11 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

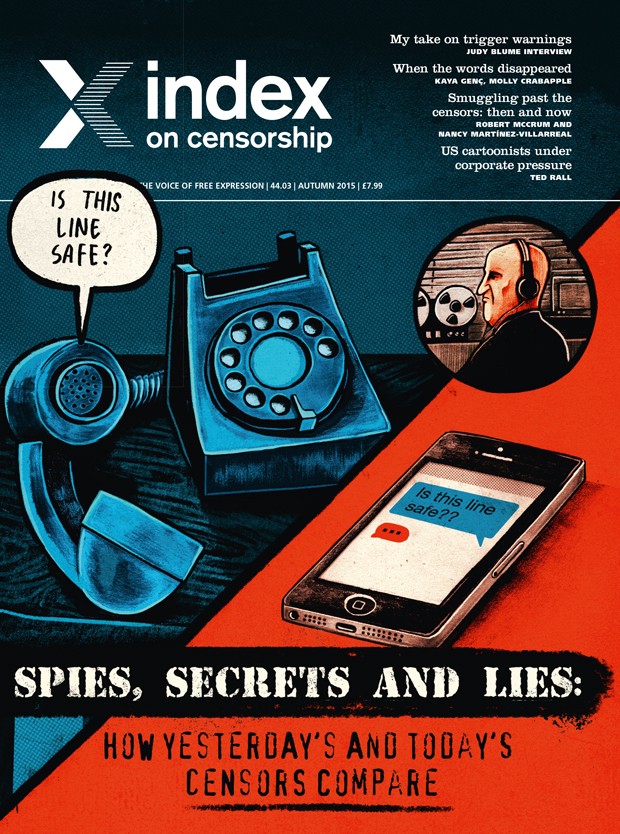

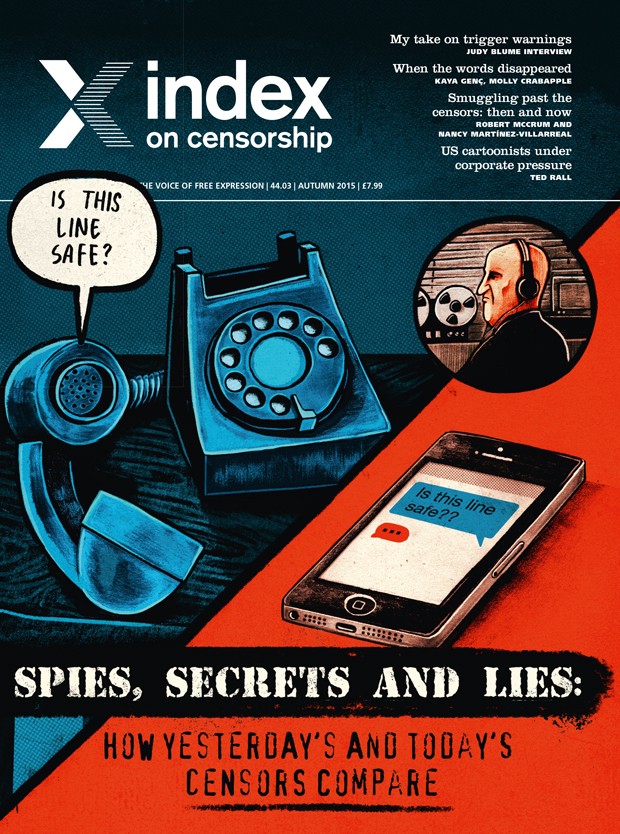

The autumn 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine focuses on comparisons between yesterday’s and today’s censors and will be available from 14 September.

In the latest issue on Index on Censorship magazine Spies, secrets and lies: How yesterday’s and today’s censors compare, we look at nations around the world, from South Korea to Argentina, and discuss if the worst excesses of censorship have passed or whether new techniques and technology make it even more difficult for the public to attain information.

Smuggling documents and writing out of restricted countries has helped get the news out, and into Index on Censorship magazine over the years. In this issue, you can hear three stories of how writing and ideas were smuggled into or out of countries. Robert McCrum swapped bananas for smuggled documents in Communist Czechoslovakia; Nancy Martínez-Villarreal used lipstick containers to hide notes in Pinochet’s Chile and Kim Joon Young tells of how flash drives hidden in car tyres take information into North Korea.

Also in this issue, an interview with Judy Blume on over-protective parents’ stopping children from reading, Molly Crapabble illustrates a new short story from Turkish novelist Kaya Genç, Jamie Bartlett on crypto wars and Iranian satirist Hadi Khorsandi on how writers are muzzled and threatened in Iran. Don’t miss Mark Frary mythbusting the technological tricks that can and can’t protect your privacy from corporations and censors.

There’s also a cartoon strip by award-winning artist Martin Rowson, newly translated Russian poetry and a long extract of a Brazilian play that has never before been translated into English.

CONTENTS: Issue 44, 3

Spies, secrets and lies: How yesterdays and today’s censors compare?

SPECIAL REPORT

New dog, old tricks – Jemimah Steinfeld compares life and censorship in 1980s China with that of today

Smugglers’ tales – Three people who’ve smuggled documents from around the world discuss their experiences

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson’s regular cartoon is a challenge from Chairman Miaow

From murder to bureaucratic mayhem – Andrew Graham-Yooll assesses what happened to Argentina’s journalists after the country’s dictatorship crumbled

Words of warning – Raymond Joseph, a young reporter during apartheid, compares press freedom in South Africa then and now

South Korea’s smartphone spies– Steven Borowiec reports on a new law in South Korea embedding a surveillance tool on teenagers’ phones

“We lost journalism in Russia” – Andrei Aliaksandrau examines the evolution of censorship in Russia from the Soviet era to today

Indian films on the cutting-room floor – Suhrith Parthasarathy discusses the likes and dislikes of India’s film boards over the decades

The books that nobody reads – Iranian satirist Hadi Khorsandi reports on how it is harder than ever for writers in his homeland to evade censorship

Lessons from McCarthyism – Judith Shapiro looks at the impact of the McCarthyite accusations and fasts forward to address the challenges to free speech in the US today

Doxxed – When prominent women express their views online, they can face misogynist abuse. Video game developer Brianna Wu, who was targeted during the Gamergate scandal, gives her view

Reporting rights? – Milana Knezevic looks at threats to journalism in the former Yugoslavia since the Balkan wars

My life on the blacklist – Uzbek writer Mamadali Makhmudov tells Index how his works continue to be suppressed having already served 14 years on bogus jail charges

Global view – F0r her regular column, Index’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg writes about libraries; how they are vital communities and why censorship should be left at their doors

IN FOCUS

Battle of the bans – US author Judy Blume talks to Index’s deputy editor Vicky Baker about trigger warnings, book bannings and children’s literature today

Drawing down – Ted Rall discusses why US cartoonists are being forced to play it safe to keep their shrinking pay cheques

Under the radar – Jamie Bartlett explores how people keep security agencies in check

Mythbusters – Mark Frary debunks some widely held misconceptions and discusses which devices, programs and apps you can trust

Clearing the air: investigating Weibo censorship in China – Academics Matthew Auer and King-Wa Fu discuss new research that reveals the censorship of microbloggers who spoke out after a documentary on air pollution was shown in China

NGOs: under fire, under surveillance – Natasha Joseph looks at how some of South Africa’s civil rights organisations are fearing for the future

“Some words are more powerful than guns” – Alan Leo interviews Nobel Peace Prize nominee Gene Sharp

Taking back the web – Jason DaPonte takes a look at the technology companies putting free speech first

CULTURE

New world (dis)order – A short story by Kaya Genç about words disappearing from the Turkish language, featuring illustrations by Molly Crabapple

Send in the clowns – A darkly comic play by Miraci Deretti, lost during Brazil’s dictatorship, translated into English for the first time

Poetic portraits – Russian poet Marina Boroditskaya introduces a Lev Ozerov poem, never before published in English, translated by Robert Chandler

Index around the world – Max Goldbart rounds up Index’s work and events in the last three months

A matter of facts – For her regular Endnote column, Vicky Baker looks at the rise of fact-checking organisations being used to combat misinformation

Take out a digital annual magazine subscription (4 issues) from anywhere in the world, £18.

Have four stunning print copies delivered to your doorstep (US and UK), £32.

20 Jul 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.02 Summer 2015

Ann Morgan’s self-imposed challenge to read 196 books in a year taught her much about the world of literary censorship. Credit: Steve Lennon

“For as long as people have been telling stories other people have been trying to shut them up,” writes Ann Morgan in Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer. The book, published earlier this year, charts her bid to read a book from each of the world’s 196 independent states. In the 365-day challenge, she faced constant barriers, from trying to find literature in places with almost no publishing industry, such as the Marshall Islands, to tracking down the works that the authorities have tried to hide.

Morgan found herself getting a crash course in world censorship. Two of the exiled writers she profiled have stories featured in the summer 2015 edition of Index on Censorship magazine: Ak Welsapar from Turkmenistan and Hamid Ismailov from Uzbekistan.

It was a chance tweet that Morgan spotted about Welsapar’s poetry that first led her to the as-yet-unpublished translation of his novel, The Tale of Aypi. She was soon struck by his use of Aesopian language and allegory to communicate subversive or challenging ideas, a literary tactic that Welsapar revealed was by no means accidental. Morgan told Index, “Towards the end of the Soviet era there was a relative loophole in one of the censor’s guidance documents that said that if there was an element of doubt in what was meant, the writer had the benefit of the doubt. This was a grey area that was quite freeing for Ak.” However, when the country declared independence in 1991, he found himself more censored than ever before, his works were banned and he was forced to flee to Sweden.

Ismailov faced a similar plight. After working on a series of articles and projects that criticised the Uzbek regime, his books – and even any mention of his name – were forbidden. He fled the country and ended up in the UK, working for the BBC. Morgan said: “When [Ismailov] was growing up, he always thought there was something wrong with the literature he was reading. All the positives he’d been bombarded with in Soviet literature didn’t make sense. He was seeing this gap between his reality and the reality of what he was reading.”

But of the 196 countries Morgan explored on a literary level, North Korea was the one that intrigued her the most. Keen to discover what – if anything – is read within its fiercely guarded border, she contacted a spokesman for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (DPRK) Committee for Cultural Relations for Foreign Countries (run by Alejandro Cao De Benós, the first and only foreigner to be allowed to work for the government in North Korea) and, after much persistence, was eventually sent a manuscript of My Life and Faith, the memoir of jailed North Korean war correspondent Ri In Mo. Mo was imprisoned for 40 years in South Korea in 1950, after being arrested for fighting as a guerrilla during the Korean War. Although his autobiography is primarily used as propaganda, Morgan found his work far less two-dimensional than she had expected; it included thought-provoking passages on how Mo engaged with the South Korean media after his release and how his words were altered by journalists to make him sound “more North Korean”.

Morgan feels her interactions with the DPRK Committee and reading the corresponding work taught her much about our refusal in the west to engage with abhorrent ideas: “I got reactions from people saying you shouldn’t read anything from there [North Korea], but to me this was still censorship, it was quite sinister. How are you to have a dialogue and move forwards if you are banishing them from the realm of the human and not allowing for any common ground?”

So does she believe books such as hers can help bring people’s attention worldwide to the issues surrounding literary censorship and further publicise these semi-forgotten works? “Hopefully, the project has brought attention to the works of a number of those writers who I encountered, and the works of many other writers out there who I didn’t read directly. I hope it encourages readers generally to look further and I hope in the long run it will bring more opportunities for other writers.”

You can read short stories by Ak Welsapar and Hamid Ismailov in the summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Ann Morgan’s book, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer, was published in the UK by Harville Sacker in January 2015. Her blog is A year of reading the world.

15 May 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

Nick Griffin, leader of the British National Party, arrives at a protest in June 2013 in Westminster. (Photo: Paul Smyth / Demotix)

BBC Radio Five Live’s Breakfast yesterday dutifully carried out its public service remit by interviewing Nick Griffin, the world’s most tedious Nazi demagogue, ahead of the European elections. Griffin’s British National Party does have some seats in the European Parliament, so is entitled to some airtime.

It was a dull interview. They always are. The BBC interviewers–in this case, Nicky Campbell–want to pick away at the BNP facade, but always somehow miss out on the really strange stuff. Long ago, I vowed that I would never write about Griffin without pointing out that he had written a pamphlet called “Who Are The Mindbenders?”, which is a catalogue of Jewish and Jewish people who work in the media. Griffin believes that these evil Jews (sorry, “Zionists”) are involved in an enormous plot to keep him–the saviour of the white race–out of the press and off the airwaves.

The conspiracist aspect of BNP policies is often overlooked, with the straightforward racism critiqued more heavily. So it was here. Campbell asked Griffin if he had a problem with black and mixed-race players representing England in the upcoming World Cup. Griffin, barely missing a beat, started complaining about BBC liberals smearing him and worse, denying him airtime.

“The BBC owes me 12 Question Times,” he declared, bemoaning his lack of invitations to appear on the BBC’s Thursday night festival of shouting from and at the telly.

It might have been interesting to delve into why Griffin felt he was being kept off Question Time, to see how long he would be able to maintain a line before going full Doctor Strangelove. As it was, we got only the superficial whine. The whine of the martyr-bully.

It is the background sound of our time. There is absolutely no one engaged in modern public life at any level at all who has not complained that they’ve been silenced, denied a platform, bullied into submission by a cruel cabal of agents of reaction or “the liberal agenda”, take your pick.

That is not to say people are not censored, even in the lovely modern 21st Century. It happens, quite a bit. People get locked up for saying stupid things on the internet that affront public sentiment. For years the libel laws restrained reporters, reviewers and the man on the Clapham Omnibus from saying what they really knew, or thought, or thought they knew. And no reader of this site needs to be told what happens in the less than democratic countries all over the world.

But there is actual censorship, and there is the claim to being censored, which are often two separate things. The BNP’s Griffin, UKIP’s Nigel Farage, and every Blimp all the way to Westminster delights in telling us, at length, the things that nobody, least of all them, is allowed to talk about anymore.

Meanwhile, on the left and the pseudo-left, there is an obsession with “platforms”; who has one, who deserves one, who is denied one. Editors and writers who do their best to represent as many diverse views as possible are denounced routinely for the articles they haven’t published rather than the ones they have. Every oversight is evidence of a conspiracy rather than a cock-up. The right people are always being excluded by the wrong people. If only, if only everyone shut up and let me speak, we think, then I could sort everything out.

It’s ironic that many of those who argue most vehemently that they are being censored are the exact ones who demand everyone else shut up. Intersectional feminists who insist they are being excluded from debate demand that radical feminists be “no platformed”. Ukipers who claim they’re not allowed talk about immigration want the police to arrest their opponents in anti-racist movements. All of them, simultaneously, noisily, will end up invoking Niermoller’s “First they came for…” (with the possible exception of the BNP, who, stopping short of displaying sympathy with Communists or Jews, instead content themselves with calling their opponents “the real fascists”, as I once heard Griffin do at Oxford Union).

Why is this? Why does everyone want to be censored?

It’s possible that the simple reason is that we are constantly improving as a society. Triumphalism and privilege are pretty much taboo for many. On the face of it, most of the people reading this, and certainly the person writing it, are probably the luckiest sons of bitches to ever have walked the earth. But a combination of our still-relevant horror at the great wars of the last century, plus a greater ability to learn about the ideas and experiences of others, make most of us wary of revelling in our role as the victor. Instead, we prefer to be the underdog, because underdogs are more virtuous–victims rather than perpetrators. Martyrs, even.

The Nazis and Communists of the 20th century also believed they were more sinned against than sinning, but the difference was that they were certain they would show the world who was really boss. Now, no one outside the most extreme movements – Al Qaeda; or North Korean Juche – really wants to state that aim openly. We want to remain oppressed. Censorship is considered almost universally as a bad thing, so people on whom it is inflicted are good.

The background whine of censorship, emanating even from the powerful may just be the tiny price we pay for a world that is generally better and kinder.

I think we can live with that.

This article was posted on May 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 May 2014 | News

A London protest calling for the release of jailed Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt (Image: Index on Censorship)

Press freedom is at a decade low. Considering just a handful of the events of the past year — from Russian crackdowns on independent media and imprisoned journalists in Egypt, to press in Ukraine being attacked with impunity and government reactions to reporting on mass surveillance in the UK — it is not surprising that Freedom House have come to this conclusion in the latest edition of their annual press freedom report. This serves as a stark reminder that press freedom is a right we need to work continuously and tirelessly to promote, uphold and protect — both to ensure the safety of journalists and to safeguard our collective right to information and ability to hold those in power to account. On the eve of World Press Freedom day, we look back at some of the threats faced by the world’s press in the last 12 months.

1) Journalism is not terrorism…

National security has been used as an excuse to crack down on the press this year. “Freedom of information is too often sacrificed to an overly broad and abusive interpretation of national security needs, marking a disturbing retreat from democratic practices,” say Reporters Without Borders (RSF) in their recently released 2014 Press Freedom Index.

Journalists have faced terrorism and national security-related accusations in places known for their somewhat chequered relationship with press freedom, including Ethiopia and Egypt. However, the US and the UK, which have long prided themselves on respecting and protecting civil liberties, have also come under criticism for using such tactics — especially in connection to the ongoing revelations of government-sponsored mass surveillance.

American authorities have gone after former NSA contractor and whistleblower Edward Snowden, tapped the phones of Associated Press staff, and demanded that journalists, like James Risen, reveal their sources. British authorities, meanwhile, detained David Miranda under the country’s Terrorism Act. Miranda is the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the journalist who broke the mass surveillance story. Authorities also raided the offices of the Guardian — a paper heavily involved in reporting in the Snowden leaks.

2) …but governments still like putting journalists in prison

The Al Jazeera journalists detained in Egypt on terrorism-related charges was one of the biggest stories on attacks on press freedom this year. However, Mohamed Fahmy, Baher Mohamed, Peter Greste and their colleagues are far from the only journalists who will spend World Press Freedom Day behind bars. The latest prison census from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) put the number of journalists in jail for doing their job at 211 — their second highest figure on record.

In Bahrain, award-winning photographer Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced in March to ten years in prison. In Uzebekistan, Muhammad Bekjanov, editor of opposition paper Erk, is serving a 19-year sentence — which was increased from 15 in 2012, just as he was due to be released. In Turkey, after waiting seven years, Fusün Erdoğan, former general manager of radio station Özgür Radyo, was last November sentenced to life in jail. Just last Friday, Ethiopian authorities arrested prominent political journalist Tesfalem Waldyes and six bloggers and activists.

3) New media is under attack…

As more journalism is being conducted online, blogs, social and other new media are increasingly being targeted in the suppression of press freedom. Almost half of the world’s jailed journalists work for online outlets, according to the CPJ. China — with its massive censorship apparatus — has continued censoring microblogging site Sina Weibo, while also turning its attention to relative newcomer WeChat. In March, it closed down several popular accounts, including that of investigative journalist Luo Changping.

Meanwhile, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has publicly all but declared war on social media, at one point calling it the “worst menace to society”. Twitter played a big role in last summer’s Gezi Park protests, used by journalists and other protesters alike. Only days ago, Turkish journalist Önder Aytaç was jailed, essentially, because of the letter “k” in a Tweet.

Meanwhile Russia has seen a big crackdown on online news outlets, while legislation recently passed in the Duma is targeting blogs and social media.

4) …and independent media continues to struggle

Only one in seven people in the world live in countries with free press. In many parts of the world, mainstream media is either under tight control by the government itself or headed up media moguls with links to those in power, with dissenting voices within news organisation often being pushed out. Brazil, for instance, has been labelled “the country of 30 Berlusconis” because regional media is “weakened by their subordination to the centres of power in the country’s individual states”. At the start of the year, RIA Novosti — known for on occasion challenging Russian authorities — was liquidated and replaced by the more Kremlin-friendly Rossiya Segodnya (Russia Today), while in Montenegro, has seen efforts by the government to cut funding to critical media. This is not even mentioning countries like North Korea and Uzbekistan, languishing near the bottom of press freedom ratings, where independent journalism is all but non-existent.

5) Attacks on journalists often go unpunished

A staggering fact about the attacks on journalists around the world, is how many happen with impunity. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed. Most of the perpetrators of those crimes have not been brought to justice. Attacks can be orchestrated by authorities or by non-state actors, but the lack of adequate responses by those in power “fuels the cycle of violence against news providers,” says RSF. In Mexico, a country notorious for violence against the press, three journalists were murdered in 2013. By last October, the state public prosecutor’s office had yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. Syria, with its ongoing, devastating war, is the deadliest place in the world to be a journalist, while some of the attacks on press during the conflict in Ukraine, have also taken place without perpetrators being held accountable. That attacks in the country appear to be accelerating, CPJ say is “a direct result of the impunity with which previous attacks have taken place”.

This article was published on May 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org