21 Sep 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

Investigative journalist Ivan Ninic knew something was wrong when he saw the two young men reach down. “I saw they were getting two metal bars,” said Ninic, who is the latest victim of violence against journalists in Serbia. Two young men, in tracksuits and baseball caps, assaulted him on a Thursday evening in late August, in Serbia’s capital, Belgrade. “They attacked me and stuck me brutally,” he told UNS, a Serbian association for journalists. “I have a haematoma under my eye, bruises on the thigh bone and an injury to my shoulder.”

Just a week earlier, at a Jazz Festival in the southern city of Nis, local journalist Predrag Blagojevic was beaten by a police officer for — in the words of the officer — “acting smart”. “He grabbed me, bent my arm behind my back and repeated several times ‘Why are you acting smart?’ Then he hit me in the head with his hand. He hit me twice,” Blagojevic stated after the incident. Blagojevic had been approached by the officer and asked for his identity papers. Blagojevic had asked “why?” The police officer took him to his car and started beating him.

Media freedoms in Serbia are on the decline. The country has been cited in 93 verified violations against the media reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project. A recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), painted a picture of journalists in several western Balkan countries, working in hostile environments whilst facing threats and intimidation.

“It’s certainly not going forward,” HRW researcher Lydia Gall said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “What in fact should be showing progress, is rather deteriorating.”

Gall interviewed over 80 journalists in Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The stories she heard were shocking.

“These are all countries that are transitioning,” she said. “They’re undergoing democratic development in, one would hope, a positive direction. But when you look at the documentation I’ve collected you’ll see a worrying picture unravel.”

The report contains examples of threats, beatings, and even the murder of several journalists. It also claims there is political interference, pressure and a lack of action by the authorities to investigate and prosecute those responsible for crimes against the media.

In Serbia alone Human Rights Watch reported 28 cases of physical attacks, threats, and other types of intimidation against journalists between January and August 2014.

NUNS (the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia) has documented a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, and attacks, in the period from 2008 to 2014. This may be the tip of the iceberg since, according to NUNS, many media workers don’t report attacks.

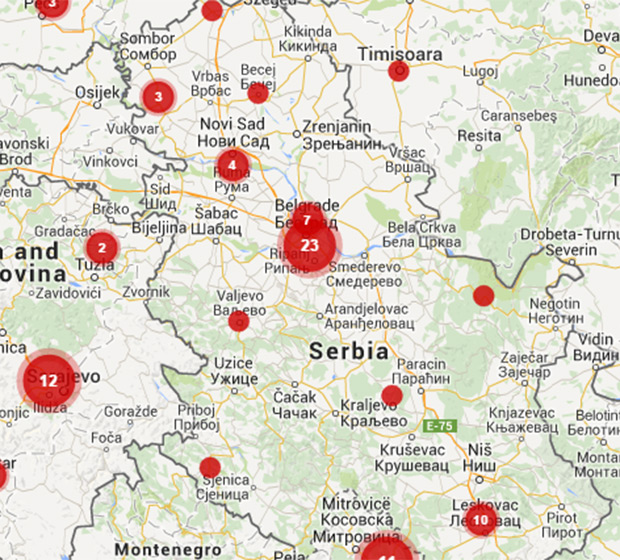

Between May 2014 and June 2015, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project has received 77 reports of violations against Serbian journalists and media workers.

Most of the targeted journalists investigate corruption and allegations of war crimes. Both Ivan Ninic and Predrag Blagojevic report on corruption on a regular basis. “These are not popular topics in the Balkans,” Lydia Gall said. “There are always people in power trying to get them not to write about them.”

Serbia has undergone incredible change over the past two decades. During the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia censorship was directly imposed by the state. Few forget the difficulties of reporting in Serbia during the darkest moments of the 1990s. Means and methods of pressure and censorship are very different nowadays.

“It’s not necessarily the state going after the journalist anymore,” Gall explained. “But it’s more the state neglecting to properly investigate crimes against journalists.”

“If it’s not physical interference or abuse, then it’s threats, or so-called friendly advice. In some cases journalists are being sued for civil libel and end up spending most of their time in courts instead of doing their work. It can be done in very subtle ways.”

This all contributes to a hostile environment for journalists to work in, the HRW report concludes. “You have to be a brave person to do this type of reporting in the Balkans,” said Gall.

Sometimes pressure on the media in Serbia is not even that subtle. Current Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic, has been accused of being overly hostile against the media. He has publicly labeled Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) foreign spies . The current government has also been accused by some journalists of involvement in several cyber attacks on critical online media portals, such as Pescanik.

“Improving media freedom is an important condition in Serbia’s negotiation process with the European Union for membership. But EU’s pressure on Serbia is too weak,” said Gall.

“They’re mainly looking at the legislative framework. On paper it looks great. The problem comes to light when you look on the ground. When you speak to journalists, who are living this reality every day.”

Meanwhile the Serbian journalist associations, NUNS and UNS, are trying to put pressure on the authorities to track down the attackers of Ivan Ninic.

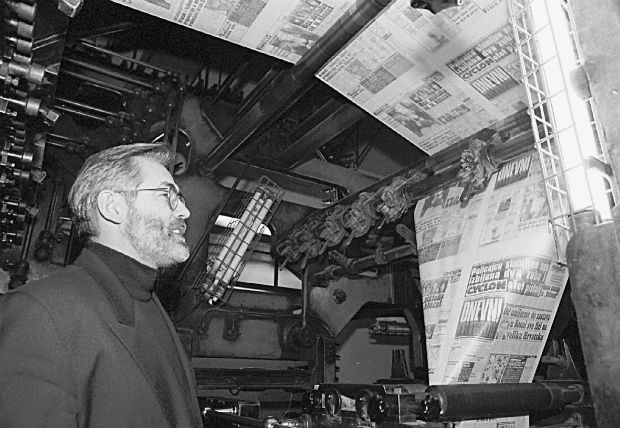

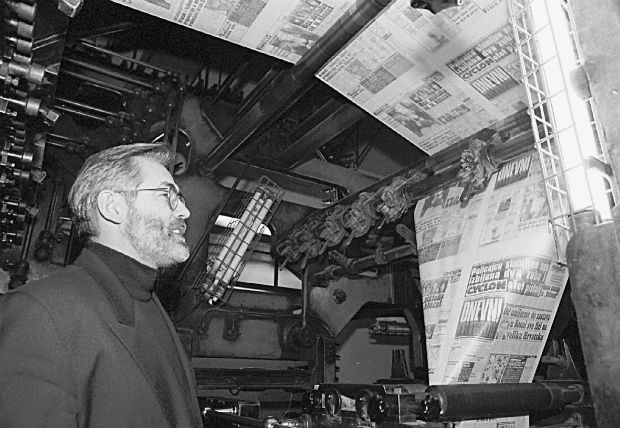

Ninic is known for his investigations into corruption within high levels of government. He founded the Center for the Rule of Law, an NGO, and is planning to launch a website to publish investigative reports.

He believes the attack is a warning: “I expect the police will find and punish not only the attackers, but also the masterminds, so that I know who is sending me this message,” he said in a statement.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was published on 16 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

Journalist Slavko Curuvija, murdered in Belgrade in 1999 (Photo: Predrag Mitic)

As NATO bombs were falling on the Serbian capital Belgrade on 11 April 1999 , a man was being executed on a side street in the centre of the city. The victim was later identified as Slavko Curuvija, a prominent Serbian anti-regime journalist. A post mortem found that Curuvija had been shot in the back 17 times. Five days earlier the state-run daily Politika Ekspres had published an article calling Curuvija a traitor and a NATO supporter.

Fast forward to 1 June 2015: the trial of four former security officers begins before a special court in Belgrade. It took 16 years for anyone to stand trial over what had become a notorious case of intimidation of journalists in Serbia.

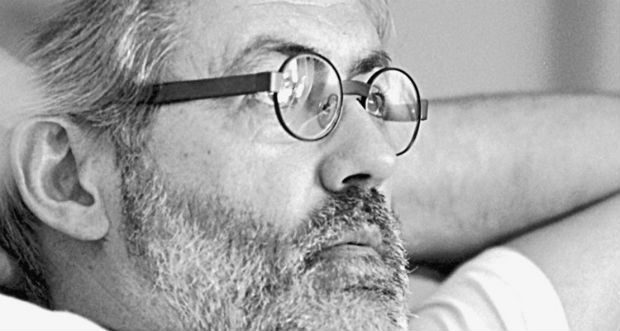

Much of the credit for pursuing a cause by many considered lost can go to veteran journalist Veran Matic, the editor-in-chief of media group B92.

Several Serbian governments had shown no signs that they were willing to solve Curuvija’s case; the same goes for many other war-time murders. For years, Matic and his fellow journalists would mark the anniversary of Curuvija’s death by laying flowers at Svetogorska Street, where he lived and died, and by raising awareness in the media and with the government. It was not enough.

In 2013, Matic was fed up with waiting for answers about the murders of his colleagues. He proposed to form a special body to investigate the killings of Curuvija and two other journalists. Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic — then deputy prime minister — gave Matic permission to form the Commission for Investigating Killings of Journalists in Serbia. It was an unexpected move. As Curuvija was being executed on a Belgrade side street, Vucic was minister of information in President Slobodan Milosevic’s government.

“Some criticised the establishment of the commission for giving an opportunity to Vucic to clear his past,” says Matic, referring to the unease many journalists felt towards Vucic, who was highly critical towards independent media during the nineties.

“Marking every year the anniversary of the killing, visiting the place of assault, criticising the state again and again for failing to resolve those crimes became very humiliating for me,” Matic said. “In this way, I have been given another instrument through which I could do something in practice.”

It was clear that Matic needed the government’s cooperation if he wanted the murders to be solved. “I wanted to get hold of every single document and, in order to do this, we needed a commission that would be supported by the government,” he said. But Matic managed to ensure the body was made up of three representatives of the independent media, three members of the ministry of internal affairs and three representatives of the security information agency. With Matic himself serving as the commission’s chairman, journalists will always be in the majority.

Progress and challenges

(Photo: Predrag Mitic)

The commission is focusing on three big murder cases from the recent past. The work around Curuvija’s case has been the most successful until now, with four people charged. Trials for former Chief of State Security Rade Markovic and the two ex-secret service officers Ratko Romic and Milan Radonjic began 1 June. The fourth accused is Miroslav Kurak, also a former state security member and the man who is believed to have pulled the trigger on Curuvija. He is being tried in absentia, as he is still at large, an Interpol warrant issued for his arrest. There are clues that Kurak is living in Central or South Africa where he owns a hunting safari agency.

The Dada Vujasinovic case is perhaps the most difficult, as the murder took place over two decades ago. Vujasinovic was a reporter for the news magazine Duga and wrote about Zeljko Raznatovic, also known as Arkan. She was found dead in her apartment in 1994. The police ruled it a suicide, but most evidence disputes this. When the commission started working on the case, there were doubts about the forensic research done in Serbia at the time. “I decided that the first step would be to seek expertise outside of the country, as the trust in domestic institutions had been compromised,” said Matic. “We asked the Dutch National Forensic Institute based in The Hague, who offered to perform the forensic examinations for 35,000 euro. We are now raising funds for this, given that the prosecutor’s office has no budget for these services.”

The third case is that of Milan Pantic, who was murdered in June 2001 while entering his apartment building in the central Serbian town of Jagodina. Attackers broke his neck, and was also struck on the head with a sharp object. Pantic worked for the newspaper Vecernje Novosti, where he reported on criminal affairs and corruption in local companies. Prior to the killing, he had received numerous telephone threats in response to articles he had written. It’s not an easy task to investigate. “We know that one of the suspects is living in Germany under a different name,” explained Matic. “But we didn’t get permission to conduct an interview with him.”

The commission is also looking into the deaths of 16 media staffers from RTS — Serbia’s state broadcaster — who were killed during a NATO airstrike targeting its headquarters in 1999. “This is a very complex issue,” said Matic. “The executioner is certainly a pilot of one of the NATO member countries. The people who decided to put a media company on the list of war targets should face trial, as well as those who issued the order to launch missiles and kill the media workers. And also the people responsible in Serbia, who knew the building would be bombed and did not evacuate it.” NATO is refusing to cooperate in this case.

Unique commission

It is of great importance, Matic believes, that these cold cases will be solved. “Unpunished crimes, especially this committed by state institutions, only call for new violence, threats and endangerment of the safety of journalists. It leaves deep scars in the lives of journalists in this country and it contributes to censorship and fear.”

A commission like this is unique in the world; a government body controlled by independent media representatives. And its first success, the arrests in the Curuvija murder case, was surprising to many who’d lost faith in the justice system in Serbia. “This commission was not established by politicians. On the contrary, they accepted all my requests and ideas,” said Matic. “This is quite an atypical commission that works on making results, and none of its members have any political or other motives, but solely finding the killers and masterminds that hide behind the killings, and bringing them to justice.”

Jailing the head of Serbia’s secret service during the nineties, a dark period for both the country and its internal security apparatus, has come with a high price. Matic now lives under 24/7 police protection and he can’t travel anywhere without a police escort. “Some names have again been brought to light, along with their disgraceful role [in the killings]. Some are threatened with arrest, while some of them have been arrested already,” he said of the ongoing investigation.

Matic receives threats often, mostly via email, some of them to his life. But he has gotten used to having police officers in front of his door at all times because, he said, the truth is worth the compromise.

“This is the price we have to pay in order to resolve those crimes,” he said. “It will contribute to the catharsis of our society.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

An earlier version of this article stated that Aleksandar Vucic was interior minister when the commission was set up. This has been corrected.

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Mar 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

Working as a professional journalist in Serbia is hard. Being one in the country’s inland is even harder. Out of the 58 verified incidents involving Serbian media outlets and professionals reported to Index on Censorship’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom, 30 have occurred outside Belgrade; the country’s political, economic and media capital. Four of these incidents have been directed at Juzne Vesti staff.

Launched in 2010 by journalist Predrag Blagojevic, Juzne Vesti is an independent news site based in Nis, a town of 257.000 in southern Serbia. In just over five years, its journalists have been subjected to verbal harassment or death threats 15 times. Though they have reported the incidents to local authorities, it has not resulted in convictions.

“Nobody has been found guilty and punished for the threats,” Blagojevic, who is also the site’s editor-in-chief, told Index.

According to Blagojevic, the main obstacle to punishing those threatening journalists comes from the prosecutor’s office. While he is quick to complement police in the town for their professional and timely investigations, he blames prosecutors for failing to act on the evidence by filing indictments quickly.

“In two situations from four to six months passed from the time the police filed a criminal charge to the prosecutor’s indictments,” Blagojevic explained.

Juzne Vesti correspondent Dragan Marinkovic from Leskovac received threats on Facebook after he published an article about the death of a woman, in which he questioned the treatment provided by a paramedic. He reported the incident to authorities. Several months later prosecutors decided not to pursue the case, arguing that “you deserve a bullet” is not a threat.

In March 2014 Blagojevic was threatened by the owner of a local football club, yet prosecutors waited until late September to indict the main suspect. The first court hearing was scheduled for December 2014; the next one at the end of this month.

While such delays are frustrating, once in court, judges have taken some dubious positions, Blagojevic said. In one case, the court said that “be careful what you write” or “do not play with fire” were not threats, but words that “merely showed the seriousness of the topic”. In another instance, where the perpetrator asked a Juzne Vesti staffer “Will you be alive in the morning if you wrote something like this in the USA?”, the court said that “the inductee, by placing the action in the foreign country, shows that he is aware that murder is prohibited by Serbian law”.

Outside the legal system, there is another obstacle to independent journalism in Serbia: money. While the Serbian government pays for advertising space, most of the earmarked money is directed at the national press. At the same time, the number of successful companies outside Belgrade and Novi Sad are few, and those that do thrive in the Serbian inland are usually aligned with local political figures. That leaves a tiny pool of advertisers.

“In these circumstances we are left with only very small companies, which are connected with political parties or dependent on municipal budgets. The game is straightforward — only if you are good to us you will get money,” Blagojevic said.

In an interview with SEEMO, Blagojevic described situations where certain media outlets have been financed with taxpayers’ money. With this line of funding, competing outlets are able to offer low rates that distort the advertising market, which puts pressure on independent media to drop their rates.

“The local government in Nis sets aside hundreds of millions of dinars in payment for these PR services,” Blagojevic said. The money is sometimes up to 80 per cent of the budget for these outlets making it even more difficult for independent media to compete.

The Council of Europe’s recent report on the Serbian media situation addressed the issue: “Instead of making efforts to create non-discriminatory conditions for media industry development, the state is blatantly undermining free market competition.”

The last issue confronting Juzne Vesti staff is one that will be familiar to small town journalists around the world — everyone knows everyone. Blagojevic tells of having to convince one journalist to file a complaint because she knew the person who had targeted her. She was reluctant because she had known the person “since they were kids”, he said.

From Blagojevic’s point of view, the toxic mix of money, political pressure and indifference from the courts causes self-censorship among journalists.

“The language from the 90s is back in Serbia. Again, journalists that criticise the work of the government or are reporting on corruption are labelled as foreign mercenaries. Threats like this come from the mouths of the highest state representatives,” he said.

An earlier version of this article stated that Nis has a population of 184,000. The latest census puts the figure at 257.000.

This article was posted on March 27, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Serbia

Around 1 am on Thursday 3 July 2014, Davor Pasalic, editor of Serbian news agency FoNet, was brutally assaulted as he made his way home from the office. Pasalic, who had stopped for pizza, was accosted by three young men who demanded money and told him they had a gun. Pasalic refused and the men began beating him while shouting nationality-based slurs. Pasalic estimates that they struck him about 30 times before leaving him alone. The injured man then crossed a bridge leading to his apartment and was again attacked by the three men. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises to his head and body. Four of his teeth were broken or knocked out.

“I have no clue why those three guys attacked me,” Pasalic told Index on Censorship. “One of the guys asked me: Are you a Croat? I was born in Belgrade. I have no accent. I look like every other citizen of Belgrade. Nobody has ever asked me that question before. How did he figure out that I am ethnic Croat?”

Six months have elapsed since the brutal assault, but police have made no progress in unmasking the culprits or discovering their motives. Nebojsa Stefanovic, Serbian minister of internal affairs, insists authorities are handling the incident as a priority, while Pasalic has said he is not certain whether police are unwilling or unable to resolve the assault. Journalists’ associations in Serbia are worried, vowing they “won’t allow” the beating to become just another case in the long line of unresolved attacks on media workers in Serbia.

From 2008 to 2014, Serbian has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidations and attacks on property of media professionals, according to a report by the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS). The numbers should be taken as provisional, it added, since many media workers do not report attacks. The real figure is likely higher than the official one. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom has received 48 reports of violations against Serbian media including attacks to property and intimidation and physical violence, one of which was the attack on Pasalic.

“In the period between 2008 and 2011 less than 10 per cent of all attacks were processed,” NUNS said. “We also have problems with the judicial process, even in cases where the identity of the aggressor is very obvious. In Serbian courts it is common for attackers to receive minimum sentences, which obviously encourages attacks,” said NUNS’ President Vukasin Obradovic in a statement. He believes this situation leads to self-censorship within the country’s press.

Media freedom violations are also covered in the annual reports on human rights in Serbia by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights (BCHR). In 2013 they reported, among other things, that hand grenades had been thrown at the home of the owner of the website Telegraf and that four journalists were under 24 hour police protection. In 2012 they pointed out, pointed out that despite a high number of attacks on the media, trials of press workers progressed faster than trials of perpetrators of attacks on journalists: “Minister Velimir Ilic was at long last found guilty and fined almost 1.4 million RSD for physically assaulting a journalist of the Novi Sad TV Apolo back in 2003. The assailant on TV B92 cameraman in 2008 was sentenced to one year in jail in 2012. The men who threatened to kill the author of the B92 show Insider Brankica Stankovic in 2009 were sentenced to 16 months’ imprisonment and six-month and one-year conditional sentences respectively.”

BCHR noted in its 2011 report that some court judgments confirmed the suspicion that perpetrators who attack journalists can count on lenient sentences. In 2010, they found that journalists were mostly being attacked by politicians, policemen and local businessmen dissatisfied with their reporting, and that — like in the previous years — most of the perpetrators went unpunished.

There are also cases where law enforcement authorities appear to simply not be doing their jobs, according to lawyer Kruna Savovic, who is part of the NUNS legal team. Speaking to Radio Free Europe, she shared the story of a journalist who reported death threats against him and his mother to the police. He stated the identity of the suspect, named witnesses and filed a report, but instead of processing the case, officers told him he would be charged if he continued to bother them.

The attacks on Pasalic were not captured by surveillance cameras in the area, and according to Stefanovic’s statement, the lack of video is complicating the investigation. The minister also asserted that a report was not filed on the night of the incident. Pasalic refutes that, saying he had sought medical treatment at the military medical academy after the assaults and told the on-duty officers what had occurred.

Serbian journalists’ associations have been unified in condemning the incident. “Serbian society is burdened with numerous attacks on journalists which remain unsolved and their perpetrators unpunished, sometimes for decades. This encourages the attackers and contributes to spreading fear and insecurity both among journalists and the society as a whole,” the Association of Independent Electronic Media (ANEM) pointed out.

The international community has also taken note. “Journalists’ safety is a key issue in the OSCE region. There must be no impunity for crimes committed against media workers”, said OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic, and in its 2014 progress report on Serbia, the European Commission stressed that threats and violence against journalists “still remain a concern”. The Commission and other international non-governmental organisations urged Serbian authorities to keep their promised to investigate the killings of journalists Radislava Dada Vulasinovic in 1994, Slavko Curuvija in 1999 and Milan Pantic in 2001, as well as other attacks.

So far a Serbian special commission, which was created in 2013 and tasked with reopening the unresolved murders of journalists has achieved progress in the case of Curuvija. The commission found information that connects four former state security officials with the killing. They were all charged. Three of them were imprisoned while “one of the indicted men is believed to be on the run and living in an African country”. In 2014, NUNS reported, there was only one journalist under 24 hour police protection.

After six months of investigation and zero progress Pasalic ironically says that his case is “no big deal.” But, he said that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Veteran B92 journalist Veran Matic has worked against impunity and to bring murders of Vulasinovic, Curuvija and Pantic to justice. “The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship,” he told Index last November. But he added: “In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way.”

Recent reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Serbia: Prime minister calls BIRN’s journalists “liars”

Serbia: Journalist fired after demotion

Serbia: “Doctors” send death threats after report

Serbia: Mayor criticised for implying journalists not welcome

Serbia: Journalist demoted after publishing report

This article was posted on 12 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org