15 Jun 2020 | News

Credit: Singlespeedfahrer/Petr Vodicka/Amy Fenton/Executive Office of the President/ Philip Halling/Isac Nóbrega/The White House

George Floyd. Dr Li Wenliang. Amy Fenton. JK Rowling. Edward Colston. Jair Bolsonaro. Donald Trump.

Love or loathe these people, the actions of each have opened a new debate in 2020. From the Black Lives Matter movement to the debate on sexuality, to the freedom of the press in the UK, to the role of Government and state actors hiding details of a public health emergency from their citizens.

If we have learnt anything at all from the turmoil that 2020 has given the world, it’s that free speech is vital; free expression is central to who we are and; that journalistic freedom is integral to the type of global society we aspire to live in.

Today, I’m joining the team at Index on Censorship as its new CEO. Index has spent the last half century providing a voice for the voiceless. Giving those who live under repressive regimes a platform to tell the world of their experiences and enabling artists to share their work with the world when they can’t share it with their neighbours.

Our work has never been more important. There have been over 200 attacks on media freedom across the globe, since the end of March this year, related to Covid-19. In the US alone there have been over 400 press freedom ‘incidents’ since the murder of George Floyd, including 58 arrests of journalists, 86 physical attacks and 52 tear gassings. In the UK, this weekend, on the streets of London we saw journalists attacked while reporting on a far-right demo in our capital.

My role in the months ahead is to highlight the threats to free speech, both in the UK and further afield, to celebrate free speech, to open a debate on what free speech should look like in the 21st century and most importantly to keep providing a platform for those people who can’t have one in their own country.

The editorial in the first edition of Index on Censorship in 1972, stated: There is a real danger… of a journal like INDEX turning into a bulletin of frustration. But then, on the other hand, there is the magnificent resilience and inexhaustible resourcefulness of the human spirit in adversity.

With you, the team at Index will continue to fight against the frustration while celebrating the magnificent resilience of the human spirit. And I can’t wait to get stuck in.

Ruth

PS Join us to protect and promote freedom of speech in the UK and across the world by making a donation.

12 Jun 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

Jordan, the UAE, Oman, Morocco, Yemen and Iran. It is the sort of list that Index might compile for any number of attacks on freedom of expression. In this instance they are all countries that have chosen to ban the printing of newspapers and other media during the current Covid-19 crisis, ostensibly to contain the spread of the virus.

This trend of governments using this pandemic to close down newsprint is one of a series of trends that we have identified in compiling Index’s mapping project . The map, created in conjunction with Justice for Journalists Foundation, tracks media violations during the coronavirus crisis.

On 17 March, the Jordanian Council of Ministers ordered newspapers to stop producing print editions for two weeks in a bid to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Minister of state for media affairs Amjad Adaileh said at a press conference that the decision was “because they help the transmission of the pandemic”. On 21 March, the UAE’s National Media Council announced a temporary ban on printing all newspapers and magazines except for regular subscribers of the publications and large outlets in shopping centres.

The council said the decision was “in line with the precautionary measures taken to contain the spread of the virus. Several people touching the same printed material has the potential to disseminate the virus.”

Over the next week, Morocco, the Sultanate of Oman, Yemen and Iran all followed suit, forcing publishers to produce copies online. In April, the Indian state of Maharashtra did things differently; it didn’t ban print publications but banned their delivery to people’s doors.

In early April, a number of Tunisian publishers suspended printing a number of daily and weekly publications.

Yet there is mounting evidence that there is little or no risk of catching the virus from newspapers, which has led Index to suspect that Covid-19 is being used as an excuse.

The World Health Organisation is reported to have said that the risk of contracting the virus from newsprint is “infinitely small”.

Professor George Lomonossoff, a virologist at the John Innes Centre said in a TV interview: “Newspapers are pretty sterile because of the way they are printed and the process they’ve been through. Traditionally, people have eaten fish and chips out of them for that very reason. So all of the ink and the print makes them actually quite sterile. The chances of that are infinitesimal.”

Former director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research N K Ganguly told the Deccan Herald: “It is more of a perception than reality that COVID-19 virus spreads through newspapers.

The risk of catching the virus from newsprint seems remote but some say the fear of it spreading that way is causing people not to buy print newspapers.

Vincent Peyrègne, CEO of the World Association of News Publishers, (WAN-IFRA) said:

“Today, modern newspaper production is fully automated from end to end. There is hardly human intervention until the last mile distribution point. The ink and solvent used in newspaper printing act as a disinfectant to a large extent and there is no evidence to show that newspapers are carriers of the virus. The rumours that the virus can spread through newspapers is also having a disastrous effect, and newspaper as a source of transmission of the virus is very remote.”

It is perhaps telling that the countries which appear high on various rankings of press freedom have not joined in with banning newsprint.

Peyrègne said these countries “banned print newspapers with the fallacious, or misleading argument that they needed to protect the health of citizens”.

“Any banning of media or placing of restrictions on journalists or media organisations is not only an attack on the freedom to inform and to be informed, but it also carries serious consequences in terms of responsibility for contributing to one of the most serious humanitarian and economic crises we have experienced in the last one hundred years. Nevertheless, many authoritarian countries feel that the crisis is the perfect excuse to crack down on free speech, silence their critics and accelerate repressive measures,” said Peyrègne.

The ban on print editions of newspapers and magazines has contributed to a devastating effect on circulations.

Peyrègne said: “The month of April hit the circulation of the daily press hard, due to confinement, the closure of sales outlets and the shutdown of transport. Generally speaking, readership and subscription surged dramatically during the lockdown. Some segments were obviously more affected than others.”

In the UK, the auditing body ABC has told publishers they no longer have to reveal their print circulations, a move which media trade journal Press Gazette says may mean we “never get the full picture of the impact of coronavirus on newspaper sales”. It says that News UK is the only major publisher to say it will not provide the figures so far.

The crisis has also seen a dramatic acceleration in the move of local newspapers away from print. Many local newspapers rely on advertising from their communities and most of these businesses have been forced to close during the crisis, sucking revenues from the publishers.

News Corp Australia announced at the end of May that 76 of its local and regional newspapers would become digital only while 36 others would cease publication permanently.

In the UK, JPIMedia said it was temporarily stopping the print publication of a dozen of its titles, including the MK Citizen in Milton Keynes and the News Guardian in North Tyneside.

In Egypt, Sawt Al-Azhar, Veto, Al-Youm Al-Gadid and Iskan Misr have all temporarily stopped producing print editions.

It is good to see that some countries, including Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan have reversed their bans but such incidents represent just a small part of wider crackdowns on media freedom that we are witnessing at this time of crisis and which we are reporting on our interactive map.

Newspapers play a vital role in informing communities, particularly at times of crisis, and the combination of misguided bans and the poor financial viability of some titles will be a loss that will be keenly felt.

Read more about Index’s mapping media freedom during Covid-19 project.

14 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

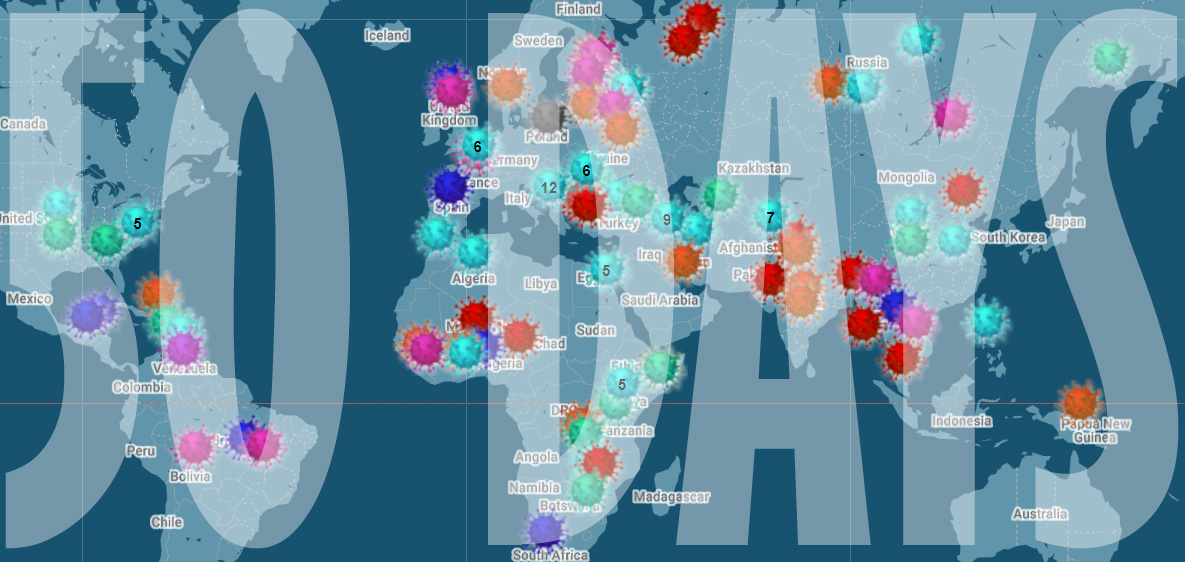

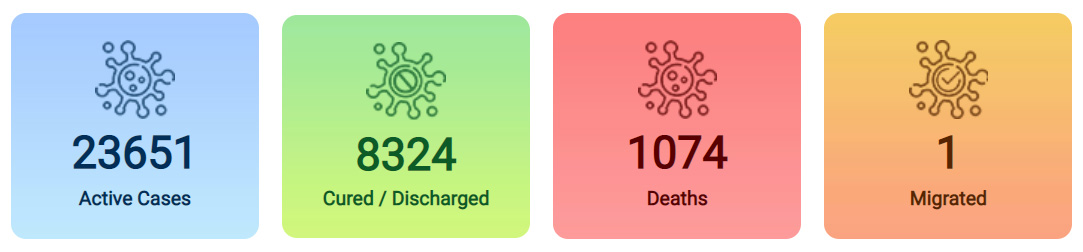

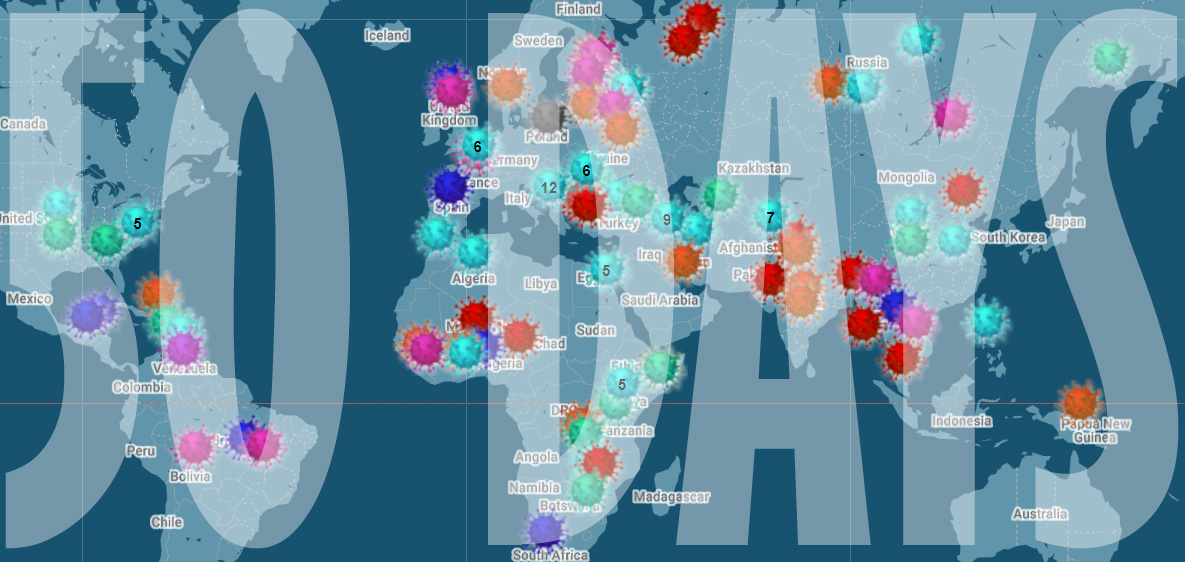

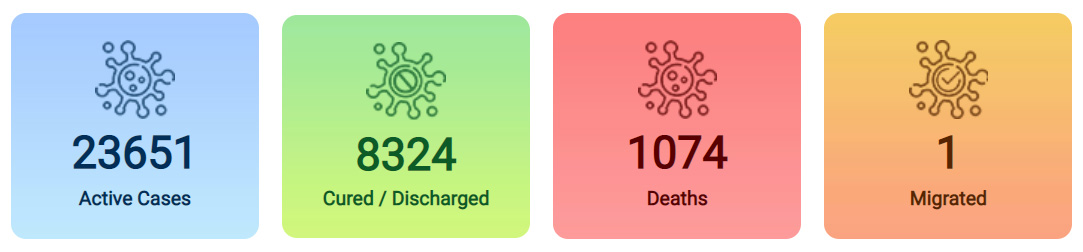

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 May 2020 | India, News

Image by Raam Gottimukkala from Pixabay

A friend in the police department apologetically texted me with some “friendly” advice. “Don’t be extra active on social media over corona issues which may lead to panic and rumours. There may be legal issues over it,” he said.

He wouldn’t elaborate further, but it didn’t take much to understand. A freelance journalist was arrested in Andaman and Nicobar Islands for a tweet on a bizarre quarantine rule. At least 13 people from various walks of life have been arrested since 1 April in Manipur for Facebook posts. A doctor at a government hospital had been harassed by the police and questioned for 16 hours at a police station after he put up a Facebook post complaining about the lack of protection gear for doctors. A founder of an online publication was arrested in Tamil Nadu for reports on problems faced by government healthcare workers. In Chhattisgarh, a journalist was slapped with a notice threatening arrest for his report on the plight of women in lockdown.

The pandemic has given the government free rein. India is witnessing very high levels of suppression of free speech and media censorship across the country.

“Everything is censored,” said a Kolkata-based journalist, declining to be identified. “You cannot report on anything that is not confirmed by the government. Getting data on anything is an ordeal.”

In the name of curtailing rumours and fake news, there have been curbs on free speech and freedom of journalists to cover the pandemic, especially those with questions that make the government uncomfortable. “It’s as if the media is an opponent. It is as if asking questions of the government is a crime, or a politically motivated exercise,” said the journalist.

On 30 March, Scroll.in published a list of ten questions that health beat reporters in Delhi had for the central government but did not get any answers. These included: How did the Indian government arrive at the pricing of the Covid test in private labs, which is Rs 4,500 ($60), and among the highest in the world? Why has the drug controller not released the list of Covid-19 testing kits that have been granted import and manufacturing licences? What are the steps the government is taking to map the scale of Covid-19 outbreak in the community? What arrangements have been made to ensure patients living with life-threatening conditions like cancer, tuberculosis and HIV that require continuous support are not deprived of critical care?

While questions such as these remain unanswered, journalists covering the Covid crisis say they are witnessing unprecedented levels of censorship. Government interaction with the press is stressed. Prime Minister Modi, in keeping with his record, has not organised a single press conference on the issue. Harsha Vardhan, a health minister, has interacted infrequently with the press, while the daily press briefings are conducted by a senior bureaucrat in the health department, Lav Agarwal.

“In the ministry’s organisation structure,” writes Vidya Krishnan in Caravan magazine, “Agarwal comes after two secretaries, four special secretaries and four additional secretaries, and is one of the thirteen joint secretaries in the ministry of health.”

Even the press briefings are not for all journalists. Barring Doordarshan (DD), India’s public broadcaster, and news agency Asian News International and a few accredited journalists, others have been barred from attending the press briefings in the name of social distancing. “The directive on social distancing became an excuse to not have journalists in the room,” said Anoo Bhuyan, Delhi-based health reporter with Indiaspend, a data journalism-based news portal.

“Then we got a message one day saying other than ANI and DD no one needs to attend the press conference. They said we could send our questions through WhatsApp. However, there is no guarantee that your question will be picked to be answered by Mr Agarwal. It is like a lucky draw without any rationale and definitely does not give equal chances to all journalists. In the very short time allotted for questions, only two to four questions are picked up, some of which are repetitions.”

The Modi-led government even approached India’s Supreme Court to legalise censorship by seeking an order that would prevent the media to publish anything “without ascertaining the true factual position” from the government. The court did not go that far, only directing the media to “refer to and publish the official version about developments”.

“The order itself does not have teeth, but the fact that there is an order may freak out many,” said Bhuyan. “It gets diabolical in that Lav Agarwal makes it a point to sometimes refer to the order and ‘remind’ journalists to ‘exercise caution’ and ‘report responsibly’.”

“What’s happening in India is extremely disturbing,” Vidya Krishnan, a Goa-based health reporter with Caravan magazine, tweeted on April 1. There is a media gag in place, doctors have been threatened to not speak out against lack of PPE kits, and the health ministry says we have no local transmission (without scaling up testing). Genuinely struggling to understand how we can continue reporting in this Orwellian setting.”

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, data correct as at 30/4/2020

Meanwhile, Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of the Indian state of West Bengal, announced insurance cover for journalists covering Covid from the frontlines. It is a combination of medical and life cover worth 10 hundred thousand Indian rupees (£10,500). There’s one rider: journalists have to do “positive” stories. “People are depressed seeing negative news all the time,” she said. “Journalists should be involved with the government,” she added without leaving anything to doubt.

This came just two days after she threatened legal action against journalists if they report “unconfirmed” fatality figures. Banerjee, who has a record of booking journalists, academics and the general public for social media posts critical of her, faces allegations that she is supressing Covid-related data in the state. The state has a special committee to “audit” and “ascertain” Covid deaths.

Banerjee has asked journalists to “behave properly” or face legal action.