime. It tells stories of clerics using prostitutes and the ubiquity of porn.

“This is one of many reasons that Iranians have had enough,” says Navai. “The regime is not only corrupt politically, it is corrupt morally. While the state enforces laws that govern its citizens’ most intimate affairs meanwhile people in power do as they please. You have people in power whose children are partying in Iran and across the world, doing drugs, wearing whatever they want and having normal sexual relations that are not allowed under the regime. It is this hypocrisy that people are finally fed up with.”

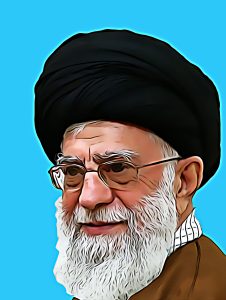

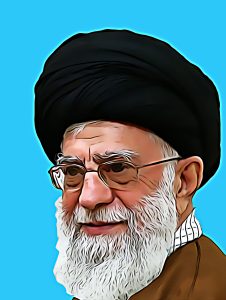

1 Dec 2022 | Iran, Tyrant of the Year 2022

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

“This is a classic from the authoritarian playbook,” says Index’s associate editor Mark Frary. “How often do you see such pro-government rallies in truly free countries? You have to wonder what pressure they bring to bear on the people present to agree to take part in events which are clearly designed to drown out true protests.”

The September rallies were a largely unsuccessful attempt, at least outside Iran, to distract attention from widespread protests in the country following the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, detained by Iran’s notorious Gasht-e Ershad.

“These so-called ‘morality police’ uphold respect for Islamic morals, including detaining women who they see as being improperly dressed, such as wearing revealing or tight-fitting clothing or not wearing the required hijab,” says Frary.

Since then the country has been wracked by protests, which have been violently subdued. Oslo-based NGO Iran Human Rights say that a minimum of 448 people, including 60 children, have been killed in the protests. Many of those paying the ultimate price for protest have been women.

The Iranian authorities have been trying to keep a lid on the news by shutting down the internet in the country. Iran’s parliament has also been working on a draft bill that seeks to impose further restrictions on internet access for people in Iran, including criminalising the use of virtual private networks.