7 Sep 2018 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

After Bulgarian news reporter Maria Dimitrova helped expose an organised crime group from Vratsa’s involvement in fraud and drug trafficking, she received threatening text and Facebook messages. One of the gang’s victims, who spoke to Dimitrova for her report, was later attacked by three unidentified men. According to investigative journalism outlet Bivol, investigators from the Vratsa police precinct, where Dimitrova was questioned, “acted cynically and with disparagement”.

In November 2017, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform, which monitors press freedom violations in 43 countries, revealed that members of the gang had planned to murder Georgi Ezekiev, the publisher of the Zov News, where Dimitrova works/had worked.

Zoltan Sipos, MMF’s Bulgaria correspondent, says such violations have had a marked impact on the country’s media, adding that “sophisticated” soft censorship is a “big problem”.

“Self-censorship is also an issue in Bulgaria, though the nature of this form of censorship is that its existence is difficult to prove unless journalists come forward with their experiences,” he says.

Under increasing pressure from the government and a media environment becoming more and more censored, journalists within Bulgaria are finding themselves in danger. With an inadequate legal framework, pressure from editors and other limitations, journalists regularly self-censor or suffer the consequences.

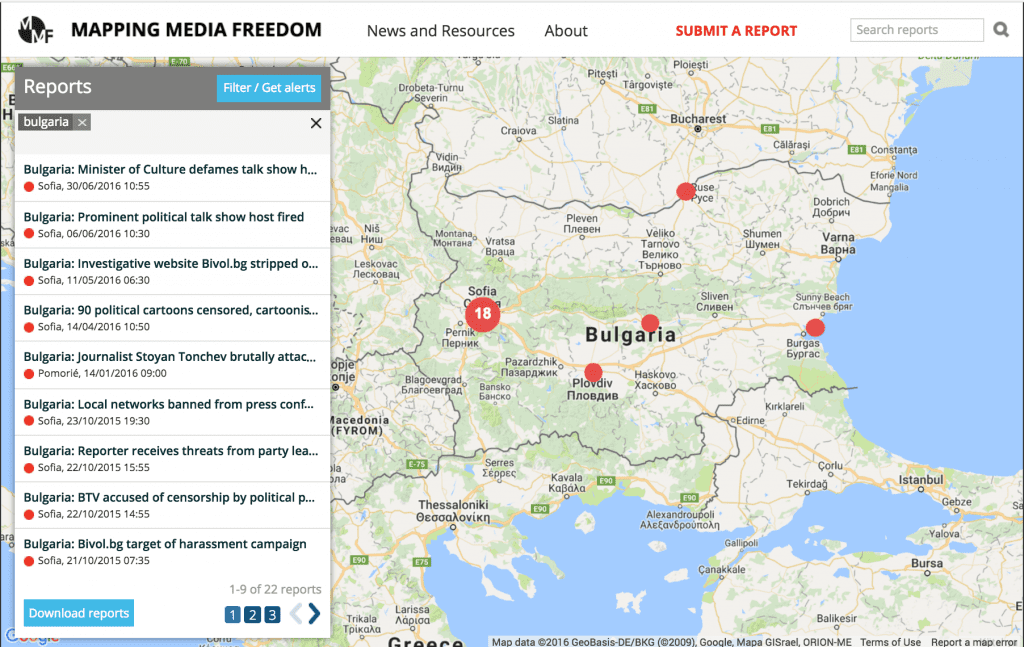

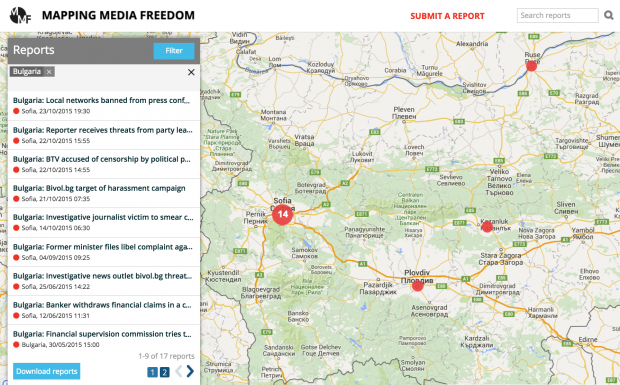

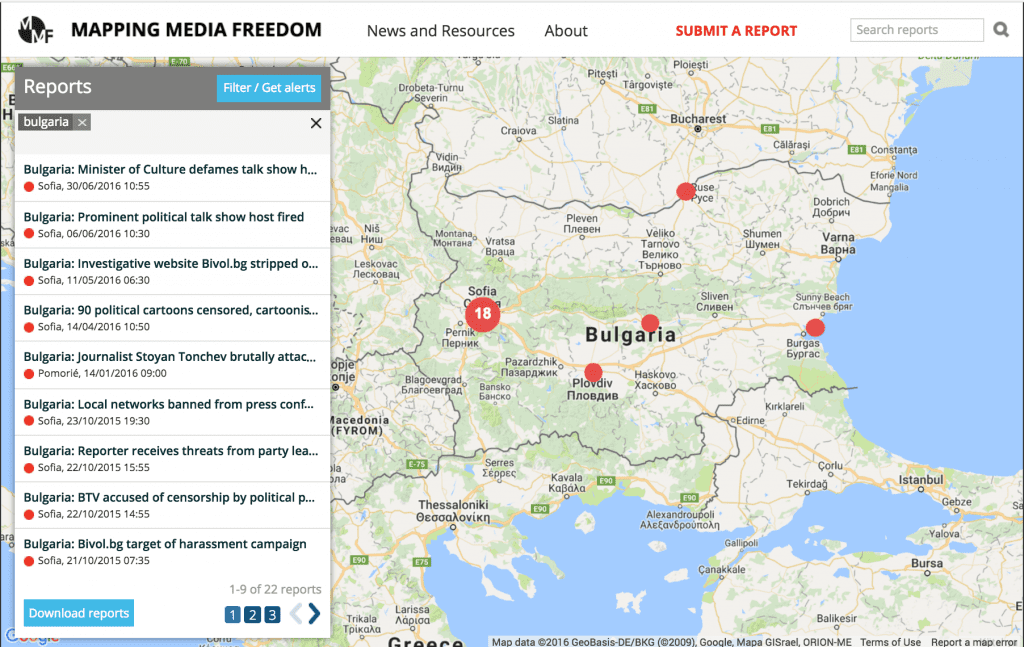

Sipos has made 40 reports of media freedom violations in Bulgaria since the project’s launch in 2014.

In May 2018, a report was filed of an investigative journalist was assaulted outside his home in Cherven Bryag, a town in northwestern Bulgaria.

Hristo Geshov writes for the regional investigative reporting website Za Istinata, works with journalistic online platform About the Truth and hosts a programme called On Target on YouTube. In a Facebook post, he said the attack was a response to his investigative reporting and “to the warnings [he] sent to the authorities about the management of finances by the Cherven Bryag municipal government”.

Geshov faced harassment after publishing a series of articles about government irregularities, in which he claimed that three municipal councillors were using EU funds to renovate their homes.

“It is unacceptable that Bulgarian journalists should be the target of physical attacks and that there should even be plots to kill them, simply because they are engaged in investigating official corruption,” Paula Kennedy, the assistant editor for Mapping Media Freedom, said.

“The authorities need to take such attacks seriously and do more to ensure adequate protection for those targeted.”

Bulgarian journalists are also being limited by legislation designed by politicians as a means of censorship. Backed by Bulgarian MPs, amendments to the Law for the Compulsory Depositing of Print Media would force media outlets in the country to declare any funding, such as grants, donations and other sources of income that they receive from foreign funders. Ninety-two members of parliament voted for the amendments on the first reading on 4 July, with 12 against and 28 abstentions. Unlike most legislation, there was no parliamentary debate beforehand.

With the second reading due in September, when it will have to be once again approved by parliament, and the president still has the right to veto it, amendments would force outlets to clearly state the current owner on their website, how much funding they received, who it was from and what it is for.

MPs claim the aim is to make the funding of media organisations more transparent.

Referred to as “Delyan Peevski’s media law”, the amendments were first proposed in February 2018 by MP Deylan Peevski, a politician and media owner. Almost 80% of Bulgarian print media and its distribution is controlled by Peevski, former head of Bulgaria’s main intelligence agency and owner of the New Bulgarian Media Group.

The amendments will create two categories of media, separating those funded by grants and those who receive funding from “normal” practices such as bank loans, which they are not obliged to declare. Peevski-owned media is funded predominantly through bank loans, with his family receiving loans from now-bankrupt Corporate Commercial Bank.

There are few independent media outlets remaining in Bulgaria, with fears the new law will only increase the level of self-censorship within the country. Amendments will put additional pressure on media outlets that rely on foreign grants and donations to maintain their editorial independence.

Atanas Tchobanov, co-founder of Bivol, told MMF the amendments are a way to “whiten [Peevski’s] image”, adding: “The bill is exposing mainly the small media outlets, living on grants and donations. If a businessman gives [Bivol] €240 per year with a €20 month recurrent donation and we disclose his name, his business might be attacked by the Peevski’s controlled tax office and prosecution.

“Delyan Peevski has blatantly lied about his media ownership in the past. Then, miraculously, he started declaring millions in income, but this was never found strange by any anti-corruption institution.”

The level of transparency required of independent media owners has become a major issue within the country, threatening independent journalism and editorial independence.

Speaking at the biannual Time to Talk debate meeting in Amsterdam, Irina Nedeva from The Red House, the centre for culture and debate in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, Bulgaria, tells Index: “We live in very strange media circumstances. On the surface, it might look like Bulgaria has many different private media print outlets, radio stations, many different private tv channels, but in fact what we see is that especially in the print press, more of the serious newspapers cease to exist.”

“They don’t exist anymore, they can’t afford to exist because the business model has changed and what we see is that we have many tabloids,” she adds. “These tabloids are one and the same just with reshaped sentences.”

Nedeva is concerned that such publications don’t adequately criticise the government or businesses. “They criticise only the civil society organisations that dare to show the wrongdoings of the government for example.”

In an effort to examine media ownership within Bulgaria, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom undertook a press freedom mission in June 2018. The mission found money from government and advertising is distributed to media considered to be compliant. EU funding is controlled by the government, giving those in charge the power to decide which publications receive what. This has created an atmosphere of self-censorship, dubbed “highly corrupting” by an ECPMF into press freedom in Bulgaria.

“There seems to be no enabling environment, politically or economically for independent journalism and media pluralism”, describing the media situation as a “systemic symptom of a captured state,” Nora Wehofsits, advocacy officer for ECPMF tells Index. “If the new media law is accepted, it could have a chilling effect on media and journalists working for “the wrong side”, as the media law could be used arbitrarily in order to accuse and silence them.”

Lada Price, a journalism lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University and Director of Education at the Centre for Freedom of the Media describes for Index the role the media owners play: “There’s lots of abuse of power for personal gain and I think, therein lies the biggest issue for free speech in Bulgaria. Media outlets are not being bought for commercial purposes, but for political purposes. They like to follow their own political and business agendas, and they’re not afraid to use that power to censor criticisms of government or any corporate partners.”

Price says that while the constitution guarantees the right to receive and disseminate information, the media landscape in Bulgaria is very hostile for journalism “because of the informal system of networks, which is dominated by mutual, beneficial relationships”.

“There is a very close-knit political, corporate and media elite and that imposes really serious limits on what journalists can and can not report,” she says. “If you speak to journalists, they might say whoever pays the bill has a say on what gets published and that puts limits on independence. There is no direct censorship, but lots of different ways to make journalists self-censor.”

ECPMF also said in its report into press freedom in Bulgaria that the difficulties media workers face are due to the current censorship climate, adding: “It is difficult to produce quality journalism due to widespread self-censorship and the struggle to stay independent in a highly dependent market.”

Funding from the EU and its allocation has become a controversial issue for media outlets in the country. In January 2018 ECPMF called for fair distribution of EU funds to media in Bulgaria, saying “the Bulgarian government should disseminate funds on an equal basis to all of the media, also to the ones who are critical of the government”. It also requested that the EU actively monitor how EU taxpayers’ money is spent in Bulgaria.

Bulgarian journalism is heavily reliant on EU funding and during the economic crisis of 2008/2009, advertisement revenues fell, making both print media and broadcasters much more dependent on state subsidies.

“When it comes to public broadcasters, they are basically fully dependent on the state budget,” says Price. “That means funding comes from whoever is in power, so they are very careful of what kind of criticisms [they publish], who they criticise. Their directors also get appointed by the majority in parliament.”

“The funding schemes that put restrictions on journalism is by EU funding, which shouldn’t really happen,” she adds. “But if you have your funding which is aimed at information campaigns then that is sometimes channelled by government agencies, but only towards selected media, which we see in the form of state advertising, in exchange for providing pro-government politic coverage.”

According to the US State Department’s annual report on human rights practices, released in April 2018, media law in Bulgaria is being used to silence and put pressure on journalists. ECPMF, in a report released in May 2018, described the current legislation as not adequately safeguarding independent editorial policies or prevent politicians from owning media outlets or direct/indirect monitoring mechanisms.

This was also reiterated by the US State Department’s report, which highlighted concerns that journalists who reported on corruption face defamation suits “by politicians, government officials, and other persons in public positions”.

“According to the Association of European Journalists, journalists generally lost such cases because they could rarely produce hard evidence in court,” the US State Department said.

The report also showed journalists in the country continue to “report self-censorship, [and] editorial prohibitions on covering specific persons and topics, and the imposition of political points of view by corporate leaders,” while highlighting persistent concerns about damage to media pluralism due to factors such as political pressure and a lack of transparency in media ownership.

Nelly Ognyanova, a prominent Bulgarian media law expert, tells Index that the biggest problem Bulgaria faces is “the lack of rule of law”.

“In the years since democratic transition, there is freedom of expression in Bulgaria; people freely criticise and express their opinions,” she says. “At the same time, the freedom of the media depends not only on the legal framework.”

In her view, the media lacks freedom because “their funding is often in dependence on power and businesses”, and “the state continues to play a key role in providing a public resource to the media”.

“The law envisages the independence of the media regulator, the independence of the public media, media pluralism. This is not happening in practice. There can be no free media, neither democratic media legislation, in a captured state.”[/vc_column_text][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGNzUlMkZtYXAlMjIlMjBmcmFtZWJvcmRlciUzRCUyMjAlMjIlMjBhbGxvd2Z1bGxzY3JlZW4lM0UlM0MlMkZpZnJhbWUlM0U=[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1536667459548-83ac2a47-7e8a-7″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Sep 2016 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

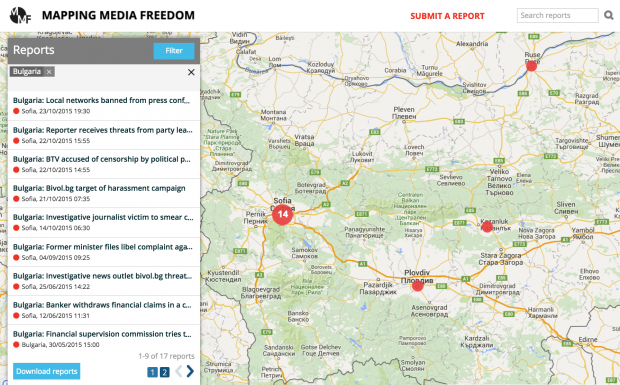

Between 2013 and 2015, 10 Bulgarian municipalities spent a total of 2.7 million Bulgarian lev ($1.54 million) – mainly to media companies and PR agencies – in return for positive coverage of their activities, an investigative series by news site Dnevnik.bg found.

According to the articles, the local governments of the five largest, excluding the capital Sofia, and five of the poorest cities in the country were found to be engaging in “corrupt practices” and displayed a disregard for “journalistic ethics and loyalty to the audience”.

Under the guise of using contracts to create advertisements, “job posting messages and other texts” – not only in publications but also for radio and television broadcasts – all 10 municipalities were found to be buying influence in media outlets and attempting to eliminate criticism, Spas Spasov, the author of the series, told Index on Censorship. The cities reviewed were Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Pleven, Stara Zagora, Shumen, Kazanlak, Blagoevgrad, Vratsa and Montana.

The data, which was obtained through freedom of information requests, does not claim to be exhaustive but provides an indication of administrative control over news in the cities covered by the investigative reports. “The idea behind the project was to reveal the deep crisis in which freedom of the press finds itself in Bulgaria,” Spasov said.

One visible trend in the series is that media content is sold at a discount to local governments who buy “wholesale”.

“The results of my investigation show that virtually all the media in the analysed municipalities are dependent on the public funding they get,” Spasov told Index. The lack of an advertising market outside the capital only strengthens this dependence on handouts from local government, he added.

|

This article is a case study drawn from the issues documented by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project that monitors threats to press freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries.

|

|

He found that in many cases the money private media outlets receive from municipal administrations often covers the entirety – or at least a significant portion – of their budgets. In one case a source told Spasov that the entire salary of a journalist was covered by Vratsa municipal funding.

In the city of Varna some advertising contracts were signed by municipal companies that are monopolies that were not in need of advertising. Spasov said that this is a way to buy political and institutional influence in a media outlet.

Many municipalities were found to be contracting “advertising” and “promotional activities” through private media despite the fact that almost every municipality has its own municipal media, through which they already publish official announcements.

“Of course, there is nothing vicious in the practice of municipal administrations buying advertising in private media,” Spasov said. He does, however, stress that in order to avoid buying media influence, local administrations and government institutions should publish their advertisements only in media outlets that comply with the Ethical Code of the Bulgarian Media.

“This code clearly stipulates that all text covered by the contracts will be marked as sponsored content but this is not the current practice,” he said, adding that vague wording–phrases such as “other texts”–helps to disguise sponsored articles published as editorial content.

This is possible because Bulgaria has no law requiring print and online media outlets to label sponsored content they are publishing. Existing regulation only addresses television advertisements.

“Transparency of sponsored content is crucial for a functioning free press. It is vital that existing legislation on advertisers be reformed swiftly to include all media outlets in order to protect the public,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

The investigation went on to find that many media outlets from smaller municipalities were created by political entities with the purpose of bullying their opponents in local government.

Spasov told Index that if the remainder of the country’s 256 municipalities were also to be investigated, “there should be no doubt” that the findings would be similar to the 10 which were analysed in his investigation.

11 Jan 2016 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Journalists of the Bulgarian investigative news website Bivol.bg are facing an orchestrated smear campaign that’s unusual even for Bulgaria, the worst-ranking EU member in the 2015 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.

The attacks can be linked to mainstream media outlets controlled by the Bulgarian media mogul and lawmaker Delyan Peevski, and seem to be a response to a number of investigations published recently by Bivol.bg, all involving Peevski in one way or another.

“Even if it is not like in the beginning, the smear campaign did not end,” Bivol’s editor-in-chief, Atanas Chobanov, told Index on Censorship in December 2015.

During the autumn, articles denigrating Chobanov and Assen Yordanov — Bivol’s founder, co-owner and director — began appearing in media outlets such as the Bulgarian weekly Politika, the Telegraph, Monitor and Trud dailies, as well as the news website Blitz, which are controlled either directly or through proxies by Delyan Peevski, an MP from the parliamentary group of the Turkish minority party, Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF).

According to a summary published by OCCRP, the articles allege that Yordanov uses Bivol.bg to publish fake stories to blackmail politicians and business people. The attack pieces allege that Bivol.bg publishes stories about environmental issues to serving the interests of fake eco-activists who pose as people concerned about the environment to extract cash from firms that want to build in the Bulgarian mountains and on the Black Sea coast.

There are allegations saying that Atanas Chobanov is a former Komsomol activist (the youth division of the Bulgarian Communist Party), aspired to a political career, and has links to a businessman whose media strongly oppose Peevski. Some articles insinuate that Chobanov works for foreign intelligence services; and that he lives a luxurious life in Paris where he milks the social welfare system. (The latter allegation is interesting because in 2013, it was Chobanov who uncovered that former planning and investment minister Ivan Danov was collecting €1,800 per month in unemployment benefits in France while working two jobs in Bulgaria.)

The pieces give a thoroughly negative depiction of Chobanov, saying that he is greedy, aggressive, mentally unstable, narcissistic, disliked and unwanted.

The campaign culminated on 10 October, when a crew of the Bulgarian TV Channel 3, a television where Peevski is a co-owner, showed up at the rented apartment in Paris where Chobanov and his family lives.

“I was at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Lillehammer, Norway,” Chobanov said, adding that the crew did not try to contact him by phone, e-mail or by any other means in advance. The journalist believes they must have known that he was away because he made a public announcement about his upcoming trip and he was tweeting from Lillehammer.

Although Bivol.bg was the target of similar articles in the past, the ongoing campaign started when the investigative news site published proof that Peevski is a shareholder at the Bulgarian cigarette maker Bulgartabac, a former state-owned company that underwent a controversial privatization process in 2011.

Then the journalists started publishing a story about the disappearance of €26 million ($28.3 million) from an EU food aid program for the poor, where the majority shareholders of Bulgaria’s First Investment Bank (FIB) were implicated. “After the Bulgarian bank crash, Peevski moved his assets, his credits and deposits to this bank, so this investigation also hurts Peevski’s interests,” Chobanov said.

Next, Bivol.bg broke “Yaneva Gate”, a series of stories based on leaked phone conversations between former Sofia City Court president Vladimira Yaneva and fellow judge Roumyana Chenalova over unlawful surveillance warrants that Yaneva had signed.

In those conversations, the judges mentioned Peevski by his first name, Delyan. “The Prosecutor General, one of the men of Peevski, is also involved,” Chobanov pointed out, adding that the story provoked an earthquake in Bulgarian politics, causing justice minister Hristo Ivanov to resign.

“It is a judicial battle now. We are turning to courts to stop the smear campaign, and we are also defending ourselves from legal complaints filed for the investigations we did in the past,” Chobanov said.

Reporters Without Borders expressed support and sympathy for Chobanov, condemning the smear campaign directed against him. “We can only condemn what are clearly attempts to intimidate Bivol’s journalists,” said Alexandra Geneste, the head of the Reporters Without Borders EU/Balkans desk. “Their investigative work is perfectly legitimate and we express our most sincere support and sympathy for them.”

The smear campaign orchestrated by the media outlets controlled by Peevski took an unexpected turn when they accused Xavier Lapeyre de Cabanes, the French Ambassador to Bulgaria with unacceptable meddling in Bulgaria’s affairs after he shared on Twitter a link to the press release by Reporters Without Borders with the comment: “Press freedom has no borders.”

The Bulgarian Association Network for Free Speech also issued a position saying that “the integrity of Bivol’s investigations and publications has not been and is not challenged in any way, despite repeated attempts to pressure our colleagues. (…) We have no reason to doubt the good faith of our colleagues, the journalist from Bivol (…).”

22 Dec 2014 | Bulgaria, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Politics and Society

Murky ownership, a whole array of censorship practices as well as corruption are plaguing Bulgarian media, according to a survey from the Bulgarian Reporter Foundation.

The report, Influence on the Media: Owners, Politicians and Advertisers, is based on surveys with 40 media outlets carried out between January and September 2014. One hundred journalists and 20 media owners were questioned about their perception of censorship in the Bulgarian media.

The report found that journalists, senior editorial staff and owners are offered bribes by politicians and corporations. While these allegations are very difficult to prove, there is a widespread assumption among people working in the media that reporters in certain sectors receive regular payments from large companies to present them in favorable light.

“It is very hard to prove the (existence of) bribes”, said Dr. Orlin Spassov, one of the authors of the report, who is an associate professor in media and communication studies at Sofia University and executive director of Media Democracy Foundation.

There are no court cases related to the bribes, Spassov told Index. “We collect the information using anonymous interviews. In other circumstances, journalists would hardly share such statements. Even under conditions of anonymity guaranteed, some of them were afraid to speak.”

Bribes can come in many different forms, the report found. From low-interest rates offered by certain banks to luxury trips, expensive presents or even as little as the payment of a phone bill.

Corruption among editors-in-chief is also considered a widespread phenomenon. The report mentions an editor-in-chief who received a record-high amount of 5 million Leva (EUR 2,5 million GBP 2 million) for changing the orientation of a media outlet to support a political party.

Media owners are also seen as corrupt. A leaked document, which was posted online, showed that a football club transferred five-digit amounts to a sports daily for its “favorable attitude”. According to journalists, media outlets sometimes blackmail companies or local authorities by threatening negative coverage unless the target buys advertising in the publication.

According to the report, the lack of media ownership transparency is one of the biggest problems. There are a number of media outlets owned by off-shore companies, anonymous joint stock companies or bogus owners. Even if the owners are known, it is sometimes difficult to see their interests and their finances. Public registers show that in Bulgaria the majority of media outlets are making losses. The fact that a number of prestigious foreign media companies have withdrawn from the Bulgarian market in recent years made things even fuzzier.

Documents that emerged after the Corporate Commercial Bank crisis showed that politics, mass media and finances are entangled in an unhealthy knot. This marks the relationship between journalists and media owners, the report points out.

There is no clear border between the owners and the senior editors. Thirty-five per cent of the surveyed senior editors say that the owner interferes with their work. Moreover, 20 per cent stated that they are sanctioned if they refuse to follow the owner’s instructions. Thirty-six per cent of the journalists consider that there are things they cannot tell the public through their media and 16 per cent confess that they are not convinced on everything their publication publishes.

A number of media owners see their media outlets as a tool for helping or protecting their other business interests. In May 2014, an internal document was published containing instructions given by one of the owners of an influential media group to the journalists of his papers and website on how to cover an issue about the withdrawal of licenses of electricity distribution companies.

The broader the audience a media outlet has, the stronger the pressure it faces from politicians. In Bulgaria, it is a common practice that MPs or members of the government call or send SMS messages to owners, senior editors or even journalists if they are not happy with their coverage.

If a media outlet does not comply with their demands, politicians often deprive “unfriendly” media of information. Their reporters would not be invited to certain events or do not receive information which their competitors are given access to. If politicians are reluctant about a certain topic, they would refuse to participate in the talk programs. Because journalists are obliged to present all points of view, they need to drop the topic from the agenda.

Sometimes authorities also misuse the Access to Public Information Act to obstruct the access to certain media outlets. When journalists request information from ministries and other departments, they are asked to file a freedom of information request that are replied only after 14 days, the period mandated by law.

The main leverage of central and local authorities over the media is the publication of paid announcements. This is an important source of revenue for Bulgarian media, especially because advertising has strongly declined due to the economic crisis. The report cites an editor-in-chief saying that the biggest advertiser is the state. Openly there are no conditions posed to obtain advertisements, but there is an assumption that critical media outlets will not receive contracts.

Commercial advertisers also have a strong influence on the editorial output of Bulgarian media. Companies routinely ask for materials that present them in a positive light as a condition of buying advertising. Sometimes they ask outlets to play down or ignore customer complaints or run critical coverage of their competitors. Many times there is no clear differentiation between the sponsored and editorial content, the report found.

Intra-editorial censorship is also widepsread in the Bulgarian media. Easily controllable, loyal journalists are promoted into responsible positions. They make sure political positions and orders are given a professional justification, this way reporters do not feel the political pressure from their peers. Sometimes negative comments are erased from the internet.

Personal blogs are seen as a way to circumvent editorial influence, with more or less result. In one case a journalist had to close his blog after he came under pressure from the senior editorial staff. In some media outlets, journalists are forbidden to have personal blogs, other owners allow them only by written authorization.

The survey and report were completed with the support of the Sofia office of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and its Media Program South East Europe.

For more on media violations in Bulgaria, visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was posted on 22 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org