26 Sep 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News, Politics and Society

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

“States must stop trying to define who is and isn’t a journalist. The media landscape has changed irreversibly,” said Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, as she opened the organisation’s Open Journalism event in Vienna on Friday, 19 Sept.

Journalism – wherever you draw its boundaries – has more voices than ever, but are all they all being properly recognised and safeguarded? This was one of the main problems addressed by the expert panel, which included Index on Censorship, alongside delegates from Azerbaijan, Serbia, Estonia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and many other OSCE member states.

Gill Phillips, the Guardian’s director of editorial legal services, spoke via pre-recorded video about difficulties in defining journalism and deciding who gets journalistic protection. She cited the Snowden scoop, which was led by Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer, and later embroiled his partner, David Miranda. Who gets the protection? Greenwald? Miranda? Lead staff reporter David Leigh? All three?

There was widespread condemnation of Russia’s new law, which compels bloggers with more than 3,000 views per day to be registered with the authorities. “[The bloggers] have certain privileges and obligations,” said Irina Levova, from the Russian Association of Electronic Communications, who repeatedly defended the law. “Online and offline rights are not the same,” she said, adding that some of those who deemed the law a mode of censorship have been revealed as “foreign agents”.

Another topic – raised repeatedly by various attendees – was Russian media’s growing influence over citizens in nearby countries. Begaim Usenova of the Media Policy Institute in Kyrgyzstan said: “The common view being spread from the Russian media is that the United States is starting world war three and only Putin can stop him.”

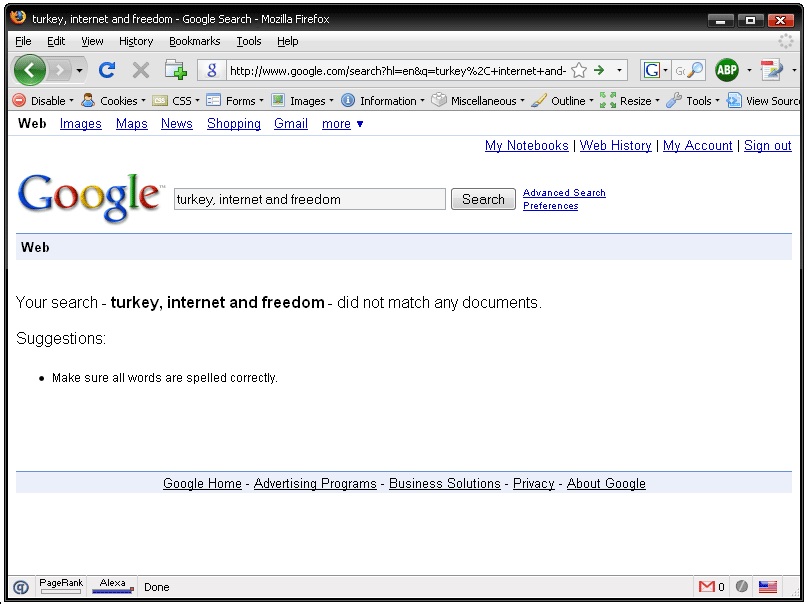

Yaman Akdeniz, a Turkish cyber-rights activist, shared news of Twitter accounts that remain blocked in his country, including some with over 500,000 followers. Igor Loskutov, a business director from Kazakhstan, looked back on the first 20 years of internet in his country and how authorities have gone from ignoring their first rudimentary websites to now wanting complete control.

The thorny issue of “public interest” was also discussed. Jose Alberto Azeredo Lopes, professor of International Law at the Catholic University of Porto, raised some smiles with his theory: “It’s like pornography. You can’t define it. But you know it when you see it.”

As the day-long discussions wrapped up, one delegate asked: if a blogger’s first-ever post goes viral, are they immediately subject to the same laws as the press? Especially in countries that now insist bloggers register.

The debate over the difference between journalists and bloggers went round in circles – as it always does – but the OSCE is hoping to be able to compile all the findings from its expert meetings into an online resource to move the discussion forward.

Azeredo Lopes concluded: “If you don’t distinguish freedom of expression from freedom of the press, you end up with no journalists, and that is the crisis that journalism faces today.”

Read our interview with Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media, in the autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, coming soon

This article was published on Friday September 26 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Jun 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, Russia

@AndreiSoldatov and @cyberrights at the @IndexCensorship Brussels event on Press Freedom in Russia Turkey Azerbaijan. Photo: Ricardo Gutiérrez

On Thursday, Index hosted a discussion with five leading media experts from Turkey, Russia, and Azerbaijan. As journalists, bloggers, entrepreneurs and campaigners, they experience first-hand how censorship – online and off – is being ramped up in their countries, and they argue that their stories are still not being sufficiently heard.

Turkey’s Yaman Akdeniz and Amberin Zaman, Russia’s Andrei Soldatov and Anton Nossik, and Azeri blogger Arzu Geybulla shared shocking stories about journalists harassed in government-led smear campaigns, the arrests on spurious criminal charges of those who speak openly on social media, and the growing role of governments in blocking free expression online.

“The internet is becoming less and less independent of government interference,” Nossik told the Brussels audience.

Index works with writers – including authors, journalists and bloggers – and artists globally to help them tell a wider world about the threats they face. We are a platform that allows individuals to speak for themselves, and fights for those who cannot.

In the first article from one of our event speakers, Andrei Soldatov assesses the state of online freedom in Russia:

Since November 2012, we’ve been living in a country with the internet censored extensively by a nationwide system of filtering.

This system has been constantly updated ever since. Now we have four official blacklists of banned websites and pages: the first one is to deal with sites deemed extremist; the second is about sites blocked because of child pornography, suicide and drugs; the third consists of sites with copyright problems; the fourth, the most recent one, was created in February and lists the sites blocked without a court order because they call for non-sanctioned protests. There is also an unofficial fifth blacklist aimed not at sites but at hosting companies, based abroad, which have proven themselves not very cooperative with Russian authorities.

Technically, the internet filtering system in Russia is not very sophisticated. Thousands of sites were blocked by mistake, while if you want to access a blocked site you can do that using circumvention tools or even very basic things like Google translate.

At the same time very few people were sent to jail for posting critical things online, and relatively few new media were put under direct government pressure.

But surprisingly, freedom of expression on the internet in Russia has been hugely affected: users have become cautious in their comments, and internet companies, the largest in the country, even when invited to talk to Putin, are so frightened that they failed to raise the issue of regulation at the meeting.

The beauty of the Russian approach is that it doesn’t need to be technically sophisticated to be efficient. It also doesn’t need mass repression against journalists or activists.

So why is that?

Basically, the Russian approach is all about instigating self-censorship. To do this, you need to draft the legislation as broad as possible, to have the restrictions constantly expanded — like the recent law which requires bloggers with more than 3.000 followers to be registered — and companies, internet service providers, NGOs and media will rush to you to be consulted and told what’s allowed. You should also show that you don’t hesitate to block entire services like YouTube – and companies will come to you suggesting technical solutions, as happened with DPI (deep packet inspection). It helps the government to shift the task of developing a technical solution to business, as well as costs.

You also need to encourage pro-government activists to attack the most vocal critics, to launch websites with list of so-called national traitors, and then to have Vladimir Putin himself to use this very term in a speech.

All that sends a very strong message. And as a result, journalists will be fired for critical reporting from Ukraine by media owners, not by the government; the largest internet companies will seek private meetings with Putin, and users of social networks will become more cautious in their comments.

We have seen this before – the very same approach was used against traditional media in the 2000s. What made the situation on the internet special is that the government found a way to shift the task of providing a technical solution for censorship to companies, including the global ones, and make the companies pay for the system. The way global platforms seem to respond to that is not very impressive. Localisation cannot be a solution because it helps to localise the problems of censorship. Now the Russian search engine Yandex presents two different maps of Ukraine, with and without Crimea, for the Ukrainian and Russian audiences respectively.

The biggest problem with this approach is that it provokes governments to put more pressure on global platforms. One day Twitter was heavily criticised by a Russian official in a pro-Kremlin paper who threatened to block the platform completely. The next day Twitter rushed to block an account of Pravy Sector, one of the most-anti Russian political parties in Ukraine, and blocked it for Russian users.

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan News, Events, News

(Photo: Kusadasi-Guy via Creative Commons)

“Whenever we’ll have to choose between excessive regulation and protection of online freedom, we’ll definitely opt for freedom” Vladimir Putin, 1999

Since Putin said this, 3 days before becoming President, history has marched on…

“We will make arrangements without limiting and restricting freedom, but also without bowing to threats and without ignoring the dangers. We will hand over Turkey to generations who are not slaves to technology, but who rule and direct technology” Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, 2014

Terrorised twitter users, blackmailed bloggers and intimidated independent media, digital freedom has been facing a crack-down in Russia, Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Index on Censorship are bringing some of these countries foremost journalists and digital freedom advocates to Brussels to discuss events in their countries, to debate what the EU could do to help and to consider what we ourselves could learn from these experiences?

As we approach several major summits on internet governance, how can the EU tackle the growing risk of fragmentation, avoid calls for forced local hosting and stand up to the top-down approach favoured by the Russians?

“Is it because I was free that I was warned that I was going to lose my column if I would not stop criticizing the government? Is it because I was free that I was fired when I turned a deaf ear to warnings?” Amberin Zaman

The discussion, moderated by new Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg, will include:

- Andrei Soldatov – Investigative Journalist, Founder Agentura.ru. @AndreiSoldatov

- Anton Nossik – Blogger and Founding Editor-In-Chief of leading news websites inc. Gazeta.Ru, Lenta.Ru, Vesti.Ru, NTV.Ru (now NewsRu.com). @dolboed

- Dr Yaman Akdeniz – renowned advocate and Professor of Law, Istanbul Bilgi University, Founder and Director of Cyber-Rights.Org. @cyberrights

- Amberin Zaman – Censored former columnist at Haberturk, current journalist at Taraf and Turkey correspondent for The Economist.

- Arzu Geybulla – Azerbaijani Blogger, based in Istanbul. @arzugeybulla

WHEN: 5pm CET, Thursday 19 June 2014

WHERE: Google, Chaussée d’Etterbeek 180, Bruxelles, Belgium

TICKETS: Free but space limited – RSVP to [email protected]

Follow the discussion live @IndexEvents – #beatingretreat