24 Sep 2020 | News and features, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114982″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not set out to be an advocate for gender equality. Coming of age during the McCarthy Era of the 1950s, when freedom of speech and freedom of association were subject to intense scrutiny and repression in the United States, her initial goal was to uphold constitutional rights.

“There were brave lawyers who were standing up for those people [targeted by McCarthyism] and reminding our Senate, ‘Look at the Constitution, look at the very First Amendment. What does it say? It says we prize, above all else, the right to think, speak, to write, as we will, without Big Brother over our shoulders’,” she said in a 2011 interview. “My notion was, if lawyers can be helping us get back in touch without most basic values, that’s what I want to be.”

But as one of only nine female students in her 552-strong class at Harvard Law School, she quickly realised that she would face an uphill battle. This put her on track not only to become a feminist icon, but to become a voice for the few.

“Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so,” Index on Censorship magazine’s outgoing editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley wrote in her most recent editorial, not knowing then that RBG’s was to die the following week.

As a Supreme Court Judge, her dissenting opinions (which opposed the majority views that gave rise to judgements) became legendary. The fact that dissents do not carry the weight of the law did not dissuade Ginsburg from putting forward extensive opinions.

“Dissents speak to a future age,” she explained. “But the greatest dissents do become court opinions and gradually over time their views become the dominant view. So that’s the dissenter’s hope: that they are writing not for today, but for tomorrow.”

Ginsburg knew how to use her voice, but she also knew when to use it. “In every good marriage, it helps sometimes to be a little deaf,” she often told students, repeating the advice offered to her by her mother-in-law on her wedding day. It was advice that she followed assiduously, she said. “Reacting in anger or annoyance will not advance one’s ability to persuade.”

She often moulded her silences into thoughtful pauses. “This can be unnerving, especially at the Supreme Court, where silence only amplifies the sound of ticking clocks,” wrote Jeffrey Toobin, who profiled Ginsburg for the New Yorker in 2013. But her considered interludes likely amplified her voice too.

Ginsburg also understood how to express herself in other ways. In her later years at the Supreme Court she began to accessorize, wearing a golden flower-like crochet collar on days where she would announce a majority view, and a black beaded collar for dissents.

She apologised after criticising Donald Trump in July 2016, saying that as a judge her comments were “ill-advised” and that she would be “more circumspect” in the future. But her decision to wear her so-called “dissenting collar” the day after Trump’s election spoke volumes nonetheless.

Ginsburg’s respectful and dignified expression, her consensus-building approach, and her mission to uphold women’s rights, alongside other fundamental freedoms, made her an antidote to the Trump Era.

At a time when it seems so crucial, Ginsburg inspires us to choose our moment – and our words – carefully, and to stand up for those who need our support. And, when necessary, to fearlessly diverge and wear our dissent with purpose.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Jul 2016 | Americas, mobile, News and features, United States

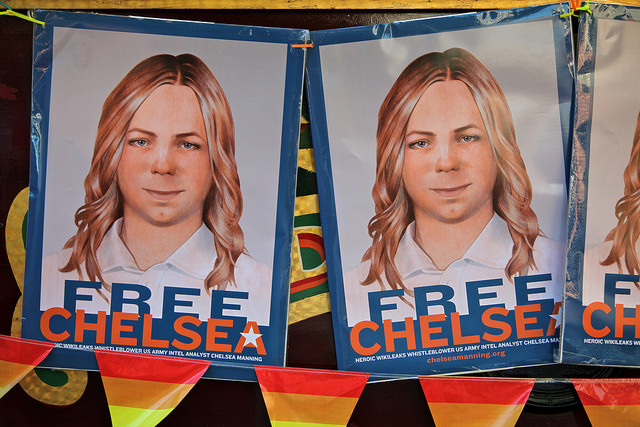

Although the USA is considered to have relatively generous freedoms of speech and the press protected under the First Amendment to the US Constitution, these freedoms have their limits. Many whistleblowers are not afforded protection in the USA and are subjected to lengthy prison terms after disclosing classified information to the public.

Chelsea Manning’s suicide attempt on 5 July, six years into her 35-year sentence, highlights the severity the USA practices when sentencing whistleblowers. Manning was responsible for the leaks of classified US military information to Wikileaks including videos, incident reports from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, information on detainees at Guantanamo and thousands of Department of State cables. She was sentenced on 21 August 2013 to 35 years at the maximum-security US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth.

Manning’s case appears to be the rule, not the exception, in the USA.

Jeffrey Sterling

Considered to be a whistleblower by some, Jeffrey Sterling, who worked for the CIA from 1993 to 2002, was charged under the Espionage Act with mishandling national defense information in 2010. Sterling was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for his contributions to New York Times journalist James Risen’s book, State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration, which detailed the failed CIA Operation Merlin that may have inadvertently aided the Iranian nuclear weapons program. Risen was subpoenaed twice to testify in the case United States v Sterling but refused, resulting in a seven-year legal battle.

On 11 May 2015, at Sterling’s sentencing, judge Leonie Brinkema stated that although she was moved by his professional history, she wanted to send a message to other whistleblowers of the “price to be paid” when revealing government secrets.

Stephen Jin-Woo Kim

Stephen Kim is a former US Department of State contractor who, on 11 June 2009, spoke to Fox News reporter James Rosen about North Korean plans for a nuclear bomb test. Kim allegedly sought Rosen out after becoming frustrated that there was little being done in the Department of State in response to the threats of nuclear tests in North Korea, tests that were ultimately carried out. Fox News published Rosen’s article, North Korea Intends to Match U.N. Resolution With New Nuclear Test, which resulted in an FBI investigation. Kim subsequently pleaded guilty to a single felony count of unauthorised disclosure of national defense information and was sentenced to 13 months in prison on 7 February 2014.

John Kiriakou

John Kiriakou, a former CIA officer, was charged with disclosing information to journalists on several occasions, including revealing the use of torture on Abu Zubaydah and connecting a covert operative to a specific undercover operation. Kiriakou accepted a plea bargain that spared the journalists he had spoken with from having to testify by pleading guilty to one count of violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act.

On 28 February 2013, Kiriakou began serving his 30-month sentence. He has stated that his case was more about punishment for exposing torture than leaking information and that he would “do it all over again”.

Edward Snowden

Although the most famous whistleblower on this list has not been tried and sentenced, Edward Snowden could face up to 30 years in prison for his multiple felony charges under the World War I-era Espionage Act. Snowden was charged on 14 June 2013 for his role in leaking classified information from the National Security Agency, notably a global surveillance initiative.

Snowden has expressed a willingness to go to prison for his actions but refuses to be used as a “deterrent to people trying to do the right thing in difficult situations” as so many whistleblowers often are.

Barrett Brown

The political climate in the US has become so hostile towards leaks that even journalists can face repercussions for their involvement with whistleblowers. American journalist and essayist Barrett Brown’s case became well-known after he was arrested for copying and pasting a hyperlink to millions of leaked emails from Stratfor, an American private intelligence company, from one chat room to another. The leak itself had been orchestrated by Jeremy Hammond, who is serving 10 years in prison for his participation, and did not involve Brown. Brown faced a sentence of up to 102 years in prison, once again for sharing a hyperlink, before the 12 counts of aggravated identity theft and trafficking in stolen data charges were dropped in 2013.

Although the dismissal of these charges was heralded as a victory for press freedom, Brown was still convicted of two counts of being an accessory after the fact and obstructing the execution of a search warrant. On 22 January 2015, Brown was sentenced to 63 months in prison and ordered to pay $890,250 in fines and restitution to Stratfor.