Some of our favourite banned books

Monday was the beginning of Banned Books Week, the annual celebration of the freedom to read and have access to information. Since the launch of Banned Books Week in 1982, over 11,300 books have been challenged, according to the American Library Association. To mark the occasion, Index on Censorship staff posed with their favourite banned books, and tell why it’s important that they are freely accessible.

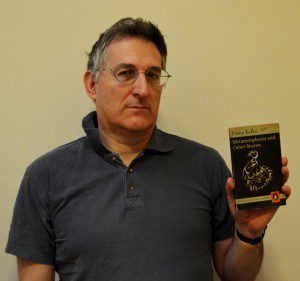

David Sewell – Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“Banned by the Soviet Union for being decadent and despairing and although they’re right in their analysis, the action to ban the book clearly is ludicrous. It’s a Freudian tale of Gregor Samsa who awakes one morning to find he has turned into a human sized bug and how his family react to this turn of events and treat him with revulsion and yes despair, since their main breadwinner is now out of commission. For a book about an insect grubbing about in filth, Kafka’s writing evinces some great beauty as did all his work despite the seam of despair underpinning many of them. Maybe this beauty through despair is what the Soviets meant by ‘decadent’. Kafka was a vital link between the end of the Victorian novel and the literary modernists and the influence of Freud’s ideas increasingly being used in characterisation. That is why ‘Metamorphosis’ is a significant book in the literary canon.”

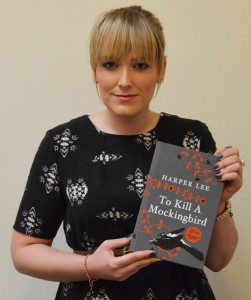

Aimée Hamilton – To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

“Because of its use of profanities, racial slurs and graphically described scenes surrounding sensitive issues like rape, Harper Lee’s award winning novel has been banned in many libraries and schools in the United States over its 54 year history. Having read this beautifully written book at school, I think it should be a freely accessible curriculum staple, to be both enjoyed and admired by all.”

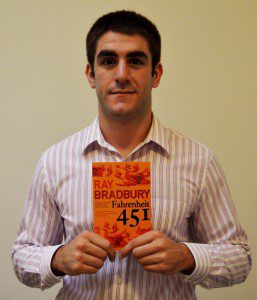

David Coscia – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

“Failing to or not choosing to see the irony, many schools in the United States banned Fahrenheit 451 based on its offensive language and graphic content. Bradbury’s grim view of a future where firemen are not people who put out fires, but instead set them in an attempt to burn books outlawed by the government, acts as a warning against state sponsored censorship, even if it’s not what he intended. Bradbury himself talks about Fahrenheit as a warning that technology would replace literature and cause humanity to become a “quick reading people.” What resonates with me about the novel is how prophetic that turned out to be. In the age of social media and instant information, humans, myself included, have gotten lazy and spend less time enjoying literature.”

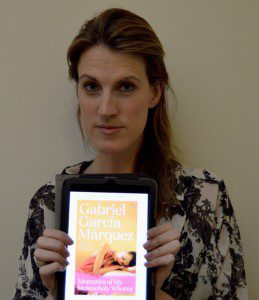

Vicky Baker – Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez:

“I picked this after reading how it was banned in Iran in 2007. Initially, it slipped through the censors’ net, as the Persian title had been changed to Memories of My Melancholy Sweethearts. It was on its way to becoming a bestseller before the ‘mistake’ was realised and it was whipped from shelves, accused of promoting prostitution. It’s classic tale of censors judging a book by its title.”

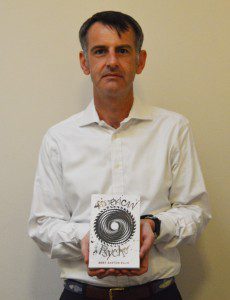

Sean Gallagher – American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

“No book, no matter how vilified or disliked, should be out of reach for anyone who wants to read it.”

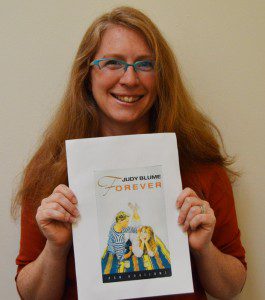

Jodie Ginsberg – Forever by Judy Blume

“I was one of the first girls in my class to own Judy Blume’s Forever and it was passed clandestinely from classmate to classmate until it finally fell apart, dog-eared (and highlighted in certain places…). It is a book that is powerfully linked in my mind – as for so many young kids – to the transition from childhood into the tricky years of teenage life. Reading it felt shocking, even dangerous. But also liberating.”

David Heinemann – Animal Farm by George Orwell

“It seems to have upset people from all ends of the political spectrum in one way or another at different times but what I love is that the story is actually quite ambiguous if you read it carefully, tearing pieces out of everyone and all angles. For its extraordinary imaginative power, the sheer audacity of its metaphors and it’s sharp alertness to the truths of life I treasure this book, having read it and been reminded of it so many times. I even adapted and staged the thing once, banning it is like depriving life of liquor.”

Fiona Bradley – Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“I have chosen Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov because I think it is so deeply disturbing that it deserves to be read. It manages to convey some of the darkest human desires and emotions and these are exactly the kind of things that literature and art should explore. By banning it you are not protecting people but patronising them by refusing their right to judge it for themselves.”

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org