2 Jul 2025 | Iran, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Newsletters

As I wrote the newsletter last week we were closely following events in Iran but didn’t have a full picture in terms of free speech ramifications, in part because of censorship itself – internet blackouts and media bans meant that information was slow to leave the country. One week on, it’s different. Many alarming stories have emerged.

The conflict between Israel and Iran was of course marked from the start by free speech violations – early on there was the bombing of Iranian state television. Then later there were strikes on Tehran’s Evin Prison. While these acts may have been intended as symbolic blows against key institutions of Iranian repression, the consequences were grimly real: media workers killed, political prisoners endangered. And in between? Lots of repression.

At Index, some developments were personal, including when our 2023 Arts Award winner – the rapper Toomaj Salehi – disappeared for three days. Beyond our immediate network, according to the Centre for Human Rights in Iran, more than 700 citizens have been arrested in the past 12 days, some for alleged “espionage” or “collaboration” with Israel. There have also been six executions on espionage charges carried out, with additional death sentences expected.

The Supreme Council of National Security announced that any action deemed supportive of Israel would be met with the most severe penalty: death. The scope was broad, ranging from “legitimising the Zionist regime” to “spreading false information” or “sowing division”.

As mentioned above, Iran also began restricting internet access before shutting down access altogether. Officials claimed the blackout was necessary to disrupt Israeli drone operations allegedly controlled through local SIM-based networks. The result: ordinary Iranians were cut off from vital news. International journalists from outfits like Deutsche Welle (DW) were banned from reporting inside Iran. The family of a UK-based journalist with Iran International TV was even detained in Tehran, in an attempt to force her resignation. Her father called her under duress, parroting instructions from security agents: “I’ve told you a thousand times to resign. What other consequences do you expect?”

Yet amid the bleakness, there have been a few positive instances. Iranian state media aired a patriotic song by Moein, a pop icon long exiled in Los Angeles. Some billboards replaced religious slogans with pre-Islamic imagery, such as the mythical figure Arash the Archer. There has also been an unexpected digital reprieve: on Wednesday, following the agreement of an Israel-Iran ceasefire deal brokered by the US administration the day before, Iranians reported unfiltered access to Instagram and WhatsApp for the first time in two years.

Given everything else it feels unlikely that this openness will last. This week’s proposals by Iran’s judiciary officials to expand espionage laws and increase the powers of Iran’s sprawling security apparatus imply as much, too. So while the world’s eyes might have moved away from Iran, our gaze is still there – documenting the free speech violations and campaigning for their end.

9 May 2025

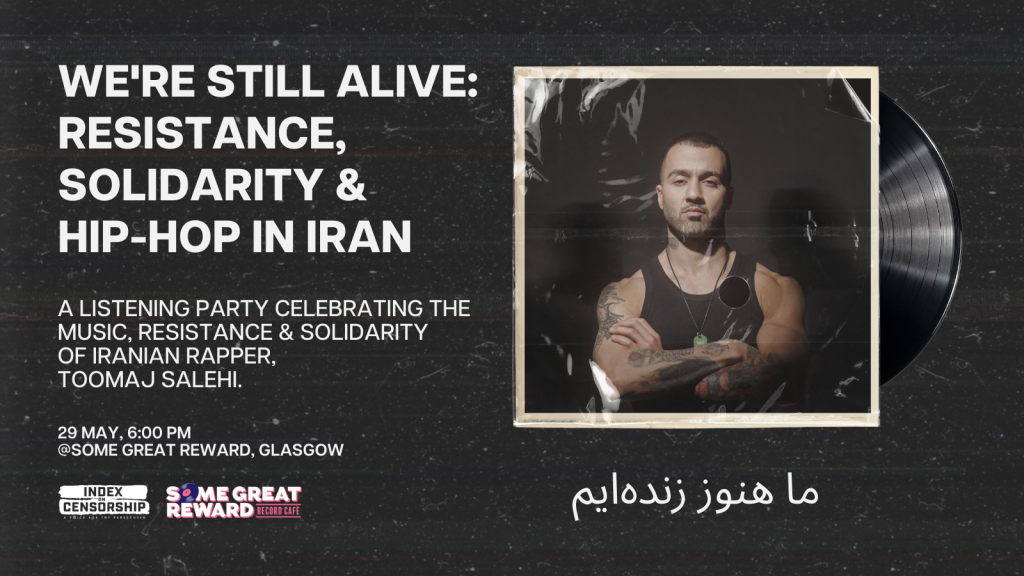

Join Index on Censorship and Some Great Reward for a Listening Party celebrating the music, resistance and solidarity of Iranian rapper, Toomaj Salehi.

Toomaj is a Farsi-language rapper who has never shied away from using his music to stand up for those raising their voices calling for human rights and democracy in Iran. For his courage and music, he has long been persecuted by the Iranian regime – facing harassment, surveillance, imprisonment and a death sentence as a result.

Toomaj has been persecuted for his music so there is no more powerful way to stand in solidarity with him than to celebrate his music. That is why we are inviting music fans to come together on the southside of Glasgow to share his songs, learn about his life and stand in solidarity with him and everyone in Iran standing up for human rights and democracy. This is not a ticketed event – just turn up.

About Toomaj Salehi’s persecution

Over the last four years, Toomaj has faced continuous judicial harassment, including arrest and imprisonment. He has been more intensely targeted following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody September 2022, when he became a vocal supporter of the Women, Life, Freedom movement. After publishing songs in support of the courageous protesters and taking part in the protest himself he was arrested and sentenced to over 6 years in prison. On 18 November 2023, Toomaj was released on bail. But his freedom was not to last.

Days later he was rearrested after he uploaded a video to YouTube documenting his treatment and torture while in detention. In April 2024, an Iranian court sentenced him to death on charges of “corruption on earth”. It took the Supreme Court to intervene to quash the death sentence, leading to Toomaj being released from prison in December 2024.

14 Mar 2025 | Iran, Statements

On 13 March 2025, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (“UNWGAD”) issued an opinion declaring that Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi’s detention of more than 753 days was arbitrary and in violation of international law. A joint petition was submitted to the UNWGAD by the Human Rights Foundation, Doughty Street Chambers, and Index on Censorship in July 2024.

Mr Salehi has been subjected to a sustained campaign of judicial harassment by Iranian authorities, which has included periods of imprisonment, arrest, torture, and a death sentence. His treatment was the result of his music and activism in supporting protest movements across Iran.

Mr Salehi was first arrested in October 2022, after he released a song supporting the protests that followed Mahsa Amini’s death in custody. After an extended period of pre-trial detention, including significant time spent in solitary confinement, Mr Salehi was sentenced to six years and three months’ imprisonment for charges including “corruption on earth”, as well as being banned from leaving Iran for two years.

Mr Salehi was temporarily released in November 2023 but was rearrested only 12 days later, after posting a video detailing the torture he endured. In April 2024, he was sentenced to death. His death sentence was overturned by Iran’s Supreme Court in June 2024. Shortly after, two further cases were filed against Mr Salehi based on his new song, Typhus. In December 2024, Mr Salehi was released from prison, although the two most recent cases remain on foot.

In its opinion, the UNWGAD found that there was a clear pattern of discrimination against Mr Salehi on the basis of his political opinions and as an artist expressing dissent. The UNWGAD said that “ultimately, the song, social media posts, and video were forms of Salehi’s exercise of his freedom of expression”, and concluded that he had been targeted primarily for these forms of speech. The UNWGAD had particular regard to the vague and overly broad “corruption on earth” charge, observing that none of Mr Salehi’s alleged crimes fall under it.

The UNWGAD’s opinion also noted that Mr Salehi wasn’t tried by a public or independent court and was given limited access to his lawyer. Even when he was able to contact his lawyer, the calls were monitored. The UNWGAD expressed grave concern about the torture that Mr Salehi endured during his detention and the brief period of enforced disappearance, and indicated particular concern about the use of torture to compel a confession.

In response to the opinion, Mr Salehi’s cousin, Arezou Eghbali Babadi, said:

“What is happening under the Iranian regime against those who stand for their rights is a direct assault on human dignity and justice. Those in power manipulate the system to silence voices of truth, leaving individuals defenseless. With no safeguards, no accountability, and no limits to their violence, every moment is uncertain. This is not just about Toomaj but it is about a nation’s struggle against fear. This cruelty can be inflicted for something as simple as singing a song or sharing a post. There is an urgent need for the world to stand against tyranny. This opinion by the UNWGAD is an important step towards that goal.”

Nik Williams, campaigns and policy officer at Index on Censorship said:

“For years, Toomaj has faced persecution for his music, activism and solidarity with the courageous women of Iran and everyone standing up for human rights in the country. We welcome this opinion from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, which is an important and timely reminder of the need for continued international support and pressure to ensure he remains free and able to continue his music.”

Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC, international counsel for Mr Salehi’s family, Index on Censorship, and the Human Rights Foundation, said:

“Our brave, brilliant client, Toomaj Salehi, stood firm as Iranian authorities targeted him – with arrests, 753 days’ imprisonment, torture, and a death sentence – and fearlessly maintained his basic right to express himself through his art. His has been an important voice in the push by Iranian people for recognition of their human rights.

Now the UN Working Group’s Opinion confirms the unlawfulness of Mr Salehi’s treatment. It underscores the need to ensure that Mr Salehi remains free, and is not again subjected to arbitrary and unjust treatment by the State. It is a welcome and timely reminder for Iranian authorities that they will be held to account for their actions.”

Claudia Bennett, legal and programme officer at Human Rights Foundation said:

“The UNWGAD’s decision is not just a victory for Toomaj but for all prisoners of conscience in Iran. His case exemplifies the Iranian regime’s intolerance of any criticism, even in the form of art. This decision highlights the alarming reality that a simple song can lead to an absurd charge like ‘corruption on earth’ in Iran, a crime punishable by death. With this decision, the Iranian regime must understand that if it continues to deprive Iranian citizens of their most basic rights and freedoms, the international community will hold it accountable.”

Any press queries for Index on Censorship should be directed to Nik Williams on [email protected].

More background about Toomaj Salehi is available on social media, at @OfficialToomaj (X) and @ToomajOfficial (Instagram). More details of the campaign can be found at #FreeToomaj.

6 Mar 2025 | Iran, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

The beauty and power of Iran’s music is being strangled, with many musicians jailed and tortured purely for raising their voices against the regime’s viciousness and in harmony with those protesting against it.

The case of rapper and Index Freedom of Expression award-winner Toomaj Salehi has been the highest profile case of Iran cracking down on freedom of expression among the country’s musicians but he is not alone. Index was at the heart of the campaign to get Salehi’s sentence commuted and he was eventually released but the country’s other musicians still face persecution.

Musicians like Salehi are regularly thrown in jail for highlighting the brutality and hypocrisy of Iran’s government. Even after release from prison, if they are lucky, these musicians still face surveillance and control.

Singer Mehdi Yarrahi, whose song Roosarito (Your Headscarf) gained widespread attention and became an anthem of resistance, was jailed in early 2024 for challenging “the morals and customs of Islamic society”. After his release on medical grounds, he was forced to wear an ankle tag to track his movements. A source told Index that this has only recently been removed. This week, it was reported that Yarrahi had been sentenced to the inhumane torture of 74 lashes to end the criminal case against him.

In May last year, rappers Vafa Ahmadpour and Danial Moghaddam were sentenced to prison for “propaganda against the regime”. Our source tells us they are serving their sentences under house arrest and must wear ankle tags to restrict movement away from their homes.

These sentences and treatment, for simply writing songs of protest, are unjust.

Another recent case involves musician and activist Khosrow Azarbeig who was arrested in Tehran on 17 February for “insulting” former Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad following a protest performance in Tehran’s metro.

The lawyer Amir Raesian shared the news on X: “Mr. Khosrow Azarbeig, a daf player, was arrested on Monday evening on a street in Tehran. His family has been informed that his charge is ‘insulting Bashar al-Assad’.”

It follows a string of other actions against musicians and singers in the country.

Last July, Zara Esmaeili was arrested by Iranian security forces at her home in Karaj. Her arrest came after online footage emerged of her on the streets of Tehran singing the Amy Winehouse hit Back To Black without wearing a hijab.

According to a friend, just one day before her arrest, she tried to prevent the security police from detaining one of her friends in Tehran. This escalated into a confrontation with security forces, ultimately resulting in her violent arrest.

The exiled Iranian filmmaker Vahid Zarezadeh, now in Germany, told Index: “Zara Esmaeili was not widely known in the media, which meant that her voice remained largely unheard. She has been in detention for several months now, yet her family has received no information about her whereabouts or the reason for her arrest – a scenario all too familiar for many detainees in Iran.”

“Since then, there has been no official information about the charges against her, her legal status, or even where she is being held. Meanwhile, her Instagram account was suspended by order of the Iranian judiciary – a common tactic used to silence activists and dissidents.”

He added: “Our best assumption is that she is being held in solitary confinement in Ward 209 of Evin Prison, as no one inside the prison has seen or heard from her. Her situation remains shrouded in uncertainty, and, like many others, the complete silence surrounding her case could indicate that she is under severe pressure in detention.”

In December, the singer Parastoo Ahmadi was arrested along with two band members for performing a livestream concert in the symbolic venue of an old caravanserai (an inn which provided lodging for travellers) without wearing a hijab, violating Iran’s strict rules on dress for women.

Posting the concert on her channel, she wrote: “I am Parastoo, a girl who wants to sing for the people I love. This is a right I could not ignore; singing for the land I love passionately. Here, in this part of our beloved Iran, where history and our myths intertwine, hear my voice in this imaginary concert and imagine this beautiful homeland… I am grateful to all those who have supported me in these difficult and special circumstances.”

The other members arrested were Iranian composer Ehsan Beyraghdar and guitarist Soheil Faghih Nasiri.

The Iranian authorities issued a statement saying that the concert took place “without legal authorisation and adherence to Sharia principles” and that appropriate action would be taken against the singer and production team. Since it was posted, the video has attracted 2.5 million views and was widely shared on Iranian social media, despite YouTube being banned in the country.

Ahmadi and the others have since been released on bail pending a trial.

Meanwhile, the controversial Iranian rapper Amir Hossein Maghsoudloo (better known as Amir Tataloo) is facing up to 15 years in prison.

The singer, known for being completely covered in tattoos, fled to Istanbul, Turkey in 2018 following repeated arrests by the Iranian authorities. In December 2023, he was deported by Turkish authorities, seemingly for visa violations although some reports say that his return to Iran was of his own volition. On crossing into Iran at the Bazargan border crossing, he was arrested.

While he was in Turkey, controversy swirled around Tataloo including allegations of attempts to groom young girls.

In 2020, Tataloo’s Instagram profile was suspended after he was accused of inviting young girls to join his “harem”. He later allegedly posted an audio file on Telegram justifying his position in which he said: “What I discussed was legitimate by the laws of our country and our religion. It is in our religion that you can have… four wives and 40 concubines. Also, marriage above the age of nine is allowed in Islam. But I said 15 to 16 years of age. Then I said with the consent of the parents, so that there would be no controversy.”

Since his return to Iran, he has been sentenced to 10 years in prison for “promoting corruption and prostitution”, a sentence upheld by the Court of Appeal. He faces a further five years for “insulting religious sanctities” but this is currently under review by the Supreme Court.

Some reports have claimed that Tataloo has been sentenced to death for blasphemy against the Prophet (“Sabb al-Nabi”). However, the Iranian judiciary’s media centre has denied this, stating that his final sentence has not yet been issued.

“Many individuals and social groups hesitate to support him due to his unpredictable character,” said Zarezadeh. “His supporters and critics alike constantly anticipate his next move – one day he performs a concert on the deck of an Iranian military vessel, another day he poses alongside President Ebrahim Raisi, and then at another moment, he positions himself as an opposition figure. All of these contradictions have made his case even more ambiguous.”

Despite the controversy surrounding Tataloo and his alleged crimes, the fact is that Iran has a problem with the freedom of expression of its musicians. Music was never intended to be silenced but heard. This systemic persecution has to stop.