2 May 2019 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Serbia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”106589″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Every Saturday, for the past five months, thousands of people have gathered on the streets of Serbian capital Belgrade to voice their dissent against President Aleksandar Vučić’s authoritarian tendencies and increasing control over the country’s media.

“Initially the protests were named ‘Stop the Bloody Shirts’,” Serbian journalist Lazara Marinkovic said. “And this was a reaction to an incident that happened in one city in Serbia, where Borko Stefanaović, an opposition leader, was physically beaten.”

Stefanaović, who was attacked last November in Kruševac, is the president of the political party Serbian Left and a founder of opposition coalition Alliance for Serbia. His assault, in which a masked group of assailants armed with bats and steel bars beat him, led to a rally in Belgrade.

“These people were saying that the beating happened as a result of political violence that the opposition is exposed to,” continued Marinkovic. “After one or two weeks, our president vucic had a reaction to those protests. He said ‘even if five million people were on the streets, (he) wouldn’t concede to their demands.’”

This sparked the formation of protests dubbed “one in five million” – a name lifted directly from Vučić’s comment. Though it remains uncertain whether the ongoing rallies will bring about change, Mitra Nazar, a Balkans correspondent for Dutch public broadcaster NOS, says it is “important” for protesters to demonstrate their unhappiness with Vučić.

“At this moment it’s about showing presence in the street more than actually having the feeling that they could change something,” said Nazar, who currently lives in Belgrade.

“I don’t think anybody in these protests believes that this could turn around now, but they do see this as part of a bigger movement that could eventually grow into something substantial, that could challenge the ruling party at elections.”

The demonstrations are the biggest since the fall of former President Slobodan Milosevic in 2000 – though lack of coverage in mainstream Serbian media would suggest otherwise. With Vučić pushing for Serbia to join the European Union, his grip on the media has tightened in efforts to appear stable to Brussels.

“Vučić wants to be the person that brings Serbia into the EU,” continued Nazar, “and in Brussels Vučić is still seen as a leader who can guarantee stability in the Balkans, and someone who’s willing to negotiate about a solution for the frozen conflict in Kosovo.

“His critics say the EU does not pressure Vučić enough on topics like media freedom, whilst they see his control over the media getting stronger.”

The country’s public broadcaster RTS has been targeted by demonstrators who are critical of the outlet’s coverage of the protests. The opposition says that, although reporting is completely neutral, it fails to ask why such a huge amount of people gather outside its headquarters in Belgrade every week.

“They are being biased,” added Marinkovic. “There was an incident when people who were demonstrating went inside the (RTS) building.

“They say that they didn’t go inside violently but some violence did happen because there was a lot of police who started kicking them out. Many people will agree that if these people do something violent, or vandalise something, it would be immediately used against them.

“They are trapped in a way they cannot really radicalise their protest. Nobody listens, nobody cares. It’s just like an echo chamber basically.”[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556799282299-4d20cd01-70c2-7″ taxonomies=”7370, 113″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Apr 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

The 17 March 2016 cover of Informer featured a photograph of Stevan Dojcinovic, editor-in-chief of the Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), with accusations that he was part of a “mafia” trying to bring down the Serbian government.

The front page of Serbian tabloid Informer stands out from the other newspapers displayed at Belgrade’s countless cigarette kiosks. Its red and yellow coloured headlines scream in block capitals at everyone who passes by.

It is the word “Mafija” that attracts most attention on the morning of 17 March 2016. It’s printed on the front page, as is a blurry photo of a journalist. The journalist, Stevan Dojcinovic, is editor-in-chief at Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK). The headline translates: “Mafia is planning attack on family Vucic.” According to Informer, Dojcinovic and his colleagues at KRIK are the mafia and want to bring down the government of Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic.

Psychological attacks on KRIK by the tabloid have happened so often that this was hardly surprising. KRIK has become well known throughout Serbia, not because of its investigative reporting, but because of the attention from Informer.

Informer was founded in 2012 and its editorial coverage has been called “pro-regime oriented” by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, a German political foundation. The paper’s editor-in-chief, Dragan Vucicevic, is said to be a close friend of the prime minister’s.

Since its launch in July 2015, KRIK has published a series of revealing stories about corruption and misuse of office by several high-profile government officials. And ever since, KRIK has been targeted by Informer: KRIK journalists have been called foreign spies trying to bring down the government; they have been accused of spreading lies; they have been personally discredited on Informer’s front pages.

It began on 7 September 2015. KRIK published leaked footage showing one of the biggest drug lords of the Balkans meeting with Ministry of Police officials, including Ivica Dacic, a former prime minister. The video was posted on the KRIK website and caused immediate controversy. A day after the revelation, Informer published an article stating that KRIK was involved with opposition parties and that Dojcinovic is a “Western spy” backed by US embassy staff.

On 19 October KRIK published a thorough investigation into Belgrade’s mayor Sinisa Mali, who allegedly owns offshore companies dealing with selling apartments at the Bulgarian coast.

Exposing Mali, who is a political ally of Vucic’s, soon sparked a new round of allegations by Informer.

Early November 2015 Informer claimed that KRIK, as well as two other independent media organisations BIRN and CINS, were given foreign grants for publications of “false affairs against people close to the government”. Informer’s Vucicevic said on national broadcaster TV Pink, in a special 4-hour-long programme called “Bringing down Vucic”, that the media organisations were planning a step-by-step plot to bring down the government.

Serbia’s journalist unions condemned what they called a smear or lynch campaign. The chairman of the Independent Journalists Association of Serbia (NUNS), Vukasin Obradovic, said that Informer created “an atmosphere of fear and lynching in the society, which may have serious consequences for the personal safety of the journalists involved”.

But the investigative journalists from KRIK were not scared off. They were, in fact, working on their next investigation into another government official: the minister of health, Zdravko Loncar.

KRIK found out that Loncar had been involved with Serbia’s most notorious criminal gang known as the “Zemun clan” when he was still an unknown doctor working at an emergency ward back in 2002. He allegedly had received a free apartment as a reward for “finishing off” a severely wounded gang member by “injecting him with a fatal cocktail”.

KRIK published the full story on February 22. A day later Dojcinovic’s photo was featured on the Informer’s front page again. The article stated that KRIK’s editor-in-chief was “launching false scandals” and was “intentionally creating chaos in the country”. Health minister Loncar was invited to talk on TV Pink, where he did not respond to the allegations but instead accused KRIK of not paying taxes.

Up to that point KRIK had investigated cases of corruption involving high-profile state officials in Vucic’s inner circle. But what everybody was waiting for was an investigation into Vucic himself.

Then came March 18 2016. Informer once again published a photo of KRIK’s Dojcinovic on its front page. But this time it was different.

The tabloid revealed a story KRIK had not yet published about Vucic’s large real estate assets in Belgrade, which he is supposedly hiding under the names of family members.

Informer exposed details of an investigation by KRIK that they could not have obtained in an ordinary manner. According to KRIK, the Informer appears to have relied on information that could only have been gathered through secret service surveillance techniques including physically following journalists and phone tapping.

“For about a year Informer has been attacking us regularly,” Dojcinovic told Index on Censorship. “This is the first time we are being attacked before we even publish the story. Now they are using information from state intelligence agency to discredit us. I don’t care about a smear campaign, they can’t destroy my credibility with a smear campaign. But now the state is after us.”

Currently KRIK is still working on finishing their newest investigation, which is indeed about Vucic’s real estate assets. But meanwhile Dojcinovic fears for the fate of his sources.

“We’ve now seen that they know exactly who we are meeting with. There is pressure on our sources, most of them work in state institutions. Some have already been fired,” Dojcinovic said.

This article was originally posted at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jan 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

It was a Wednesday morning in early November when investigative journalist Slobodan Georgijev opened Informer, one of Serbia’s notorious tabloids. He had just arrived at his office, the newsroom of Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), one of Serbia’s few independent media outlets. When he turned the page he was shocked by what he saw; a picture of his own face amongst two others, in an article calling three media outlets known for critical reporting of the Serbian government, including BIRN, “foreign spies”.

“It was funny and unpleasant at the same time,” Georgijev recalled, speaking to Index on Censorship. “Funny because I knew that this is just a campaign by Informer to undermine the credibility of independent journalists.” More importantly, he had begun worry about his own safety. “It’s also unpleasant because you never know how people will interpret such defamations.”

Several independent media houses — including BIRN, as well as Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) and Center for Investigative Journalism Serbia (CINS) — have alleged that pro-government tabloids like Informer are running a smear campaign against them.

The first major incident followed the publication of a story about the cancellation of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s vacation in August 2015. Informer published an article saying that Vucic was forced to cancel his two day vacation in Serbia due to reporters from BIRN and CINS allegedly booking a room next to his.

The same newspaper also wrote that BIRN and CINS were meeting with European Union representatives on a weekly basis to plan to bring down the government.

“We are basically accused of being financed by the EU to work against our government,” Branko Cecen, director of CINS, told Index on Censorship. Cecen, like Georgiev, was also pictured and called a foreign spy in Informer. “Expressions like ‘foreign mercenaries’ and ‘joint criminal activity against their own state’ have been used.”

Informer newspaper is openly affiliated with the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) of prime minister Aleksandar Vucic and has frequently been accused of political bias in favour of the party and the prime minister.

CINS, KRIK and BIRN have long reported on what they see as a slew of regular negative articles about themselves in tabloid newspapers with close ties to the government. There is no doubt that the three news outlets are targets because of their critical reporting on the government.

One of BIRN’s stories revealed a contract the Serbian government had signed with the national carrier of United Arab Emirates, Etihad Airways, to take over it’s state-owned counterpart Air Serbia. The deal had been financially damaging for Serbia, which was kept from the public until BIRN obtained and published the contract.

Another story investigated alleged corruption concerning a project for pumping out a flooded coal mine. BIRN found out that Serbia’s state-owned power company had awarded a contract to dewater the mine to a company who’s director is a close friend of the prime minister.

The coal mine revelations led to an angry speech about BIRN by Vucic on national television saying: “Tell those liars that they have lied again(.”

He also attacked the EU delegation in Serbia for being involved in discrediting the government by financing BIRN. “They got the money from Davenport and the EU to speak against the Serbian government,” the prime minister said, naming Michael Davenport, the head of the EU delegation in Belgrade.

BIRN’s editor-in-chief Gordana Igric told Index on Censorship she sees a resemblance to Serbia’s difficult nineties. “This reminds me of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic, a time when the prime minister also had a prominent role and critical journalists and NGOs were marked as foreign mercenaries,” she said. “What’s happening in Serbia today makes you feel sad and confused.”

Independent journalists find the path that the prime minister is taking alarming. Some compare him with the Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan or the Russia’s Vladimir Putin. According to Cecen, the level of freedom of expression is at the lowest level since the time of strongman Milosevic. “There is an aggressive campaign against anybody and anything criticising the prime minister and his policies”, he said. “The prime minister has taken over most media in Serbia, especially national TV networks, but also local ones. His small army of social media commentators is terrorising the internet. It is quite bleak and frustrating.”

Regardless of Vucic’s verbal attacks towards the EU delegation, Serbia has opened the first two chapters in its EU membership negotiation in December 2015. This represents a big step towards eventual membership of the European Union. But the latest progress report on Serbia (November 2015) says the country needs to do much more in terms of fighting corruption, the independence of the judiciary and ensuring media freedom.

“The concern over freedom of expression is always expressed in these reports,” Cecen said. “But we see no influence of such reports since situation with media and freedom of expression is deteriorating daily.” Cecen is disappointed in the European Union’s support for independent media in Serbia and finds that EU officials show too much support for the Serbian government and the prime minister.

After he had seen his own face in the paper, Georgiev picked up the phone and called up Informer’s editor-in-chief Dragan Vučićević to ask for a better picture in the next paper. Georgiev jokes about it and clearly doesn’t let accusations and threats hold him back. “People around me are making jokes”, he said. “They call me a foreign mercenary, an enemy of the state.”

Georgiev pressed charges for defamation against Informer. “We are living in a state of constant emergency,” he continued, concerned about the state of press freedom in his country. “Serbia is not like Turkey. But it goes very fast in that direction.”

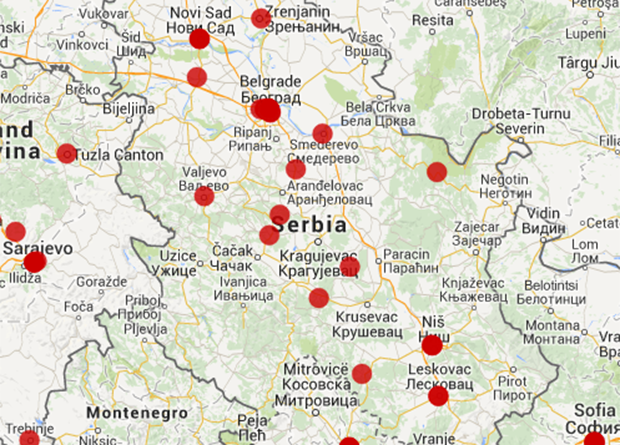

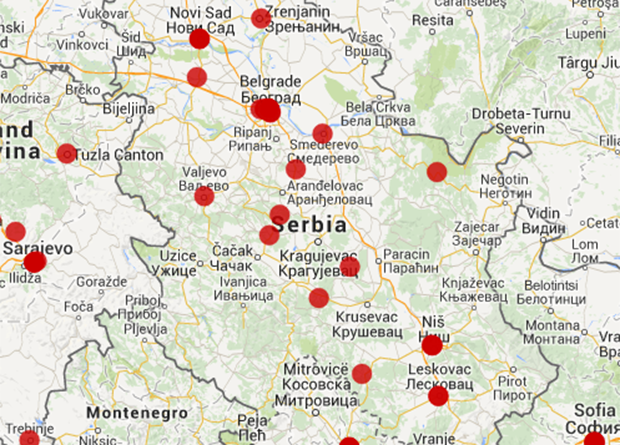

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

29 Oct 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Serbia

Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic speaking at LSE (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

It wasn’t quite a remote controlled drone carrying a provocative political message, but Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s Monday night lecture at the London School of Economics (LSE) came with its own controversial incident.

“What can you say about the total censorship of all opposition media”, Vucic was asked by a young woman in the audience just as the premier sat down for the question and answer portion of the event. She explained that she was representing Nikola Sandulovic, an opposition politician from the Serbian Republican Party, who was sitting beside her. Sandulovic said later he had travelled to London to confront Vucic.

Chaos ensued. Sandulovic claimed, among other things, that a police officer connected to Vucic had threatened to kill him and that he had evidence contained on a CD he held aloft. Vucic hit back that the Republican Party had only 0.01% of public support, and disputed Sandulovic’s assertion that he had been an adviser to former Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic, who was assassinated in 2003. Accusations flew across the room until LSE’s moderator James Ker-Lindsay finally managed regain control of the situation.

After the event, Sandulovic told Index he came to London because the media in Serbia ignore him and his party, apart from when government-friendly outlets attack him.

That press freedom was a popular topic on the night did not comes as a surprise. Serbia has seen a string of censorship incidents during Vucic’s time in power, as Index and many others have reported.

The prime minister himself brought up the press in his introductory lecture. He explained how his government has passed several new laws aimed at improving the media landscape, and complained that despite this, they are “scapegoated”. He directly addressed the recent controversial cancellation of a political talk show, Utisak Nedelje (Impressions of the Week), saying authorities have been subjected to a blame campaign for what was a commercial decision. Supporters of the show, including host Olja Beckovic, say it was down to political pressure.

In a joking reference to his infamous role under Slobodan Milosevic, he said he had been the “worst minister of information”. Curiously, he also used this former job as a counterargument to critics, arguing that his past had made it easy to blame him for any instance of censorship.

But this didn’t seem to stop the press-related questions, though none of the journalists present were chosen to ask one. Apart from the memorable Sandulovic intervention, an audience-member pointed out that Utisak Nedelje wasn’t the only show to have been taken off air in recent times.

If there was an overarching theme to the night, it was that it seemed to showcase different — some would say conflicting — sides of Vucic and his administration. He reminded the audience that Belgrade had recently organised a successful Pride parade, before adding that he didn’t want to attend. To have that choice, he argued, was a real mark of freedom.

There were, of course, questions about the football drone. While Vucic said he didn’t want to share his own views, he said UEFA (European football’s governing body) saw Serbia’s side of the story by awarding them the win, before pointing out that Serbia carries its share of the responsibility. The planned state visit from Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama — the first in 68 years — will go ahead, he also confirmed, despite the post-drone postponement.

In response to questions about relations with Russia — just weeks after the Belgrade military parade where Vladimir Putin was the guest of honour — he said the two countries would continue to build their relationship, but that this would have no impact on Serbia’s ultimate goal of European Union accession.

Much has been made of Vucic’s apparent journey from Milosevic man to EU enthusiast. He seemed to reference this as he said he is “not perfect” and that he works “every single day” to change and better himself. But on Monday, he left more questions than answers about the direction he is taking Serbia in.

Mapping Media Violations in Europe: Serbia

Five media outlets targeted with DDoS attacks

Protesters criticise cancellation of political talk shows

Deputy mayor fined for insulting journalist

Macedonian journalist released from extradition detention

Photographer injured by anti-pride parade protesters

This article was originally posted on 29 October at indexoncensorship.org