20 Oct 2016 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

Index on Censorship believes that everyone has the right to express their opinion, no matter how vile or offensive those views, unless their words directly incite violence. For this reason, we believe that the Independent Press Standards Organisation was right to reject a complaint by Channel 4 News about comments made by Sun newspaper columnist Kelvin MacKenzie regarding Channel 4 journalist Fatima Manji.

MacKenzie’s views are offensive. But they were his opinion and he should be entitled to express his opinion – just as are – thankfully – the vast majority of people who have come out publicly to criticise and dismantle his views in open debate.

8 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Ireland, News and features

This week the Plain People of Ireland (both the physical and metaphorical place — more on that later) wailed, gnashed teeth, shook their fists at passing clouds and, of course, took to Twitter to express their horror, over a situation comedy.

Well, not an actual situation comedy. More an idea, that may turn into a script, that may, at some point, but probably not, turn into a comedy series. Still though…

It started harmlessly enough, in an end of year feature in the Irish Times (a newspaper not noted for sensationalism). Bright young things told of their plans for 2015. One, scriptwriter Hugh Travers, told the paper about his planned script for a sitcom called Hunger, which was in development stage with the UK’s Channel 4. The comedy would be based during the Irish famine. “I don’t want to do anything that denies the suffering that people went through,” said Travers, “but Ireland has always been good at black humour.”

Oh Hugh, how right you are. If there’s one thing everyone knows about us Irish, it’s our great sense of humour. We are, no doubt, a great bunch of lads when it comes to laughing.

But we are also, and let us be clear on this, a people with a profound sense of our own history; a nation carrying with us the struggle of generations and the ghosts of our patriot dead.

Or, to put it another way, we’ve got baggage. Playwright Brendan Behan said that: “Other people have a nationality. The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.”

A large part of that baggage, that psychosis, comes from the great famine of the mid 19th century.

The famine of 1842-1847 was probably the bleakest period in Irish history. At least in population terms, the country has never really recovered. Over a million died and millions more emigrated.

Not that Ireland had been bread and roses before that. Over a century before, Jonathan Swift had addressed poverty and hunger in rural Ireland with his satirical pamphlet “A Modest Proposal” (“A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public”, to give it its full title), which suggested a scenario where poor Irish people with large families should sell their children as food.

Even so, the 19th century famine was the worst of the worst, exacerbated by a government in London that was, at very, very least, negligent, and most certainly culpable. I will not get into a debate about whether it should be classified as a genocide or not, except to say that opinions either way on that judgment are too often based on what “side” one is on rather than evidence.

In any case, to get into that argument is to play into the hands of the brouhaha that followed Hugh Travers’ optimistic announcement of his plans in the Irish Times.

The fuss was kicked up by Niall O’Dowd, editor of Irish-American website Irish Central and, to judge by his extensive Wikipedia page, a very important man indeed.

New York-based O’Dowd wrote an article on his very important website, furiously denouncing the Channel 4 sitcom he couldn’t possibly have seen because it doesn’t exist.

It’s worth quoting the main thrust of his piece:

“What’s up next?? A sitcom on The Holocaust maybe with funny fat Nazis eating victims alive?

Or how about a comedy about Ebola with black kids dying on screen and doctors telling funny jokes about them?

‘Sure you are being way too sensitive,’ I can hear people say, ‘time to have a laugh about the Famine. Did you hear the one about the starving children? Some of them ate grass…Ha Ha Ha.”

Much like a homophobe denouncing gay sex, O’Dowd displays a remarkably vivid and well, dark imagination about what a comedy set during the famine might be: surely, he suggests, the thing that we are being asked to laugh at is the very worst thing you can dream of (Don’t get too smug about this point by the way; the converse of this could be that your relative lack of an outrage impulse stems from your relative lack of imagination. I know that’s true of me).

O’Dowd wonderfully went one further, writing another article for Irish Central in which he imagined the script for the proposed sitcom. Suffice to say, it was not funny, but not not funny in the way the author intended.

O’Dowd’s real problem, it seemed, was that Channel 4 was a British company making hay out of an Irish tragedy: he barely examined the fact that the originator of the script is an award-winning Irish author given an open brief. That would bring unwelcome complexity to the issue.

Last Monday, I was invited to discuss the issue on BBC Ulster’s Nolan show. I joked beforehand that the slot would degenerate into listing topics that we were and were not allowed to make comedy of. That was exactly what transpired, as my interlocutor, Irish commentator Jude Collins, began listing incidents and asking “Would you think that was funny?” — everything from 9/11 to the death of Ian Paisley (why the peaceful death of an old man was a tragedy on a par with the starvation of a million people was not made clear by Collins).

The problem with this line of thinking is that it’s not actually a line of thinking at all. It is mere positioning. Collins inadvertently demonstrated that once you start proscribing fit topics for comedy, you can’t stop. It’s always possible to find someone, somewhere who would be upset by practically any joke of substance. A caller into the show skewered Collins by pointing out he had stood against born-again Christians who had attempted to ban a comedy play based on the Bible (as reported by Index). Were they not offended? Did their feelings not count?

Those who raised their voice attempting to prevent the development of the famine script they couldn’t even have read — including the tens of thousands of Irish people at home and abroad who signed an online petition against the comedy — were simply parading their ignorance, much like the mullahs who condemned Salman Rushdie while boasting that they had not read the “blasphemous” Satanic Verses. They should think twice, or even once, before raising their hackles again.

This article was published on 9 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 2014 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

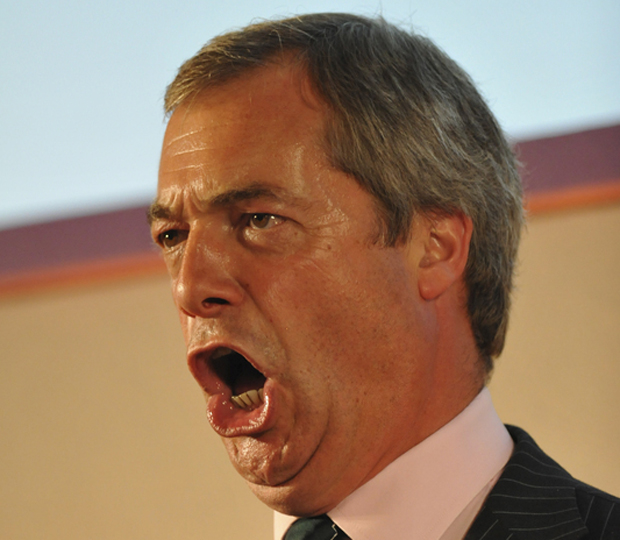

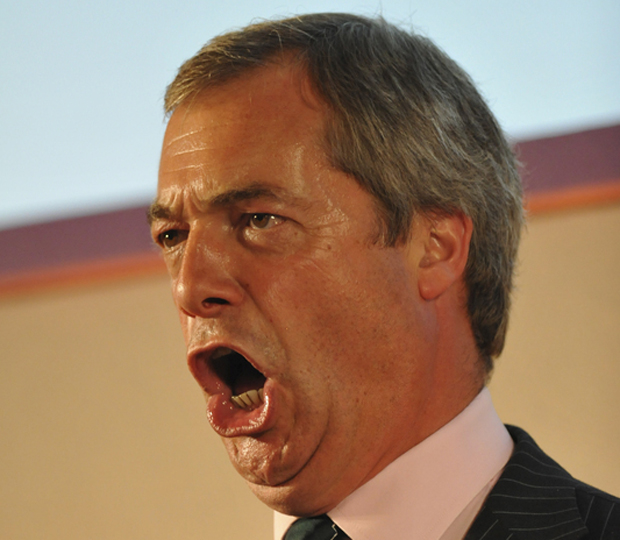

(Photo: Michael Preston / Demotix)

Ofcom’s decision to declare the UK Independence Party a ‘major party’ for the purposes of this month’s European elections has led to questions about who should be allowed to address the public. Behind the scenes, broadcasters have asked why their right to editorial freedom is restricted at all.

UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, responded: “This ruling does not cover the local elections, despite UKIP making a major breakthrough in the county elections last year. This strikes me as wrong.”

Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party – which Ofcom decided was not a major party – pointed out that, unlike UKIP, her party has an MP, and is also “part of the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament”.

Both sides pounced on the Liberal Democrats, whose dwindling position in the polls, they hinted, should see it demoted to minor party status.

The decision means commercial TV channels that show party election broadcasts must allow UKIP the same number of broadcasts as the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. They will also be given equal weight in relevant news and current affairs programming. However, for content focusing on, or broadcasting solely to, Scotland, UKIP’s lower levels of support there mean it will remain a minor player.

This of course gives UKIP a certain level of legitimacy, and the scope to influence even more voters. For those campaigning against them, the move is grossly unfair.

The Green Party in particular feels hard done by. From the House of Lords to local councils it has representatives at every level, but Ofcom still claims it hasn’t achieved enough. Yet in its report the regulator said that it could not make UKIP a major party in Scotland without granting the same status to the Scottish Green Party, due to their comparable performance.

Ofcom has promised to review the list periodically, so things could change in future. But for now it believes the list represents political realities. UKIP’s focus on getting Britain out of Europe has helped it to do well at the past few European elections. In 2009 it came second in terms of vote share, up from third place in 2004, and this year a number of polls indicate that it could win. In more recent local elections UKIP has done well, achieving 19.9 per cent of the total vote in 2013. But this has leapt up from 4.6 per cent in 2009’s local elections, which for Ofcom is not consistent enough to justify extra coverage for its prospective councillors.

So it seems fair enough that UKIP counts as an important party for Britain in the European Parliament. The Greens are yet to win enough votes in enough elections for their inclusion to make sense. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be clinging on only because of their level of support in past general elections, which was also taken into account.

But the real question is why a list is necessary at all. After all a “regulated free press” sounds something like “freedom in moderation” – ultimately a nonsense. Ofcom’s control over which parties receive coverage puts a dampener on broadcasters’ right to freedom of expression and makes it more difficult for newer parties to break through.

Responding to a previous consultation on whether the list of major parties should be reviewed, Channel 4 said the regulator’s rules should “ensure that political messages are conveyed in a democracy… [but] such regulation should be as narrow as possible to restrict… any interference with the broadcaster’s right to editorial independence and its rights to freedom of expression”. Channel 5, meanwhile, said the concept of major parties did not have “continuing relevance at a time of increasing political flux and fragmentation within the electorate”.

Ofcom appears to be prioritising the need of the electorate to be informed. So it could be argued that, for the purposes of allocating party election broadcasts, the list is useful to prevent any channel from steadfastly omitting information on a party that is likely to appear on most voters’ ballot papers.

But in terms of news and current affairs programming, there seems little reason that broadcasters shouldn’t have the freedom to say what they please – particularly because newspapers are faced with no such restrictions.

As the dominance of mass media fades, and the internet provides access to alternative points of view, the restrictions on the news you receive through your TV will only become more obvious.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org