26 Mar 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/7kseuuaARZQ”][vc_column_text]The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) is one of the only human rights organisations still operating in a country increasingly hostile to dissent and in which countless civil society organisations have been forced to close. The commission coordinates campaigns for those who have been tortured or disappeared, as well as highlighting numerous incidences of human rights abuses.

“Our main goal to achieve in the future, which is stated in our mission, is to empower individuals to acquire their rights, promote a culture of democracy in the Egyptian society, and expand human rights to every home in Egypt,” ECRF told Index. “But in the end of the day we decide to carry out with our work regardless of the challenges because if everyone is silenced this would be the ultimate gain to the current regime, and the ultimate victory to Egypt’s state of fear.”

Between August 2016 and August 2017, the ECRF documented 378 cases of enforced disappearance many of whom were students. The cases of the disappeared are not reported in the heavily censored local media, and the commission’s website and social media sites are some of the few places their plight can be publicised, reported and mapped.

The highly restrictive and repressive environment Egypt has made it increasingly difficult for the organisation to do its work.

Their website was blocked in September in government measures designed to close the organisation down, but the ECRF managed to create a parallel website to maintain their presence and engagement with the public. Twice last year ECRF’s headquarters was raided by security forces with two staff members being arrested. As a result, the staff need help dealing with the risks of being arrested, as well as dealing with the interrogation process and knowing how to protect information.

Over the past 12 months the ECRF has been fighting censorship and defending human rights in two ways. The first is through the criminal justice programme which tackles issues of torture and enforced disappearances in Egypt. It has been particularly focused on the arrest of activists who took part in demonstrations against Egypt’s agreement to cede two uninhabited islands in the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia.

Secondly, ECRF has worked on challenging censorship imposed on student associations in universities. Recently the commission launched an online platform to bring students and practitioners online to discuss a student charter related to freedom of association in universities. The platform was heavily criticised by the ministry of higher education in Cairo, which led to further condemnation of it in official media outlets.

As a direct result of the work ECRF has carried out over the past year, there has been an increased awareness of enforced disappearances, media censorship, the scale of torture, and violations of freedom of association and expression in media and universities.

“ECRF is honored to be shortlisted alongside three peer organizations/campaigns also facing severe human rights challenges in their own countries,” said ECRF. “The international recognition of ECRF’s efforts in campaigning for fundamental freedoms emboldens its members and staff in their resilience to strive for human rights and democracy in Egypt. Regardless of the winner, progress towards equal rights in Russia means progress in Egypt and progress in Kenya means progress in Iran and vice-versa.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522065946315-a2955265-bb40-3″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

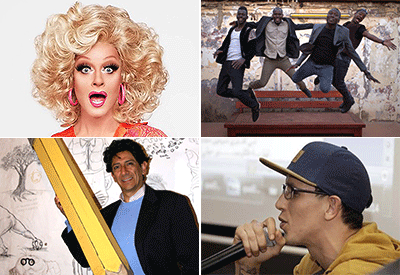

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jul 2012 | Europe and Central Asia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“I will be arrested the minute I land in Uzbekistan and then thrown in prison,” an Uzbek human rights activist tells me, “and what happens with me afterwards is a good question.”

For his family’s safety, I cannot tell you the name of the young man. Let’s call him Rustam, a common name in Uzbekistan.

“I only have five minutes, then they cut off the phone,” the 26-year old explains.

Since 12 June he has been held at the immigration services detention centre in Oslo, Norway, after having received the third and final rejection of his appeal for political asylum. He will be deported on 12 July.

Looking at his case it is obvious that the Norwegian authorities are ignoring evidence showing that returning Rustam to Uzbekistan is as good as sentencing him to torture, even death. They have also disregarded UN evidence that says returned Uzbek dissidents who sought refugee status abroad have been disappeared and subjected to torture.

It is easy to detect the fear in Rustam’s voice. In 2004, he and some friends started an NGO called Movement for Freedom and initiated a campaign against child slave labour. Every year, two million Uzbek school children — the youngest just 7 years old — are forced to spend six to eight weeks picking cotton, eight to 10 hours a day.

Uzbekistan has been heavily criticised for this abuse of children. But the income from cotton exports runs into hundreds of millions of dollars, and much of it falls into the pockets of the Uzbek dictator Islam Karimov, who has been in power for 23 years since Soviet times.

When Rustam and his friends started their campaign against child slavery, he was detained and tortured. Upon his release, Rustam fled to Russia. While he was in hiding, he heard that one of the Movement’s co-founders had been killed in an Uzbek prison. He decided to move on to Norway.

I understood how dangerous it would be for me if I returned or was extradited…I too could very easily be killed.

Russia, a close ally of the Karimov regime, routinely extradites Uzbeks. Afterwards many of them ‘disappear’.

The authorities in Norway have two problems with Rustam’s plea for asylum:

1/ Rustam does not have a passport. Rustam says he threw it away when he smuggled himself out of Uzbekistan to ensure he could not be identified by the police if he was apprehended. But it means outside Uzbekistan Rustam now cannot prove that he is who he claims to be.

2/ While Rustam was in Norway hoping to be granted asylum, he started working as a volunteer for the Uzbek human rights defender Mutabar Tadjibaeva. This is now the heart of Rustam’s appeal: the Norwegian authorities do not believe that he worked as her webmaster.

Because of her international standing, Tadjibaeva is hated by the Karimov regime; working with her would land Rustam in very serious trouble in Uzbekistan.

Tadjibaeva has been living in exile in France since in 2008 escaping after three years of prison, rape and torture in Uzbekistan. The country has more than 10,000 political and religious prisoners and experts put it amongst the harshest dictatorships in the world, on par with North Korea.

Tadjibaeva runs the website Jayaron, one of very few independent sources of information about Uzbekistan, a country in which media are strictly controlled by the regime. She has established a widespread network of informants inside the country who send her details about corrupt court cases, unfair imprisonments and cases of torture. Her site is a thorn in the side of a regime that has almost managed to completely isolate its population from the outside world.

The Karimov regime call Tadjibaeva an “extremist” and accuse her of planning to overthrow the government, which is rather difficult to imagine when you meet her in person — a small, soft-spoken 49-year-old woman, her health scarred by years of torture and prison.

In 2008 the US State Department gave Tadjibaeva the prestigious Woman of Courage award. After Tadjibaeva received it, a Wikileaks telegram revealed that the American ambassador in Tashkent received a “tongue lashing” from the Uzbek dictator, who threatened to block US transit to Afghanistan in retaliation.

The ambassador advised his government to tone down the criticism of the Uzbek regime, advice they took. And relations are nearer to the close relationship the countries enjoyed before Karimov’s army killed 800 demonstrators, many of them women and children, in May 2005.

Mutabar Tadjibaeva stresses to me that Rustam has worked with her since August 2010. She cannot understand why the Norwegian immigration authorities rejected Rustam’s asylum plea, stressing that they do not believe that he and Mutabar work together.

We have worked closely together, you can even find his name on our website. Because of this, his life would be in great danger if he were returned to Uzbekistan.

“The Uzbek regime does not like people telling the truth,” she adds. “I have no less than 343 emails here in which we discuss Rustam’s work with our website and my blog,” she tells me, “that obviously prove that we worked closely together.”

“If the Norwegians really wanted to know the truth, all they have to do is check his computer, mobile phone and emails.” She showed me the email and text communication between the two.

“I have even transferred money to him in Norway, so he could buy a computer and work on our website,” Mutabar explains. She shows me receipts.

If he is sent back to Uzbekistan, a long time in prison and severe torture awaits him. There is a real risk that the regime will kill him, as a warning to others to stay away from human rights work.

At the moment it looks like that Rustam will be deported to Uzbekistan within the next week.

But in June something happened which Mutabar hopes will help Rustam. The UN Committee against Torture censured Kazakhstan — Uzbekistan’s neighbour — for deporting 29 Uzbek asylum seekers in 2010. Several of the 29 were later given lengthy prison sentences, kept in isolation and therefore, say analysts, most likely tortured.

UN conventions forbid states deporting people to their home countries if there is a risk that they will be tortured.

Exact numbers are impossible to come by — this is Uzbekistan — but according to local human rights organisations dozens of people are tortured to death each year in Uzbek prisons, and the favourite victims of the security police are those who have been in the West asking for asylum or even speaking poorly about the regime. This description clearly applies to Rustam.

Mutabar Tadjibaeva hopes that the UN decision will make Norway re-consider his case. “But,” she adds, “so-called democratic countries in Europe have often shown themselves full-willing to close their eyes to the atrocities of the Uzbek regime. I have lost all faith in them.”

Michael Andersen is a Danish journalist who has covered Central Asia for more than 10 years. His newest feature-length documentary on Uzbekistan is called Massacre in Uzbekistan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]