9 Feb 2021 | News and features, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

To:

The Right Honourable William Wragg MP, Chair, Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee

The Right Honourable Julian Knight MP, Chair, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee

CC

The Right Honourable Michael Gove, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office

The Right Honourable Chloe Smith, Minister for the Cabinet Office

Dunja Mijatovic, Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner

Irene Khan, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of freedom of opinion and expression

Elizabeth Denham, UK Information Commissioner

Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon; UK Foreign Office

Kanbar Hossein Bor; UK Foreign Office

We are writing to you to raise serious concerns about the difficulties that journalists, researchers and members of the public currently experience when trying to use FOI legislation, across government.

As you know, the Freedom of Information Act 2000 sets standards for openness and transparency from government, and is a critical tool for ensuring that journalists and members of the public can scrutinise the workings of government.

We have, however, become increasingly concerned about the way in which the legislation is being interpreted and implemented. As the new openDemocracy report ‘Art of Darkness’ makes clear, FOI response rates are at the lowest level since the introduction of the Act 20 years ago.

The report also points to increasing evidence of poor practices across government, such as the use of ‘administrative silence’ to stonewall requests.

In addition, it was recently reported that the Cabinet Office is operating a ‘Clearing House’ unit in which FOI responses are centrally coordinated, undermining the applicant-blind principle of the Act. This raises serious questions about whether information requests by journalists and researchers are being treated and managed differently.

The new report also shows that the regulator charged with implementing Freedom of Information legislation – the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) – has seen its budget cut by 41 per cent over the last decade while its FOI complaint caseload has increased by 46 per cent in the same period.

We believe that there are now strong grounds for a review of the UK government’s treatment of and policies for dealing with Freedom of Information requests, and would urge the minister to address these concerns. We urge you to take the following steps as a matter of priority:

-

Open an inquiry into the operation of the Clearing House, which comprehensively investigates whether its operation is GDPR-compliant, whether journalists and other users of the Act are being monitored and/or blacklisted, and whether this is illegal and/or undermines the applicant-blind principle of the Act.

-

Consider the merits of introducing an ‘administrative silence’ rule whereby a failure to respond to a request within the requisite time period is deemed to be a refusal and can be appealed in full to the ICO.

-

Recognise the national interest of an independent and fully funded regulator of information rights by considering the ICO’s critical lack of funding, and making the regulator accountable to and funded by parliament.

Despite recommendations from the ICO, the government has also declined to expand the FOI Act to cover public contracts to private firms – and has failed to deliver on its own pledges to increase the proactive publication of contracting data.

Given the recent National Audit Office report’s criticism about the lack of transparency in government Covid contracting, it is high time that this recommendation was followed through – and that further measures as outlined above are taken to protect and strengthen the public’s right to access information.

Yours,

Mary Fitzgerald, Editor in Chief, openDemocracy

Katharine Viner, Editor in Chief, The Guardian

John Witherow, Editor, The Times

Emma Tucker, Editor, The Sunday Times

Chris Evans, Editor, The Daily Telegraph

Roula Khalaf, Editor, The Financial Times

Alison Phillips, Editor, Daily Mirror

Paul Dacre, Editor-in-Chief, Associated Newspapers, former Editor, Daily Mail

Alan Rusbridger, former Editor in Chief, The Guardian

Lionel Barber, former Editor, Financial Times

Veronica Wadley, Chair of Arts Council London; former Editor, Evening Standard

David Davis MP

Alex Graham, Chair of the Scott Trust

Ian Murray, Executive Director, Society of Editors

Sir Alan Moses, former Chair, IPSO

Anne Lapping CBE, former Deputy Chair, IPSO

Philip Pullman, author

Baroness Janet Whitaker

Baroness Tessa Blackstone

Ruth Smeeth, Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

Daniel Bruce, Chief Executive, Transparency International

Daniel Gorman, Director, English PEN

Menna Elfyn, President of Wales PEN Cymru

Carl MacDougall, President of Scottish PEN

Rebecca Vincent, Director of International Campaigns, Reporters Without Borders

Michelle Stanistreet, General Secretary, National Union of Journalists

Sian Jones, President, National Union of Journalists

Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive Officer, Internews Europe

John Sauven, Executive Director, Greenpeace

Rachel Oldroyd, Managing Editor, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism

Jonathan Heawood, Public Interest News Foundation

Anthony Barnett, Founding Director, Charter 88

Chris Blackhurst, former Editor, The Independent

Suzanna Taverne, Chair, openDemocracy

Philippe Sands QC

George Peretz QC

David Leigh, investigative journalist

Robert Peston, journalist and author

Peter Oborne, journalist and author

Nick Cohen, journalist and author

David Aaronovitch, journalist and author

Michael Crick, journalist and author

Ian Cobain, investigative journalist

Tom Bower, investigative journalist

Aditya Chakrabortty, Senior Economics Commentator, The Guardian

Jason Beattie, Assistant Editor, the Daily Mirror

Rowland Manthorpe, Technology Correspondent, Sky News

Cynthia O’Murchu, Investigative Reporter, Financial Times

Tom Warren, Investigative Reporter, BuzzFeed News

Christopher Hird, Founder and Managing Director, Dartmouth Films

Meirion Jones, Investigations Editor, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism

James Ball, Global Editor, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism

Oliver Bullough, journalist and author

Henry Porter, journalist and author

Peter Geoghegan, Investigations Editor, openDemocracy

Margot Gibbs, Senior Reporter, Finance Uncovered

Lionel Faull, Chief Reporter, Finance Uncovered

Chris Cook, Contributing editor, Tortoise

Brian Cathcart, Professor of Journalism, Kingston University

Mark Cridge, Chief Executive, mySociety

Dr Susan Hawley, Executive Director, Spotlight on Corruption

Helen Darbishire, Executive Director, Access Info Europe

Miriam Turner and Hugh Knowles, co-CEOs, Friends of the Earth

Mike Davis, Executive Director, Global Witness

Silkie Carlo, Director, Big Brother Watch

Natalie Fenton, Professor of Media and Communications, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dr Lutz Kinkel, the Managing Director of the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

Scott Griffen, Deputy Director of International Press Institute

Granville Williams, Editor, Media North

Alison Moore, journalist and editor

Tim Gopsil, Former Editor, Free Press and the Journalist magazine

Dave West, Deputy Editor, Health Services Journal

Dr Sam Raphael, Director, UK Unredacted and University of Westminster

Leigh Baldwin and Marcus Leroux, SourceMaterial

Vicky Cann, Corporate Europe Observatory

Barnaby Pace, Senior Campaigner, Global Witness

Lisa Clark, Scottish PEN Project Manager

Nick Craven, journalist

Caroline Molloy, Editor, openDemocracy UK

Jenna Corderoy, Investigative Reporter, openDemocracy

Jamie Beagent, Partner, Leigh Day

Sean Humber, Partner, Leigh Day

Harminder Bains, Partner, Leigh Day

Thomas Jervis, Partner, Leigh Day

Oliver Holland, Partner, Leigh Day

Merry Varney, Partner, Leigh Day

Daniel Easton, Partner, Leigh Day

Michael Newman, Partner, Leigh Day

Sarah Campbell, Partner, Leigh Day

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

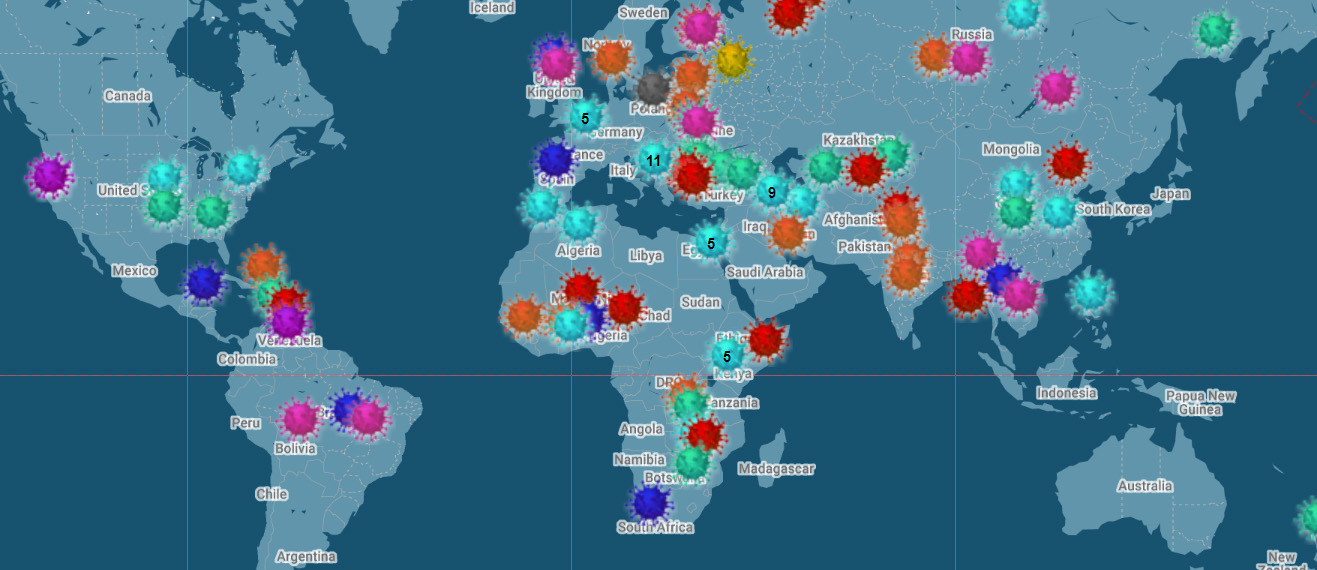

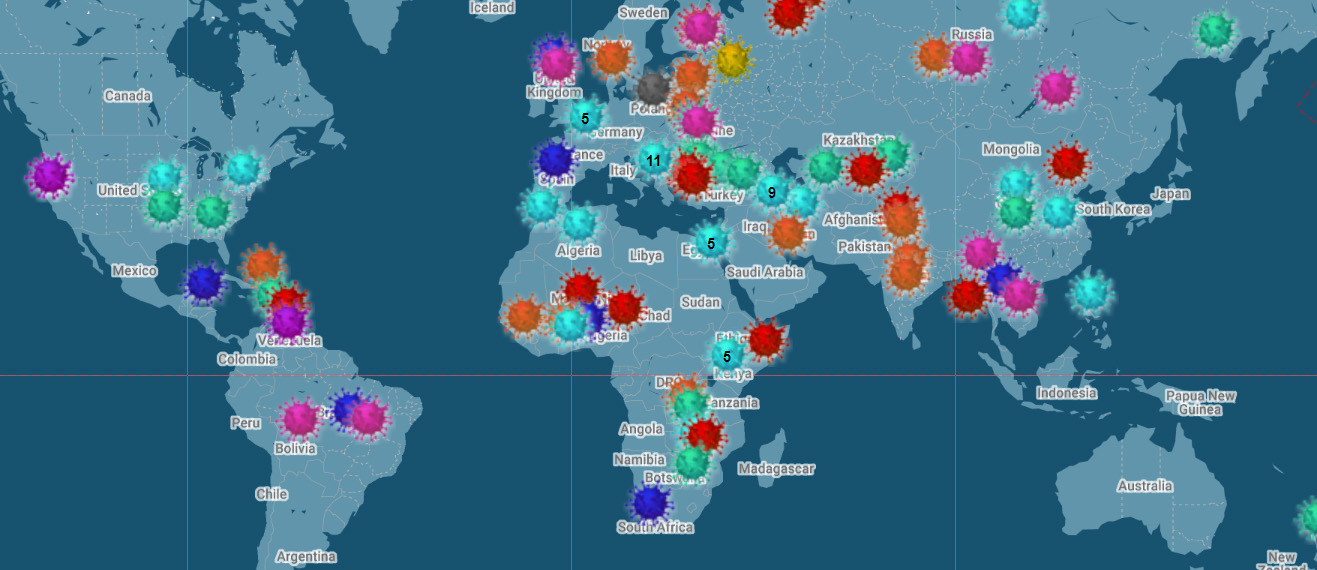

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, mobile, News and features

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, of ruling party Fidesz (Pic © European People’s Party/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

The Hungarian parliament has voted yes to plans to allow the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “human labour costs” of freedom of information (FOI) requests this week, as well as granting sweeping new powers to withhold information. It just needs the signature of President Janos Ader before it becomes law.

The bill, submitted by Minister of Justice László Trócsányi, was published on the government website just days before the vote, on 3 July, precluding any meaningful debate about the proposal. It is widely believed that through this initiative, governing party Fidesz is trying to put a lid on a number of scandals involving wasteful government spending, uncovered through FOI requests.

According to Transparency International, the bill “appears to be a misguided response by the Hungarian government to civil society’s earlier successful use of freedom of information tools to publicly expose government malpractice and questionable public spending”.

One provision of the bill allows public bodies to refuse to make certain data public for 10 years if deemed to have been used in decision-making processes, according to Index award-winning Hungarian investigative news platform Atlatszo.hu. As virtually any piece of information can be used to build public policies upon, this gives the government a powerful argument not to answer FOI requests.

The bill also allows government actors to charge fees for fulfilling FOI request. Until now, government actors could ask for the copying expenses of documents. From now on, they can ask the person filing the request to cover the “human labor costs” of the inquiry.

It is not yet clear how much members of the public will have to pay. “There will be a separate government decree in the future regarding the costs that can be charged for a FOI request,” Tibor Sepsi, a lawyer working for Atlatszo.hu, says.

Because the public has no means to verify whether these costs are well-grounded, and at some government agencies the salaries are known to be very high, the government might be in a discretionary position to ask prohibitive costs for answering the FOI requests, critics of the amendment say.

“The FOI requests usually ask for data that are already available somewhere in electronic format, therefore no government body can say that fulfilling a request involves gathering information,” says Tamás Bodoky, the editor-in-chief of Atlatszo.hu.

“It is unacceptable to plead for extraordinary workload and expenses when much of the requests refer to things that should be published in accordance with transparent pocket rules. This information should be readily available in the settlement of accounts and reports,” he adds.

The work of investigative journalists and watchdog NGOs is further complicated through another provision, regarding copyright. In some cases, the government will be able to refer to copyright issues and only give limited access to certain documents, without making them publicly available.

While the bill will make life harder for those making FOI requests, Sepsi also points out that the situation is not as bad as it may initially seem: “The government will have half a dozen of new ways to reject vexatious FOI requests, but on the implementation level, ordinary courts, the constitutional court or the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority will have the power to keep things under reasonable control.”

Nevertheless, Hungarian and international NGOs working for the transparency of public spending and government decisions are protesting against the bill. An open letter, signed by the groups Atlatszo.hu, K-Monitor, Energiaklub Szakpolitikai Intézet and Transparency International Magyarország Alapítvány has been sent to the Minister of Justice Trócsányi, to the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority, as well as the MPs whose votes decided the fate of the proposal.

“We believe the government would do the right thing if – instead of rolling back on transparency – it would increase the so-called proactive disclosure, meaning that it would publish the information regarding its functioning in electronic format, without a request. We can provide international examples where this can be achieved simply, without extraordinary costs. This would increase not only the transparency of public spending, but the number of FOI requests would also decrease significantly,” the letter argues.

After the vote, a group of 50 opposition MPs pledged to ask the constitutional court to review the text.

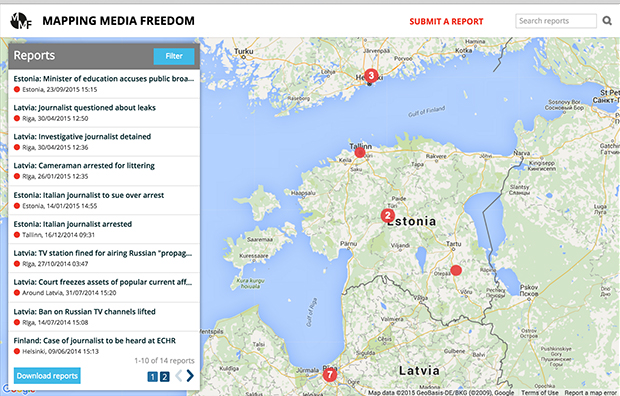

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted on 6 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org